Posts Tagged mountaineering

Climbing Taiwan Removable Bolts Review

Posted by Bill Storage in Engineering & Applied Physics on November 6, 2025

Friends and I have been experimenting with removable bolts in muddy caves, and many of us have been concerned about the robustness of the devices. I don’t mean their strength. They’re plenty strong. I mean how well do they hold up in a cave environment – and can we be ensured of a good placement. I just got some new removable bolts from Climbing Taiwan (CT). Compared to the Petzl Pulse design, which have proven to be finicky in caves, they look like they might be better suited for use in cave environments.

I don’t have a cave or a hammer drill on hand right now, so I put a 10mm masonry bit in my handheld driver and drilled holes in a concrete block to test the bolts.

For this testing I wanted to drill the hole barely long enough to fit the bolt in – against the recommendations of the manufacturer. I wanted to experiment with the consequences of crud in the bottom of the hole.

Normally, with 3/8 and 10mm bolts wedge bolts wedge bolts I don’t blow out the holes or brush them underground. I merely withdraw the drill with it rotating slightly and pull the dust out of the hole. I’ve placed hundreds of bolts and have never had a spinner. I torque my 3/8 wedge bolts to 25 foot pounds underground.

Because, for these tests, I am drilling vertically downward and I am using a masonry bit instead of a hammer drill bit, I had to brush the dust out of these holes. I did not use a blow tube. This is really bad bolting hygiene. I wanted to see if I could gum up the works. I am intentionally using these removable bolts wrong, against the advice of the manufacturer, and against good sense.

To simulate the abuse that bolts take underground, I first mixed the concrete dust with water and packed it onto the bolt mechanism. Then I poured the sludge into the hole.

Then I added sand to the mix. I packed on as much sand as I could. I also tried getting sand into the threads at the top of the hanger. This proved no problem for installation or removal. I then pushed sand into the hole to see if I could force the wedge through the sand sludge and back toward the outside of the hole.

For the next simulation of cave mud I combined honey and cornstarch. Wet corn starch is fun to use in these experiments because it is a non-euclidean fluid with some odd properties. I again added sand. I then smeared the cornstarch honey sand combination along the sleeve and the threaded region.

For the next test I got a fresh cylinder of clay- rich mud and added it to the mix. The bolt and the sludge clearly filled the entire hole as is visible by the overflow. I did the same with a mix of plumber’s grease and garden dirt. Again, no problem.

I used a pressure washer to clean them. I took them apart to be sure. Good as new.

The manufacturer says they used 2205 stainless steel for the threaded shaft and 304 for everything else. These are smart choices that reflect sound engineering. 304 is very widely used. It’s machinable and has high ductility. Its ultimate strength is several times higher than its yield strength. It is extremely forgiving and has excellent corrosion resistance. Duplex 2205 is much stronger, much more expensive, and has some trade-offs (like weldability), none of which are at all relevant to this usage.

