Archive for category Multidisciplinarians

Science vs Philosophy Again

Posted by Bill Storage in Multidisciplinarians, Philosophy of Science on June 20, 2016

Scientists, for the most part, make lousy philosophers.

Yesterday I made a brief post on the hostility to philosophy expressed by scientists and engineers. A thoughtful reply by philosopher of science Tom Hickey left me thinking more about the topic.

Scientists are known for being hostile to philosophy and for being lousy at philosophy when they practice it inadvertently. Scientists tend to do a lousy job even at analytic philosophy, the realm most applicable to science (what counts as good thinking, evidence and proof), not merely lousy when they rhapsodize on ethics.

But science vs. philosophy is a late 20th century phenomenon. Bohr, Einstein, and Ramsey were philosophy-friendly. This doesn’t mean they did philosophy well. Many scientists, before the rift between science (“natural philosophy” as it was known) and philosophy, were deeply interested in logic, ethics and metaphysics. The most influential scientists have poor track records in philosophy – Pythagoras (if he existed), Kepler, Leibnitz and Newton, for example. Einstein’s naïve social economic philosophy might be excused for being far from his core competency, but the charge of ultracrepidarianism might still apply. More importantly, Einstein’s dogged refusal to budge on causality (“I find the idea quite intolerable that an electron exposed to radiation should chose of its own free will…”) showed methodological – if not epistemic – flaws. Still, Einstein took interest in conventionalism, positivism and the nuances of theory choice. He believed that his interest in philosophy enabled his scientific creativity:

“I fully agree with you about the significance and educational value of methodology as well as history and philosophy of science. So many people today – and even professional scientists – seem to me like somebody who has seen thousands of trees but has never seen a forest. A knowledge of the historic and philosophical background gives that kind of independence from prejudices of his generation from which most scientists are suffering. This independence created by philosophical insight is – in my opinion – the mark of distinction between a mere artisan or specialist and a real seeker after truth.” – (Einstein letter to Robert Thornton, Dec. 1944)

So why the current hostility? Hawking pronounced philosophy dead in his recent book. He then goes on to perform a good deal of thought around string theory, apparently unaware that he is reenacting philosophical work done long ago. Some of Hawking’s philosophy, at least, is well thought.

Not all philosophy done by scientists fares so well. Richard Dawkins makes analytic philosophers cringe; and his excursions into the intersection of science and religion are dripping with self-refutation.

The philosophy of David Deutsch is more perplexing. I recommend his The Beginning of Infinity for its breadth of ideas, some novel outlooks, for some captivating views on ethics and esthetics, and – out of the blue – for giving Jared Diamond the thrashing I think he deserves. That said, Deutsch’s dogmatism is infuriating. He invents a straw man he names inductivism. He observes that “since inductivism is false, empiricism is as well.” Deutsch misses the point that empiricism (which he calls a misconception) is something scientists lean slightly more or slightly less toward. He thinks there are card-carrying empiricists who need to be outed. Odd as the notion of scientists subscribing to a named philosophical position might appear, Deutsch does seem to be a true Popperian. He ignores the problem of choosing between alternative non-falsified theories and the matter of theory-ladenness of negative observations. Despite this, and despite Kuhn’s arguments, Popper remains on a pedestal for Deutsch. (Don’t get me wrong; there is much good in Popper.) He goes on to dismiss relativism, justificationism and instrumentalism (“a project for preventing progress in understanding the entities beyond our direct experience”) as “misconceptions.” Boom. Case closed. Read the book anyway.

So much for philosophy-hostile scientists and philosophy-friendly scientists who do bad philosophy. What about friendly scientists who do philosophy proud. For this I’ll nominate Sean Carroll. In addition to treating the common ground between physics and philosophy with great finesse in The Big Picture, Carroll, in interviews and on his blog (and here), tries to set things right. He says that “shut up and calculate” isn’t good enough, characterizing lazy critiques of philosophy as either totally dopey, frustratingly annoying, or deeply depressing. Carroll says the universe is a strange place, and that he welcomes all the help he can get in figuring it out.

.

Rµv – (1/2)Rgµv = 8πGTµv. This is the equation that a physicist would think of if you said “Einstein’s equation”; that E = mc2 business is a minor thing – Sean Carroll, From Eternity to Here

Up until early 20th century philosophers had material contributions to make to the physical sciences – Neil deGrasse Tyson

But You Need the Data

Posted by Bill Storage in Multidisciplinarians on January 4, 2016

In my last post, But We Need the Rain, I suggested that environmentalist animism in San Francisco may fill the role once filled by religious belief, and may suffuse daily life as Christian belief did in medieval Europe. As the phrase “God be with ye” once reminded countrymen of correct thinking, so too might acknowledgment that we need the rain.

Medieval institutions – social and governmental – exerted constant pressure steering people away from wrong thinking; and the church dissuaded its flock from asking the wrong questions. Telling a lie to save a soul was OK; deceiving heathens into Christianity was just fine. I wonder if a weaker form of this sentiment remains in my fair city – in the form of failing to mention relevant facts about an issue and through the use of deceptive and selective truths. As theologian Thomas Burnet put it in the early 18th century, too much light is hurtful to weak eyes.

The San Francisco Chronicle, according to Google data, has published over 50 articles in the last two years mentioning the Shasta and Oroville reservoirs in connection with California’s four-year-old drought. Many of these pieces call attention to low levels of these reservoirs, e.g., Shasta was at 53% of normal level in January 2014.

None mention that Shasta and Oroville were, despite the drought, at 108% and 101% of normal level in April 2013, two years into the drought. Climate is mentioned in nearly all sfgate.com articles on the drought, but mismanagement of water resources by governments is mentioned in only one. Digging a bit deeper – with other sources – you’ll find bitter disputes between farmers saying water is wasted on environmental restoration and environmentalists asking why desert farmers want to grow thirsty crops like rice and cotton. I’d think Northern California citizens, asked by the governor to bathe less, might be interested in why so much of the Shasta and Oroville water left the reservoirs – whether they want to blame Sacramento, farmers, or environmentalists – and in the details of the dispute.

Is the Chronicle part of a conspiracy to get liberals in power by linking the water shortage to climate change rather than poor governance? I doubt it. There are no conservatives to displace. More likely, it seems to me, the Chronicle simply mirrors the values and beliefs held by its readers, an unusually monolithic community with a strong uniformity of views. The sense of identification with a community here somewhat resembles that of a religious group, where there’s a tendency for beliefs to be held as true by individuals because they are widely believed by the group – and to select or reject evidence based on whether it supports a preexisting belief.

“Being crafty, I caught you with guile.” – 2 Corinthians, 12:16

But We Need the Rain

Posted by Bill Storage in Multidisciplinarians on January 1, 2016

Chance outdoor meetings on recent damp days in San Francisco tend to start or finish (or both) with the statement, “but we need the rain.” No information is conveyed by these words. Their recipient already knows we need the rain. And the speaker knows the recipient knows it. Perhaps it is said aloud to be sure the nature gods hear it and continue to pour forth the blessings. Perhaps it reveals competitive piety – a race to first claim awareness of our climate-change sins. Or maybe it has just become a pleasant closing of a street encounter along the lines of “good bye.”

Of course, we don’t need the rain. San Francisco’s water supply falls 200 miles east of here and is collected in Hetch Hetchy Reservoir, eternally under attack from activists who insist their motive is environmental restoration, not anti-capitalism. We don’t pump water that falls at sea level up into our reservoirs, nor do we collect water that falls on the coast. A coastal system that dumps rain in San Francisco does not mean it’s raining in the Sierras.

So California’s High Sierras need the rain, not us. But saying “but we need the rain” does little harm. Saying it lets the gods know we are grateful; and saying it reminds each other to be thankful.

