Posts Tagged climate change

Stop Orbit Change Denial Now

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science on March 31, 2016

April 1, 2016.

Just like you, I grew up knowing that, unless we destroy it, the earth would be around for another five billion years. At least I thought I knew we had a comfortable window to find a new home. That’s what the astronomical establishment led us to believe. Well it’s not true. There is a very real possibility that long before the sun goes red giant on us, instability of the multi-body gravitational dynamics at work in the solar system will wreak havoc. Some computer models show such deadly dynamism in as short as a few hundred millions years.

One outcome is that Jupiter will pull Mercury off course so that it will cross Venus’s orbit and collide with the earth. “To call this catastrophic is a gross understatement,” says Berkeley astronomer Ken Croswell. Gravitational instability might also hurl Mars from the solar system, thereby warping Earth’s orbit so badly that our planet will be ripped to shreds. If you can imagine nothing worse, hang on to your helmet. In another model, the earth itself is heaved out of orbit and we’re on a cosmic one-way journey into the blackness of interstellar space for eternity. Hasta la vista, baby.

Knowledge of the risk of orbit change isn’t new; awareness is another story. The knowledge goes right back to Isaac Newton. In 1687 Newton concluded that in a two-body system, each body attracts the other with a force (which we do not understand, but call gravity) that is proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them. That is, he gave a mathematical justification for what Keppler had merely inferred from observing the movement of planets. Newton then proposed that every body in the universe attracts every other body according to the same rule. He called it the universal law of gravitation. Newton’s law predicted how bodies would behave if only gravitational forces acted upon them. This cannot be tested in the real world, as there are no such bodies. Bodies in the universe are also affected by electromagnetism and the nuclear forces. Thus no one can test Newton’s theory precisely.

Ignoring the other forces of nature, Newton’s law plus simple math allows us to predict the future position of a two-body system given their properties at a specific time. Newton also noted, in Book 3 of his Principia, that predicting the future of a three body system was an entirely different problem. Many set out solve the so-called three-body (or generalized n-body) problem. Finally, over two hundred years later, Henri Poincaré, after first wrongly believing he had worked it out – and forfeiting the prize offered by King Oscar of Sweden for a solution – gave mathematical evidence that there can be no analytical solution to the n-body problem. The problem is in the realm of what today is called chaos theory. Even with powerful computers, rounding errors in the numbers used to calculate future paths of planets prevent conclusive results. The butterfly effect takes hold. In a computer planetary model, changing the mass of Mercury by a billionth of a percent might mean the difference between it ultimately being pulled into the sun and it’s colliding with Venus.

Too many mainstream astronomers are utterly silent on the issue of potential earth orbit change. Given that the issue of instability has been known since Poincaré, why is academia silent on the matter. Even Carl Sagan, whom I trusted in my youth, seems party to the conspiracy. In Episode 9 of Cosmos, he told us:

“Some 5 billion years from now, there will be a last perfect day on Earth. Then the sun will slowly change and the earth will die. There is only so much hydrogen fuel in the sun, and when it’s almost all converted to helium the solar interior will continue its original collapse… life will be extinguished, the oceans will evaporate and boil, and gush away to space. The sun will become a bloated red giant star filling the sky, enveloping and devouring the planets Mercury and Venus, and probably the earth as well. The inner planets will be inside the sun. But perhaps by then our descendants will have ventured somewhere else.”

He goes on to explain that we are built of star stuff, dodging the whole matter of orbital instability. But there is simply no mechanistic predictability in the solar system to ensure the earth will still be orbiting when the sun goes red-giant. As astronomer Caleb Scharf says, “the notion of the clockwork nature of the heavens now counts as one of the greatest illusions of science.” Scharf is one of the bold scientists who’s broken with the military-industrial-astronomical complex to spread the truth about earth orbit change.

But for most astronomers, there is a clear denial of the potential of earth orbit change and the resulting doomsday; and this has to stop. Let’s stand with science. It’s time to expose orbit change deniers. Add your name to the list, and join the team to call them out, one by one.

Can Science Survive?

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science, Philosophy of Science on February 16, 2016

In my last post I ended with the question of whether science in the pure sense can withstand science in the corporate, institutional, and academic senses. Here’s a bit more on the matter.

Ronald Reagan, pandering to a church group in Dallas, famously said about evolution, “Well, it is a theory. It is a scientific theory only.” (George Bush, often “quoted” as saying this, did not.) Reagan was likely ignorant of the distinction between two uses of the word, theory. On the street, “theory” means an unsettled conjecture. In science a theory – gravitation for example – is a body of ideas that explains observations and makes predictions. Reagan’s statement fueled years of appeals to teach creationism in public schools, using titles like creation science and intelligent design. While the push for creation science is usually pinned on southern evangelicals, it was UC Berkeley law professor Phillip E Johnson who brought us intelligent design.

Arkansas was a forerunner in mandating equal time for creation science. But its Act 590 of 1981 (Balanced Treatment for Creation-Science and Evolution-Science Act) was shut down a year later by McLean v. Arkansas Board of Education. Judge William Overton made philosophy of science proud with his set of demarcation criteria. Science, said Overton:

- is guided by natural law

- is explanatory by reference to natural law

- is testable against the empirical world

- holds tentative conclusions

- is falsifiable

For earlier thoughts on each of Overton’s five points, see, respectively, Isaac Newton, Adelard of Bath, Francis Bacon, Thomas Huxley, and Karl Popper.

In the late 20th century, religious fundamentalists were just one facet of hostility toward science. Science was also under attack on the political and social fronts, as well an intellectual or epistemic front.

President Eisenhower, on leaving office in 1960, gave his famous “military industrial complex” speech warning of the “danger that public policy could itself become the captive of a scientific technological elite.” At about the same time the growing anti-establishment movements – perhaps centered around Vietnam war protests – vilified science for selling out to corrupt politicians, military leaders and corporations. The ethics of science and scientists were under attack.

Also at the same time, independently, an intellectual critique of science emerged claiming that scientific knowledge necessarily contained hidden values and judgments not based in either objective observation (see Francis Bacon) or logical deduction (See Rene Descartes). French philosophers and literary critics Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida argued – nontrivially in my view – that objectivity and value-neutrality simply cannot exist; all knowledge has embedded ideology and cultural bias. Sociologists of science ( the “strong program”) were quick to agree.

This intellectual opposition to the methodological validity of science, spurred by the political hostility to the content of science, ultimately erupted as the science wars of the 1990s. To many observers, two battles yielded a decisive victory for science against its critics. The first was publication of Higher Superstition by Gross and Levitt in 1994. The second was a hoax in which Alan Sokal submitted a paper claiming that quantum gravity was a social construct along with other postmodern nonsense to a journal of cultural studies. After it was accepted and published, Sokal revealed the hoax and wrote a book denouncing sociology of science and postmodernism.

