Posts Tagged Bayes Theorem

Rational Atrocity?

Posted by Bill Storage in Probability and Risk on July 4, 2025

Bayesian Risk and the Internment of Japanese Americans

We can use Bayes (see previous post) to model the US government’s decision to incarcerate Japanese Americans, 80,000 of which were US citizens, to reduce a perceived security risk. We can then use a quantified risk model to evaluate the internment decision.

We define two primary hypotheses regarding the loyalty of Japanese Americans:

- H1: The population of Japanese Americans are generally loyal to the United States and collectively pose no significant security threat.

- H2: The population of Japanese Americans poses a significant security threat (e.g., potential for espionage or sabotage).

The decision to incarceration Japanese Americans reflects policymakers’ belief in H2 over H1, updated based on evidence like the Niihau Incident.

Prior Probabilities

Before the Niihau Incident, policymakers’ priors were influenced by several factors:

- Historical Context: Anti-Asian sentiment on the West Coast, including the 1907 Gentlemen’s Agreement and 1924 Immigration Act, fostered distrust of Japanese Americans.

- Pearl Harbor: The surprise attack on December 7, 1941, heightened fears of internal threats. No prior evidence of disloyalty existed.

- Lack of Data: No acts of sabotage or espionage by Japanese Americans had been documented before Niihau. Espionage detection and surveillance were limited. Several espionage rings tied to Japanese nationals were active (Itaru Tachibana, Takeo Yoshikawa).

Given this, we can estimate subjective priors:

- P(H1) = 0.99: Policymakers might have initially been 99 percent confident that Japanese Americans were loyal, as they were U.S. citizens or long-term residents with no prior evidence of disloyalty. The pre-Pearl Harbor Munson Report (“There is no Japanese `problem’ on the Coast”) supported this belief.

- P(H2) = 0.01: A minority probability of threat due to racial prejudices, fear of “fifth column” activities, and Japan’s aggression.

These priors are subjective and reflect the mix of rational assessment and bias prevalent at the time. Bayesian reasoning (Subjective Bayes) requires such subjective starting points, which are sometimes critical to the outcome.

Evidence and Likelihoods

The key evidence influencing the internment decision was the Niihau Incident (E1) modeled in my previous post. We focus on this, as it was explicitly cited in justifying internment, though other factors (e.g., other Pearl Harbor details, intelligence reports) played a role.

E1: The Niihau Incident

Yoshio and Irene Harada, Nisei residents, aided Nishikaichi in attempting to destroy his plane, burn papers, and take hostages. This was interpreted by some (e.g., Lt. C.B. Baldwin in a Navy report) as evidence that Japanese Americans might side with Japan in a crisis.

Likelihoods:

P(E1|H1) = 0.01: If Japanese Americans are generally loyal, the likelihood of two individuals aiding an enemy pilot is low. The Haradas’ actions could be seen as an outlier, driven by personal or situational factors (e.g., coercion, cultural affinity). Note that this 1% probability is not the same 1% probability of H1, the prior belief that Japanese Americans weren’t loyal. Instead, P(E1|H1) is the likelihood assigned to whether E1, the Harada event, would have occurred given than Japanese Americans were loyal to the US.

P(E1|H2) = 0.6: High likelihood of observing the Harada evidence if the population of Japanese Americans posed a threat.

Posterior Calculation Using Bayes Theorem:

P(H1∣E1) = P(E1∣H1)⋅P(H1) / [P(E1∣H1)⋅P(H1)+P(E1∣H2)⋅P(H2)]

P(H1∣E1)=0.01⋅0.99 / [(0.01⋅0.99)+(0.6⋅0.01)] = 0.626

P(H2|E1) = 1 – P(H1|E1) = 0.374

The Niihau Incident significantly increases the probability of H2 (its prior was 0.01), suggesting a high perceived threat. This aligns with the heightened alarm in military and government circles post-Niihau. 62.6% confidence in loyalty is unacceptable by any standards. We should experiment with different priors.

