Crystals Know What Day It Is

Posted by Bill Storage in Commentary, Engineering & Applied Physics on January 9, 2026

Shelley, raising an eyebrow, asked me if I knew anything about energy. She was our departmental secretary at Boeing. I pictured turbomachinery, ablative dissipation, and aircraft landings. Yes, I said, some aspects. She handed me a pamphlet from Adam, an engineer in Propulsion. He was moonlighting as an energy consultant. That’s what the cover said. California law was clear. Boeing couldn’t stop him from doing whatever he wanted on his own time.

The pamphlet explained how energy flowed between people and from crystals to people, but only natural crystals. I flipped a few pages. You could convert a man-made crystal to a natural one by storing it under a pyramid for 30 days. Thirty. Giza pyramids? Or would cardboard do? Would crystals know about days? Would they choose a number tied to the sun? Twelve months in a year. Or the moon? Or a number that changed over geologic time? A billion years ago, when days were 18 hours long, did man-made crystals take 40 days to cure?

Shelley asked what I thought. I said I thought he wanted in her pants. He was an engineer, trained in physics and reasoning. He worked with wind tunnels. Adam knows better and thinks you don’t, I said. Shelley shook her head. She knew I was being charitable. Adam believed that stuff.

On a ski trip with Garrett Turbine employees, Melissa insisted we heat water on the stove. Microwave ovens, she said, rearranged the molecular structure of water. Unsafe. Melissa designs auxiliary power units for jets.

They’re not dumb. They can engineer turbomachinery that doesn’t end in a water landing. People rarely run a single epistemic operating system. Rules are brutal in the wind tunnel. Models either converge or they don’t. Reality testifies. In the personal realm, reality can be more forgiving. You can hold nonsense for decades without a compressor stall.

Some of it looks like motivated belief. Whatever his intentions toward Shelley, something about identity and control was at work. Crystals cast him as holding esoteric knowledge. The thinking followed the role.

Engineers also learn to trust models. That works when physics pushes back. Less so when nothing ever does.

Success doesn’t help. The GE90 turbine’s in-flight shutdown rate is about one per million flight hours on the triple seven. Do that well for long enough and humility thins. An ER doc once told me surgeons are often right and never uncertain. Trained for one, rewarded for the other.

Some ideas live where no one checks them. There’s no Flight Readiness Review for microwave theories. No stress test. The questions about days and crystals never get asked.

What, then, do microwaves do to water? Start with the physics. Microwave ovens radiate photons that excite rotational modes in polar molecules like water. For quantum reasons, the hydrogen atoms aren’t evenly spaced but sit to one side, like Mickey Mouse ears. The molecule is electrically neutral, but its charge is uneven. That polarity makes water responsive to oscillating electric fields.

Melissa translated water’s dipole moment into “warped molecules.” What actually happens is boring. The hydrogen-bond network jiggles, breaks, reforms, then settles back into the same statistical distribution. Heat water on a stove and it happens even more. Ice made from microwaved water freezes normally. Enzymes and bacteria, testifying by the trillions, vote not guilty.

“Excite” and “rotational modes” sound like structural meddling if you distrust boxes that hum. Adam and Melissa use the right nouns, invoke real properties, and gesture at invisible mechanisms. Heat from a flame feels natural; the word “radiate” smuggles in nuclear anxiety.

Crystal mysticism has roots in real science. Mid-century physics pulled quartz oscillators, piezoelectricity, band gaps, and lasers out of its hat. Crystals turn pressure into voltage, voltage into timekeeping, and sand into computation. LCDs followed: apply a voltage, patterns appear. In that sense, crystals do know time. Order responds to invisible forces. Once imagined as intentional, it drifts right on down, lands in nonsense.

The 30-day pyramid transformation launders mysticism through quasi-engineering constraints. Not “chant until Houtu signals,” but “store for 30 days.” A soak time defined in a spec. It feels procedural rather than occult. When Adam’s unwired crystals track solar days, not sidereal time, the scaffolding shows through.

Asking how Adam’s crystals know what a day is would mean letting astronomy into his pyramid. No one in the kitchen with Melissa demands control samples. The beliefs survive by staying small, domestic, and unreviewed. Engineers are trained to respect reality where reality speaks loud. Elsewhere, we’re free to improvise. The danger is not believing nonsense. It’s knowing the questions that would shatter the spell. And doing nothing.

Don’t Skimp on Shoes

Posted by Bill Storage in Commentary on January 2, 2026

When I was a kid, mom and dad went out for the evening and told me that Frank, whom I hadn’t met, was going to stop by. He was dropping off some coins from his collection. He wanted us to determine whether these gold coins were legitimate, ninety percent gold, “.900 fineness,” as specified by the Coinage Act of 1837.

After the 1974 legalization of private gold ownership in the U.S., demand surged for pre-1933 American gold coins as bullion investments rather than numismatic curiosities. The market became jumpy, especially among buyers who cared only about intrinsic value. Counterfeit U.S. gold coins did exist. They were high-quality struck fakes, not crude castings, and they were made from real ninety percent gold alloy. Counterfeiters melted down common-date coins to produce rarer ones. Gold-plated base-metal fakes also existed, but those were cast, and Frank would never have fallen for them. We know that now. At the time, reliable information was thin on the ground.

The plan was to use Archimedes’ method. We’d weigh the coins, then dunk them in water and measure the displacement. Weight divided by displaced volume gives density. Ninety percent gold with ten percent copper comes out to 17.15 grams per cubic centimeter. Anything lower meant trouble.

The doorbell rang. Frank was a big guy in flannel shirt and jeans. He said he had something for my dad. I told him dad said he’d be coming. Frank handed me a small bag weighing five pounds – avoirdupois, not troy. About fifteen thousand dollars’ worth of gold at the time. You could buy a Corvette coupe, not the cheaper convertible, for six thousand. He handed me the bag, said thanks, and drove off in his pickup truck.