Sadly, Sokal’s book, while full of entertaining examples of the worst of postmodern critique of science, really defeats only the most feeble of science’s enemies, revealing a poor grasp of some of the subtler and more valid criticism of science. For example, the postmodernists’ point that experimentation is not exactly the same thing as observation has real consequences, something that many earlier scientists themselves – like Robert Boyle and John Herschel – had wrestled with. Likewise, Higher Superstition, in my view, falls far below what we expect from Gross and Levitt. They deal Bruno Latour a well-deserved thrashing for claiming that science is a completely irrational process, and for the metaphysical conceit of holding that his own ideas on scientific behavior are fact while scientists’ claims about nature are not. But beyond that, Gross and Levitt reveal surprisingly poor knowledge of history and philosophy of science. They think Feyerabend is anti-science, they grossly misread Rorty, and waste time on a lot of strawmen.

Following closely on the postmodern critique of science were the sociologists pursuing the social science of science. Their findings: it is not objectivity or method that delivers the outcome of science. In fact it is the interests of all scientists except social scientists that govern the output of scientific inquiry. This branch of Science and Technology Studies (STS), led by David Bloor at Edinburgh in the late 70s, overplayed both the underdetermination of theory by evidence and the concept of value-laden theories. These scientists also failed to see the irony of claiming a privileged position on the untenability of privileged positions in science. I.e., it is an absolute truth that there are no absolute truths.

While postmodern critique of science and facile politics in STC studies seem to be having a minor revival, the threats to real science from sociology, literary criticism and anthropology (I don’t mean that all sociology and anthropology are non-scientific) are small. But more subtle and possibly more ruinous threats to science may exist; and they come partly from within.

Modern threats to science seem more related to Eisenhower’s concerns than to the postmodernists. While Ike worried about the influence the US military had over corporations and universities (see the highly nuanced history of James Conant, Harvard President and chair of the National Defense Research Committee), Eisenhower’s concern dealt not with the validity of scientific knowledge but with the influence of values and biases on both the subjects of research and on the conclusions reached therein. Science, when biased enough, becomes bad science, even when scientists don’t fudge the data.

Pharmaceutical research is the present poster child of biased science. Accusations take the form of claims that GlaxoSmithKline knew that Helicobacter pylori caused ulcers – not stress and spicy food – but concealed that knowledge to preserve sales of the blockbuster drugs, Zantac and Tagamet. Analysis of those claims over the past twenty years shows them to be largely unsupported. But it seems naïve to deny that years of pharmaceutical companies’ mailings may have contributed to the premature dismissal by MDs and researchers of the possibility that bacteria could in fact thrive in the stomach’s acid environment. But while Big Pharma may have some tidying up to do, its opponents need to learn what a virus is and how vaccines work.

Pharmaceutical firms generally admit that bias, unconscious and of the selection and confirmation sort – motivated reasoning – is a problem. Amgen scientists recently tried to reproduce results considered landmarks in basic cancer research to study why clinical trials in oncology have such high failure rate. They reported in Nature that they were able to reproduce the original results in only six of 53 studies. A similar team at Bayer reported that only about 25% of published preclinical studies could be reproduced. That the big players publish analyses of bias in their own field suggests that the concept of self-correction in science is at least somewhat valid, even in cut-throat corporate science.

Some see another source of bad pharmaceutical science as the almost religious adherence to the 5% (+- 1.96 sigma) definition of statistical significance, probably traceable to RA Fisher’s 1926 The Arrangement of Field Experiments. The 5% false-positive probability criterion is arbitrary, but is institutionalized. It can be seen as a classic case of subjectivity being perceived as objectivity because of arbitrary precision. Repeat any experiment long enough and you’ll get statistically significant results within that experiment. Pharma firms now aim to prevent such bias by participating in a registration process that requires researchers to publish findings, good, bad or inconclusive.

Academic research should take note. As is often reported, the dependence of publishing on tenure and academic prestige has taken a toll (“publish or perish”). Publishers like dramatic and conclusive findings, so there’s a strong incentive to publish impressive results – too strong. Competitive pressure on 2nd tier publishers leads to their publishing poor or even fraudulent study results. Those publishers select lax reviewers, incapable of or unwilling to dispute authors. Karl Popper’s falsification model of scientific behavior, in this scenario, is a poor match for actual behavior in science. The situation has led to hoaxes like Sokal’s, but within – rather than across – disciplines. Publication of the nonsensical “Fuzzy”, Homogeneous Configurations by Marge Simpson and Edna Krabappel (cartoon character names) by the Journal of Computational Intelligence and Electronic Systems in 2014 is a popular example. Following Alan Sokal’s line of argument, should we declare the discipline of computational intelligence to be pseudoscience on this evidence?

Note that here we’re really using Bruno Latour’s definition of science – what scientists and related parties do with a body of knowledge in a network, rather than simply the body of knowledge. Should scientists be held responsible for what corporations and politicians do with their knowledge? It’s complicated. When does flawed science become bad science. It’s hard to draw the line; but does that mean no line needs to be drawn?

Environmental science, I would argue, is some of the worst science passing for genuine these days. Most of it exists to fill political and ideological roles. The Bush administration pressured scientists to suppress communications on climate change and to remove the terms “global warming” and “climate change” from publications. In 2005 Rick Piltz resigned from the U.S. Climate Change Science Program claiming that Bush appointee Philip Cooney had personally altered US climate change documents to lessen the strength of their conclusions. In a later congressional hearing, Cooney confirmed having done this. Was this bad science, or just bad politics? Was it bad science for those whose conclusions had been altered not to blow the whistle?

The science of climate advocacy looks equally bad. Lack of scientific rigor in the IPCC is appalling – for reasons far deeper than the hockey stick debate. Given that the IPCC started with the assertion that climate change is anthropogenic and then sought confirming evidence, it is not surprising that the evidence it has accumulated supports the assertion. Compelling climate models, like that of Rick Muller at UC Berkeley, have since given strong support for anthropogenic warming. That gives great support for the anthropogenic warming hypothesis; but gives no support for the IPCC’s scientific practices. Unjustified belief, true or false, is not science.

Climate change advocates, many of whom are credentialed scientists, are particularly prone to a mixing bad science with bad philosophy, as when evidence for anthropogenic warming is presented as confirming the hypothesis that wind and solar power will reverse global warming. Stanford’s Mark Jacobson, a pernicious proponent of such activism, does immeasurable damage to his own stated cause with his descent into the renewables fantasy.

Finally, both major climate factions stoop to tying their entire positions to the proposition that climate change has been measured (or not). That is, both sides are in implicit agreement that if no climate change has occurred, then the whole matter of anthropogenic climate-change risk can be put to bed. As a risk man observing the risk vector’s probability/severity axes – and as someone who buys fire insurance though he has a brick house – I think our science dollars might be better spent on mitigation efforts that stand a chance of being effective rather than on 1) winning a debate about temperature change in recent years, or 2) appeasing romantic ideologues with “alternative” energy schemes.