Uncertainty Quantification

- Aleatoric Uncertainty: The Niihau Incident involved only two people.

- Epistemic Uncertainty: Prejudices and wartime fear would amplify P(H2).

Sensitivity to P(H1)

The posterior probability of H2 is highly sensitive to changes in P(H2) – and to P(H1) because they are linearly related: P(H2) = 1.0 – P(H1).

The posterior probability of H2 is somewhat sensitive to the likelihood assigned to P(E1|H1), but in a way that may be counterintuitive – because it is the likelihood assigned to whether E1, the Harada event, would have occurred given than Japanese Americans were loyal. We now know them to have been loyal, but that knowledge can’t be used in this analysis. Increasing this value lowers the posterior probability.

The posterior probability of H2 is relatively insensitive to changes in P(E1|H2), the likelihood of observing the evidence if Japanese Americans posed a threat (which, again, we now know them to have not).

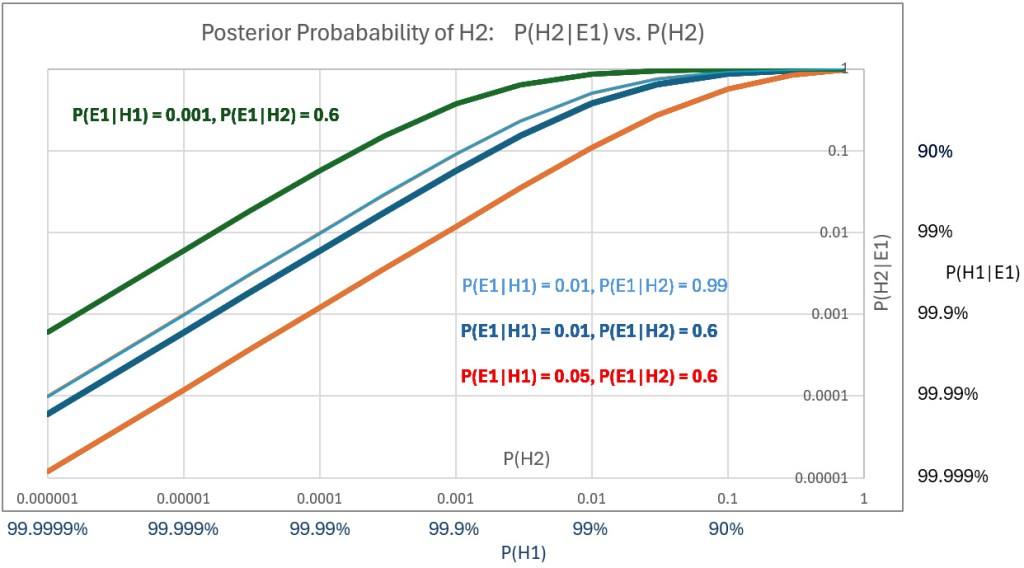

A plot of posterior probability of H2 against the prior probabilities assigned to H2 – that is, P(H2|E1) vs P(H2) – for a range of values of P(H2) using three different values of P(E1|H1) shows the sensitivities. The below plot (scales are log-log) also shows the effect of varying P(E1|H2); compare the thin blue line to the thick blue line.

Prior hypotheses with probabilities greater the 99% represent confidence levels that are rarely justified. Nevertheless, we plot high posteriors for priors of H1 (i.e., posteriors of H2 down to 0.00001 (1E-5). Using P(E1|H1) = 0.05 and P(E1|H2 = 0.6, we get a posterior P(H2|E1) = 0.0001 – or P(H1|E1) = 99.99%, which might be initially judged as not supporting incarceration of US citizens in what were effectively concentration camps.

Risk

While there is no evidence of either explicit Bayesian reasoning or risk quantification by Franklin D. Roosevelt or military analysts, we can examine their decisions using reasonable ranges of numerical values that would have been used if numerical analysis had been employed.

We can model risk, as is common in military analysis, by defining it as the product of severity and probability – probability equal to that calculated as the posterior probability that a threat existed in the population of 120,000 who were interned.