“We need the rain” may have more in common with “good bye” than is apparent to most. Etymologists tell us that “God be with ye” became “God b’wy” by the mid-1600s, and a few decades later was “good b’wy,” well on its way to our “good bye,” which retains the ending “ye” as a reminder of its genesis

In the homogenous cultures of pre-enlightenment Europe, God was a fact of the world, not a belief of religion. “God be with ye” wasn’t seen as a religious sentiment. It was an expression of hopefulness about a universe that was powered by God almighty, the first cause and prime mover, who might just be a providential God hearing our pleas that He be with ye. Am I overly cynical in seeing a connection?

Rain be with ye.

Multiple-Criteria Decision Analysis in the Engineering and Procurement of Systems

Posted by Bill Storage in Aerospace, Multidisciplinarians, Systems Engineering on March 26, 2014

The use of weighted-sum value matrices is a core component of many system-procurement and organizational decisions including risk assessments. In recent years the USAF has eliminated weighted-sum evaluations from most procurement decisions. They’ve done this on the basis that system requirements should set accurate performance levels that, once met, reduce procurement decisions to simple competition on price. This probably oversimplifies things. For example, the acquisition cost for an aircraft system might be easy to establish. But life cycle cost of systems that includes wear-out or limited-fatigue-life components requires forecasting and engineering judgments. In other areas of systems engineering, such as trade studies, maintenance planning, spares allocation, and especially risk analysis, multi-attribute or multi-criterion decisions are common.

Weighted-sum criterion matrices (and their relatives, e.g., weighted-product, AHP, etc.) are often criticized in engineering decision analysis for some valid reasons. These include non-independence of criteria, difficulties in normalizing and converting measurements and expert opinions into scores, and logical/philosophical concerns about decomposing subjective decisions into constituents.

Years ago, a team of systems engineers and I, while working through the issues of using weighted-sum matrices to select subcontractors for aircraft systems, experimented with comparing the problems we encountered in vendor selection to the unrelated multi-attribute decision process of mate selection. We met the same issues in attempting to create criteria, weight those criteria, and establish criteria scores in both decision processes, despite the fact that one process seems highly technical, the other one completely non-technical. This exercise emphasized the degree to which aircraft system vendor selection involves subjective decisions. It also revealed that despite the weaknesses of using weighted sums to make decisions, the process of identifying, weighting, and scoring the criteria for a decision greatly enhanced the engineers’ ability to give an expert opinion. But this final expert opinion was often at odds with that derived from weighted-sum scoring, even after attempts to adjust the weightings of the criteria.

Weighted-sum and related numerical approaches to decision-making interest me because I encounter them in my work with clients. They are central to most risk-analysis methodologies, and, therefore, central to risk management. The topic is inherently multidisciplinary, since it entails engineering, psychology, economics, and, in cases where weighted sums derive from multiple participants, social psychology.

This post is an introduction-after-the-fact, to my previous post, How to Pick a Spouse. I’m writing this brief prequel to address the fact that blog excerpting tools tend to use only the first few lines of a post, and on that basis, my post appeared to be on mate selection rather than decision analysis, it’s main point.

If you’re interested in multi-attribute decision-making in the engineering of systems, please continue now to How to Pick a Spouse.

.

.

————-

Katz’s Law: Humans will act rationally when all other possibilities have been exhausted.

On Imperatives for Innovation

Posted by Bill Storage in Innovation management, Multidisciplinarians on December 9, 2013

Last year, innovation guru Julian Loren introduced me to Kim Chandler McDonald, who was researching innovators and how they think. Julian co-founded the Innovation Management Institute,and has helped many Fortune 500 firms with key innovation initiatives. I’ve had the privilege of working with Julian on large game conferences (gameferences) that prove just how quickly collaborators can dissolve communication barriers and bridge disciplines. Out of this flows proof that design synthesis, when properly facilitated, can emerge in days, not years. Kim is founder/editor of the “Capital I” Innovation Interview Series. She has built a far-reaching network of global thought leaders that she studies, documents, encourages and co-innovates with. I was honored to be interviewed for her 2013 book, !nnovation – how innovators think, act, and change our world. Find it on Amazon, or the online enhanced edition at innovationinterviews.com (also flatworld.me) to see what makes innovators like Kim, Julian and a host of others tick. In light of my recent posts on great innovators in history, reinvigorated by Bruce Vojac’s vibrant series on the same topic, Kim has approved my posting an excerpt of her conversations with me here.

How do you define Innovation?

Well that term is a bit overloaded these days. I think traditionally Innovation meant the creation of better or more effective products, services, processes, & ideas. While that’s something bigger than just normal product refinement, I think it pertained more to improvement of an item in a category rather than invention of a new category. More recently, the term seems to indicate new categories and radical breakthroughs and inventions. It’s probably not very productive to get too hung up on differentiating innovation and invention.

Also, many people, perhaps following Clayton Christensen, have come to equate innovation with market disruption, where the radical change results in a product being suddenly available to a new segment because some innovator broke a price or user-skill barrier. Then suddenly, you’re meeting previously unmet customer needs, generating a flurry of consumption and press, which hopefully stimulates more innovation. That seems a perfectly good definition too.

Neither of those definitions seem to capture the essence of the iPhone, the famous example of successful innovation, despite really being “merely” a collection of optimizations of prior art. So maybe we should expand the definitions to include things that improve quality of life very broadly or address some compelling need that we didn’t yet know we had – things that just have a gigantic “wow” factor.

I think there’s also room for seeing innovation as a new way of thinking about something. That doesn’t get much press; but I think it’s a fascinating subject that interacts with the other definitions, particularly in the sense that there are sometimes rather unseen innovations behind the big visible ones. Some innovations are innovations by virtue of spurring a stream of secondary ones. This cascade can occur across product spaces and even across disciplines. We can look at Galileo, Kepler, Copernicus and Einstein as innovators. These weren’t the plodding, analytical types. All went far out on a limb, defying conventional wisdom, often with wonderful fusions of logic, empiricism and wild creativity.

Finally, I think we have to include innovations in government, ethics and art. They occasionally do come along, and are important. Mankind went a long time without democracy, women’s rights or vanishing point perspective. Then some geniuses came along and broke with tradition – in a rational yet revolutionary way that only seemed self-evident after the fact. They fractured the existing model and shifted the paradigm. They innovated.

How important do you envisage innovation going forward?

Almost all businesses identify innovation as a priority, but despite the attention given to the topic, I think we’re still struggling to understand and manage it. I feel like the information age – communications speed and information volume – has profoundly changed competition in ways that we haven’t fully understood. I suppose every era is just like its predecessor in the sense that it perceives itself to be completely unlike its predecessors. That said, I think there’s ample evidence that a novel product with high demand, patented or not, gets you a much shorter time to milk the cow than it used to. Business, and hopefully our education system, is going to need to face the need for innovation (whether we continue with that term or not) much more directly and centrally, not as an add-on, strategy du jour, or department down the hall.

What do you think is imperative for Innovation to have the best chance of success; and what have you found to be the greatest barrier to its success?

A lot has been written about nurturing innovation and some of it is pretty good. Rather than putting design or designers on a pedestal, create an environment of design throughout. Find ways to reward design, and reward well.

One aspect of providing for innovation seems underrepresented in print – planning for the future by our education system and larger corporations. Innovating in all but the narrowest of product spaces – or idea spaces for that matter – requires multiple skills and people who can integrate and synthesize. We need multidisciplinarians, interdisciplinary teams and top-level designers, coordinators and facilitators. Despite all out talk and interest in synthesis as opposed to analysis – and our interest in holism and out-of-the-box thinking – we’re still praising ultra-specialists and educating too many of them. Some circles use the term tyranny of expertise. It’s probably applicable here.