A few years ago I went on a caving trip to the Marble Mountains of northern California. The walk in didn’t look bad on paper. Five or six miles, maybe a couple thousand feet of elevation gain. With camping gear, food, and a load of heavy caving equipment, it turned out to be very bad indeed. I underestimated it, and paid for it.

A month before I’d been in Hawaii hiking to and through lava tubes in a recent flow, not the friendly pahoehoe kind but the boot-shredding a‘a stuff. A few days there destroyed a decent pair of boots. Desperate to make a big connection between two distant entrances, Doug drove me to Walmart, and I bought one of their industrial utility specials. It would get me through the day. It did. Our lava tube was four miles end to end.

I forgot about my boot situation until the Marble Mountains trip. At camp, as I was cutting sheets of moleskin to armor my feet for the hike out, I met a caver who knew my name and treated me as someone seasoned, someone who ought to know better. He looked down at my feet, laughed, and said, “Storage, you of all people, I figured wouldn’t wear cheap shoes into the mountains.” He figured wrong. I wore La Sportivas on the next trip.

What struck me as odd, I told my dad when he got home, wasn’t that Frank trusted a kid with fifteen thousand dollars in gold. It was that he drove a beat-up truck. I mentioned the rust.

“Yeah,” dad said. “But it’s got new tires.”

Dugga Dugga Dugga

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Art, speleology on December 30, 2025

This story is about the band Wire and about using electric hammer drills in caves. That’s why I called this site The Multidisciplinarian. Not because I’m competent in many disciplines, or because I harbor disciplinarians in the basement, but because I wanted a single conversational space where unrelated things could bump into each other and see what happens. That’s what early bloggers did. Not Jorn Barger in 1997, when he coined the hideous word “blogging.” I’m still recovering. I mean the nineteenth-century social diarists. People made public diaries: Here’s my thoughts, see what you think. Beatrice Webb, aptly named, ran what was essentially a Victorian blog when she wasn’t co-founding the London School of Economics. If this social diary bores you, skip to the end and watch the 3-minute video.

I used to write record reviews for a couple of magazines. I was bad at it. I quit in frustration after reading what struck me as a devastatingly concise review of a Pere Ubu album. Pere Ubu, for the uninitiated, was an avant-garage band from northern Ohio who were far more popular on other continents than in Cleveland. Or even trendy Kent, Ohio.

The reviewer wrote something like this:

David Thomas, Ubu’s singer, though many people disputed that what he did qualified as singing, is coming from wherever Jim Morrison was heading. Pere Ubu is what Roxy Music would have been if Eno had taken over, fired Bryan Ferry, and hired a neurotic poet.

David Thomas, incidentally, later used several of my photos. Twenty years on, he told me he was thrilled that I’d captured what appear to be the only known photos of classic-era Pere Ubu, the brief and unrepeatable moment when Mayo Thompson and Richard Thompson, from opposite ends of the musical universe, were both in the band. Here’s two I took at the Cleveland Agora, after Thomas told security to let me in with a telephoto.

I remember thinking I could never write a review that clever. The writer, maybe Dean Suzuki, now a music professor at San Francisco State, nailed it. These days, the review impresses me slightly less. The Morrison line doesn’t really explain anything beyond “Thomas is weirder than Morrison.” You might infer that Morrison was a rock singer drifting toward the avant-garde, while Thomas was an avant-garde noise artist drifting toward rock. That’s clever, but it wouldn’t have helped me decide whether to buy The Art of Walking.

The Roxy Music comparison works better. Pere Ubu, like Roxy, made songs. They both layered noise and oddity onto them. But the key difference, the reason the “neurotic poet” line lands, is Thomas’s vocal delivery. He’s been described as yelping, barking, warbling like a distressed whale, or like a nervous art-school guy about to puke or cry. It’s stream-of-consciousness paranoia set to rhythm inside a foundry.

For readers already familiar with early Roxy Music (I discussed here), the analogy signals freaky, Eno-era art rock taken to an extreme, minus the glamour. That might hook you. But it works better as enticement than guidance. As criticism, it dodges the two questions I was supposed to answer. Was the band’s objective worth pursuing? And did they succeed?

Anyway, this piece isn’t about Pere Ubu or The Art of Walking. It’s about Wire and the art of cave exploration. The Pere Ubu detour is just throat-clearing. Amy, a caving friend, once said of my music criticism, “Once a critic, always an ass.” Fair enough.

Wire formed in London in October 1976. The members met at art school and had little prior band experience or instrumental proficiency. They were beginners leaning hard into punk’s DIY ethos. Unlike many of their contemporaries, who pursued deconstruction, Wire practiced pure reductionism. Not the Sex Pistols’ kind. Something colder and more deliberate.

From the start, their influences were eclectic: 60s pop, early Pink Floyd, Roxy Music, Brian Eno, krautrock, and punk, selectively. The Ramones for brevity, not for attitude. Wire always had internal tension between a pop impulse and an experimental or noise impulse. As Colin Newman put it, “Wire’s never really shared much taste as a band. It’s about the work. It always has been.” The tension proved unsustainable. They split in 1979.

So when Wire reappeared in 1986, touring with no advance press, it was a shock. They played none of their early material. Old Wire songs were two-minute punk bursts for intellectuals. New Wire played twenty- to thirty-minute trance pieces. What began as a rehearsal exercise became their most durable experiment. There are now roughly a hundred versions of “The Drill,” first released on the Snakedrill EP.

The band described it as monophonic, mono-rhythmic repetition. Then they translated it for the rest of us: “dugga dugga dugga.” Relentless single-line loops. Call and response. “Drill, drill, drill.” “Dugga, dugga, dugga.”

We’re milling through the grinder, and grinding through the mill,

If this is not an exercise, could it be a…

Could it be a…

…

Sometimes that unfinished line repeats long enough that you’re shouting “drill!”. Then it goes on so long you forget why you cared. Occasionally they finish the sentence. Sometimes they don’t. Drill. It’s an acquired taste.