Having established a range of probabilities for threat events above, we can now estimate severity – the cost of a loss – based on lost lives and lost defense capability resulting from a threat brought to life.

The Pearl Harbor attack itself tells us what a potential hazard might look like. Eight U.S. Navy battleships were at Pearl Harbor: Arizona, Oklahoma, West Virginia, California, Nevada, Tennessee, Maryland, and Pennsylvania. Typical peacetime crew sizes ranged from 1,200 to 1,500 per battleship, though wartime complements could exceed that. About 8,000–10,000 sailors were assigned to the battleships. More sailors would have been on board had the attack not happened on a Sunday morning.

About 37,000 Navy and 14,000 Army personnel were stationed at Pearl Harbor. 2,403 were killed in the attack, most of them aboard battleships. Four battleships were sunk. The Arizona suffered a catastrophic magazine explosion from a direct bomb hit. Over 1,170 crew members were killed. 400 were killed on the Oklahoma when it sank. None of the three aircraft carriers of the Pacific Fleet were in Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7. The USS Enterprise was due to be in port on Dec. 6 but was delayed by weather. Its crew was about 2,300 men.

Had circumstances differed slightly, the attack would not have been a surprise, and casualties would have been fewer. But in other conceivable turns of events, they could have been far greater. A modern impact analysis of an attack on Pearl Harbor or other bases would consider an invasion’s “cost” to be 10 to 20,000 lives and the loss of defense capability due to destroyed ships and aircraft. Better weather could have meant destruction of one third of US aircraft carriers in the Pacific.

Using a linear risk model, an analyst, if such analysis was done back then, might have used the above calculated P(H2|E1) as the probability of loss and 10,000 lives as one cost of the espionage. Using probability P(H1) in the range of 99.99% confidence in loyalty – i.e., P(H2) = 1E-4 – and severity = 10,000 lives yields quantified risk.

As a 1941 risk analyst, you would be considering a one-in-10,000 chance of losing 10,000 lives and loss of maybe 25% of US defense capacity. Another view of the risk would be that each of 120,000 Japanese Americans poses a one-in-10,000 chance of causing 10,000 deaths, an expected cost of roughly 120,000 lives (roughly, because the math isn’t quite as direct as it looks in this example).

While I’ve modeled the decision using a linear expected value approach, it’s important to note that real-world policy, especially in safety-critical domains, is rarely risk-neutral. For instance, Federal Aviation Regulation AC 25.1309 states that “no single failure, regardless of probability, shall result in a catastrophic condition”, a clear example of a threshold risk model overriding probabilistic reasoning. In national defense or public safety, similar thinking applies. A leader might deem a one-in-10,000 chance of catastrophic loss (say, 10,000 deaths and 25% loss of Pacific Fleet capability) intolerable, even if the expected value (loss) were only one life. This is not strictly about math; it reflects public psychology and political reality. A risk-averse or ambiguity-intolerant government could rationally act under such assumptions.

Would you take that risk, or would you incarcerate? Would your answer change if you used P(H1) = 99.999 percent? Could a prior of that magnitude ever be justified?

From the perspective of quantified risk analysis (as laid out in documents like FAR AC 25.1309), President Roosevelt, acting in early 1942 would have been justified even if P(H1) had been 99.999%.

In a society so loudly committed to consequentialist reasoning, this choice ought to seem defensible. That it doesn’t may reveal more about our moral bookkeeping than about Roosevelt’s logic. Racism existed in California in 1941, but it unlikely increased scrutiny by spy watchers. The fact that prejudice existed does not bear on the decision, because the prejudice did not motivate any action that would have born – beyond the Munson Report – on the prior probabilities used. That the Japanese Americans were held far too long is irrelevant to Roosevelt’s decision.

Since the rationality of Roosevelt’s decision, as modeled by Bayesian reasoning and quantified risk, ultimately hinges on P(H1), and since H1’s primary input was the Munson Report, we might scrutinize the way the Munson Report informs H1.

