Posts Tagged history

Popular Miscarriages of Science, part 3 – The Great Lobotomy Rush

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science on January 25, 2024

On Dec. 16, 1960, Dr. Walter Freeman told his 12-year-old patient Howard Dully that he was going to run some tests. Freeman then delivered four electric shocks to Dully to put him out, writing in his surgery notes that three would have been sufficient. Then Freeman inserted a tool resembling an ice pick above Dully’s eye socket and drove it several inches into his brain. Dully’s mother had died five years earlier. His stepmother told Freeman, a psychiatrist, that Dully had attacked his brother, something the rest of Dully’s family later said never happened. It was enough for Freeman to diagnose Dully as schizophrenic and perform another of the thousands of lobotomies he did between 1936 and 1967.

“By some miracle it didn’t turn me into a zombie,” said Dully in 2005, after a two-year quest for the historical details of his lobotomy. His story got wide media coverage, including an NPR story called My Lobotomy’: Howard Dully’s Journey. Much of the media coverage of Dully and lobotomies focused on Walter Freeman, painting Freeman as a reckless and egotistical monster.

Weston State Hospital (Trans-Allegheny Lunatic Asylum), photo courtesy of Tim Kiser

In The Lobotomy Letters: The Making of American Psychosurgery, (2015) Mical Raz asks, “Why, during its heyday was there nearly no objection to lobotomy in the American medical community?” Raz doesn’t seem to have found a satisfactory answer.

(I’m including a lot of in-line references here, not to be academic, but because modern media coverage often disagrees with primary sources and scholarly papers on the dates, facts, and numbers of lobotomy. It appears that most popular media coverage seemed to use other current articles as their sources, rather than going to primary sources. As a trivial example, Freeman’s notes report that in Weston, WV, he did 225 lobotomies in 12 days. The number 228 is repeated in all the press on Howard Dully. This post is on the longer side, because the deeper I dug, the less satisfied I became that we have learned the right lesson from lobotomies.)

A gripping account of lobotomies appeared in Dr. Paul Offit’s (developer of the rotavirus vaccine) 2017 Pandora’s Lab. It tells of a reckless Freeman buoyed by unbridled media praise. Offit’s piece concludes with a warning about wanting quick fixes. If it seems too good to be true, it probably is.

In the 2005 book, The Lobotomist: A Maverick Medical Genius and his Tragic Quest to Rid the World of Mental Illness, Jack El-Hai gave a much more nuanced account, detailing many patients who thought their lobotomies hade greatly improved their lives. El-Hai’s Walter Freeman was on a compassionate crusade to help millions of asylum patients escape permanent incarceration in gloomy state mental institutions. El-Hai documents Freeman’s life-long postoperative commitment to his patients, crisscrossing America to visit the patients that he had crisscrossed America to operate on. Despite performing most of his surgery in state mental hospitals, Freeman always refused to operate on people in prison, against pressure from defense attorneys’ pleas to render convicts safe for release.

Contrasting El-Hai’s relatively kind assessment, the media coverage of Dully aligns well with Offit’s account in Pandora’s Lab. On researching lobotomies, opinions of the medical community, and media coverage, I found I disagreed with Offit’s characterization of the media coverage, more about which below. In all these books I saw signs that lobotomies are a perfect instance of bad science in the sense of what Thomas Kuhn and related thinkers would call bad science, so I want to dig into that here. I first need to expand on Kuhn, his predecessors, and his followers a bit.

Kuhn’s Precursors and the Kuhnian Groupies

Kuhn’s writing, particularly Structure of Scientific Revolutions, was unfortunately ambiguous. His friends, several of whom I was lucky enough to meet, and his responses to his critics tell us that he was no enemy of science. He thought science was epistemically special. But he thought science’s claims to objectivity couldn’t be justified. Science, in Kuhn’s view, was not simply logic applied to facts. In Structure, Kuhn wrote many things that had been said before, though by sources Kuhn wasn’t aware of.

Karl Marx believed that consciousness was determined by social factors and that thinking will always be ideological. Marx denied that what Francis Bacon (1561-1626) had advocated was possible. I.e., we can never intentionally free our minds of the idols of the mind, the prejudices resulting from social interactions and from our tribe. Kuhn partly agreed but thought that communities of scientists engaged in competitive peer review could still do good science.

