Posts Tagged expansion bolt

Six Days to Failure? A Case Study in Cave Bolt Fatigue

Posted by Bill Storage in Engineering & Applied Physics on July 17, 2025

The terms fatigue failure and stress-corrosion cracking get tossed around in climbing and caving circles, often in ways that would make an engineer or metallurgist cringe. This is an investigation of a bolt failure in a cave that really was fatigue.

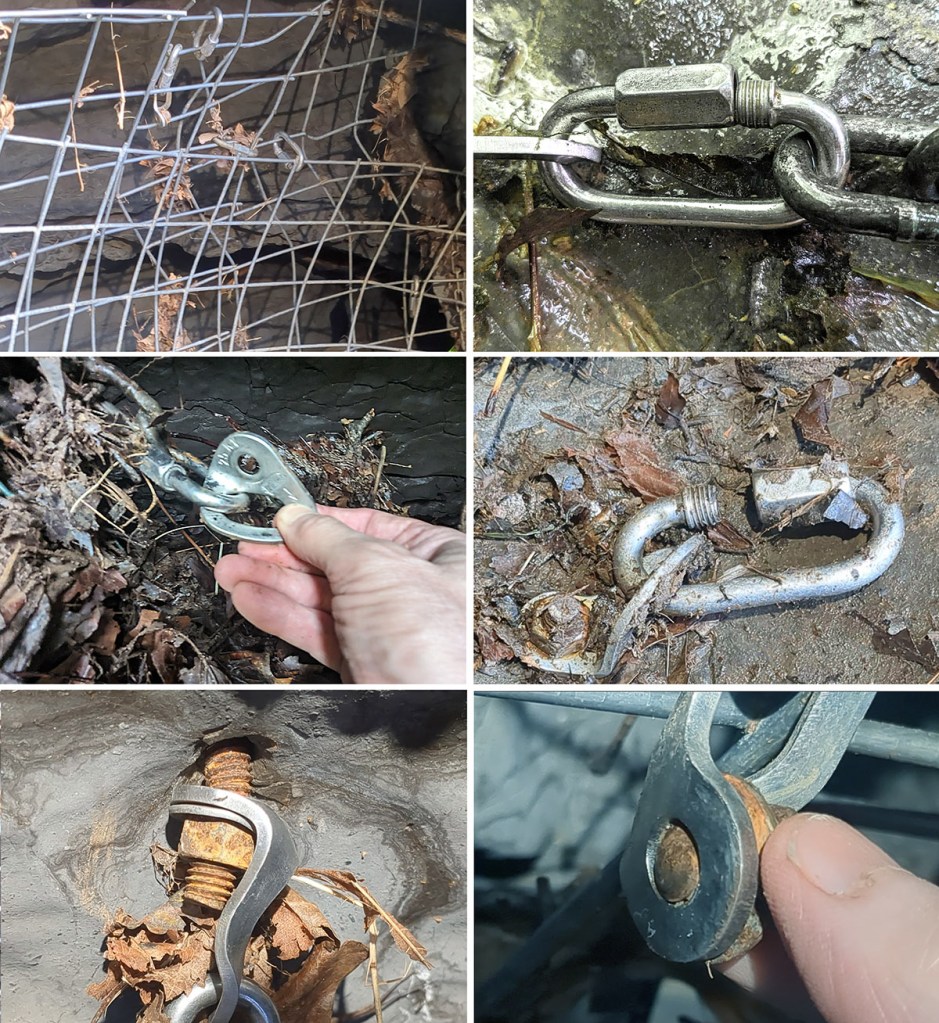

In October, we built a sort of gate to keep large stream debris from jamming the entrance to West Virginia’s Chestnut Ridge Cave. After placing 35 bolts – 3/8 by 3.5-inch, 304 stainless – we ran out. We then placed ten Confast zinc-plated mild steel wedge anchors of the same size. All nuts were torqued to between 20 and 30 foot-pounds.

The gate itself consisted of vertical chains from floor to ceiling, with several horizontal strands. Three layers of 4×4-inch goat panel were mounted upstream of the chains and secured using a mix of 304 stainless quick links and 316 stainless carabiners.

No one visited the entrance from November to July. When I returned in early July and peeled back layers of matted leaves, it was clear the gate had failed. One of the non-stainless bolts had fractured. Another had pulled out about half an inch and was bent nearly 20 degrees. Two other nuts had loosened and were missing. At least four quick links had opened enough to release chain or goat panel rods. Even pairs of carabiners with opposed gates had both opened, freeing whatever they’d been holding.