I’ve done a fair amount of work in the world of complex systems – aerospace, nuclear, and pharmaceutical manufacture. In aerospace you cannot design an aircraft by getting a hundred specialists, one expert each in propulsion, hydraulics, flight controls, software, reliability, etc., and putting them in a room for a year. You get an airplane design by combining those people plus some who are generalists that know enough about each of those subsystems and disciplines to integrate them. These generalists aren’t jacks of all trades and masters of none, nor are they mere polymaths; they’re masters of integration, synthesis and facilitation – expert generalists. The need for such a role is very obvious in the case of an airplane, much less obvious in the case of a startup. But modern approaches to product and business model innovation benefit tremendously from people trained in multidisciplinarity.

I’m not sure if it’s the greatest barrier, but it seems to me that a significant barrier to almost any activity that combines critical thinking and creativity is to write a cookbook for that activity. We are still bombarded by consultancies, authors and charismatic speakers who capitalize on innovation by trivializing it. There’s a lot of money made by consultancies who reduce innovation to an n-step process or method derived from shallow studies of past success stories. You can get a lot of press by jumping on the erroneous and destructive left-brain/right-brain model. At best, it raises awareness, but the bandwagon is already full. I don’t think lack of interest in innovation is a problem; lack of enduring commitment probably is. Jargon-laden bullet-point lists have taken their toll. For example, it’s hard to even communicate meaningfully about certain tools or approaches to innovation using terms like “design thinking” or “systems thinking” because they’ve been diluted and redefined into meaninglessness.

What is your greatest strength?

Perspective.

What is your greatest weaknesses?

Brevity, on occasion.

Great Innovative Minds: A Discord on Method

Posted by Bill Storage in Innovation management, Multidisciplinarians on November 19, 2013

Great minds do not think alike. Cognitive diversity has served us well. That’s not news to those who study innovation; but I think you’ll find this to be a different take on the topic, one that gets at its roots.

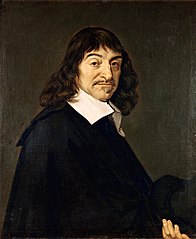

The two main figures credited with setting the scientific revolution in motion did not agree at all on what the scientific method actually was. It’s not that they differed on the finer points; they disagreed on the most basic aspect of what it meant to do science – though they didn’t yet use that term. At the time of Francis Bacon and Rene Descartes, there were no scientists. There were natural philosophers. This distinction is important for showing just how radical and progressive Descartes and Bacon were.

In Discourse on Method, Descartes argued that philosophers, over thousands of years of study, had achieved absolutely nothing. They pursued knowledge, but they had searched in vain. Descartes shared some views with Aristotle, but denied Aristotelian natural philosophy, which had been woven into Christian beliefs about nature. For Aristotle, rocks fell to earth because the natural order is for rocks to be on the earth, not above it – the Christian version of which was that it was God’s plan. In medieval Europe truths about nature were revealed by divinity or authority, not discovered. Descartes and Bacon were both devout Christians, but believed that Aristotelian philosophy of nature had to go. Observing that there is no real body of knowledge that can be claimed by philosophy, Descartes chose to base his approach to the study of nature on mathematics and reason. A mere 400 years after Descartes, we have trouble grasping just how radical this notion was. Descartes believed that the use of reason could give us knowledge of nature, and thus give us control over nature. His approach was innovative, in the broad sense of that term, which I’ll discuss below. Observation and experience, however, in Descartes’ view, could be deceptive. They had to be subdued by pure reason. His approach can be called rationalism. He sensed that we could use rationalism to develop theories – predictive models – with immense power, which would liberate mankind. He was right.

In Discourse on Method, Descartes argued that philosophers, over thousands of years of study, had achieved absolutely nothing. They pursued knowledge, but they had searched in vain. Descartes shared some views with Aristotle, but denied Aristotelian natural philosophy, which had been woven into Christian beliefs about nature. For Aristotle, rocks fell to earth because the natural order is for rocks to be on the earth, not above it – the Christian version of which was that it was God’s plan. In medieval Europe truths about nature were revealed by divinity or authority, not discovered. Descartes and Bacon were both devout Christians, but believed that Aristotelian philosophy of nature had to go. Observing that there is no real body of knowledge that can be claimed by philosophy, Descartes chose to base his approach to the study of nature on mathematics and reason. A mere 400 years after Descartes, we have trouble grasping just how radical this notion was. Descartes believed that the use of reason could give us knowledge of nature, and thus give us control over nature. His approach was innovative, in the broad sense of that term, which I’ll discuss below. Observation and experience, however, in Descartes’ view, could be deceptive. They had to be subdued by pure reason. His approach can be called rationalism. He sensed that we could use rationalism to develop theories – predictive models – with immense power, which would liberate mankind. He was right.

Francis Bacon, Descartes slightly older counterpart in the scientific revolution, was a British philosopher and statesman who became attorney general in 1613 under James I. He is now credited with being the father of empiricism, the hands-on, experimental basis for modern science, engineering, and technology. Bacon believed that acquiring knowledge of nature had to be rooted in observation and sensory experience alone. Do experiments and then decide what it means. Infer conclusions from the facts. Bacon argued that we must quiet the mind and apply a humble, mechanistic approach to studying nature and developing theories. Reason biases observation, he said. In this sense, the theory-building models of Bacon and Descartes were almost completely opposite. I’ll return to Bacon after a clarification of terms needed to make a point about him.

Innovation has many meanings. Cicero said he regarded it with great suspicion. He saw innovation as the haphazard application of untested methods to important matters. For Cicero, innovators were prone to understating the risks and overstating the potential gains to the public, while the innovators themselves had a more favorable risk/reward quotient. If innovation meant dictatorship for life for Julius Caesar after 500 years of self-governance by the Roman people, Cicero’s position might be understandable.

Today, innovation usually applies specifically to big changes in commercial products and services, involving better consumer value, whether by new features, reduced prices, reduced operator skill level, or breaking into a new market. Peter Drucker, Clayton Christensen and the tech press use innovation in roughly this sense. It is closely tied to markets, and is differentiated from invention (which may not have market impact), improvement (may be merely marginal), and discovery.

That business-oriented definition of innovation is clear and useful, but it leaves me with no word for what earlier generations meant by innovation. In a broader sense, it seems fair that innovation also applies to what vanishing point perspective brought to art during the renaissance. John Locke, a follower of both Bacon and Descartes, and later Thomas Jefferson and crew, conceived of the radical idea that a nation could govern itself by the application of reason. Discovery, invention and improvement don’t seem to capture the work of Locke and Jefferson either. Innovation seems the best fit. So for discussion purposes, I’ll call this innovation in the broader sense as opposed to the narrower sense, where it’s tied directly to markets.

That business-oriented definition of innovation is clear and useful, but it leaves me with no word for what earlier generations meant by innovation. In a broader sense, it seems fair that innovation also applies to what vanishing point perspective brought to art during the renaissance. John Locke, a follower of both Bacon and Descartes, and later Thomas Jefferson and crew, conceived of the radical idea that a nation could govern itself by the application of reason. Discovery, invention and improvement don’t seem to capture the work of Locke and Jefferson either. Innovation seems the best fit. So for discussion purposes, I’ll call this innovation in the broader sense as opposed to the narrower sense, where it’s tied directly to markets.

In the broader sense, Descartes was the innovator of his century. But in the narrow sense (the business and markets sense), Francis Bacon can rightly be called the father of innovation – and it’s first vocal advocate. Bacon envisioned a future where natural philosophy (later called science) could fuel industry, prosperity and human progress. Again, it’s hard to grasp how radical this was; but in those days the dominant view was that mankind had reached its prime in ancient times, and was on a downhill trajectory. Bacon’s vision was a real departure from the reigning view that philosophy, including natural philosophy, was stuff of the mind and the library, not a call to action or a route to improving life. Historian William Hepworth Dixon wrote in 1862 that everyone who rides in a train, sends a telegram or undergoes a painless surgery owes something to Bacon. In 1620, Bacon made, in The Great Instauration, an unprecedented claim in the post-classical world:

“The explanation of which things, and of the true relation between the nature of things and the nature of the mind … may spring helps to man, and a line and race of inventions that may in some degree subdue and overcome the necessities and miseries of humanity.”