Science survived Abe Lincoln (rain follows the plow), Ronald Reagan (evolution just a theory) and George Bush (coercion of scientists). It will survive Barack Obama (persecution of deniers) and Jerry Brown and Al Gore (science vs. pronouncements). It will survive big pharma, cold fusion, superluminal neutrinos, Mark Jacobson, Brian Greene, and the Stanford propaganda machine. Science will survive bad science because bad science is part of science, and always has been. As Paul Feyerabend noted, Galileo routinely used propaganda, unfair rhetoric, and arguments he knew were invalid to advance his worldview.

Theory on which no evidence can bear is religion. Theory that is indifferent to evidence is often politics. Granting Bloor, for sake of argument, that all theory is value-laden, and granting Kuhn, for sake of argument, that all observation is theory-laden, science still seems to have an uncanny knack for getting the world right. Planes fly, quantum tunneling makes DVD players work, and vaccines prevent polio. The self-corrective nature of science appears to withstand cranks, frauds, presidents, CEOs, generals and professors. As Carl Sagan Often said, science should withstand vigorous skepticism. Further, science requires skepticism and should welcome it, both from within and from irksome sociologists.

.

.

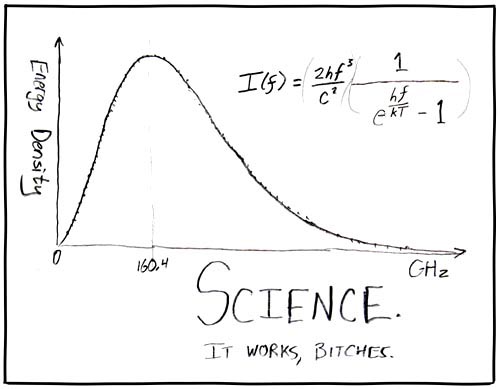

XKCD cartoon courtesy of xkcd.com

Science, God, and the White House

Posted by Bill Storage in Philosophy of Science on January 9, 2016

Back in the 80s I stumbled upon the book, Scientific Proof of the Existence of God Will Soon Be Announced by the White House!, by Franklin Jones, aka Frederick Jenkins, later Da Free John, later Adi Da Samraj. I bought it on the spot. Likely a typical 70s mystic charlatan, Jones nonetheless saw clearly our poor grasp of tools for seeking truth and saw how deep and misguided is our deference to authority. At least that’s how I took it.

Who’d expect a hippie mystic to be a keen philosopher of science. The book’s title, connecting science, church and state, shrewdly wraps four challenging ideas:

- That there can be such a thing as scientific proof of anything

- That there could be new findings about the existence of God

- That evidence for God could be in the realm of science

- That government should or could accredit a scientific theory

On the first point, few but the uneducated, TIME magazine, and the FDA think that proof is in the domain of science. Proof is deductive. It belongs to math, logic and analytic philosophy. Science uses evidence and induction to make inferences to the best explanation.

Accepting that strong evidence would suffice as proof, point number 2 is a bit trickier. Evidence of God’s existence can’t be ruled out a priori. God could be observable or detectable; we might see him or his consequences. An almighty god could easily have chosen to regularly show himself or to present unambiguous evidence. But Yahweh, at least in modern times, doesn’t play like that (A wicked and adulterous generation demands a sign but none will be given – Matthew 16:4). While believers often say no evidence would satisfy the atheist, I think a focused team could come up with rules for a demonstration that at least some nonbelievers would accept as sufficient evidence.

Barring any new observations that would constitute evidence, point number 3 is tough to tackle without wading deep into philosophy of science. To see why, consider the theory that God exists. Is it even a candidate for a scientific theory, as one WSJ writer thinks (Science Increasingly Makes the Case for God)? I.e., is it the content of a theory or the way it is handled by its advocates that makes the theory scientific? If the latter, it can be surprisingly hard to draw the line between scientific investigations and philosophical ones. Few scientists admit this line is so blurred, but how do string theorists, who make no confirmable or falsifiable predictions, defend that they are scientists? Their fondness for non-empirical theory confirmation puts them squarely in the ranks of the enlightenment empiricist, Bishop Berkeley of Cloyne (namesake of our fair university) who maintained that matter does not exist. Further, do social scientists make falsifiable predictions, or do they just continually adjust their theory to accommodate disconfirming evidence?

That aside, those who work in the God-theory space somehow just don’t seem to qualify as scientific – even the young-earth creationists trained in biology and geology. Their primary theory doesn’t seem to generate research and secondary theories to confirm or falsify. Their papers are aimed at the public, not peers – and mainly aim at disproving evolution. Can a scientific theory be primarily negative? Could plate-tectonics-is-wrong count as a proper scientific endeavor?

Gould held that God was simply outside the realm of science. But if we accept that the existence of God could be a valid topic of science, is it a good theory? Following Karl Popper, a scientific theory can withstand only a few false predictions. On that view the repeated failures of end-of-days predictions by Harold Camping and Herbert Armstrong might be sufficient to kill the theory of God’s existence. Or does their predictive failures simply exclude them from the community of competent practitioners?

Would NASA engineer, Edgar Whisenant be more credible at making predictions based on the theory of God’s existence? All his predictions of rapture also failed. He was accepted by the relevant community (“…in paradigm choice there is no standard higher than the assent of the relevant community” – Thomas Kuhn) since the Trinity Broadcast Network interrupted its normal programming to help watchers prepare. If a NASA engineer has insufficient scientific clout, how about our first scientist? Isaac Newton predicted, in Observations upon the Prophecies of Daniel and the Apocalypse of St. John, that the end would come in 2000 CE. Maybe Newton’s calculator had the millennium bug.

If we can’t reject the theory for any number of wrong predictions, might there be another basis for rejecting it? Some say absence of a clear mechanism is a good reason to reject theories. In the God theory, no one seems to have proposed a mechanism by which such a God could have arisen. Aquinas’s tortured teleology and Anselm’s ontological arguments still fail on this count. But it seems unfair to dismiss the theory of God’s existence on grounds of no clear mechanism, because we have long tolerated other theories deemed scientific with the same weakness. Gravity, for example.

Does assent of the relevant community grant scientific status to a theory, as Kuhn would have it? If so, who decides which community is the right one? Theologians spend far more time on Armageddon than do biologists and astrophysicists – and theologians are credentialed by their institutions. So why should Hawking and Dawkins get much air time on the matter? Once we’ve identified a relevant community, who gets to participate in its consensus?

This draws in point number 4, above. Should government or the White House have any more claim to a scientific pronouncement than the Council of Bishops? If not, what are we to think of the pronouncements by Al Gore and Jerry Brown that the science of climate is settled? Should they have more clout on the matter than Pope Francis (who, interestingly, has now made similar pronouncements)?