I recovered the hanger-end of the broken bolt and was surprised to see a fracture surface nearly perpendicular to the bolt’s axis, clearly not a shear break. The plane was flat and relatively smooth, with no sign of necking or the cup-and-cone profile typical of ductile tensile failure. Under magnification, the surface showed slight bumpiness, indicating the smoothness didn’t come from rubbing against the embedded remnant of the bolt. These features rule out a classic shear failure from preload loss (e.g., a nut loosening from vibration) and also rule out simple tensile overload and ductile fracture.

That leaves two possibilities: brittle tensile fracture or fatigue failure under higher-than-expected cyclic tensile load. Brittle fracture seems highly unlikely. Two potential causes exist. One is hydrogen embrittlement, but that’s rare in the low-strength carbon steel used in these bolts. The zinc-plating process likely involved acid cleaning and electroplating, which can introduce hydrogen. But this type of mild steel (probably Grade 2) is far too soft to trap it. Only if the bolt had been severely cold-worked or improperly baked post-plating would embrittlement be plausible.

The second possibility is a gross manufacturing defect or overhardening. That also seems improbable. Confast is a reputable supplier producing these bolts in massive quantities. The manufacturing process is simple, and I found no recall notices or defect reports. Hardness tests on the broken bolt (HRB ~90) confirm proper manufacturing and further suggest embrittlement wasn’t a factor.

While the available hydraulic energy at the cave entrance would seem to be low, and the 8-month time to failure is short, tensile fatigue originating at a corrosion pit emerges as the only remaining option. Its viability is supported by the partially pulled-out and bent bolt, which was placed about a foot away.

The broken bolt remained flush with the hanger, and the fracture lies roughly one hanger thickness from the nut. While the nut hadn’t backed off significantly, it had loosened enough to lose all preload. This left the bolt vulnerable to cyclic tensile loading from the attached chain vibrating in flowing water and from impacts by logs or boulders.

A fatigue crack could have initiated at a corrosion pit. Classic stress-corrosion cracking is rare in low-strength steel, but zinc-plated bolts under tension in corrosive environments sometimes behave unpredictably. The stream entering the cave has a summer pH of 4.6 to 5.0, but during winter, acidic conditions likely intensified, driven by leaf litter decay and the oxidation of pyrites in upstream Mauch Chunk shales after last year’s drought. The bolt’s initial preload would have imposed tensile stresses at 60–80% of yield strength. In that environment, stress-corrosion cracking is at least plausible.

More likely, though, preload was lost early due to vibration, and corrosion initiated a pit where the zinc plating had failed. The crack appears to have originated at the thread root (bottom right in above photo) and propagated across about two-thirds of the cross-section before sudden fracture occurred at the remaining ligament (top left).

The tensile stress area for 3/8 x 16 bolt would be 0.0775 square inches. If 65% was removed by fatigue, the remaining area would be 0.0271 sq. in. Assuming the final overload occurred at a tensile stress of around 60 ksi (SAE J429 Grade 2 bolts), then the final rupture would have required a tensile load of about 1600 pounds, a plausible value for a single jolt from a moving log or sudden boulder impact, especially given the force multiplier effect of the gate geometry, discussed below.

In mild steel, fatigue cracks can propagate under stress ranges as low as 10 to 30 percent of ultimate tensile strength, given a high enough number of cycles. Based on published S–N curves for similar material, we can sketch a basic relationship between stress amplitude and cycles to failure in an idealized steel rod (see columns 1 and 2 below).

Real-world conditions, of course, require adjustments. Threaded regions act as stress risers. Standard references assign a stress concentration factor (Kₜ) of about 3 to 4 for threads, which effectively lowers the endurance limit by roughly 40 percent. That brings the endurance limit down to around 7.5 ksi.

Surface defects from zinc plating and additional concentration at corrosion pits likely reduce it by another 10 percent. Adjusted stress levels for each cycle range are shown in column 3.

Does this match what we saw at the cave gate? If we assume the chain and fencing vibrated at around 2 Hz during periods of strong flow – a reasonable estimate based on turbulence – we get about 172,000 cycles per day. Just six days of sustained high flow would yield over a million cycles, corresponding to a stress amplitude of roughly 7 ksi based on adjusted fatigue data.