In Bacon’s view, such explanations would stem from a mechanistic approach to investigation; and it must steer clear of four dogmas, which he called idols. Idols of the tribe are the set of ambient cultural prejudices. He cites our tendency to respond more strongly to positive evidence than to negative evidence, even if they are equally present; we leap to conclusions. Idols of the cave are one’s individual preconceptions that must be overcome. Idols of the theater refer to dogmatic academic beliefs and outmoded philosophies; and idols of the marketplace are those prejudices stemming from social interactions, specifically semantic equivocation and terminological disputes.

Descartes realized that if you were to strictly follow Bacon’s method of fact collecting, you’d never get anything done. Without reasoning out some initial theoretical model, you could collect unrelated facts forever with little chance of developing a usable theory. Descartes also saw Bacon’s flaw in logic to be fatal. Bacon’s method (pure empiricism) commits the logical sin of affirming the consequent. That is, the hypothesis, if A then B, is not made true by any number of observations of B. This is because C, D or E (and infinitely more letters) might also cause B, in the absence of A. This logical fallacy had been well documented by the ancient Greeks, whom Bacon and Descartes had both studied. Descartes pressed on with rationalism, developing tools like analytic geometry and symbolic logic along the way.

Interestingly, both Bacon and Descartes were, from our perspective, rather miserable scientists. Bacon denied Copernicanism, refused to accept Kepler’s conclusion that planet orbits were elliptical, and argued against William Harvey’s conclusion that the heart pumped blood to the brain through a circulatory system. Likewise, by avoiding empiricism, Descartes reached some very wrong conclusions about space, matter, souls and biology, even arguing that non-human animals must be considered machines, not organisms. But their failings were all corrected by time and the approaches to investigation they inaugurated. The tension between their approaches didn’t go unnoticed by their successors. Isaac Newton took a lot from Bacon and a little from Descartes; his rival Gottfried Leibniz took a lot from Descartes and a little from Bacon. Both were wildly successful. Science made the best of it, striving for deductive logic where possible, but accepting the problems of Baconian empiricism. Despite reliance on affirming the consequent, inductive science seems to work rather well, especially if theories remain open to revision.

Bacon’s idols seem to be as relevant to the boardroom as they were to the court of James I. Seekers of innovation, whether in the classroom or in the enterprise, might do well to consider the approaches and virtues of Bacon and Descartes, of contrasting and fusing rationalism and observation. Bacon and Descartes envisioned a brighter future through creative problem-solving. They broke the bonds of dogma and showed that a new route forward was possible. Let’s keep moving, with a diversity of perspectives, interpretations, and predictive models.

You’re So Wrong, Richard Feynman

Posted by Bill Storage in Innovation management, Multidisciplinarians on November 2, 2013

“Philosophy of science is about as useful to scientists as ornithology is to birds”

This post is more thoughts on the minds of interesting folk who can think from a variety of perspectives, inspired by Bruce Vojak’s Epistemology of Innovation articles. This is loosely related to systems thinking, design thinking, or – more from my perspective – the consequence of learning a few seemingly unrelated disciplines that end up being related in some surprising and useful way.

Richard Feynman ranks high on my hero list. When I was a teenager I heard a segment of an interview with him where he talked about being a young boy with a ball in a wagon. He noticed that when he abruptly pulled the wagon forward, the ball moved to the back of the wagon, and when he stopped the wagon, the ball moved forward. He asked his dad why it did that. His dad, who was a uniform salesman, put a slightly finer point on the matter. He explained that the ball didn’t really move backward; it moved forward, just not as fast as the wagon was moving. Feynman’s dad told young Richard that no one knows why a ball behaves like that. But we call it inertia. I found both points wonderfully illuminating. On the ball’s motion, there’s more than one way of looking at things. Mel Feynman’s explanation of the ball’s motion had gentle but beautiful precision, calling up thoughts about relativity in the simplest sense – motion relative to the wagon versus relative to the ground. And his statement, “we call it inertia,” got me thinking quite a lot about the difference between knowledge about a thing and the name of a thing. It also recalls Newton vs. the Cartesians in my recent post. The name of a thing holds no knowledge at all.

Feynman was almost everything a hero should be – nothing like the stereotypical nerd scientist. He cussed, pulled gags, picked locks, played drums, and hung out in bars. His thoughts on philosophy of science come to mind because of some of the philosophy-of-science issues I touched on in previous posts on Newton and Galileo. Unlike Newton, Feynman was famously hostile to philosophy of science. The ornithology quote above is attributed to him, though no one seems to have a source for it. If not his, it could be. He regularly attacked philosophy of science in equally harsh tones. “Philosophers are always on the outside making stupid remarks,“ he is quoted as saying in his biography by James Gleick.

Feynman was almost everything a hero should be – nothing like the stereotypical nerd scientist. He cussed, pulled gags, picked locks, played drums, and hung out in bars. His thoughts on philosophy of science come to mind because of some of the philosophy-of-science issues I touched on in previous posts on Newton and Galileo. Unlike Newton, Feynman was famously hostile to philosophy of science. The ornithology quote above is attributed to him, though no one seems to have a source for it. If not his, it could be. He regularly attacked philosophy of science in equally harsh tones. “Philosophers are always on the outside making stupid remarks,“ he is quoted as saying in his biography by James Gleick.

My initial thoughts were that I can admire Feynman’s amazing work and curious mind while thinking he was terribly misinformed and hypocritical about philosophy. I’ll offer a slightly different opinion at the end of this. Feynman actually engaged in philosophy quite often. You’d think he’d at least try do a good job of it. Instead he seems pretty reckless. I’ll give some examples.

Feynman, along with the rest of science, was assaulted by the wave of postmodernism that swept university circles in the ’60s. On its front line were Vietnam protesters who thought science was a tool of evil corporations, feminists who thought science was a male power play, and Foucault-inspired “intellectuals” who denied that science had any special epistemic status. Feynman dismissed all this as a lot of baloney. Most of it was, of course. But some postmodern criticism of science was a reaction – though a gross overreaction – to a genuine issue that Kuhn elucidated – one that had been around since Socrates debated the sophists. Here’s my best Readers Digest version.

All empirical science relies on affirming the consequent, something seen as a flaw in deductive reasoning. Science is inductive, and there is no deductive justification for induction (nor is there any inductive justification for induction – a topic way too deep for a blog post). Justification actually rests on a leap of inductive faith and consensus among peers. But it certainly seems reasonable for scientists to make claims of causation using what philosophers call inference to the best explanation. It certainly seems that way to me. However, defending that reasoning – that absolute foundation for science – is a matter of philosophy, not one of science.

This issue edges us toward a much more practical one, something Feynman dealt with often. What’s the difference between science and pseudoscience (the demarcation question)? Feynman had a lot of room for Darwin but no room at all for the likes of Freud or Marx. All claimed to be scientists. All had theories. Further, all had theories that explained observations. Freud and Marx’s theories actually had more predictive success than did those of Darwin. So how can we (or Feynman) call Darwin a scientist but Freud and Marx pseudoscientists without resorting to the epistemologically unsatisfying argument made famous by Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart: “I can’t define pornography but I know it when I see it”? Neither Feynman nor anyone else can solve the demarcation issue in any convincing way, merely by using science. Science doesn’t work for that task.