The Munson Report is often summarized with its most quoted line: “There is no Japanese ‘problem’ on the Coast.” And that was indeed its primary conclusion. Munson found Japanese American citizens broadly loyal and recommended against mass incarceration. However, if we assume the report to be wholly credible – our only source of empirical grounding at the time – then certain passages remain relevant for establishing a prior. Munson warned of possible sabotage by Japanese nationals and acknowledged the existence of a few “fanatical” individuals willing to act violently on Japan’s behalf. He recommended federal control over Japanese-owned property and proposed using loyal Nisei to monitor potentially disloyal relatives. These were not the report’s focus, but they were part of it. Critics often accuse John Franklin Carter of distorting Munson’s message when advising Roosevelt. Carter’s motives are beside the point. Whether his selective quotations were the product of prejudice or caution, the statements he cited were in the report. Even if we accept Munson’s assessment in full – affirming the loyalty of Japanese American citizens and acknowledging only rare threats – the two qualifiers Carter cited are enough to undercut extreme confidence. In modern Bayesian practice, priors above 99.999% are virtually unheard of, even in high-certainty domains like particle physics and medical diagnostics. From a decision-theoretic standpoint, Munson’s own language renders such priors unjustifiable. With confidence lower than that, Roosevelt made the rational decision – clear in its logic, devastating in its consequences.

Bayes Theorem, Pearl Harbor, and the Niihau Incident

Posted by Bill Storage in Probability and Risk on July 2, 2025

The Niihau Incident of December 7–13, 1941 provides a good case study for applying Bayesian reasoning to historical events, particularly in assessing decision-making under uncertainty. Bayesian reasoning involves updating probabilities based on new evidence, using Bayes’ theorem: P(A∣B) = P(B∣A) ⋅ P(A)P(B) / P(A|B), where:

- P(E∣H) is the likelihood of observing E given H

- P(H∣E) is the posterior probability of hypothesis H given evidence E

- P(H) is the prior probability of H

- P(E) is the marginal probability of E.

Terms like P(E∣H), the probability of evidence given a hypothesis, can be confusing. Alternative phrasings may help:

- The probability of observing evidence E if hypothesis H were true

- The likelihood of E given H

- The conditional probability of E under H

These variations clarify that we’re assessing how likely the evidence is under a specific scenario, not the probability of the hypothesis itself, which is P(H∣E).

In the context of the Niihau Incident, we can use Bayesian reasoning to analyze the decisions made by the island’s residents, particularly the Native Hawaiians and the Harada family, in response to the crash-landing of Japanese pilot Shigenori Nishikaichi. Below, I’ll break down the analysis, focusing on key decisions and quantifying probabilities while acknowledging the limitations of historical data.

Context of the Niihau Incident

On December 7, 1941, after participating in the Pearl Harbor attack, Japanese pilot Shigenori Nishikaichi crash-landed his damaged A6M2 Zero aircraft on Niihau, a privately owned Hawaiian island with a population of 136, mostly Native Hawaiians. The Japanese Navy had mistakenly designated Niihau as an uninhabited island for emergency landings, expecting pilots to await rescue there. The residents, unaware of the Pearl Harbor attack, initially treated Nishikaichi as a guest but confiscating his weapons. Over the next few days, tensions escalated as Nishikaichi, with the help of Yoshio Harada and his wife Irene, attempted to destroy his plane and papers, took hostages, and engaged in violence. The incident culminated in the Kanaheles, a Hawaiian couple, overpowering and killing Nishikaichi. Yoshio Harada committing suicide.

From a Bayesian perspective, we can analyze the residents updating their beliefs as new evidence emerged.

We define two primary hypotheses regarding Nishikaichi’s intentions:

- H1: Nishikaichi is a neutral (non-threatening) lost pilot needing assistance.

- H2: Nishikaichi is an enemy combatant with hostile intentions.

The residents’ decisions reflect the updating of beliefs about (credence in) these hypotheses.