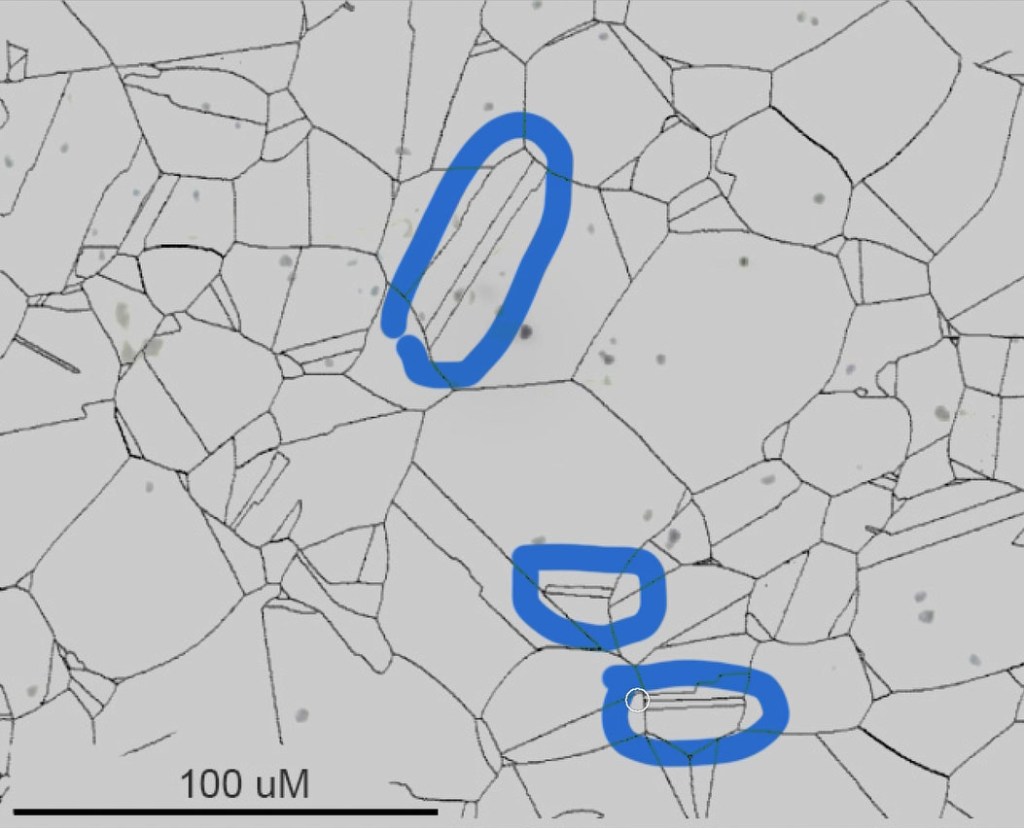

I tested the components for ferromagnetism. In theory, 304 alloy hangers should not be magnetic. OK, little bit of engineering here. 304 is austenitic; its atoms are arranged in a body-centered cubic structure. But when you cut or beat on austenitic stainless, you can cause some degree of room-temperature phase transformation. A room-temperature crystalline phase change always seemed like magic to me, but it happens. Ancient blacksmiths were similarly amazed. This cold-working causes atoms to jump into a body-centered tetragon pattern called martensite, which is magnetic. It also causes carbon atoms to bunch up a bit, and this can reduce corrosion life.

But these bolts are not intended as permanent anchors. And when I look at the hangers under a scope at 250x, I see maybe a couple of percent martensite. Rough calculation of the life of a 304 bolt in a typical Appalachian cave with no brine and low chlorides yields a range of about 1000 to 20,000 years. If we shift that bolt into its martensitic state, we’d reduce its life in a cave down to maybe 50 to 1,000 years. But that is for full martensite, and I’m seeing only a percent or two. In other words, we can ignore the fact that this hanger is slightly magnetic. The Duplex 2205 threaded shaft (“duplex” because it is part ferrite, part austenite – elongated austenite grains in a ferritic matrix, so it is magnetic), since it isn’t welded or otherwise altered, would have a corrosion life of 2 to 5 times that of 304.

I measured hardness at Rockwell C25 – around 90,000 psi – a bit higher than you’d expect for annealed 304, but consistent with the cold working that resulted in the magnetism. Totally inconsequential.

I generally don’t do destructive testing. It’s usually pointless or worse. It’s entertaining to watch gear break, but focusing on ultimate strength just encourages dangerous misconceptions. Safety in climbing gear depends on how forces are distributed, how materials deform, and, mostly, how elasticity affects the system – how energy is absorbed. The inelasticity of a static rope that’s stronger than a dynamic rope can kill you. F=ma and F=kx are not just equations – they are life-and-death considerations.

I like to look at the underlying physics, and highlight what matters in practical use. My goal is to give climbers accurate, responsible insight – not spectacle – and to counter the intuition that ‘stronger = safer.’ This approach is personal to me as well: a close friend died while aid climbing in a cave because he misunderstood these principles. We might honor his memory by helping others understand how stuff works.

Why not break them? The removable-bolt components – bolts and hangers – are made from standard engineering materials, like 304. These materials are mass-produced in sheet and rod form, and have extremely low likelihood of defects. 304 stainless is not a cottage-industry alloy. Producing it requires integrated melt, alloying, and forging infrastructure with tight control of composition and processing. You can’t fake it cheaply. So the global quality variation for 304 is extremely narrow compared to, say, low-alloy steels, bronze, or, unfortunately for cavers, aluminum castings and forgings. Counterfeit carabiners. But that’s another article.

Breaking these bolts on video would add zero real information. Their strength far exceeds what a human body can impose or withstand. What actually matters – the rock quality, technique, and proper installation – is rarely tested or demonstrated on YouTube. If there is concern about a manufacturer’s integrity, destructive testing of one or two bolts is meaningless. Instead, careful microstructural examination and non-destructive testing across a larger sample set provide meaningful insight, without teaching viewers some sort of cargo-cult science. Removable bolts are intended for shear loading only. Think standard aid climbs, not ones like this:

But any real-world usage involves some amount of axial load. Tests on other removable bolts show them to have very high strength in the axial direction. Usually, the rock blows out first.