It took Karl Popper, a philosopher, to come up with the counterintuitive notion that neither predictive success nor confirming observations can qualify something as science. In Popper’s view, falsifiability is the sole criterion for demarcation. For reasons that take a good philosopher to lay out, Popper can be shown to give this criterion a bit too much weight, but it has real merit. When Einstein predicted that the light from distant stars actually bends around the sun, he made a bold and solidly falsifiable claim. He staked his whole relativity claim on it. If, in an experiment during the next solar eclipse, light from stars behind the sun didn’t curve around it, he’d admit defeat. Current knowledge of physics could not support Einstein’s prediction. But they did they experiment (the Eddington expedition) and Einstein was right. In Popper’s view, this didn’t prove that Einstein’s gravitation theory was true, but it failed to prove it wrong. And because the theory was so bold and counterintuitive, it got special status. We’ll assume it true until it is proved wrong.

Marx and Freud failed this test. While they made a lot of correct predictions, they also made a lot of wrong ones. Predictions are cheap. That is, Marx and Freud could explain too many results (e.g., aggressive personality, shy personality or comedian) with the same cause (e.g., abusive mother). Worse, they were quick to tweak their theories in the face of counterevidence, resulting in their theories being immune to possible falsification. Thus Popper demoted them to pseudoscience. Feynman cites the falsification criterion often. He never names Popper.

The demarcation question has great practical importance. Should creationism be taught in public schools? Should Karmic reading be covered by your medical insurance? Should the American Parapsychological Association be admitted to the American Association for the Advancement of Science (it was in 1969)? Should cold fusion research be funded? Feynman cared deeply about such things. Science can’t decide these issues. That takes philosophy of science, something Feynman thought was useless. He was so wrong.

The demarcation question has great practical importance. Should creationism be taught in public schools? Should Karmic reading be covered by your medical insurance? Should the American Parapsychological Association be admitted to the American Association for the Advancement of Science (it was in 1969)? Should cold fusion research be funded? Feynman cared deeply about such things. Science can’t decide these issues. That takes philosophy of science, something Feynman thought was useless. He was so wrong.

Finally, perhaps most importantly, there’s the matter of what activity Feynman was actually engaged in. Is quantum electrodynamics a science or is it philosophy? Why should we believe in gluons and quarks more than angels? Many of the particles and concepts of Feynman’s science are neither observable nor falsifiable. Feynman opines that there will never be any practical use for knowledge of quarks, so he can’t appeal to utility as a basis for the scientific status of quarks. So shouldn’t quantum electrodynamics (at least with level of observability it had when Feynman gave this opinion) be classified as metaphysics, i.e., philosophy, rather than science? By Feynman’s demarcation criteria, his work should be called philosophy. I think his work actually is science, but the basis for that subtle distinction is in philosophy of science, not science itself.

While degrading philosophy, Feynman practices quite a bit of it, perhaps unconsciously, often badly. Not Dawkins-bad, but still pretty bad. His 1966 speech to the National Science Teacher’s Association entitled “What Is Science?” is a case in point. He hints at the issue of whether science is explanatory or merely descriptive, but wanders rather aimlessly. I was ready to offer that he was a great scientist and a bad accidental philosopher when I stumbled on a talk where Feynman shows a different side, his 1956 address to the Engineering and Science college at the California Institute of Technology, entitled, “The Relation of Science and Religion.”

He opens with an appeal to the multidisciplinarian:

“In this age of specialization men who thoroughly know one field are often incompetent to discuss another. The great problems of the relations between one and another aspect of human activity have for this reason been discussed less and less in public. When we look at the past great debates on these subjects we feel jealous of those times, for we should have liked the excitement of such argument.”

Feynman explores the topic through epistemology, metaphysics, and ethics. He talks about degrees of belief and claims of certainty, and the difference between Christian ethics and Christian dogma. He handles all this delicately and compassionately, with charity and grace. He might have delivered this address with more force and efficiency, had he cited Nietzsche, Hume, and Tillich, whom he seems to unknowingly parallel at times. But this talk was a whole different Feynman. It seems that when formally called on to do philosophy, Feynman could indeed do a respectable job of it.

I think Richard Feynman, great man that he was, could have benefited from Philosophy of Science 101; and I think all scientists and engineers could. In my engineering schooling, I took five courses in calculus, one in linear algebra, one non-Euclidean geometry, and two in differential equations. Substituting a philosophy class for one of those Dif EQ courses would make better engineers. A philosophy class of the quantum electrodynamics variety might suffice.

————

“It is a great adventure to contemplate the universe beyond man, to think of what it means without man – as it was for the great part of its long history, and as it is in the great majority of places. When this objective view is finally attained, and the mystery and majesty of matter are appreciated, to then turn the objective eye back on man viewed as matter, to see life as part of the universal mystery of greatest depth, is to sense an experience which is rarely described. It usually ends in laughter, delight in the futility of trying to understand.” – Richard Feynman, The Relation of Science and Religion

. .

Richard Rorty: A Matter for the Engineers

Posted by Bill Storage in Multidisciplinarians, Philosophy of Science on September 13, 2012

William Storage 13 Sep 2012

Visiting Scholar, UC Berkeley Science, Technology & Society Center

Richard Rorty (1931-2007) was arguably the most controversial philosopher in recent history. Unarguably, he was the most entertaining. Profoundly influenced by Thomas Kuhn, Rorty is fascinating and inspirational, even for engineers and scientists.

Richard Rorty (1931-2007) was arguably the most controversial philosopher in recent history. Unarguably, he was the most entertaining. Profoundly influenced by Thomas Kuhn, Rorty is fascinating and inspirational, even for engineers and scientists.

Rorty’s thought defied classification – literally; encyclopedias struggle to pin philosophical categories to him. He felt that confining yourself to a single category leads to personal stagnation on all levels. An interview excerpt at the end of this post ends with a casual yet weighty statement of his confidence in engineers’ ability to save the world.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Rorty looked at familiar things in different light – and could explain his position in plain English. I never found much of Heidegger to be coherent, let alone important. No such problem with Dick Rorty.

Rorty could simplify arcane philosophical concepts. He saw similarities where others saw differences, being mostly rejected by schools of thought he drew from. This was especially true for pragmatism. Often accused of hijacking this term, Rorty offered that pragmatism is a vague, ambiguous, and overworked word, but nonetheless, “it names the chief glory of our country’s intellectual tradition.” He was enamored with moral and scientific progress, and often glowed with optimism and hope while his contemporaries brooded in murky, nihilistic dungeons.

Richard Rorty photo by Mary Rorty. Used by permission.

Richard Rorty photo by Mary Rorty. Used by permission.

Rorty called himself a “Kuhnian” apart from those Kuhnians for whom The Structure of Scientific Revolution justified moral relativism and epistemic nihilism. Rorty’s critics in the hard sciences – at least those who embrace Kuhn – have gone to great lengths to distance Kuhn from Rorty. Philosophers have done the same, perhaps a bit sore from Rorty’s denigration of analytic philosophy and his insistence that philosophers have no special claim to wisdom. Kyle Cavagnini in the Spring 2012 issue of Stance (“Descriptions of Scientific Revolutions: Rorty’s Failure at Redescribing Scientific Progress”) finds that Rorty tries too hard to make Kuhn a relativist:

“Kuhn’s work provided a new framework in philosophy of science that garnered much attention, leading some of his theories to be adopted outside of the natural sciences. Unfortunately, some of these adoptions have not been faithful to Kuhn’s original theories, and at times just plain erroneous conclusions are drawn that use Kuhn as their justification. These misreadings not only detract from the power of Kuhn’s argument, but also serve to add false support for theories that Kuhn was very much against; Rorty was one such individual.”