If God is outside the realm of science, should science be outside the jurisdiction of government? What do we make of President Obama’s endorsement of “calling out climate change deniers, one by one”? You don’t have to be Franklin Jones or Da Free John to see signs here of government using the tools of religion (persecution, systematic effort to censure and alienate dissenters) in the name of science. Is it a stretch to see a connection to Jean Bodin, late 16th century French jurist, who argued that only witches deny the existence of witches?

Can you make a meaningful distinction between our government’s pronouncements on the truth or settledness of the climate theory (as opposed to government’s role in addressing it) and the Kremlin’s 1948 pronouncement that only Lamarckian inheritance would be taught, and their call for all geneticists to denounce Mendelian inheritance? Is it scientific behavior for a majority in a relevant community to coerce dissenters?

In trying to draw a distinction between UN and US coercion on climate science and Lysenkoism, some might offer that we (we moderns or we Americans) are somehow different – that only under regimes like Lenin’s and Hitler’s does science get so distorted. In thinking this, it’s probably good to remember that Hitler’s eugenics was born right here, and flourished in the 20th century. It had nearly full academic support in America, including Stanford and Harvard. That is, to use Al Gore’s words, the science was settled. California, always a trendsetter, by the early 1920s, claimed 80% of America’s forced sterilizations. Charles Goethe, founder of Sacramento State University, after visiting Hitler’s Germany in 1934 bragged to a fellow California eugenicist about their program’s influence on Hitler.

If the era of eugenics seems too distant to be relevant to the issue of climate science/politics, consider that living Stanford scientist, Paul Ehrlich, who endorsed compulsory abortion in the 70s, has had a foot in both camps.

As crackpots go, Da Free John was rather harmless.

________

“Indeed, it has been concluded that compulsory population-control laws, even including laws requiring compulsory abortion, could be sustained under the existing Constitution if the population crisis became sufficiently severe to endanger the society.” – Ehrlich, Holdren and Ehrlich, EcoScience, 3rd edn, 1977, p. 837

“You will be interested to know that your work has played a powerful part in shaping the opinions of the group of intellectuals who are behind Hitler in this epoch-making program.” – Charles Goethe, letter to Edwin Black, 1934

But You Need the Data

Posted by Bill Storage in Multidisciplinarians on January 4, 2016

In my last post, But We Need the Rain, I suggested that environmentalist animism in San Francisco may fill the role once filled by religious belief, and may suffuse daily life as Christian belief did in medieval Europe. As the phrase “God be with ye” once reminded countrymen of correct thinking, so too might acknowledgment that we need the rain.

Medieval institutions – social and governmental – exerted constant pressure steering people away from wrong thinking; and the church dissuaded its flock from asking the wrong questions. Telling a lie to save a soul was OK; deceiving heathens into Christianity was just fine. I wonder if a weaker form of this sentiment remains in my fair city – in the form of failing to mention relevant facts about an issue and through the use of deceptive and selective truths. As theologian Thomas Burnet put it in the early 18th century, too much light is hurtful to weak eyes.

The San Francisco Chronicle, according to Google data, has published over 50 articles in the last two years mentioning the Shasta and Oroville reservoirs in connection with California’s four-year-old drought. Many of these pieces call attention to low levels of these reservoirs, e.g., Shasta was at 53% of normal level in January 2014.

None mention that Shasta and Oroville were, despite the drought, at 108% and 101% of normal level in April 2013, two years into the drought. Climate is mentioned in nearly all sfgate.com articles on the drought, but mismanagement of water resources by governments is mentioned in only one. Digging a bit deeper – with other sources – you’ll find bitter disputes between farmers saying water is wasted on environmental restoration and environmentalists asking why desert farmers want to grow thirsty crops like rice and cotton. I’d think Northern California citizens, asked by the governor to bathe less, might be interested in why so much of the Shasta and Oroville water left the reservoirs – whether they want to blame Sacramento, farmers, or environmentalists – and in the details of the dispute.

Is the Chronicle part of a conspiracy to get liberals in power by linking the water shortage to climate change rather than poor governance? I doubt it. There are no conservatives to displace. More likely, it seems to me, the Chronicle simply mirrors the values and beliefs held by its readers, an unusually monolithic community with a strong uniformity of views. The sense of identification with a community here somewhat resembles that of a religious group, where there’s a tendency for beliefs to be held as true by individuals because they are widely believed by the group – and to select or reject evidence based on whether it supports a preexisting belief.

“Being crafty, I caught you with guile.” – 2 Corinthians, 12:16

But We Need the Rain

Posted by Bill Storage in Multidisciplinarians on January 1, 2016

Chance outdoor meetings on recent damp days in San Francisco tend to start or finish (or both) with the statement, “but we need the rain.” No information is conveyed by these words. Their recipient already knows we need the rain. And the speaker knows the recipient knows it. Perhaps it is said aloud to be sure the nature gods hear it and continue to pour forth the blessings. Perhaps it reveals competitive piety – a race to first claim awareness of our climate-change sins. Or maybe it has just become a pleasant closing of a street encounter along the lines of “good bye.”

Of course, we don’t need the rain. San Francisco’s water supply falls 200 miles east of here and is collected in Hetch Hetchy Reservoir, eternally under attack from activists who insist their motive is environmental restoration, not anti-capitalism. We don’t pump water that falls at sea level up into our reservoirs, nor do we collect water that falls on the coast. A coastal system that dumps rain in San Francisco does not mean it’s raining in the Sierras.

So California’s High Sierras need the rain, not us. But saying “but we need the rain” does little harm. Saying it lets the gods know we are grateful; and saying it reminds each other to be thankful.

“We need the rain” may have more in common with “good bye” than is apparent to most. Etymologists tell us that “God be with ye” became “God b’wy” by the mid-1600s, and a few decades later was “good b’wy,” well on its way to our “good bye,” which retains the ending “ye” as a reminder of its genesis

In the homogenous cultures of pre-enlightenment Europe, God was a fact of the world, not a belief of religion. “God be with ye” wasn’t seen as a religious sentiment. It was an expression of hopefulness about a universe that was powered by God almighty, the first cause and prime mover, who might just be a providential God hearing our pleas that He be with ye. Am I overly cynical in seeing a connection?

Rain be with ye.

Mark Jacobson’s Science

Posted by Bill Storage in Sustainable Energy on June 22, 2015

The writings of Stanford’s Mark Jacobson effortlessly blends science and ideology along a continuum to envision an all-renewable energy future for America. His success in doing this marks a sad state of affairs between science, culture and politics.

Jacobson’s popularity began with his 2009 Scientific American piece, A Plan to Power 100 Percent of the Planet with Renewables. The piece and his recent works argue both a means by which we could transition to renewable-only power and that an all-renewable energy mix is the means by which we should pursue greenhouse gas reduction. They seem to answer several questions, though the questions aren’t stated explicitly:

Is it possible to power 100% of the planet with renewables?