Now I’ll describe this like a mechanical engineer who knows audio physics and a bit of music theory, but is resolved that he will never write engaging music critique.

Although “The Drill” sits nominally in 4/4, its rhythmic surface has virtually no accentuation of downbeat or tactus. You hear an isochronous pulse stream with no hierarchy. No dynamics. No phrasing cues. Meter becomes something you infer rather than perceive. The pulse just is.

Terse, right? Take that, Dean Suzuki. Who is, by the way, a very cool guy.

In 1990, Wire released The Drill, nearly an hour long, nine radically different versions of the same piece. Disco-adjacent versions, near-electronica, a sprawling twelve-minute live Chicago take, instrumentals like “Jumping Mint” and “Did You Dugga?” No sane producer would rush such a thing to market.

Also in 1990, I bought a 36-volt Hilti TE-10A battery-powered hammer drill. A Hilti dealer delivered it to my house in a red Hilti truck, which felt important. It was expensive and brutally heavy. Spare batteries were unthinkable, both for weight and cost. John Ganter and I used it for aid climbs underground. As far as I know, it was the first electric hammer drill used for cave exploration in West Virginia. The artifact now lives in John’s farmhouse garage, or museum.

That drill changed everything. On one battery you could place ten 3/8 x 3-inch wedge anchors. In hours you could do what had previously taken weeks with Rawl star drills or self-drives that barely engaged an inch of rock. Abuse followed, of course. Bolt farms sprouted. Some pristine pits gathered unnecessary hardware because someone thought they knew better than the last person. Alabama had already shown us the future.

Still, the potential was undeniable. When I returned to caving in 2021, Amy had a Bosch GBH18V-21. Drills were now lighter, and batteries were small and affordable. We had lists of high leads. We placed 108 bolts in a couple of months, none of them superfluous. Hunter, Casey, and Kyle, working the same cave, were bolting across ceilings, opening ridiculous routes.

Then Kyle, Max, Casey, and I started hauling drills through hours of low-airspace passages to climb beyond sumps. The drill became standard gear. You divided up the gear and double-dry-bagged it. And you brought earplugs. Ninety seconds of drilling in a confined space is wicked loud. Dugga dugga dugga.

On the drive to the cave, Max, Amy, and I traded Spotify tracks. I submitted “The Drill.” Not everyone’s taste, but it grows on you. Its flat pulse stream pairs well with the experience of standing in a swinging etrier, helmet lamp glaring, arm fully extended, ropes and gear tangling, water dripping down your back, mud in your eye. You are wearing goggles, right?

I started wondering whether actual drill audio could be mashed up with Wire’s “The Drill.” In theory, drill noise should be broadband, mostly non-harmonic. In practice, you hear pitch. A steady rotational component plus a reciprocating hammering component creates tonal structure.

I had helmet-cam footage, so I ran Fourier analysis. Once upon a time this required oscilloscopes and lab gear. Now software like Mixxx does it for free. Surprisingly, my Bosch drill consistently produces a dominant pitch around D#4, about 311 Hz. Hunter’s drilling hits the same pitch. Either we push identically, or push force doesn’t affect impact rate much. The advertised hammer rate is 5,100 BPM, or 85 Hz. The fourth harmonic lands near 340 Hz. Our load pulls it down roughly a semitone.

Our Milwaukee M12 rotary hammers center closer to C, with a hammer rate of 4,400 BPM, or 73 Hz. We push it harder than Milwaukee recommends. Otherwise it’s too slow. No motors have died yet. Its fourth harmonic is around 293 Hz. Analysis shows strong components at C3 and C4. We’re dragging it down a major second plus a bit.

DJs and the like probably do this in their sleep, or Mixxx does it for them. I made a spreadsheet. Wire’s Chicago “Drill” sits near D# minor. The A Bell Is a Cup version is in A minor. “Jumping Mint” is in C. I transposed everything to A, matched tempos, pitched the Bosch drill accordingly, then stitched audio and video together in DaVinci Resolve.

The six-minute version is reserved for future live drill events. Here’s the short cut. You might like it. Especially if you’ve ever enjoyed Pere Ubu’s singing or the sound of a machine shop.

Robert Reich, Genius

Posted by Bill Storage in Commentary on December 25, 2025

Is Robert Reich a twit, or does he just play one for money on the internet?

I never cared about Monica Lewinsky. Bill Clinton was a big-picture sort of president, like Ronald Reagan, oddly. Flawed personally, but who are we to be critical? Marriage to Hillary might test anyone’s resolve with cigars and Big Macs. Yet somehow Clinton elevated Robert Reich to Secretary of Labor. Maybe he thought Panetta and Greenspan could keep the ideologue in check.

Reich later resigned and penned Locked in the Cabinet, a “memoir” devoured by left-wing academics despite its fabricated dialogues – proven mismatches with transcripts and C-SPAN tapes. Facts are optional when the narrative sings.

Fast-forward: Reich posted this on December 23:

“Around 70% of the U.S. economy depends on consumer spending. As wealth concentrates in the richest 10%, the rest of America can’t afford to buy enough to keep the economy running.”

Classic Reich: tidy slogan, profound vibe, zero nuance, preached to the CNN faithful.

Yes, consumption is ~70% of GDP. But accounting isn’t causation. Saying the economy “runs on” consumption is like saying a car runs on exhaust because that’s what comes out the back.

Wealth concentration doesn’t vanish spending:

- High earners save more per dollar, true – but they do spend (luxury, services) and, crucially, invest.

- Investment isn’t hoarded in vaults; it funds factories, tech, startups, real estate – creating jobs and future demand. U.S. history proves inequality and growth coexist.

- The economy isn’t a closed moral ecosystem: Government spending, exports, debt expansion, asset bubbles, and credit substitution all prop things up, sometimes for a long time and sometimes disastrously. Reich’s “can’t afford” is doing heroic rhetorical labor here.

Reich smuggles in a fixed “enough” consumption – for full employment? Asset bubbles? Entitlements? That’s the debate, not premise.