The fact that the rock usually blows out first points to another advantage of these Climbing Taiwan bolts over the Petzl. In soft rock, bolt length trumps bolt diameter because rock strength dominates. The 3-inch, 10mm diameter CT bolt vs. the 2 and a quarter inch Petzl 12mm. In hard rock, bolt strength dominates, but in hard rock, the breaking strength for both 10 and 12mm far exceed survivability. This is a perfect example of where destructive testing results will lead you to the wrong conclusion.

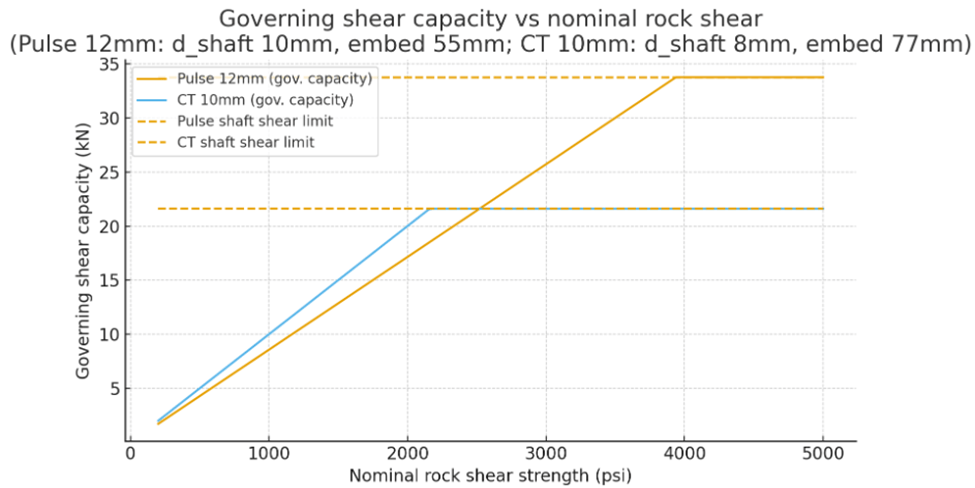

With a few assumptions, we can easily calculate the relative performance of the Pulse and the CT bolts loaded in shear:

Sleeve / shaft sizes

- Pulse: sleeve Ø = 12.0 mm, shaft Ø = 10.0 mm, embed length = 55 mm

- CT (10 mm): sleeve Ø = 10.0 mm, shaft Ø = 8.0 mm, embed length = 77 mm.

- Material strengths (conservative working numbers)

- Sleeve material 304 stainless, UTS = 520 MPa. Shear strength = 0.6·UTS = 312 MPa.

- Shaft material 2205 duplex, UTS = 860 MPa. Shear strength = 0.6·UTS = 516 MPa.

- Use the shaft shear (2205) as the bolt shear limit.

- Two limiting modes considered, and the lower one governs:

For rock-limited shear:

Rock shear strength × lateral contact area of the sleeve (projected cylindrical area = π·d_sleeve·embed_length). This models shear/punching or interface shear of the sleeve against rock.

For bolt (shaft) shear:

Material shear strength × cross-sectional area of the shaft (π·d^2/4). This models a straight shear through the shaft.

No complex friction, bending, or stress concentrations included. This is a first-order, worst-case shear capacity comparison.

| Rock shear strength | Pulse 12 mm, embed 55 mm | CT 10 mm, embed 77 mm |

| 1000 psi | rock limit 14.30 kN (3,214 lb) bolt limit 40.53 kN (9,111 lb) | rock limit 16.68 kN (3,761 lb) bolt limit 25.94 kN (5,831 lb) |

| 2000 psi | rock limit 28.59 kN (6,428 lb) bolt limit 40.53 kN (9,111 lb) | rock limit 33.36 kN (7,523 lb) bolt limit 25.94 kN (5,831 lb) |

| 4000 psi | rock limit 57.18 kN (12,855 lb) bolt limit 40.53 kN (9,111 lb) | rock limit 66.71 kN (14,998 lb) bolt limit 25.94 kN (5,831 lb) |

To evaluate the sensitivity of this model to assumptions, we can make the following changes, aiming at higher conservatism:

- 2205 duplex shear taken as 0.5·UTS, i.e. 430 MPa.