Cavagnini may have some valid technical points. But it’s as easy to misread Rorty as to misread Kuhn. As I read Rorty, he derives from Kuhn that the authority of science has no basis beyond scientific consensus. It then follows for Rorty that instituational science and scientists have no basis for a privileged status in acquiring truth. Scientist who know their stuff shouldn’t disagree on this point. Rorty’s position is not cultural constructivism applied to science. He doesn’t remotely imply that one claim of truth – scientific or otherwise – is as good as another. In fact, Rorty explicitly argues against that position as applied to both science and ethics. Rorty then takes ideas he got from Kuhn to places that Kuhn would not have gone, without projecting his philosophical ideas onto Kuhn:

“To say that the study of the history of science, like the study of the rest of history, must be hermeneutical, and to deny (as I, but not Kuhn, would) that there is something extra called ‘rational reconstruction’ which can legitimize current scientific practice, is still not to say that the atoms, wave packages, etc., discovered by the physical scientists are creations of the human spirit.” – Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature

“I hope to convince the reader that the dialectic within analytical philosophy, which has carried … philosophy of science from Carnap to Kuhn, needs to be carried a few steps further.” – Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature

What Rorty calls “leveling down science” is aimed at the scientism of logical positivists in philosophy – those who try to “science-up” analytic philosophy:

“I tend to view natural science as in the business of controlling and predicting things, and as largely useless for philosophical purposes” – Rorty and Pragmatism: The Philosopher Responds to his Critics

For Rorty, both modern science and modern western ethics can claim superiority over their precursors and competitors. In other words, we are perfectly capable of judging that we’ve made moral and scientific progress without a need for a privileged position of any discipline, and without any basis beyond consensus. This line of thought enabled the political right to accuse Rorty of moral relativism and at the same time the left to accuse him of bigotry and ethnocentrism. Both did vigorously. [note]

You can get a taste of Rorty from the sound and video snippets available on the web, e.g. this clip where he dresses down the standard philosophical theory of truth with an argument that would thrill mathematician Kurt Gödel:

In his 2006 Dewey Lecture in Law and Philosophy at the University of Chicago, he explains his position, neither moral absolutist nor moral relativist (though accused of being both by different factions), in praise of western progress in science and ethics.

Another example of Rorty’s nuanced position is captured on tape in Stanford’s archives of the Entitled Opinions radio program. Host Robert Harrison is an eloquent scholar and announcer, but in a 2005 Entitled Opinions interview, Rorty frustrates Harrison to the point of being tongue-tied. At some point in the discussion Rorty offers that the rest of the world should become more like America. This strikes Harrison as perverse. Harrison asks for clarification, getting a response he finds even more perverse:

Harrison: What do you mean that the rest of the world should become a lot more like America? Would it be desirable to have all the various cultures across the globe Americanize? Would that not entail some sort of loss at least at the level of diversity or certain wisdoms that go back through their own particular traditions. What would be lost in the Americanization or Norwegianization of the world?

Rorty: A great deal would be lost. A great deal was lost when the Roman Empire suppressed a lot of native cultures. A great deal was lost when the Han Empire in China suppressed a lot of native cultures […]. Whenever there’s a rise in a great power a lot of great cultures get suppressed. That’s the price we pay for history.

Asked if this is not too high a price to pay, Rorty answers that if you could get American-style democracy around the globe, it would be a small price to have paid. Harrison is astounded, if not offended:

Harrison: Well here I’m going to speak in my own proper voice and to really disagree in this sense: that I think governments and forms of government are the result of a whole host of contingent geographical historical factors whereby western bourgeois liberalism or democracy arose through a whole set of circumstances that played themselves out over time, and I think that [there is in] America a certain set of presumptions that our form of democracy is infinitely exportable … [and] that we can just take this model of American democracy and make it work elsewhere. I think experience has shown us that it’s not that easy.

Rorty: We can’t make it work elsewhere but people coming to our country and finding out how things are done in the democratic west can go back and try to imitate that in their own countries. They’ve often done so with considerable success. I was very impressed on a visit to Guangzhou to see a replica of the statue of Liberty in one of the city parks. It was built by the first generation of Chinese students to visit America when they got back. They built a replica of the Statue of Liberty in order to help to try to explain to the other Chinese what was so great about the country they’d come back from. And remember that a replica of the Statue of Liberty was carried by the students in Tiananmen Square.

Harrison (agitated): Well OK but that’s one way. What if you… Why can’t we go to China and see a beautiful statue of the Buddha or something, and understand equally – have a moment of enlightenment and bring that statue back and say that we have something to learn from this other culture out there. And why is the statue of liberty the final transcend[ant] – you say yourself as a philosopher that you don’t – that there are no absolutes and that part of the misunderstanding in the history of philosophy is that there are no absolutes. It sounds like that for you the Statue of Liberty is an absolute.

Rorty: How about it’s the best thing anybody has come up with so far. It’s done more for humanity than the Buddha ever did. And it gives us something that … [interrupted]

Harrison: How can we know that!?

Rorty: From history.

Harrison: Well, for example, what do we know about the happiness of the Buddhist cultures from the inside? Can we really know from the outside that we’re happier than they are?

Rorty: I suspect so. We’ve all had experiences in moving around from culture to culture. They’re not closed off entities, opaque to outsiders. You can talk to people raised in lots of different places about how happy they are and what they’d like.

Then it spirals down a bit further. Harrison asks Rorty if he thinks capitalism is a neutral phenomenon. Rorty replies that capitalism is the worst system imaginable except for all the others that have been tried so far. He offers that communism, nationalization of production and state capitalism were utter disasters, adding that private property and private business are the only option left until some genius comes up with a new model.

Harrison then reveals his deep concern over the environment and the free market’s effect on it, suggesting that since the human story is now shown to be embedded in the world of nature, that philosophy might entertain the topic of “life” – specifically, progressing beyond 20th century humanist utopian values in light of climate change and resource usage. Rorty offers that unless we develop fusion energy or similar, we’ve had it just as much as if the terrorists get their hands on nuclear bombs. Rorty says human life and nature are valid concerns, but that he doesn’t see that they give any reason for philosophers to start talking about life, a topic he says philosophy has thus far failed to illuminate.

This irritates Harrison greatly. At one point he curtly addresses Rorty as “my dear Dick.” Rorty’s clarification, his apparent detachment, and his brevity seem to make things worse:

Rorty: “Well suppose that we find out that it’s all going to be wiped out by an asteroid. Would you want philosophers to suddenly start thinking about asteroids? We may well collapse due to the exhaustion of natural resources but what good is it going to do for philosophers to start thinking about natural resources?”

Harrison: “Yeah but Dick there’s a difference between thinking of asteroids, which is something that is outside of human control and which is not submitted to human decision and doesn’t enter into the political sphere, and talking about something which is completely under the governance of human action. I don’t say it’s under the governance of human will, but it is human action which is bringing about the asteroid, if you like. And therefore it’s not a question of waiting around for some kind of natural disaster to happen, because we are the disaster – or one could say that we are the disaster – and that the maximization of wealth for the maximum amount of people is exactly what is putting us on this track toward a disaster.

Rorty: Well, we’ve accommodated environmental change before. Maybe we can accommodate it again; maybe we can’t. But surely this is a matter for the engineers rather than the philosophers.

A matter for the engineers indeed.

.

————————————————-

.

Notes

1) Rorty and politics: The academic left cheered as Rorty shelled Ollie North’s run for the US Senate. As usual, not mincing words, Rorty called North a liar, a claim later repeated by Nancy Reagan. There was little cheering from the right when Rorty later had the academic left in his crosshairs; perhaps they failed to notice.. In 1997 Rorty wrote that the academic left must shed its anti-Americanism and its quest for even more abusive names for “The System.” “Outside the academy, Americans still want to feel patriotic,” observed Rorty. “They still want to feel part of a nation which can take control of its destiny and make itself a better place.”

On racism, Rorty observed that the left once promoted equality by saying we were all Americans, regardless of color. By contrast, he said, the contemporary left now “urges that America should not be a melting-pot, because we need to respect one another in our differences.” He chastised the academic left for destroying any hope for a sense of commonality by highlighting differences and preserving otherness. “National pride is to countries what self-respect is to individuals,” wrote Rorty.