His real point is political: Extreme inequality risks instability in a consumption-heavy model. Fair to argue. But he serves it as revealed truth, as if Keynes himself chiseled it.

Reich champions “labor and farmers” while blaming Trump’s tariffs for the price of beef. Thank you Robert, but, as Deming argued (unsuccessfully) to US auto makers, some people will pay more for quality. Detroit disagreed, and Toyota cleaned their clocks. Yes, I’m willing to pay more for local beef. I’m sure Bill Clinton would, had he not gone all vegan on us. Moderation, Bill, like Groucho said about his cigar.

Reich’s got bumper-sticker economics. Feels good, thinks shallow.

Bridging the Gap: Investor – Startup Psychology and What VCs Really Want to Hear

Posted by Bill Storage in Innovation management, Strategy on December 11, 2025

There’s a persistent gap between what investors want to know about startups and what founders present during their pitches. You’ll significantly improve your chance of being funded if you understand investors’ perspective and speak directly to their interests.

I speak with a bit of experience, having been on both sides of the investor conversation. Early in my career, I conducted technology due diligence for Internet Capital Group (ICG) and have since represented VC interests for $20-40M A rounds. I was also twice in the founder’s shoes, successfully raising capital for my own startups, including a $2 million round in 1998, a decent sum back then. The dynamics of pitching evolve, but the core investor psychology remains constant.

Thousands of articles list the top n things to do or not do while pitching. Here I take a more data-driven approach, grounded in investor psychology. By analyzing data on how investors consume pitch decks versus what founders emphasize in live presentations, startups can tune their pitches to align with audience interest and mental biases.

10 Essential Pitch Topics

Fifteen years ago, Sequoia Capital authored their seminal Guide to Pitching. It identified ten primary topics for a startup pitch deck, each to be covered in one or more slides:

- Purpose

- Problem

- Solution

- Why now?

- Market

- Competition

- Business model

- Team

- Financials

- Product

The Shifting Attention Span of Investors

I collected data on where founders spend their time during live pitches from the Silicon Valley Software SIG, videos of pitches found on the web, Band of Angels, and live pitch competitions in the bay area over the last ten years.

I also started tracking DocSend’s data on investors’ pitch deck interest. Their data consistently shows that the average time investors spend reviewing a pitch deck is very brief. The average time dropped from 3 minutes and 27 seconds in 2015 to just 2 minutes and 47 seconds by April 2021. The most recent data from 2024 shows an even tighter window, often averaging just 2 minutes and 35 seconds. Investors are smart, busy, and focused, so pitch decks must cover the right topics clearly and efficiently.

The Persistent Mismatch of Interests

The count of slides in a deck has averaged around 20 for years. Using that as a guide, at least one slide should cover each of the primary Sequoia topics, with some topics needing more real estate.

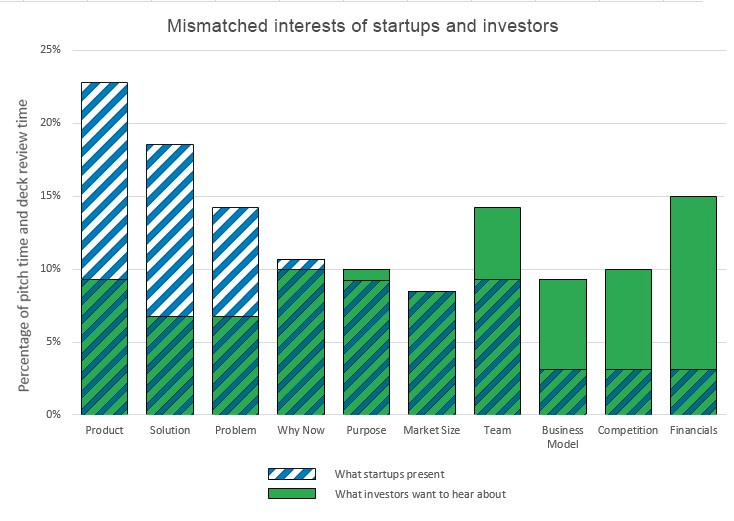

The combined data on investor viewing time versus founder presentation time reveals a clear mismatch of interest (see chart). From the investor’s perspective, founders still talk far too much about the problem, the solution, and how the product delivers the solution. Conversely, founders talk far too little about the business model, the competition, and financials.

This mismatch highlights something that may seem obvious but is too easily lost in the pursuit of developing great technology: Investors want to know how their money will translate into your growth and their eventual profitable exit. Ultimately, they want to manage their investment risk.

A Great Product Does Not Guarantee a Great Investment

Investors often need little convincing that a business problem exists and that your product is a potential solution. They trust your domain expertise on the problem. But a great product does not necessarily make a great company, and a great company is not necessarily a great investment.

To judge an investment risk as acceptable, investors need to understand your business model in detail.

- How exactly do you get paid for your product?

- What are your primary channels for customer acquisition?

- How much will it cost to acquire each new customer (CAC)?

They want to know that your sales forecasts are plausible. What size of sales force will it take if you’re projecting exponential sales increases?

Competition and Market Realities

Data presented by Ron Weissman at Band of Angels back in 2015 showed that founders gave almost no time at all to their competition. While this has improved slightly, it remains a significant weak area for most pitches.

You should be able to answer key competitive questions transparently:

- Who are your competitors now?

- Who will they be in the future?

- What is their secret sauce?

- What do you do better than all of them?

- Can you maintain that advantage in the future?

You should answer these questions without disparaging your competitors or resorting to the classic red flag that “there are no competitors” (which usually implies there is no market). Differentiation should include aspects of the business – such as distribution, partnerships, or unique data access – not just technical product features.

Focus on Scalability and Use of Funds

Investors are rarely interested in science projects. They want to see a business that can scale rapidly with an injection of capital. Your financial projections must make clear your intended use of funds.

- How much goes to hiring great talent?

- How much to marketing?

- How much to sales?