Ludwik Fleck’s 1935 Genesis and Development of a Scientific Fact argued that science was a thought collective of a community whose members share values. In 1958, Norwood Hanson, in Patterns of Discovery, wrote that all observation is theory-laden. Hanson agreed with Marx that neutral observation cannot exist, so neither can objective knowledge. “Seeing is an experience. People see, not their eyes,” said Hanson.

Most like Kuhn was Michael Polanyi, a brilliant Polish polymath (chemist, historian, economist). In his 1946 Science, Faith and Society, Polanyi wrote that scientific knowledge was produced by individuals under the influence of the scientific collectives in which they operated. Polanyi long preceded Kuhn, who was unaware of Polanyi’s work, in most of Kuhn’s key concepts. Unfortunately, Polanyi’s work didn’t appear in English until after Kuhn was famous. An aspect of Polanyi’s program important to this look at lobotomies is his idea that competition in science works like competition in business. The “market” determines winners of competing theories based on the judgments of its informed participants. Something like a market process exists within the institutional structure of scientific research.

Kuhn’s Structure was perfectly timed to correspond to the hippie/protest era, which distrusted big pharma and the rest of science, and especially the cozy relationships between academia, government, and corporations – institutions of social and political power. Kuhn had no idea that he was writing what would become one of the most influential books of the century, and one that became the basis for radical anti-science perspectives. Some communities outright declared war on objectivity and rationality. Science was socially constructed, said these “Kuhnians.” Kuhn was appalled.

A Kuhnian Take on Lobotomies

Folk with STEM backgrounds might agree that politics and influence can affect which scientific studies get funded but would probably disagree with Marx, Fleck, and Hanson that interest, influence, and values permeate scientific observations (what evidence gets seen and how it is assimilated), the interpretation of measurements and data, what data gets dismissed as erroneous or suppressed, and finally the conclusions drawn from observations and data.

The concept of social construction is in my view mostly garbage. If everything is socially constructed, then it isn’t useful to say of any particular thing that it is socially constructed. But the Kuhnians, who, oddly, have now come to trust institutions like big pharma, government science, and Wikipedia, were right in principle that science is in some legitimate sense socially constructed, though they were perhaps wrong about the most egregious cases, then and now. The lobotomy boom seems a good fit for what the Kuhnians worried about.

If there is going to be a public and democratic body of scientific knowledge (science definition 2 above) based on scientific methods and testability (definition 1 above), some community of scientists has to agree on what has been tested and falsified for the body of knowledge to get codified and publicized. Fleck and Hanson’s positions apply here. To some degree, that forces definition 3 onto definitions 1 and 2. For science to advance mankind, the institution must be cognitively diverse, it must welcome debate and court refutation, and it must be transparent. The institutions surrounding lobotomies did none of these. Monstrous as Freeman may have been, he was not the main problem – at least not the main scientific problem – with lobotomies. This was bad institutional science, and to the extent that we have missed what was bad about it, it is ongoing bad science. There is much here to make your skin crawl that was missed by NPR, Offit’s Pandora’s Lab, and El-Hai’s The Lobotomist.

Background on Lobotomy

In 1935 António Egas Moniz (1874–1955) first used absolute alcohol to destroy the frontal lobes of a patient. The Nobel Committee called it one of the most important discoveries ever made in psychiatric medicine, and Moniz became a Nobel laureate in 1949. In two years Moniz oversaw about 40 lobotomies. He failed to report cases of vomiting, diarrhea, incontinence, hunger, kleptomania, disorientation, and confusion about time in postoperative patients who lacked these conditions before surgery. When the surgery didn’t help the schizophrenia or whatever condition it was done to cure, Moniz said the patients’ conditions had been too advanced before the surgery.

In 1936 neurologist Walter Freeman, having seen Moniz’s work, ordered the first American lobotomy. James Watts of George Washington University Hospital performed the surgery by drilling holes in the side of the skull and removing a bit of brain. Before surgery, Freeman lied to the patient, who was concerned that her head would be shaved, about the procedure. She didn’t consent, but her husband did. The operation was done anyway, and Freeman declared success. He was on the path to stardom.

The patient, Alice Hammatt, reported being happy as she recovered. A week after the operation, she developed trouble communicating, was disoriented, and experienced anxiety, the condition the lobotomy was intended to cure. Freeman presented the case at a medical association meeting, calling the patient cured. In that meeting, Freeman was surprised to find that he faced criticism. He contacted the local press and offered an exclusive interview. He believed that the press coverage would give him a better reception at his next professional lobotomy presentation.