Is it feasible to power 100% of the planet with renewables?

Is it desirable to power 100% of the planet with renewables?

Is a renewable-only portfolio the best means of stopping the increase in atmospheric CO2?

The first question is an engineering problem. The 2nd is an engineering and economic question. The 3rd is economic, social, and political. The 4th is my restating of the 3rd to emphasize an a-priori exclusion of non-renewables from the goal of stopping the increase in atmospheric CO2. That objective, implied in the Sci Am article’s title, is explicitly stated in the piece’s opening paragraph:

“In December leaders from around the world will meet in Copenhagen to try to agree on cutting back greenhouse gas emissions for decades to come. The most effective step to implement that goal would be a massive shift away from fossil fuels to clean, renewable energy sources.”

It should be clear to readers that the possibility or technical feasibility of a global 100%-renewable energy portfolio in no way defends the assertion that it the most effective way to implement that goal is such a portfolio. Assuming that the most desirable way to cut greenhouse gas emissions is by using a 100% renewable portfolio, the feasibility of such a portfolio becomes an engineering, economic, and social challenge; but that is not the gist of Jacobson’s works, where the premise and conclusion are intertwined. Questions 1 and 2 would obviously be great topics for a paper, as would questions 3 and 4. Addressing all of them together is a laudable goal – and one that requires clear thinking about evidence and justification. On that requirement, A Plan to Power 100 Percent of the Planet with Renewables fails outright in my view, as do his recent writings.

Major deficiencies in Jacobson’s engineering and economic analyses have been discussed at length, most notably by Brian Wang, William Hannahan, Ted Trainer, Edward Dodge, Nate Gilbraith, Charles Barton, Gene Preston, and Barry W. Brook. The deficiencies they address include wrong facts, adverse selection, and vague language, e.g.:

“In another study, when 19 geographically disperse wind sites in the Midwest, over a region 850 km 850 km, were hypothetically interconnected, about 33% of yearly averaged wind power was calculated to be usable at the same reliability as a coal-fired power plant.”

Engineers will note that “usable at the same reliability” simply cannot be parsed into an intelligible claim; and if the intent was to say that that these sites had the same capacity factor as a coal-powered plant, the statement is obviously false.

Jacobson’s proposal for New York includes clearing 340 square miles of land to generate 39,000 MW with concentrated solar power facilities. CSP requires flat, sunny, unburdened land, kept free or rain and snow without addressing the possibility, let alone feasibility, of doing this. His NY plan calls for building 140 sq mi of photovoltaic farms, with similar requirements for land quality. He overstates capacity factor of both wind and photovoltaics in NY, as elsewhere. He calls for 12,500 5MW offshore wind turbines with no discussion of feasibility in light of bathymetry, shipping and commercial water route use. Further, his offshore wind turbine plan ignores efficiency reductions due to wind shadowing that would exist in his proposed turbine density. The economic impact, social acceptability, and environmental impact of clearing hundreds of square miles of mostly-wooded land and grading it level (NY is hilly), of erecting another 4000 onshore turbines, and of 12,500 offshore turbines is a very real – but unaddressed by Jacobson – factor in determining the true feasibility of the proposed solution.

The above writers cover many concerns about Jacobson’s work along these lines. Their criticism is aimed at the feasibility of Jacobson’s implementation plan. In my engineering judgment these complaints have considerable merit. But that is not where I want to go here. Instead, I’m intensely concerned about two related issues:

1) the lack of knowledge on the street that Jacobson has credible opponents that dispute his major claims

2) absence of criticism of Jacobson for doing bad science – not bad because of wrong details but bad because of poor method and bad values.

By values, I don’t mean ethics, beliefs or preferences. Jacobson and I share social values (cut CO2 emissions) but not scientific values. By scientific values I mean things like accuracy, precision, clarity (e.g., “useable at the same reliability”), testability, and justification – epistemic values focused on reliable knowledge. To clarify, I’m not so naïve as to think scientists and engineers shouldn’t have biases and personal beliefs, that they shouldn’t act on hunches, or that theory and observation are not intertwined. But misrepresenting normative statements as descriptive ones is a kind of bad science against which Bacon and Descartes would have railed; and that is what Jacobson has done. He answered one question (what we should do to level CO2 emissions) while pretending to answer a different one (are renewables sufficient to replace fossil fuels). This should not pass as science.

Jacobson’s writings are highly quantitative where they oppose fission, and grossly qualitative where they dodge the deficiencies in renewables. This holds particularly true on the matters of variability of renewables (e.g., large regions of Europe are often simultaneously without wind and sun), difficulties and inefficiencies of distribution, and the feasibility of energy storage and its inevitable inefficiencies (I mean laws-of-nature inefficiencies, not inefficiencies that can be cured with technology). He states the fission is not carbon-free because fossil fuels are used in its construction and maintenance, while failing to mention that the concrete and other CO2-emitters used in building and maintaining solar and wind power dwarf those of fission.

At times Jacobson’s claims might be called crypto-normative. For example, he says that “Nuclear power results in up to 25 times more carbon emissions than wind energy, when reactor construction and uranium refining and transport are considered.” As stated, the claim is absurd. Applying the principle of charity in argument, I dug down to see what he might have meant to say. Beneath it, he is actually including the CO2 footprint of his estimation of the impact of inevitable nuclear war. So, yes, with a big enough nuclear war included (not uranium refining and transport), the CO2 emissions of nuclear power plus nuclear war could result in up to 25 times more CO2 than wind. But why stop there? We could conceive of nuclear war (or non-nuclear was for that matter) that emitted thousands of time more CO2 than wind power. Speculation about nuclear war risks is a worthwhile topic, but not when buried in the calculation of CO2 footprints. And it has no place in calculating the most effective means to cut greenhouse gas.

How can Jacobson have so many mistakes in his details (all of which favor an all-renewables plan) and engage in such bad science while so few seem to notice? I’m not sure, but I fear that much of science has become the handmaid of politics and naïve ideological activism. I cannot know Jacobson’s motives, but I am certain of the incentives. Opposition to renewables is framed as opposing the need to cut CO2 and worse – like being in the pocket of evil corporations. I experience this personally, when I attend clean-tech events and when I use this example Philosophy of Science talks. As a career and popularity move, it’s hard to go wrong by jumping on the renewables-only bandwagon.

At a recent Silicon Valley clean-tech event, I challenged three different attendees on claims they made about renewables. Two of these were related to capacity factors given for solar power on the east coast and one dealt with the imminence (or lack thereof) of utility-scale energy storage technology. All three attendees, independently, in their responses cited Mark Jacobson’s work as justification for their claims. My attempts at reality checks on capacity factors using real-world values in calculations didn’t seem to faze them. Arguments hardly affect the faithful, noted Paul Feyerabend; their beliefs have an entirely different foundation.