Investors understand that your projections of future revenue, market share, and customer acquisition costs are hypothetical and based on limited current information. However, they are scrutinizing your ability to think critically about scale. They want proof that it is feasible you’ll reach the key metrics required for your next round of funding before you run out of money.

This emphasis on feasibility and risk mitigation translates directly into a heightened focus on capital efficiency. In today’s market, VCs prioritize companies that can do more with less. Pitches need to clearly articulate a path to profitability or sustainable growth that minimizes cash burn. Investors want to see that founders have a credible plan to achieve significant milestones within 18-24 months without needing another immediate cash infusion. Demonstrating a capital-efficient operational plan is now as critical as projecting believable revenue growth.

I hope you find this material helpful for tuning your pitch deck to its investor audience. Please let me know if I can develop any of these points further.

Lawlessness Is a Choice, Bugliosi Style

Posted by Bill Storage in Commentary on December 8, 2025

Sloppiness is a choice. Miranda Devine’s essay, Lawlessness Is a Choice, in the October Imprimis is a furious and wordy indictment of progressive criminal-justice policies. Its central claim is valid enough: rising crime in Democratic cities is a deliberate ideological choice. Her piece has two fatal defects, at least from the perspective of a class I’m taking on on persuasive writing. Her piece is argued badly, written worse. Vincent Bugliosi, who prosecuted Charles Manson, comes to mind – specifically, the point made in Outrage, his book about the OJ Simpson trial. Throwing 100 points at the wall dares your opponent to knock down the three weakest, handing them an apparent victory over the entire case.

Devine repeats “lawlessness is a choice” until it sounds like a car alarm. She careens from New York bail reform to Venezuelan gangs to Antifa assassination. Anecdotes are piled on statistics piled on sarcasm until you’re buried under heap of steaming right-wing indignation.

Opponents are “nutty,” “deranged,” “unhinged,” or “turkeys who voted for Thanksgiving.” 20 to 25 million “imported criminals.” Marijuana is the harbinger of civilizational collapse. Blue-city prosecutors personally orchestrate subway assaults. Devine violates Bugliosi’s dictum throughout.

Easily shredded claims:

- Unsourced assertions of “20-25 million imported criminals.”

- Blanket opposition to marijuana decriminalization, conflating licensed dispensaries with open-air drug markets and public defecation as equally obvious “broken windows” offenses, even though two-thirds of Americans now support legal pot and several red states have thriving regulated markets.

- Stating that Antifa was plotting to assassinate Trump with no citation.

- Ignoring red-state violent-crime rates that sometimes exceed those of the blue cities she condemns.

A competent MSNBC segment producer – there may be one for all I know – could demolish the above in five minutes and then declare Devine’s whole law-and-order critique “conspiracy theory.” The stronger arguments – recidivism under New York’s bail reform, collapse of subway policing after 2020, the chilling effect of the Daniel Penny prosecution, the measurable crime drop after Trump’s 2025 D.C. National Guard deployment – are drowned in the noise.

The tragedy is that Devine is mostly right. Progressive reforms since 2020 (no-cash bail with no risk assessment, de facto decriminalization of shoplifting under $950, deliberate non-enforcement of quality-of-life offenses) have produced predictable disorder. The refusal of elite progressive voices to acknowledge personal agency is corrosive.

Bugliosi would choose his ground and his numbers carefully, conceding obvious points (red states have violent crime too), He wouldn’t be temped to merge every culture-war grievance. Devine chose poorly, and will persuade no one who matters. Now if Bugliosi had written it…

Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, the defense will tell you that crime spikes in American cities are complicated – poverty, guns, COVID, racism, underfunding. I lay out five undisputed facts, that in the years 2020–2024 major Democratic cities deliberately chose policies that produced disorder. They were warned. When the predicted outcome happened, they denied responsibility. That is not complexity but choice.

Count 1 – New York’s bail reform (2019–2020): The law eliminated cash bail for most misdemeanors and non-violent felonies, and required judges to release defendants with the “least restrictive” conditions. Funding was unchanged. Result: 2020-2023 saw over 10,000 rearrests of people released under the new law for new felonies while awaiting. In 2022 alone, at least 107 people released under bail reform were rearrested for murder or attempted murder. The legislature was warned. They passed it anyway. Choice.

Count 2 – Subway policing collapse: In January 2020 the NYPD had 2,500 uniformed officers assigned to the subway system. By late 2022 it was under 1,000. Felony assaults in the subway system rose 53 % from 2019 to 2023. This was deliberate de-policing ordered by City Hall and the Manhattan DA. Choice.

Count 3 – San Francisco’s Prop 47 and the $950 rule: California reclassified theft under $950 as a misdemeanor. Shoplifting reports in San Francisco rose 300%. Chain pharmacies closed 20 stores, citing unsustainable theft. The legislature refused every attempt to raise the threshold or mandate prosecution. Choice.

Count 4 – The Daniel Penny prosecution: Marine veteran Daniel Penny restrains a man who was screaming threats on a subway car. The man dies. Manhattan DA Alvin Bragg charges Penny with manslaughter. After two years of trial and massive expense, a jury acquits on the top count and deadlocks on the lesser; Bragg drops the case. Message sent: if you intervene to protect others, you roll the dice on court and possible prison. That chilling effect was the entire point of the prosecution. Choice.

Count 5 – The 2025 Washington, D.C. experiment: President Trump federalizes the D.C. National Guard and surges 3,000 troops plus federal agents into high-crime areas. Result in first 100 days: carjackings down 82%, homicides down 41%, robberies down 31% No gun buybacks – just enforcement. When the policy is reversed by court order, the numbers rose again within weeks. Enforcement works; the absence of enforcement is a choice.

Five exhibits, all public record. No unsourced 25-million-migrant claims, no Antifa conspiracy theories, nothing about Colorado potheads. Five policy decisions, five warnings ignored, five measurable explosions in disorder, and one rapid reversal when enforcement returned.