Prior Probabilities

At the outset, the residents had no knowledge of the Pearl Harbor attack. Thus, their prior probability for P(H1) (Nishikaichi is non-threatening) would likely be high, as a crash-landed pilot could reasonably be seen as a distressed individual. Conversely, P(H2) (Nishikaichi is a threat) would be low due to the lack of context about the war.

We can assign initial priors based on this context:

- P(H1) = 0.9: The residents initially assume Nishikaichi is a non-threatening guest, given their cultural emphasis on hospitality and lack of information about the attack.

- P(H2) = 0.1: The possibility of hostility exists but is less likely without evidence of war.

These priors are subjective, reflecting the residents’ initial state of knowledge, consistent with the Bayesian interpretation of probability as a degree of belief.

We identify key pieces of evidence that influenced the residents’ beliefs:

E1: Nishikaichi’s Crash-Landing and Initial Behavior

Nishikaichi crash-landed in a field near Hawila Kaleohano, who disarmed him and treated him as a guest. His initial behavior (not hostile) supports H1.

Likelihoods:

- P(E1∣H1) = 0.95: A non-threatening pilot is highly likely to crash-land and appear cooperative.

- P(E1∣H2) = 0.3: A hostile pilot could be expected to act more aggressively, though deception is possible.

Posterior Calculation:

P(H1∣E1) = [P(E1∣H1)⋅P(H1)] / [P(E1∣H1)⋅P(H1) + P(E1∣H2)⋅P(H2) ]

P(H1|E1) = 0.95⋅0.9 / [(0.95⋅0.9) + (0.3⋅0.1)] = 0.97

After the crash, the residents’ belief in H1 justifies hospitality.

E2: News of the Pearl Harbor Attack

That night, the residents learned of the Pearl Harbor attack via radio, revealing Japan’s aggression. This significantly increases the likelihood that Nishikaichi was a threat.

Likelihoods:

- P(E2∣H1) = 0.1 P(E2|H1) = 0.1 P(E2∣H1) = 0.1: A non-threatening pilot is unlikely to be associated with a surprise attack.

- P(E2∣H2) = 0.9 P(E2|H2) = 0.9 P(E2∣H2) = 0.9: A hostile pilot is highly likely to be linked to the attack.

Posterior Calculation (using updated priors from E1):

P(H1∣E2) = P(E2∣H1)⋅P(H1∣E1) / [P(E2∣H1)⋅P(H1∣E1) + P(E2∣H2)⋅P(H2∣E1)]

P(H1∣E2) = 0.1⋅0.97 / [(0.1⋅0.97) + (0.9⋅0.03)] = 0.76

P(H2∣E2) = 0.24

The news shifts the probability toward H2, prompting the residents to apprehend Nishikaichi and put him under guard with the Haradas.

E3: Nishikaichi’s Collusion with the Haradas

Nishikaichi convinced Yoshio and Irene Harada to help him escape, destroy his plane, and burn Kaleohano’s house to eliminate his papers.

Likelihoods:

- P(E3∣H1) = 0.01: A non-threatening pilot is extremely unlikely to do this.

- P(E3∣H2) = 0.95: A hostile pilot is likely to attempt to destroy evidence and escape.

Posterior Calculation (using updated priors from E2):

P(H1∣E3) = P(E3∣H1)⋅P(H1∣E2) / [P(E3∣H1)⋅P(H1∣E2) + P(E3∣H2)⋅P(H2∣E2)]

P(H1∣E3) = 0.01⋅0.759 / [(0.01⋅0.759) + (0.95⋅0.241)] = 0.032

P(H2∣E3) = 0.968

This evidence dramatically increases the probability of H2, aligning with the residents’ decision to confront Nishikaichi.

E4: Nishikaichi Takes Hostages and Engages in Violence

Nishikaichi and Harada took Ben and Ella Kanahele hostage, and Nishikaichi fired a machine gun. Hostile intent is confirmed.