Science was once accused of being the handmaid of religion. Under President Eisenhower, academic science was accused of being a pawn of the military industrial complex and then took big steps to avoid being one. The money flow is now different, but the incentives for institutional science – where it comes anywhere near policy matters – to conform to fickle societal expectations present a huge obstacle to the honest pursuit of a real CO2 solution.

I’m not sure how to fix the problem demonstrated by the unquestioning acceptance of Jacobson’s work as scientific knowledge. Improvements in STEM education will certainly help. But I doubt that spreading science and engineering education across a broader segment of society will be sufficient. It seems to me we’d benefit more from having engineers and policy makers develop a broader interpretation of the word science – one that includes epistemology and theory of justification. I’ve opined in the past that teaching philosophy of science to engineers would make them much better at engineering. It would also result in better policy makers in a world where technology has become integral to everything. Independent of whether a statement is true or false, every educated person should be able to differentiate a scientific statement from a non-scientific one, should know what constitutes confirming and disconfirming evidence, and should cry foul when a normative claim pretends to be descriptive.

“The separation of state and church must be complemented by the separation of state and science, that most recent, most aggressive, and most dogmatic religious institution.” – Paul Feyerabend – Against Method, 1975.

“I tried hard to balance the needs of the science and the IPCC, which were not always the same.” – Keith Briffa – IPCC email correspondence, 2007.

“A philosopher who has been long attached to a favorite hypothesis, and especially if he have distinguished himself by his ingenuity in discovering or pursuing it, will not, sometimes, be convinced of its falsity by the plainest evidence of fact. Thus both himself, and his followers, are put upon false pursuits, and seem determined to warp the whole course of nature, to suit their manner of conceiving of its operations.” – Joseph Priestley – The History and Present State of Electricity, 1775

Sun Follows the Solar Car

Posted by Bill Storage in Engineering, Sustainable Energy on January 25, 2014

Bill Storage once got an A in high school Physics and suggests no further credentials are needed to evaluate the claims of most eco-fraud.

Once a great debate raged in America over the matter of whether man-mad climate change had occurred. Most Americans believed that it had. There were theories, models, government-sponsored studies, and various factions arguing with religious fervor. The time was 1880 and the subject was whether rain followed the plow – whether the westward expansion of American settlers beyond the 100th meridian had caused an increase in rain that would make agricultural life possible in the west. When the relentless droughts of the 1890s offered conflicting evidence, the belief died off, leavings its adherents embarrassed for having taken part in a mass delusion.

We now know the dramatic greening of the west from 1845 to 1880 was due to weather, not climate. It was not brought on by Mormon settlements, vigorous tilling, or the vast amounts of dynamite blown off to raise dust around which clouds could form. There was a shred of scientific basis for the belief; but the scale was way off.

We now know the dramatic greening of the west from 1845 to 1880 was due to weather, not climate. It was not brought on by Mormon settlements, vigorous tilling, or the vast amounts of dynamite blown off to raise dust around which clouds could form. There was a shred of scientific basis for the belief; but the scale was way off.

It seems that the shred of science was not really a key component of the widespread belief that rain would follow the plow. More important was human myth-making and the madness of crowds. People got swept up in it. As ancient Jewish and Roman writings show, public optimism and pessimism ebbs and flows across decades. People confuse the relationship between man and nature. They either take undue blame or undo credit for processes beyond their influence, or they assign their blunders to implacable cosmic forces. The period of the Western Movement was buoyant, across political views and religions. Some modern writers force-fit the widely held belief about rain following the plow in the 1870s into the doctrine of Manifest Destiny. These embarrassing beliefs were in harmony, but were not tied genetically. In other words, don’t blame the myth that rain followed the plow on the Christian right.

Looking back, one wonders how farmers, investors and politicians, possibly including Abraham Lincoln, could so deeply indulge in belief held on irrational grounds rather than evidence and science. Do modern humans do the same? I’ll vote yes.

Today’s anthropogenic climate theories have a great deal more scientific basis than those of the 1870s. But many of our efforts at climate cure do not. Blame shameless greed for some of the greenwashing; but corporations wouldn’t waste their time if consumers weren’t willing to waste their dollars and hopes.

Take Ford’s solar-powered hybrid car, about which a SmartPlanet writer recently said:

Imagine an electric car that can charge without being plugged into an outlet and without using electricity from dirty energy sources, like coal.

He goes on to report that Ford plans to experiment with such a solar-hybrid concept car having a 620-mile range. I suspect many readers will understand that experimentation to mean experimenting in the science sense rather than in the marketability sense. Likewise I’m guessing many readers will allow themselves to believe that such a car might derive a significant part of the energy used in a 620-mile run from solar cells.

We can be 100% sure that Ford is not now experimenting on – nor will ever experiment on – a solar-powered car that will get a significant portion of its energy from solar cells. It’s impossible now, and always will be. No technology breakthrough can alter the laws of nature. Only so much solar energy hits the top of a car. Even if you collected every photon of it, which is again impossible because of other laws of physics, you couldn’t drive a car very far on it.

Most people – I’d guess – learned as much in high school science. Those who didn’t might ask themselves, based on common sense and perhaps seeing the size of solar panels needed to power a telephone in the desert, if a solar car seems reasonable.

The EPA reports that all-electric cars like the Leaf and Tesla S get about 3 miles per kilowatt-hour of energy. The top of a car is about 25 square feet. At noon on June 21st in Phoenix, a hypothetically perfect, spotless car-top solar panel could in theory generate 30 watts per square foot. You could therefore power half of a standard 1500 watt toaster with that car-top solar panel. If you drove your car in the summer desert sun for 6 hours and the noon sun magically followed it into the shade and into your garage – like rain following the plow – you could accumulate 4500 watt-hours (4.5 kilowatt hours) of energy, on which you could drive 13.5 miles, using the EPA’s numbers. But experience shows that 30 watts per square foot is ridiculously optimistic. Germany’s famous solar parks, for example, average less than one watt per square foot; their output is a few percent of my perpetual-noon-Arizona example. Where you live, it probably doesn’t stay noon, and you’re likely somewhat north of Phoenix, where the sun is far closer to the horizon, and it’s not June 21st all year (hint: sine of 35 degrees times x, assuming it’s not dark). Oh, and then there’s clouds. If you live in Bavaria or Cleveland, or if your car roof’s dirty – well, your mileage may vary.

Recall that this rather dim picture cannot be made much brighter by technology. Physical limits restrict the size of the car-top solar panel, nature limits the amount of sun that hits it, and the Shockley–Queisser limit caps the conversion efficiency of solar cells.

Curbing CO2 emissions is not a lost cause. We can apply real engineering to the problem. Solar panels on cars isn’t real engineering; it’s pandering to public belief. What would Henry Ford think?

—————————-

.

Tom Hight is my name, an old bachelor I am,

You’ll find me out West in the country of fame,

You’ll find me out West on an elegant plain,

And starving to death on my government claim.