For Dinesh D’Souza, patriotism is no substitute for religion. D’Souza still today seems obsessed with Rorty’s having once stated his intent “to arrange things so that students who enter as bigoted, homophobic religious fundamentalists will leave college with views more like our own.” This assault on Christianity lands Rorty on a D’Souza enemy list that includes Sam Harris, Christopher Hitchens, and Richard Dawkins, D’Souza apparently unaware that Rorty’s final understanding of pragmatism included an accomodation of liberal Christianity.

2) See Richard Rorty bibliographical material and photos maintained by the Rorty family on the Stanford web site.

Kaczynski, Gore, and Cool Headed Logicians

Posted by Bill Storage in Multidisciplinarians on August 24, 2012

Yesterday I was talking to Robert Scoble about context-aware computing and we ended up on the topic of computer analysis of text. I’ve done some work in this area over the years for ancient text author attribution, cheating detection in college and professional essay exam scenarios, and for sentiment and mood analysis. A technique common to authorship studies is statistical stylometry, which aims to quantify linguistic style. Subtle but persistent differences between text written by different authors, even when writing about the same topic or in the same genre often emerge from statistical analysis of their writings.

Yesterday I was talking to Robert Scoble about context-aware computing and we ended up on the topic of computer analysis of text. I’ve done some work in this area over the years for ancient text author attribution, cheating detection in college and professional essay exam scenarios, and for sentiment and mood analysis. A technique common to authorship studies is statistical stylometry, which aims to quantify linguistic style. Subtle but persistent differences between text written by different authors, even when writing about the same topic or in the same genre often emerge from statistical analysis of their writings.

Robert was surprised to hear that Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber, was caught because of linguistic analysis, not done by computer, but by Kaczynski’s brother and sister-in-law. Contrary to stories circulating in the world of computational linguistics and semantics, computer analysis played no part in getting a search warrant or prosecuting Kaczynski. It could have, but Kaczynski plead guilty before his case went to trial. The FBI did hire James Fitzgerald, a forensic linguist, to compare Kaczynski’s writings to the Unabomber’s manifesto, and Fitzgerald’s testimony was used in the trial.

Analysis of text has uses beyond author attribution. Google’s indexing and search engine relies heavily on discovering the topic and contents of text. Sentiment analysis tries to guess how customers like a product based on their tweets and posts about it. But algorithmic sentiment analysis is horribly unreliable in its present state, failing to distinguish positive and negative sentiments the vast majority of the time. Social media monitoring tools have a long way to go.

Analysis of text has uses beyond author attribution. Google’s indexing and search engine relies heavily on discovering the topic and contents of text. Sentiment analysis tries to guess how customers like a product based on their tweets and posts about it. But algorithmic sentiment analysis is horribly unreliable in its present state, failing to distinguish positive and negative sentiments the vast majority of the time. Social media monitoring tools have a long way to go.

The problem stems from the fact that human speech and writing are highly evolved and complex. Sarcasm is common, and relies on context to reveal that you’re saying the opposite of what you mean. Subcultures have wildly different usage for overloaded terms. Retirees rarely use “toxic” and “sick” as compliments like college students do. Even merely unwinding phrases to determine the referent of a negator is difficult for computers. Sentiment analysis and topic identification rely on nouns and verbs, which are only sometimes useful in authorship studies. Consider the following sentences:

1) The twentieth century has not been kind to the constant human striving for a sense of purpose in life.

2) The Industrial Revolution and its consequences have been a disaster for the human race.

The structure, topic, and sentiment of these sentences is similar. The first is a quote from Al Gore’s 2006 Earth in the Balance. The second is the opening statement of Kaczynski’s 1995 Unabomber manifesto, “Industrial Society and its Future.” Even using the total corpus of works by Gore and Kaczynski, it would be difficult to guess which author wrote each sentence. However, compare the following paragraphs, one from each of these authors:

1) Modern industrial civilization, as presently organized, is colliding violently with our planet’s ecological system. The ferocity of its assault on the earth is breathtaking, and the horrific consequences are occurring so quickly as to defy our capacity to recognize them, comprehend their global implications, and organize an appropriate and timely response. Isolated pockets of resistance fighters who have experienced this juggernaut at first hand have begun to fight back in inspiring but, in the final analysis, woefully inadequate ways.

2) It is not necessary for the sake of nature to set up some chimerical utopia or any new kind of social order. Nature takes care of itself: It was a spontaneous creation that existed long before any human society, and for countless centuries, many different kinds of human societies coexisted with nature without doing it an excessive amount of damage. Only with the Industrial Revolution did the effect of human society on nature become really devastating.

Again, the topic, mood, and structure are similar. Who wrote which? Lexical analysis immediately identifies paragraph 1 as Gore and paragraph 2 as Kaczynski. Gore uses the word “juggernaut” twice in Earth in the Balance and once in The Assault on Reason. Kaczynski never uses the word in any published writing. Fitzgerald (“Using a forensic linguistic approach to track the Unabomber”, 2004) identified “chimerical,” along with “cool-headed logician” to be Kaczynski signatures.

Again, the topic, mood, and structure are similar. Who wrote which? Lexical analysis immediately identifies paragraph 1 as Gore and paragraph 2 as Kaczynski. Gore uses the word “juggernaut” twice in Earth in the Balance and once in The Assault on Reason. Kaczynski never uses the word in any published writing. Fitzgerald (“Using a forensic linguistic approach to track the Unabomber”, 2004) identified “chimerical,” along with “cool-headed logician” to be Kaczynski signatures.

Don’t make too much – as some of Gore’s critics do – of the similarity between those two paragraphs. Both writers have advanced degrees from prestigious universities, they share an interest in technology and environment, and are roughly the same age. Reading further in the manifesto reveals a great difference in attitudes. Though algorithms would have a hard time with the following paragraph, few human readers would identify the following excerpt with Gore (this paragraph caught my I eye because of its apparent reference to Thomas Kuhn, discussed a lot here recently – both were professors at UC Berkeley):

Modern leftist philosophers tend to dismiss reason, science, objective reality and to insist that everything is culturally relative. It is true that one can ask serious questions about the foundations of scientific knowledge and about how, if at all, the concept of objective reality can be defined. But it is obvious that modern leftist philosophers are not simply cool-headed logicians systematically analyzing the foundations of knowledge.

David Kaczynski, Ted’s brother, describes his awful realization about similarity between his brother’s language and that used in the recently published manifesto:

“When Linda and I returned from our Paris vacation, the Washington Post published the Unabomber’s manifesto. After I read the first few pages, my jaw literally dropped. One particular phrase disturbed me. It said modern philosophers were not ‘cool-headed logicians.’ Ted had once said I was not a ‘cool-headed logician’, and I had never heard anyone else use that phrase.”

And on that basis, David went to the FBI, who arrested Ted in his cabin. It’s rare that you’re lucky enough to find such highly distinctive terms in authorship studies though. In my statistical stylometry work, I looked for unique or uncommon 2- to 8-word phrases (“rare pairs“, etc.) used only by two people in a larger population, and detected unwanted collaboration by that means. Most of my analysis, and that of experts far more skilled in this field than I, is not concerned with content. Much of it centers on function-word statistics – usage of pronouns, prepositions and conjunctions. Richness of vocabulary, rate of introduction of new words, and vocabulary frequency distribution also come into play. Some recent, sophisticated techniques look at characteristics of zipped text (which obviously does include content), and use markov chains, principal component analysis and support vector machines.