By 1952, 18,000 lobotomies had been performed in the US, 3000 of which Freeman claimed to have done. He began doing them himself, despite having no training in surgery, after Watts cut ties because of Freeman’s lack of professionalism and sterilization. Technically, Freeman was allowed to perform the kind of lobotomies he had switched to, because it didn’t involve cutting. Freeman’s new technique involved using a tool resembling an ice pick. Most reports say it was a surgical orbitoclast, though Freeman’s son Frank reported in 2005 that his father’s tool came right out their kitchen cabinet. Freeman punched a hole through the eye sockets into the patient’s frontal lobes. He didn’t wear gloves or a mask. West Virginians received a disproportionate share of lobotomies. At the state hospital in Weston, Freeman reports 225 lobotomies in twelve days, averaging six minutes per procedure. In The Last Resort: Psychosurgery and the Limits of Medicine (1999), JD Pressman reports a 14% mortality rate in Freeman’s operations.

The Press at Fault?

The press is at the center of most modern coverage of lobotomies. In Pandora’s Lab, Offit, as in other recent coverage, implies that the press overwhelmingly praised the procedure from day one. Offit reports that a front page article in the June 7, 1937 New York Times “declared – ‘in what read like a patent medicine advertisement – that lobotomies could relieve ‘tension apprehension, anxiety, depression, insomnia, suicidal ideas, …’ and that the operation ‘transforms wild animals into gentle creatures in the course of a few hours.’”

I read the 1937 Times piece as far less supportive. In the above nested quote, The Times was really just reporting the claims of the lobotomists. The headline of the piece shows no such blind faith: “Surgery Used on the Soul-Sick; Relief of Obsessions Is Reported.” The article’s subhead reveals significant clinical criticism: “Surgery Used on the Soul-Sick Relief of Obsessions Is Reported; New Brain Technique Is Said to Have Aided 65% of the Mentally Ill Persons on Whom It Was Tried as Last Resort, but Some Leading Neurologists Are Highly Skeptical of It.”

The opening paragraph is equally restrained: “A new surgical technique, known as “psycho-surgery,” which, it is claimed, cuts away sick parts of the human personality, and transforms wild animals into gentle creatures in the course of a few hours, will be demonstrated here tomorrow at the Comprehensive Scientific Exhibit of the American Medical Association…“

Offit characterizes medical professionals as being generally against the practice and the press as being overwhelmingly in support, a portrayal echoed in NPR’s 2005 coverage. I don’t find this to be the case. By Freeman’s records, most of his lobotomies were performed in hospitals. Surely the administrators and staff of those hospitals were medical professionals, so they couldn’t all be against the procedure. In many cases, parents, husbands, and doctors ordered lobotomies without consent of the patient, in the case of institutionalized minors, sometimes without consent of the parents. The New England Journal of Medicine approved of lobotomy, but an editorial in the 1941 Journal of American Medical Association listed the concerns of five distinguished critics. As discussed below, two sub-communities of clinicians may have held opposing views, and the enthusiasm of the press has been overstated.

In a 2022 paper, Lessons to be learnt from the history of lobotomy, Oivind Torkildsen of the Department of Clinical Medicine at University of Bergen wrote that “the proliferation of the treatment largely appears to have been based on Freeman’s charisma and his ability to enthuse the public and the news media.” Given that lobotomies were mostly done in hospitals staffed by professionals ostensibly schooled in and practicing the methods of science, this seems a preposterous claim. Clinicians would not be swayed by tabloids.

A 1999 article by GJ Diefenbach in the Journal of the History of the Neurosciences, Portrayal of Lobotomy in the Popular Press: 1935-1960, found that the press initially used uncritical, sensational reporting styles, but became increasingly negative in later years. The article also notes that lobotomies faced considerable opposition in the medical community. It concluded that popular press may have been a factor influencing the quick and widespread adoption of lobotomy.