The defense will now tell you all about root causes. But I remind you that no city was forced to remove all consequences for criminal behavior. They were warned. They chose. They own the results. Lawlessness is a choice.

Fattening Frogs For Snakes

Posted by Bill Storage in Fiction on December 2, 2025

(Sonny Boy Williamson’s blues classics reinterpreted)

1.

Three a.m. and the coffee skin was thick enough to skate across. I listened for heels on the stairs, the click of the screen door, but heard only the refrigerator humming a tune it couldn’t possibly know.

Took me a long time, long time to find out my mistake

You can bet your bottom dollar, ain’t fattening no more frogs for snakes

I had told her the frog-and-snake thing over venison and morels I picked myself above the ruined mill on Deep Creek. She’d worn a blue-green dress that looked like pond water reflecting setting sun. I remember thinking: that’s the color a man drowns in. She smiled at the frog and snake story. I tried to catalog the smile. Amusement? Patience? Or the kindness of someone who knows you’re performing before you know it yourself.

Now, she dreamed that I was a kissin’ her

On down by the mill

She’d dream that she’d taken me from

That girl up on the hill

Beneath the front window leaned her unicorn clock (acrylic on wood, fine art kissing kitsch), its hands frozen for years. She loved the useless thing. I measured the dead mechanism, then lost an hour on Amazon picking the exact shaft diameter, thread length, hand style. Details matter.

But first, could we find out what went wrong? I disconnected, tested continuity, checked for a bind, and listened again. The hum – or its absence – could tell me nothing. Still, I traced the edge of the case, felt for the tiniest resistance, imagined the coil shifting beneath my touch.

She asked if frogs really tasted like knowledge. I said only if you cooked them slow, with doubt and regret. She laughed so hard the candle guttered. But I’d just put more snake on the table than I’d meant to. She caught the mote of a pause when I stopped myself from straightening the candle.

She was the dreamest girl

The dreamest girl I most ever seen

The new movement arrived with six pairs of hands. I laid them out like tarot cards, wondering if anyone would notice an hour hand married to the wrong minute. I’d measured the inset twice and chosen the three-eighths movement, though I had doubts about the depth. Just in case, I’d already walked to Ace for a single Everbilt fender washer, bright enough to show every fingerprint of doubt.

Installation took thirty seconds. The old mechanism went into a drawer with all the other pieces that once belonged somewhere. The clock looked identical, but felt somehow different, like it had learned a secret.

That was the night I felt the first cold coil around my ankle.

Later, when the affair was coughing blood, I blamed more worldly men. I can’t dance – it doesn’t load right. I pictured them in Teslas, playing jazz, their beards shaped like the decisions they agonize over.

Oh been so long, been a mighty long time.

Yes a mighty long time since I seen that girl of mine

Sometimes, driving the back roads at dusk, I’d pass a slough and see her reflection in black water. Sometimes the reflection had my face. Sometimes it smiled like it knew the joke. Frog? Or snake?

2.

He was gone and the kissing dreams had faded. Who won the breakup?

I keep taking the same left past a collapsed barn with the Sinclair sign still bleeding green, and somehow I’m always coming up on it again. You saw it on Twilight Zone. The odometer isn’t moving. That’s how I know I’m still inside the dream he left me.

My mind was a room he enjoyed furnishing. I’d sit on the counter while he cooked – I couldn’t boil water when we met. I’ll grant him that. And he’d feed me concepts the way other men feed you strawberries. I grew up with X-Files and Nine Inch Nails. He gave me real art, history, literature. Not pretentious crap but the kind you hoard. I grew fat on it. Addicted.

Like I need an addiction. My thought turned sleek and cold-blooded.

My dreams inverted. I’d be sitting alone, and liking it, then there he’d be, fixing things I never used, and things that were broken but worked well enough. He seemed to audition for intimacy.

Now an’ I’m goin’ away, baby

Just to worry you off my mind

Tonight, I cook. I’m craving chicken. I’m not seeking fame here, just something with enough moving parts to keep me honest. The ingredients line up like suspects. Shallots, white wine, a sprig of thyme that’s tired but still willing. The thighs wait off to the side, trimmed and patted dry. Salt and pepper both sides. I want crisp skin.

Skin down in the pan, they hissed at me, and the smell shifted from raw to something that makes the neighbors reconsider their life choices. I did. Don’t fuss with the thighs. If you poke too early, the skin will tear.

I mince my shallots microscopic. Knife work is the closest thing I have to meditation. There’s no arguing with a blade that demands truth. From an onion or otherwise.

I remove the chicken once it loosens from the pan. In go the shallots, and the wine lifts the browned bits. The sauce pulls itself together and thickens like a story with unneeded characters. Heat on low.

I’d be walking the ridge and the ground would soften, turn to loam, then to water. I’d sink to the ankles, then the knees, and something muscular would brush my calf. No bite, just tasting the temperature. I looked down and saw his face under the surface, mouth open in a silent croak. Then it was my own face, older, eyes already filmed with the green of deep water.

I add stock, thyme, a whisper of cream. Soften it. Chicken back in the pan and then simmer. I load the D-minor Partita on Spotify and headphones.

The sauce coats the back of a spoon. I taste it, and it tastes back, which is how you know you’ve gotten somewhere. I plate the chicken with potatoes. Nothing theatrical. Just a little structure.

Snakes? Now the Bible prefers linear time, a story with a big bang and an end. Not loops, endless returns, and recurrence. The ouroboros, the snake that eats its tail, showed up in Greece and Mesopotamia. Put a cyclic symbol creature inside a linear story and you got tension.

Behind a clock face is a nest of gears that no one sees. Most folk just look at the hands. I tried replacements. They spoke depth in the voice of a dryer sheet with a taste for Wikipedia. None leave tracks when they walk across a lit room. None make the air go thick and listenable.

I wake up pounding my fist on the bed. I’m quoting dead Germans and want to bite my own tongue off. One says clocks murder everything alive about time, turn it into a corpse on a conveyor belt. I know their names. I can quote them. But why? Knowledge I wish I didn’t have, I tell myself, humming the partita.