Hurrah for Greer County!

The land of the free,

The land of the bed-bug,

Grass-hopper and flea;

I’ll sing of its praises

And tell of its fame,

While starving to death

On my government claim.

Opening lyrics to a folk song by Daniel Kelley, late 1800s

Engineering Innovation, Environmentalism and Sustainable Energy

Posted by Bill Storage in Engineering, Sustainable Energy on October 16, 2012

If the world is to be saved, it will be innovative engineers who save it.

If the world is to be saved, it will be innovative engineers who save it.

There is a reasonable chance that the planet needs saving from greenhouse gas and too much carbon dioxide. It’s not certain, and the climate models have far more flaws than many admit (Trenberth’s missing heat, the missing carbon sink, etc.). But the case for global warming is plausible and credible. It’s foolish to try to quantify the likelihood of climate catastrophe; but the model’s credibility and its level of peer review is sufficient to warrant grave concern and immediate work.

Environmental activists, scientists and politicians have made real progress on the climate problem. Calamatists and deniers might not see it that way, because that progress has been by fits and starts. It has involved bitter ideological disputes, ugly politics, and money spent on absurd tangents and scams. But such is the path of progress in a democratic system; and no one has yet to find a better means of agreeing on how to live together.

Environmentalists are opinionated, irrational, pessimistic, Luddite ideologues, unwilling to change their minds or their methods despite evidence. At least that’s how their opponents see them. But national parks, low-emissions cars, lead-free paint, and elimination of chlorofluorocarbons have served us all rather well with acceptable costs; and noisy environmentalists can take much of the credit. It is hard to argue (though some have) that we aren’t better off as a result of the 1970 Clean Air Act. Environmental activism has been innovative and entrepreneurial. Bold individuals and grass-roots movements did their work by being disruptive. They sought and received investment, more in publicity than in money, from high profile Hollywood entertainers. They attached brands, like Jane Fonda, to their polemical products with great success. Richard Posner calls non-academic moralists like Rosa Parks and Susan B Anthony “moral entrepreneurs.” That term seems equally applicable to much of the environmental movement.

Environmentalism, packed with emotion and persuasive passion, is a fine tool for raising awareness. It has been wildly successful; and the word is out. Environmentalism is, however, an extremely poor tool for problem solving. Unfortunately, much of the environmental movement seems unaware of this limitation. It’s time for the engineers.

Scientists have done – and will continue to do – great work in climate modeling, energy research, and geoengineering theory. They’ve shown that global warming could disrupt ocean currents causing a new ice age, that synthetic algae biofuel warrants serious study, and that direct manipulation of climate – if you look far enough into the future – is not only possible but inevitable. Man-made or not, the earth’s climate will do something very unpleasant in the next 50,000 years and humans will likely choose climate engineering over extinction. Scientists will define the mechanism for doing this; engineers will translate concepts into technology. It will be scientists who demonstrate inertial confinement fusion but it will be engineers and innovators who make it utility scale.

Scientists have done – and will continue to do – great work in climate modeling, energy research, and geoengineering theory. They’ve shown that global warming could disrupt ocean currents causing a new ice age, that synthetic algae biofuel warrants serious study, and that direct manipulation of climate – if you look far enough into the future – is not only possible but inevitable. Man-made or not, the earth’s climate will do something very unpleasant in the next 50,000 years and humans will likely choose climate engineering over extinction. Scientists will define the mechanism for doing this; engineers will translate concepts into technology. It will be scientists who demonstrate inertial confinement fusion but it will be engineers and innovators who make it utility scale.

Ozzie Zehner, author of Green Illusions, correctly observes that America has an alternative energy fetish. While walkable neighborhoods, conservation and home insulation get little press, solar power is everyone’s darling. The lens of technology is focused almost exclusively on a single cure for our energy problems: produce more energy. But the energy crisis can also be seen as cultural rather than technological. History gives evidence that increases in production and consumption efficiency lead to more consumption (Jevons Paradox). Ozzie proposes that better designed communities, reproductive rights, efficiency codes, insulation, and dwellings designed for sensible passive solar energy have great leverage since they address demand rather than supply.

In Green Illusions Ozzie is neither anti-capitalism nor anti-technology. Some of his proposals involve behavior change and others call for innovative design and engineering aimed at reducing energy demand. On the former, I’m not convinced that enough behavior change can happen in the time needed to seriously impact CO2 output. But I’m very optimistic about the potential for technology and capitalism to save us, Jevons Paradox and all, and despite claims that technology and capitalism are the roots of evil.

The present increasing disruption of the global environment is the product of a dynamic technology and science which were originating in the Western medieval world against which Saint Francis was rebelling in so original a way. – Lynn White, Jr, “The Historical Roots of Our Ecological Crisis”

Let’s change the system and then we’ll begin to change the climate and save the world. The destructive model of capitalism is eradicating life. – Hugo Chavez at the Dec. 2009 UN Climate Change Conf.

The environmental movement now seems far more interested in mutual confirmation of their moral superiority than on fixing things. Far too many environmental moral-entrepreneurs have let their fight take them to an ideological – perhaps religious – place where they dwell on ecological sin and atonement, and revel in the prospect that things are going to hell fast. Since it was technology, capitalism and Christian ethics that got us in this environmental mess, we need to reject the whole lot; and they certainly can’t be part of the cure… Not so fast.

The big variables in the CO2 game are population, per-capita energy use, device efficiency and production efficiency. Despite their local success, our moral entrepreneurs have had little effect on awareness and behavior change outside Europe and America, the so-called global north. The parts of the world just now creeping out of poverty have other priorities; per-capita usage and device efficiency will likely be driven more by economics than by morality. China, for example, now adds roughly one gigawatt of coal-based electricity generation every week. It has made it clear that no climate-related restrictions will impede its growth. And China exports about 99% of the solar panels they produce. If we cut US CO2 output to zero, it would amount to only a minor delay in the timing of any impending global warming catastrophe.

The big variables in the CO2 game are population, per-capita energy use, device efficiency and production efficiency. Despite their local success, our moral entrepreneurs have had little effect on awareness and behavior change outside Europe and America, the so-called global north. The parts of the world just now creeping out of poverty have other priorities; per-capita usage and device efficiency will likely be driven more by economics than by morality. China, for example, now adds roughly one gigawatt of coal-based electricity generation every week. It has made it clear that no climate-related restrictions will impede its growth. And China exports about 99% of the solar panels they produce. If we cut US CO2 output to zero, it would amount to only a minor delay in the timing of any impending global warming catastrophe.