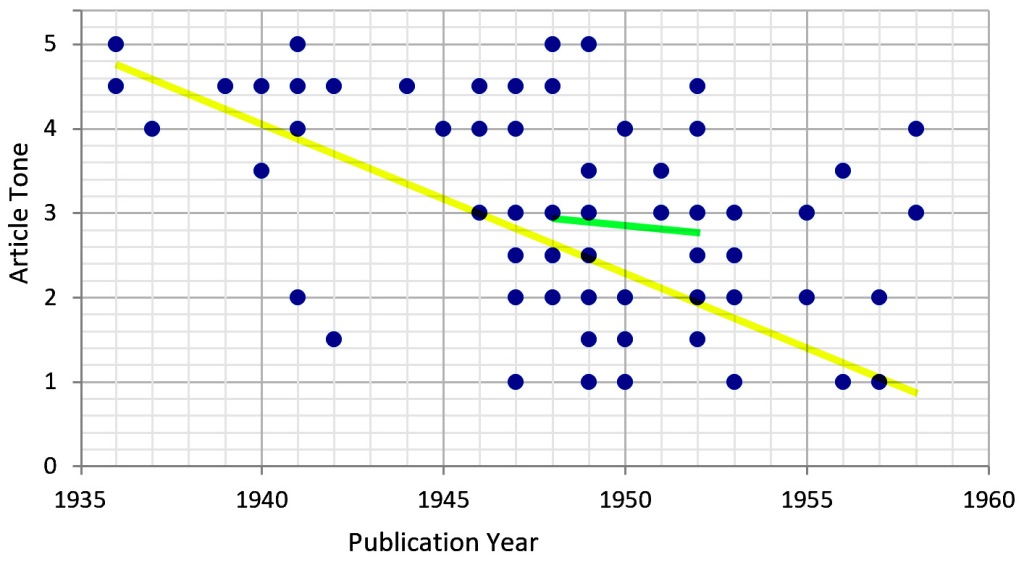

The article’s approach was to randomly distribute articles to two evaluators for quantitative review. The reviewers then rated the tone of the article on a five-point scale. I plotted its data, and a linear regression (yellow line below) indeed shows that the non-clinical press cooled on lobotomies from 1936 to 1958 (though, as is apparent from the broad data scatter, linear regression doesn’t tell the whole story). But the records, spotty as they are, of when the bulk of lobotomies were performed should also be considered. Of the 20,000 US lobotomies, 18,000 of them were done in the 5-year period from 1948 to 1952, the year that phenothiazines entered psychiatric clinical trials. A linear regression of the reviewers’ judgements over that period (green line) shows little change.

Applying the Methods of History and Philosophy of Science

One possibility for making sense of media coverage in the time, the occurrence of lobotomies, and the current perception of why lobotomies persisted despite opposition in the medical community is to distinguish between lobotomies done in state hospitals from those done in private hospitals or psychiatrists’ offices. The latter category dominated the press in the 1940s and modern media coverage. The tragic case of Rosemary Kennedy, whose lobotomy left her institutionalized and abandoned by her family and that of Howard Dully are far better known that the 18,000 lobotomies done in American asylums. Americans were not as in love with lobotomies as modern press reports. The latter category, private hospital lobotomies, while including some high-profile cases, was small compared to the former.

Between 1936 and 1947, only about 1000 lobotomies had been performed in the US, despite Howard Freeman’s charisma and self-promotion. We, along with Offit and NPR, are far too eager to assign blame to Howard Freeman the monster than to consider that the relevant medical communities and institutions may have been monstrous by failing to critically review their results during the lobotomy boom years.

This argument requires me to reconcile the opposition to lobotomies appearing in medical journals from 1936 on with the blame I’m assigning to that medical community. I’ll start by noting that while clinical papers on lobotomy were plentiful (about 2000 between 1936 and 1952), the number of such papers that addressed professional ethics or moral principles was shockingly small. Jan Frank, in Some Aspects of Lobotomy (Prefrontal Leucotomy) under Psychoanalytic Scrutiny (Psychiatry 13:1, 1950) reports a “conspicuous dearth of contributions to the theme.” Constance Holden, in Psychosurgery: Legitimate Therapy or Laundered Lobotomy? (Science, Mar. 16, 1973), concluded that by 1943, medical consensus was against lobotomy, and that is consistent with my reading of the evidence.

Enter Polanyi and the Kuhnians

In 2005, Dr. Elliot Valenstein (1923-2023), 1976 author of Great and Desperate Cures: The Rise and Decline of Psychosurgery, in commenting on the Dully story, stated flatly that “people didn’t write critical articles.” Referring back to Michael Polanyi’s thesis, the medical community failed itself and the world by doing bad science – in the sense that suppression of opposing voices, whether through fear of ostracization or from fear of retribution in the relevant press, destroyed the “market’s” ability to get to the truth.