Likelihoods:

- P(E4∣H1) = 0.001: A non-threatening pilot is virtually certain not to take hostages or use weapons.

- P(E4∣H2) = 0.99: A hostile pilot is extremely likely to resort to violence.

Posterior Calculation (using updated priors from E3):

P(H1∣E4) = P(E4∣H1)⋅P(H1∣E3)/ [P(E4∣H1)⋅P(H1∣E3) + P(E4∣H2)⋅P(H2∣E3)P(H1|E4)]

P(H1∣E4) = 0.001⋅0.032 / [(0.001⋅0.032)+(0.99⋅0.968)] =0.00003

P(H2∣E4) = 1.0 – P(H1∣E4) = 0.99997

At this point, the residents’ belief in H2 is near certainty, justifying the Kanaheles’ decisive action to overpower Nishikaichi.

Uncertainty Quantification

Bayesian reasoning also involves quantifying uncertainty, particularly aleatoric (inherent randomness) and epistemic (model uncertainty) components.

Aleatoric Uncertainty: The randomness in Nishikaichi’s actions (e.g., whether he would escalate to violence) was initially high due to the residents’ lack of context. As evidence accumulated, this uncertainty decreased, as seen in the near-certain posterior for H2 after E4.

Epistemic Uncertainty: The residents’ model of Nishikaichi’s intentions was initially flawed due to their isolation and lack of knowledge about the war. This uncertainty reduced as they incorporated news of Pearl Harbor and observed Nishikaichi’s actions, refining their model of his behavior.

Analysis of Decision-Making

The residents’ actions align with Bayesian updating:

Initial Hospitality (E1): High prior for H1 led to treating Nishikaichi as a guest, with precautions (disarming him) reflecting slight uncertainty.

Apprehension (E2): News of Pearl Harbor shifted probabilities toward H2, prompting guards and confinement with the Haradas.

Confrontations (E3, E4): Nishikaichi’s hostile actions (collusion, hostage-taking) pushed P(H2) to near 1, leading to the Kanaheles’ lethal response.

The Haradas’ decision to assist Nishikaichi complicates the analysis. Their priors may have been influenced by cultural or personal ties to Japan, increasing their P(H1) or introducing a separate hypothesis of loyalty to Japan. Lack of detailed psychological data makes quantifying their reasoning speculative.

Limitations and Assumptions

Subjective Priors: The assigned priors (e.g., P(H1) = 0.9) are estimates based on historical context, not precise measurements. Bayesian reasoning allows subjective priors, but different assumptions could alter results.

Likelihood Estimates: Likelihoods (e.g., P(E1∣H1) = 0.95) are informed guesses, as historical records lack data on residents’ perceptions.

Simplified Hypotheses: I used two hypotheses for simplicity. In reality, residents may have considered nuanced possibilities, e.g., Nishikaichi being coerced or acting out of desperation.

Historical Bias: may exaggerate or omit details, affecting our understanding of evidence.

Conclusion

Bayesian reasoning (Subjective Bayes) provides a structured framework to understand how Niihau’s residents updated their beliefs about Nishikaichi’s intentions. Initially, a high prior for him being non-threatening (P(H1)=0.9) was reasonable given their isolation. As evidence accumulated (news of Pearl Harbor, Nishikaichi’s collusion with the Haradas, and his violent actions) the posterior probability of hostility, P(H2) approached certainty, justifying their escalating responses. Quantifying this process highlights the rationality of their decisions under uncertainty, despite limited information. This analysis demonstrates Bayesian inference used to model historical decision-making, assuming the deciders were rational agents.

Next

The Niihau Incident influenced U.S. policy decisions regarding the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. It heightened fears of disloyalty among Japanese Americans. Applying Bayesian reasoning to the decision to intern Japanese Americans after the Niihau Incident might provide insight on how policymakers updated their beliefs about the potential threat posed by this population based on limited evidence and priors. In a future post, I’ll use Bayes’ theorem to model this decision-making process to model the quantification of risk.

Recent Comments