Given the bolt’s original cross-sectional area of 0.0775 in², a 7 ksi stress would require a cyclic tensile load of about 540 pounds.

| Cycles to Failure | Stress amplitude (ksi) | Adjusted Stress |

| ~10³ | 40 ksi | 30 ksi |

| ~10⁴ | 30 ksi | 20 ksi |

| ~10⁵ | 20 ksi | 12 ksi |

| ~10⁶ | 15 ksi | 7 ksi |

| Endurance limit | 12 ksi | 5 ksi |

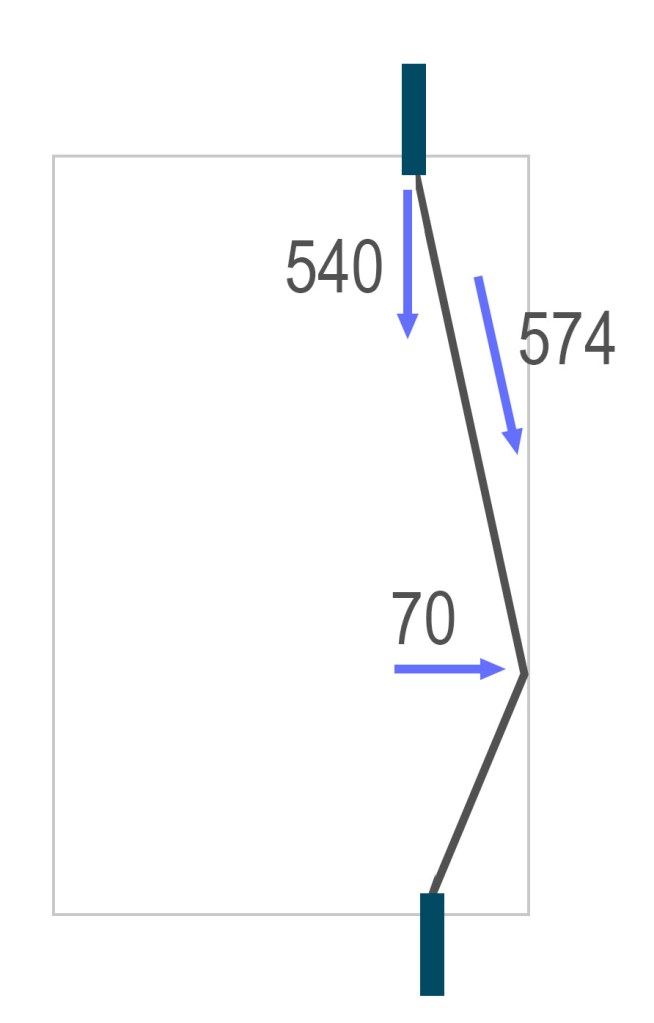

Could our gate setup impose 540-pound axial loads on ceiling bolts? Easily – and the geometry shows how. In load-bearing systems like the so-called “death triangle,” force multiplication depends on the angle between anchor points. This isn’t magic. It’s just static equilibrium: if an object is at rest, the vector sum of forces acting on it in every direction must be zero (as derived from Newton’s first two laws of mechanics).

In our case, if the chain between two vertically aligned bolts sags at a 20-degree angle, the axial force on each bolt is multiplied by about a factor of eight. That means a horizontal force of just 70 pounds – say, from a bouncing log – can produce an axial load (vertical load on the bolt) of 540 pounds.

Under the conditions described above, six days of such cycling would be enough to trigger fatigue failure at one million cycles. If a 100-pound force was applied instead, the number of cycles to failure would drop to around 100,000.

The result was genuinely surprising. I knew the principles, but I hadn’t expected fatigue at such low stress levels and with so few cycles. Yet the evidence is clear. The nearby bolt that pulled partly out likely saw axial loads of over 1,100 pounds, enough to cause failure in just tens of thousands of cycles had the broken bolt been in its place. The final fracture area on the failed bolt suggests a sudden tensile load of around 1,600 pounds. These numbers confirm that the gate was experiencing higher axial forces on bolts than we’d anticipated.

The root cause was likely a corrosion pit, inevitable in this setting, and something stainless bolts (304 or 316) would have prevented, though stainless wouldn’t have stopped pullout. Loctite might help quick links resist opening under impact and vibration, though that’s unproven in this context. Chains, while easy to rig, amplified axial loads due to their geometry and flexibility. Stainless cable might vibrate less in water. Unfortunately, surface conditions at the entrance make a rigid or welded gate impractical. Stronger bolts – ½ or even ⅝ inch – torqued to 55 to 85 foot-pounds may be the only realistic improvement, though installation will be a challenge in that setting.

More broadly, this case illustrates how quickly nature punishes the use of non-stainless anchors underground.

Recent Comments