- A conservative Rock-punching reduction factor of 0.6 applied to the nominal rock shear strength to model local failure modes, stress concentrations, and imperfect contact.

| Rock shear strength | Pulse 12 mm, embed 55 mm | CT 10 mm, embed 77 mm |

| 1000 psi | rock limit 8.58 kN (1,928 lb) bolt limit 33.77 kN (7,592 lb) | rock limit 10.01 kN (2,250 lb) bolt limit 21.61 kN (4,859 lb) |

| 2000 psi | rock limit 17.16 kN (3,857 lb) bolt limit 33.77 kN (7,592 lb) | rock limit 20.01 kN (4,499 lb)bolt limit 21.61 kN (4,859 lb) |

| 4000 psi | rock limit 34.31 kN (7,713 lb) bolt limit 33.77 kN (7,592 lb) | rock limit 40.03 kN (8,999 lb) bolt limit 21.61 kN (4,859 lb) |

This results in lower strength values for both rock and bolt, but the relationships and conclusions still stand. In weak rock, length trumps diameter; in strong rock, bolt strength dominates but both 10 and 12mm strengths are far above survivability. The below chart plots governing capacity vs nominal rock shear to show the crossover points:

So my conclusion that the CT bolts are better designed for cave rock than the Petzl Pulses is not sensitive to assumptions about Rock-punching reduction factor or the relationship between 2205’s ultimate tensile and ultimate shear strength. The CT bolts come out looking like a better design for cave rock (and, of course, neither was designed for use in caves).

It’s also worth noting that the longer 10mm CT bolt removes 10 percent less rock than the shorter 12mm Petzl bolt. So you’re getting about 10% more bolting per battery.

Returning to axial strength. Because the core principle at work in these bolts is lateral expansion under confinement (a radial pressure multiplier from a low-angle taper), we need to control the hole diameter to achieve the needed confinement. These Climbing Taiwan bolts allow you to torque them down – in a sense. This isn’t torquing to achieve tensile preload, as in wedge anchors. It is about mechanically setting the wedge to the local bore diameter. Think of it like calibrating the anchor to the hole. You can expand the sleeve using the handle until you feel firm engagement. That lets you tune for real-world variability in hole diameter, rock roughness, or small flares and cracks. That seems to me the big advantage of this design; it’s more tolerant of the wobbly drilling that sub-optimal cave settings often give us.

Beyond being easier to clean and having superior strength in soft rock compared to the 12mm Petzl Pulse, the cleverness here is in better decoupling hole-fit adjustment from load resistance. I was able to engage the nominally 10mm bolt in a 12mm diameter hole. I’ll still avoid drilling bad holes, but this is very good to know, especially when drilling in confined or awkward places where suddenly the little Milwaukee decides to go on a rotary rampage.

If you have experience with these underground, or have questions or comments, please feel free to add a comment below. Sometimes I miss real engineering.

Recent Posts

- What ‘Project Hail Mary’ Gets Right about Science

- Anger As Argument – the Facebook Dividend

- Crystals Know What Day It Is

- Don’t Skimp on Shoes

- Dugga Dugga Dugga

- Robert Reich, Genius

- Bridging the Gap: Investor – Startup Psychology and What VCs Really Want to Hear

- Lawlessness Is a Choice, Bugliosi Style

- Fattening Frogs For Snakes

- Carving the Eagle

- It’s the Losers Who Write History

- Removable Climbing Bolt Stress Under Offset Loading

- Things to See in Palazzo Massimo

- Climbing Taiwan Removable Bolts Review

- The Arch of Constantine

- Deficient Discipleship in Environmental Science

- The End of Science Again

- Mark as Midrash

- Physics for Cold Cavers: NASA vs Hefty and Husky

- I’m Only Neurotic When – Engineering Edition

- I’m Only Neurotic When You Do It Wrong

- The Comet, the Clipboard, and the Knife

- Cave Bolts – 3/8″ or 8mm? – Or Wrong Question?

- Roxy Music and Forgotten Social Borders

- “He Tied His Lace” – Rum, Grenades and Bayesian Reasoning in Peaky Blinders

- Gospel of Mark: A Masterpiece Misunderstood, Part 7 – Mark Before Modernism

- Gospel of Mark, Masterpiece Misunderstood, Part 6 – Mark, Paul and James: The Silence, the Self and the Law

- The Gospel of Mark: A Masterpiece Misunderstood, Part 5 – Mark’s Interpreter Speaks

Archives

Recent Comments