Don’t start me to talkin’. I’ll tell everything I know.

Last week I found a morel growing through the floorboard of my car. Passenger side. I think I might be dreaming someone who’s trying to wake up from me. The Sinclair sign’s still bleeding green and the odometer hasn’t budged.

Oh been so long, been a mighty long time.

3.

The woman came at the blue hour when the bats stitch the sky together. She stood on the plank that used to be a dance floor before the flood of ’63 carried the jukebox down Deep Creek still playing Sonny Boy. She touched the face in the reflection.

She looked thinner. Hunger can do that, even if it’s the mind that’s starving.

She asked the water the questions people always ask when the music stops:

“Did he love me the way a man loves a woman, or the way a man loves a mirror?”

“Did I love him, or did I love being transformed into someone worth ruining?”

It was like she had read the script. I pressed a smile back down and let one eye break the surface.

“You loved me,” I told her.

She stood on the bank. A turtle hauled itself onto a sun-warmed log. Something regal in its refusal to hurry. The turtle blinked slowly, a gesture suggesting amusement. I nodded, thin as a drawn line – acknowledging the age, the armor, the calm.

The water held the crooked reflections of bottlebrush sedge. A few loose seeds clung to the stems. When a dragonfly landed, the stem leaned, and the whole cluster tilted just a hair.

She stepped in. The water took her weight without sound. Her hand found mine. Cold met cold. The scales remembered every classic she’d devoured whole.

I tasted the new skin budding under the old one – thin, translucent, the color of creek ice at breakup.

Above us, the mill wheel groaned. The years ran backward: the flood returned the jukebox, the mill stood up straight. The venison walked back into deer. Somewhere a screen door clicked shut.

I live it through my diary

And I read all my problems now are free

“Grow a new skin,” I told her. “You’ve earned it.”

And in that hush, I slipped beneath the water, silent on the downbeat.

Don’t start me to talkin’. I’ll tell everything I know.

___

.

Carving the Eagle

Posted by Bill Storage in Commentary on November 27, 2025

If Ben Franklin had gotten his way, we’d have an edible national bird. Or no one would eat turkey on Thanksgiving. That might be ok by me.

Franklin was obsessed with it. He pushed for the wild turkey as our national bird. “Bird of courage” he said, roasting the bald eagle as having “bad moral character” for stealing fish from hard-working hawks. Imagine Franklin’s Thanksgiving. Either we’d be carving an eagle, or we’d eat ham, and nobody would miss two weeks of dry breast meat.

America, commerce always first, probably opted for turkey because it’s big and easy to farm, once tamed by government subsidy. Franklin lost that round, but he did get his face on the hundred-dollar bill.

“Turkey!” as an insult peaked in the US in the 1980s, due to National Lampoon’s 1975 Gold Turkey, and then Christmas Vacation (1989). It originated in theater. A “turkey” was a flop show that opened on Thanksgiving, anticipating a run til New Year, and closed fast. By the 50s it was niche. Belushi brought it back. Kids still use it.

Despite Franklin, Congress went with the eagle as the official bird, and 250 years later the turkey’s ultimate revenge was becoming the official insult. Turkey was relegated to grocery store and playground.

That’s a truly American outcome. We didn’t crown the turkey, we commodified it, mocked it, and ate it out of habit. Poor Ben. We turned his bird of courage into a riff for failure. For a man who valued thrift, civic virtue, and self-improvement, that must be the final insult.

If Franklin could see us now, he’d shake his head, pocket his hundred, and call us what we’ve become. Turkeys.

It’s the Losers Who Write History

Posted by Bill Storage in Commentary on November 24, 2025

The victors write first drafts. They get to seize archives, commission official chronicles, destroy inconvenient records, and shape the immediate public memory. Take Roman accounts of Carthage and Spanish on the Aztecs. What happens afterward and indefinitely is where Humanities departments play an outsized role in canonization.

Such academics are the relativist high priests of the safe-space seminary – tenured custodians of western-cultural suicide. Their scripture is the ever-shifting DEI bulletin. Credentialed barbarians stand behind at the gates they themselves dismantled. They are moral vacationers who turned the university into a daycare for perpetual adolescents. The new scholastic is the aristocracy of mediocrity. Historicist gravediggers have pronouncing the West dead so they can inherit its estate.

Several mechanisms make this possible. Academic historians, not primary sources – whether Cicero or Churchill – decide which questions are worth asking. Since the 1970s especially, new methodologies like social history, postcolonial studies, gender studies, and critical race theory have systematically shifted focus away from political, military, and diplomatic chronicling toward power structures, marginalized voices, and systemic oppression. These are not neutral shifts. They reflect the political priorities of the post-Nixon academic left, which has dominated western humanities departments since.

Peer-reviewed journals, university presses, hiring committees, and tenure standards are overwhelmingly controlled by scholars who share an ideological range scarcely wider than a breath. Studies of political self-identification among historians routinely show ratios of 20:1 or higher in favor of the left – often contented Marxists. Dissenting or traditional interpretations that challenge revisionist views on colonialism, the Soviet Union, or America’s founding are marginalized, denied publication, and labeled “problematic.” A career is erased overnight.

K-12 and undergraduate curricula worship academic consensus. Here, again, is a coherence theory of truth subjugating the correspondence model. When the consensus changes – when a critical mass of scholars finds an even more apologetic lens – textbooks follow, almost instantly. The portrayal of the European Age of Exploration, for example, went overnight from celebration of discovery to exclusive emphasis on conquest and genocide. American Founding Fathers went from flawed but visionary innovators of a unique government to rich slave-owning hypocrites, especially after the 1619 Project gained academic traction. A generation or two of Humanities college grads have no clue that “rich white man” Alexander Hamilton was born illegitimate in the Caribbean, was a lifelong unambiguous abolitionist, despised the slave-based Southern economic model, and died broke. They don’t know that the atheist Gouverneur Morris at the Constitutional Convention called slavery “a nefarious institution … the curse of heaven on the states where it prevailed.” They don’t know this because they’ve never heard of Gouverneur Morris, the author of the final draft of the Constitution. That’s because Ken Burns never mentions Morris in his histories. It doesn’t fit his caricature. Ken Burns is where intellectuals learn history. His The Vietnam War is assigned in thousands of high-school and college courses as authoritative history.