And on that basis, David went to the FBI, who arrested Ted in his cabin. It’s rare that you’re lucky enough to find such highly distinctive terms in authorship studies though. In my statistical stylometry work, I looked for unique or uncommon 2- to 8-word phrases (“rare pairs“, etc.) used only by two people in a larger population, and detected unwanted collaboration by that means. Most of my analysis, and that of experts far more skilled in this field than I, is not concerned with content. Much of it centers on function-word statistics – usage of pronouns, prepositions and conjunctions. Richness of vocabulary, rate of introduction of new words, and vocabulary frequency distribution also come into play. Some recent, sophisticated techniques look at characteristics of zipped text (which obviously does include content), and use markov chains, principal component analysis and support vector machines.

Statistical stylometry has been put to impressive use with startling and unpopular results. For over a century people have been attempting to determine whether Shakespeare wrote everything attributed to him, or whether Francis Bacon helped. More recently D. I. Homes showed rather conclusively using hierarchical cluster analysis that the Book of Mormon and Book of Abraham both arose from the prophetic voice of Joseph Smith himself. Mosteller and Wallace differentiated, using function word frequency distributions, the writing of Hamilton and Madison in the Federalist Papers. They have also shown clear literary fingerprints in the writings of Jane Austen, Arthur Conan Doyle, Charles Dickens, Rudyard Kipling and Jack London. And for real fun, look into New Testament authorship studies.

Computer analysis of text is still in its infancy. I look forward to new techniques and new applications for them. Despite false starts and some exaggerated claims, this is good stuff. Given the chance, it certainly would have nailed the Unabomber. Maybe it can even determine what viewers really think of a movie.

Why Rating Systems Sometimes Work

Posted by Bill Storage in Multidisciplinarians on August 22, 2012

Goodfilms is a Melbourne based startup that aims to do a better job of recommending movies to you. Their system uses your social network, e.g., Facebook, to show you what your friends are watching, along with two attributes of films, which you rate on a 10 scale (1 to 5 stars in half-star increments). It doesn’t appear that they include a personalized recommendation system based on collaborative filtering or similar.

In today’s Goodfilms blog post, Why Ratings Systems Don’t Work, the authors point to an XKCD cartoon identifying one of the many problems with collecting ratings from users.

The Goodfilms team says the problem with averaged rating values is that they attempt to distil an entire product down to a scalar value; that is, a number along a scale from 1 to some maximum imaginable goodness. They also suggest that histograms aren’t useful, asking how seeing the distribution of ratings for a film might possibly help you judge whether you’d like it.

Goodfilms demonstrates the point using three futuristic films, Blade Runner, Starship Troopers, and Fifth Element. The Goodfilms data shows bimodal distributions for all three films; the lowest number of ratings for each film is 2, 3, or 4 stars with 1 star and 5 stars having more votes.

Goodfilms goes on to say that their system gives you better guidance. Their film-quality visualization – rather than a star bar-chart and histogram – is a two axis scatter plot of the two attributes you rate for films on their site – quality and rewatchability, how much you’d like to watch that film again.

An astute engineer or economist might note that Goodfilms assumes quality and rewatchability to be independent variables, but they clearly are not. The relationship between the two attributes is complex and may vary greatly between film watchers. Regardless of the details of how those two variables interact, they are not independent; few viewers would rate something low in quality and high in rewatchability.

An astute engineer or economist might note that Goodfilms assumes quality and rewatchability to be independent variables, but they clearly are not. The relationship between the two attributes is complex and may vary greatly between film watchers. Regardless of the details of how those two variables interact, they are not independent; few viewers would rate something low in quality and high in rewatchability.

But even if these attributes were independent of each other, films have many other attributes that might be more telling – length, realism, character development, skin exposure, originality, clarity of intent, provocation, explosion count, and an endless list of others. Even if you included 100 such variables (and had a magic visualization tool for such data), you might not capture the sentiment of a crowd of viewers about the film, let alone be able to decide whether you would like it based on that data. Now if you had some deep knowledge of how you, as an individual, compare, in aesthetics, values and mental process, to your Facebook friends and to a larger population of viewers – then we’d really know something, but that kind of analysis is still some distance out.

Goodfilms is correct in concluding that rating systems have their perils; but their solution, while perhaps a step in the right direction, is naive. The problem with rating systems is not that they don’t capture enough attributes of the rated product or in their presentation of results. The problem lies in soft things. Rating systems tend to deal more with attributes of products than with attributes of raters of those products. Recommendation systems don’t account for social influence well at all. And there’s the matter of actual preferences versus stated preference; we sometimes lie about what we like, even to ourselves.

Social influence, as I’ve noted in past posts, is profound, yet its sources can be difficult to isolate. In rating systems, knowledge of how peers or a broader population have rated what you’re about to rate strongly influence the outcome of ratings. Experiments by Salganik and others on this (discussed in this post) are truly mind boggling, showing that weak information about group sentiment not only exaggerates preferences but greatly destabilizes the system.

The Goodfilms data shows bimodal distributions for all three films. The 1 star and 5 star vote count is higher than the minimum count of the 2, 3, and 4 star rating counts. Interestingly, this is much less true for Imdb’s data. So what’s the difference? Goodfilms’ rating counts for these movies range from about 900 to 1800. Imdb has hundreds of thousands of votes for these films.

As described in a previous post (Wisdom and Madness of the Yelp Crowd), many ratings sites for various products have bimodal distributions when rating count is low, but more normally distributed votes as the count increases. It may be that the first people who rate feel the need to exaggerate their preferences to be heard. Any sentiment above middle might gets cast as 5 star, otherwise it’s 1 star. As more votes are cast, one of these extremes becomes dominant and attracts voters. Now just one vote in a crowd, those who rate later aren’t compelled to be extreme, yet are influenced by their knowledge of how others voted. This still results in exaggeration of group preferences (data is left or right skewed) through the psychological pressure to conform, but eliminates the bimodal distribution seen in the early phase of rating for a given product. There is also a tendency at Imdb for a film to be rated higher when it’s new than a year later. Bias originating in suggestion from experts surely plays a role in this too; advertising works.

As described in a previous post (Wisdom and Madness of the Yelp Crowd), many ratings sites for various products have bimodal distributions when rating count is low, but more normally distributed votes as the count increases. It may be that the first people who rate feel the need to exaggerate their preferences to be heard. Any sentiment above middle might gets cast as 5 star, otherwise it’s 1 star. As more votes are cast, one of these extremes becomes dominant and attracts voters. Now just one vote in a crowd, those who rate later aren’t compelled to be extreme, yet are influenced by their knowledge of how others voted. This still results in exaggeration of group preferences (data is left or right skewed) through the psychological pressure to conform, but eliminates the bimodal distribution seen in the early phase of rating for a given product. There is also a tendency at Imdb for a film to be rated higher when it’s new than a year later. Bias originating in suggestion from experts surely plays a role in this too; advertising works.

In the Imdb data, we see a tiny bit bimodality. The number of “1” ratings is only slightly higher that the number of “2” ratings (1-10 scale). Based on Imdb data, all three movies are all better than average – “average” being not 5.5 (halfway between 1 and 10) but either 6.2, the mean Imdb rating, or 6.4, if you prefer the median.

Imdb publishes the breakdown of ratings based on gender and age (Blade Runner, Starship Troopers, Fifth Element). Starship Troopers has considerably more variation between ratings of those under 18 and those over 30 than do the other two films. Blade Runner is liked more by older audiences than younger ones. That those two facts aren’t surprising suggests that we should be able to do better than recommending products based only on what our friends like (unless you will like something because your friends like it) or based on simple collaborative filtering algorithms (you’ll like it because others who like what you like liked it).

Imdb rating count vs. rating for 3 movies

So far, attempts to predict preferences across categories – furniture you’ll like based on your music preferences – have been rather disastrous. But movie rating systems actually do work. Yes, there are a few gray sheep, who lack preference similarity with the rest of users, but compared to many things, movies are very predictable – if you adjust for rating bias. Without knowledge that Imdb ratings are biased toward good and toward new, you high think a film with an average rating of 6 is better than average, but it isn’t, according to the Imdb community. They rate high.