By 1948, the popular lobotomy craze had waned, as is shown in Diefenbach’s data above, but the institutional lobotomy boom had just begun. It was tucked away in state mental hospitals, particularly in California, West Virginia, Virginia, Washington, Ohio, and New Jersey.

Jack Pressman, in Last resort: Psychosurgery and the Limits of Medicine (1998), seems to hit the nail on the head when he writes “the kinds of evaluations made as to whether psychosurgery worked would be very different in the institutional context than it was in the private practice context.”

Doctors in asylums and mental hospitals lived in a wholly different paradigm from those in for-profit medicine. Funding in asylums was based on patient count rather than medical outcome. Asylums were allowed to perform lobotomies without the consent of patients or their guardians, to whom they could refuse visitation rights.

While asylum administrators usually held medical or scientific degrees, their roles as administrators in poorly funded facilities altered their processing of the evidence on lobotomies. Asylum administrators had a stronger incentive than private practices to use lobotomies because their definitions of successful outcome were different. As Freeman wrote in a 1957 follow-up of 3000 patients, lobotomized patients “become docile and are easier to manage”. Success in the asylum was not a healthier patient, it was a less expensive patient. The promise of a patient’s being able to return to life outside the asylum was a great incentive for administrators on tight budgets. If those administrators thought lobotomy was ineffective, they would have had no reason to use it, regardless of their ethics. The clinical press had already judged it ineffective, but asylum administrators’ understanding of effectiveness was different from that of clinicians in private practice.

Pressman cites the calculus of Dr. Mesrop Tarumianz, administrator of Delaware State Hospital: “In our hospital, there are 1,250 cases and of these about 180 could be operated on for $250 per case. That will constitute a sum of $45,000 for 180 patients. Of these, we will consider that 10 percent, or 18, will die, and a minimum of 50 percent of the remaining, or 81 patients will become well enough to go home or be discharged. The remaining 81 will be much better and more easily cared for the in hospital… That will mean a savings $351,000 in a period of ten years.”

The point here is not that these administrators were monsters without compassion for their patients. The point is that significant available evidence existed to conclude that lobotomies were somewhere between bad and terrible for patients, and that this evidence was not processed by asylum administrators in the same way it was in private medical practice.

The lobotomy boom was enabled by sensationalized headlines in the popular press, tests run without control groups, ridiculously small initial sample sizes, vague and speculative language by Moniz and Freeman, cherry-picked – if not outright false – trial results, and complacence in peer review. Peer review is meaningless unless it contains some element of competition.

Some might call lobotomies a case of conflict of interest. To an extent that label fits, not so much in the sense that anyone derived much personal benefit in their official capacity, but in that the aims and interests of the involved parties – patients and clinicians – were horribly misaligned.

The roles of asylum administrators – recall that they were clinicians too – did not cause them to make bad decisions about ethics. Their roles caused and allowed them to make bad decisions about lobotomy effectiveness, which was an ethics violation because it was bad science. Different situations in different communities – private and state practices – led intelligent men, interpreting the same evidence, to reach vastly different conclusions about pounding holes in people’s faces.

It will come as no surprise to my friends that I will once again invoke Paul Feyerabend: if science is to be understood as an institution, there must be separation of science and state.

___

Epilogical fallacies

A page on the official website the Nobel prize still defends the prize awarded to Moniz. It uncritically accepts Freeman’s statistical analysis of outcomes, e.g., 2% of patients became worse after the surgery.

…

Wikipedia reports that 60% of US lobotomy patients were women. Later in the same article it reports that 40% of US lobotomies were done on gay men. Thus, per Wikipedia, 100% of US male lobotomy patients were gay. Since 18,000 of the 20,000 lobotomies done in the US were in state mental institutions, we can conclude that mental institutions in 1949-1951 overwhelmingly housed gay men. Histories of mental institutions, even those most critical of the politics of deinstitutionalization, e.g. Deinstitutionalization: A Psychiatric Titanic, do not mention gay men.

…

Elliot Valenstein, cited above, wrote in a 1987 Orlando Sentinel editorial that all the major factors that shaped the lobotomy boom are still with us today: “desperate patients and their families still are willing to risk unproven therapies… Ambitious doctors can persuade some of the media to report untested cures with anecdotal ‘research’… it could happen again.” Now let’s ask ourselves, is anything equivalent going on today, any medical fad propelled by an uncritical media and single individual or small cadre of psychiatrists, anything that has been poorly researched and might lead to disastrous outcomes? Nah.

Recent Comments