Modern historians openly admit that they mean their work to serve social justice goals. The past is mined for precedents, cautionary tales, or moral leverage rather than reconstructed for its own sake. The American Historical Association’s own statements have emphasized “reckoning with the past” in explicitly activist language. Howard Zinn (A People’s History of the United States) boasted, “I don’t pretend to be neutral.”

The academic elite – professional mourners at the funeral of the mind they themselves poisoned – have graduated an entire generation who believe Nixon escalated (if not started) the Vietnam War. This is a textbook (literally) case of the academic apparatus quietly rewriting the emphasis of history. Safe-space sommeliers surely have access to original historical data, but their sheep are too docile to demand primary sources. Instead, border patrollers of the settler-colonial imagination serve up moral panic by the pronoun to their trauma-informed flock.

The numbers. Troop levels went from 1000 when Kennedy took office to 184,000 in 1965 under Johnson. A year later they hit 385,000, and peaked at 543,000 when Nixon took office in 1969. Nixon’s actual policy was systematic de-escalation; he reduced US troops to 24,000 by early 1973, then withdrew the U.S. from ground combat in March. But widely used texts like The American Pageant, Nation of Nations, and Visions of America ignore Kennedy’s and Johnson’s role while framing Nixon as the primary villain of the war. And a large fraction of the therapeutic sheep with Che Guevara posters in their dorms graze contentedly inside an electric fence of approved opinions. They genuinely believe Nixon started Vietnam, and they’re happy with that belief.

If Allan Bloom – the liberal Democrat author of The Closing of the American Mind (1987) – were somehow resurrected in 2025 and lived through the Great Awokening, I suspect he’d swing pretty far into the counter-revolutionary space of Victor Davis Hanson. He’d scorch the vanguardist curators of the neopuritan archival gaze and their pronoun-pious lambs who bleat “decolonize” while paying $100K a year to be colonized by the university’s endowment.

Ken Burns said he sees cuts to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting as a serious existential threat. He did. The republic – which he calls a democracy – is oh so fragile. He speaks as though he alone has been appointed to heal America’s soul. It’s the same sacerdotal NPR manner that Bloom skewered in the humanities professoriate: the priestly conviction that one is engaged in something higher than mere scholarship, something redemptive. And the nation keeps paying Burns for it, because it’s so much more comfortable to cry over a Burns film than to wrestle with the actual complexity Burns quietly edits out. He’s not a historian. He’s the high priest of the officially sanctioned memory palace. It’s losers like Burns who write history.

Anger As Argument – the Facebook Dividend

Posted by Bill Storage in Commentary, Ethics on January 16, 2026

1. Your partner has ordered the trolley conductor to drive away. If you order her to step out of the vehicle, and you briefly set foot on the track, you can repeatedly shoot her in the head and send the trolley careening out of control, possibly taking out another commie liberal, and the president will hail you as a hero. What do you do?

2. You’re at a crossroads and the only way to save your governor’s career and reputation is to take one for the team. Out of nowhere the frazzled ICE agent you’ve been threatening for days steps onto the trolley track. You can choose to sacrifice yourself in a final heroic act, slamming into that threat, keeping the governor safe and leaving your child an orphan. Do it now, or let Trump’s chaos reign. What’s your move?

The original trolley problems aimed at making you think. It was a philosophical puzzle used to explore moral reasoning, utilitarianism and deontology. Both versions above turn the trolley problem into a caricature. One paints federal force as the unstoppable threat that must be violently halted, the other paints civil disobedience as the lethal danger that must be neutralized. Each is designed to elicit tribal fervor.

These caricatures work on Facebook not because they clarify moral structure but because they flatter the reader and stage moral theater. The audiences already know who the villain is and get to enjoy the feeling of having seen through it all. Smug sarcasm supplies the laugh track.

What’s most depressing is the way such “humor” gets conscripted. Old fashioned wit punctured pretension and left everyone a bit exposed. This humor is ritualized sneer, a war cry that signals membership. Moral superiority and righteous indignation arrive prepackaged.

Whichever side you pick, your rage is justified. Anger becomes proof of righteousness. If I can mock you, I don’t need to understand you. If I can make others laugh at you, I don’t need to persuade them. Emotional reward comes first, the argument is decorative trim. I am furious. Therefore the offense must be enormous. My fury is not only justified but morally required. Anger stops being a response and becomes evidence. The hotter it burns, the stronger the proof. On Facebook this logic is amplified.

Philosophy, ethics, and moral reasoning slow things down. Facebook collapses time, context, and agency into a single cinematic moment. Pull the lever and cue the likes. Facebook rewards train people out of moral curiosity. Once sarcasm becomes the marker of insight, asking a genuine question is read as weakness. The platform punishes those who don’t escalate.

If something is free, the product is you. Facebook loves your self-justifying rage because rage compresses so well. A qualified objection is no match for indignation. Agreement becomes a reflex response. Once anger functions as proof, escalation is inevitable. Disagreement cannot be good faith. Arguments cease to be about the original claim and switch to the legitimacy of self-authenticating anger itself.

Facebook provides the perfect stage because it removes the costs that normally discipline rage. There’s no awkward pause, just instant feedback and dopamine.

To be taken seriously, you have to be outraged. You have to perform belief that the stakes are absolute. If your performance is good, you convince yourself. Likes makes right. Everything is existential. Restraint is complicity. The cycle continues. Facebook counts the clicks and sells them to Progressive Insurance, Apple, and Amazon.

___

Via Randall Munroe, xkcd

anger, history, politics, writing

4 Comments