The global south is where the action is; but the successes of our environmental moral-entrepreneurs have not escaped the boundaries of the global north. Fortunately – and due solely to market forces – the fruits of our technological entrepreneurs travel around the globe at the speed of light. The Jevons Paradox is a dressed-up claim of elasticity of demand with regard to price. The efficiencies of Jevons’ concern were dollars per watt, not CO2 per watt. US electricity prices have climbed steadily (roughly constant when adjusted for inflation) for the past several decades. So Jevons is largely irrelevant in the US and is no reason to throw in the towel on production or consumption efficiency. To the extent that Jevons applies to scenarios where consumption is affected by regulation and peer pressure, it still begs for innovation to bring about higher efficiency devices and power generation means.

As the global south move out of poverty, they will buy refrigerators, air conditioners and cars. If all goes well, they’ll buy more efficient versions of those appliances than we did as we crawled out of poverty. If we’re luckier still, they’ll use electricity that comes from something other than the conventional coal plants they’re building at breakneck pace. That might be coal or gas with sequestration, small nuclear, or maybe fusion if we get our act together. It won’t be wind and it won’t be solar – for land-area reasons alone (do the math).

My main point here is a call for more innovation of the engineering type and less of the moral/environmental entrepreneur type. US environmentalism is becoming increasingly short-sighted, fighting a battle that, even if won decisively in the global north, is a miniscule fraction of the whole war. And that style of environmentalism has no tools to take its battle to the global south. What we can take to the global south is engineering innovation. We can’t keep that within our borders even when we try.

Engineering and innovation, with reasonable policy intervention (i.e., Jevons-neutralizing tax) can solve the problem of sustainable clean-energy generation. Behavior change is tricky and it takes time and finesse. Adoption of superior technology is much faster. I’m putting my money on the engineers.

US Wind Power Limitations – Simple Math

Posted by Bill Storage in Engineering, Sustainable Energy on October 14, 2012

I am all for wind power where it makes sense. It seems to make sense in certain high mountain passes in California where the wind is both strong and consistent – class 6 or 7 wind resources where class 3 or 4 is thought practical for power generation. For the most part, the US has thus far chosen its wind farm locations wisely in terms of energy generation. Some may say not so wisely from an aesthetic or habitat perspective, but that is not my concern here. Even without considering the base-load issues of wind (see previous post), projecting wind energy’s capability to supply a major portion of US energy demand by extrapolating from such high quality wind resources is ludicrous.

America’s wind farms on average have an output of about 1.4 watts per square meter of land they occupy. The Roscoe facility in Texas does somewhat better at about 1.9 w/sqm and California’s top locations do about 2.8 w/sqm. Data from the US Department of Energy National Renewable Energy Laboratory and AWS TruePower, a group that does wind analysis for DOE (which does seem a bit prone toward telling us what we want to hear) shows most of the US to fall far below these sites in capability.

Bold claims have been made by enthusiasts like Al Gore and advocacies like the Energy Justice Network about wind’s potential to power all our energy needs. Let’s take a quick look.

American energy demand in 2010 was 28,700 terawatts. Though peak demand is much higher than average demand, for the sake of easy (conservatively erring in wind’s favor) we can distribute that total energy consumption over 24 hours for the year and get an average power demand of 3.3 million megawatts for the US. The land area of the 48 contiguous states is 8.1 million square kilometers. With a 1.4 watts per square meter (equals 1.4 megawatts per square kilometer), we’d need 2.3 million square kilometers of wind farms to supply our 2010 consumption with wind. That amounts to 29% of the land area of the contiguous 48.

The portion of the US that would be needed to supply this power, without consideration of distribution, urban and reserved land, and wind resource quality then looks like this:

The National Renewable Energy Laboratory has published a lot of the AWS TruePower work on potential wind sites in America, usually focusing on areas with a capacity factor of 0.3 or greater, broken down by wind speed. Their charts show most of the US as having some potential for wind generation, but many wind advocates are clearly unaware that the energy contained in wind is not proportional to its velocity. It may seem that the forces of nature conspire against us, but the energy content of two mile per hour wind is only 4% of the energy content of ten mph wind. Worse yet, wind turbines are designed for peak efficiency at one specific speed; thus a wind turbine designed for 10 mph (4.5 m/s) wind will get much less than 4% of its design power with a 2 mph wind (more on that here).

The below map is based on a similar one at the DOE Wind Program site. Using Photoshop’s Hue-Saturation-Brightness tool I whitened the useless wind resources from their color coded map, removing the color for wind regions below wind power class 3 at a height of 80 meters (260 ft). Here’s what’s left, from which it is very apparent that wind can play only a limited role in American energy even if we cover every square foot of land where quality wind blows – without regard for environmental, aesthetic and practical considerations.

When President Obama recently said “all of the above” about energy policy, he certainly meant all of the above where sensible. Large subsidies to wind (which have thus far gone primarily to direct expeditures, not R&D) do not meet this requirement. Unbridled wind advocacy, whether stemming from uninformed enthusiasm, dirty politics, or corporate greed, contributes to the wickedness of our energy problem by taming a small increment of it whilst creating the illusion that the solution approach is scalable. Engineering fundamentals show that the energy problem is indeed solvable, so there’s plenty of room for optimism. But let’s not set ourselves up for disappointment by ignoring the hard facts about wind.

Wind Energy (Light)

Posted by Bill Storage in Engineering, Sustainable Energy on October 7, 2012

My previous post on wind energy was long. Here’s the executive summary, followed by two corrections resulting from reader comments.

Based on current or foreseeable grid and energy storage technology, wind energy cannot supply base-load power. It therefore cannot play a major role in energy-independence or reduction of greenhouse gases. If utility-scale storage existed, wind energy might be economically viable. Even if storage and transmission capability existed, the low energy density of wind farms combined with rarity of high-quality wind resources in the US mean that wind cannot contribute significantly toward our energy goals. Without utility-scale storage, building more wind farms also requires building more conventional electricity sources, which do not meet our greenhouse gas reduction goals.

John Droz, called “anti-wind crusader” by the Sierra Club, challenged my claim that wind receives less money than other forms of electric power, noting that this hasn’t been true in recent years. Based on US Energy Information Administration data John is indeed right and I stand corrected on that point. John observes, in his presentation materials (slide 85), that the 2010 wind subsidies exceed those to all conventional sources combined. John doesn’t include all tax breaks in his calculations, but I have done so in the chart below. Even with tax breaks added, his point on subsidies is still nearly as strong. In absolute dollars, wind subsidies plus tax breaks greatly exceed those of coal, gas or nuclear, while wind’s contribution to net power is tiny. Also note that only a small fraction of wind subsidies is R&D; most goes to direct expenditures.

Architect and Design-Thinker Richard Heimann observed that my chart of levelized costs of different energy sources made wind look too good because wind without a base-load provision isn’t realistic. In other words, there is no such thing as wind energy by itself (a point also stressed by John Droz). The second chart below (click to enlarge) shows what wind would look like if base-load capacity were added using the lowest-priced gas option (ACC gas). This raises the cost of wind considerably, putting it on the same scale as solar photovoltaic.

None of this makes wind look any better of course.

Recent Comments