Posts Tagged Strategy

Rational Atrocity?

Posted by Bill Storage in Probability and Risk on July 4, 2025

Bayesian Risk and the Internment of Japanese Americans

We can use Bayes (see previous post) to model the US government’s decision to incarcerate Japanese Americans, 80,000 of which were US citizens, to reduce a perceived security risk. We can then use a quantified risk model to evaluate the internment decision.

We define two primary hypotheses regarding the loyalty of Japanese Americans:

- H1: The population of Japanese Americans are generally loyal to the United States and collectively pose no significant security threat.

- H2: The population of Japanese Americans poses a significant security threat (e.g., potential for espionage or sabotage).

The decision to incarceration Japanese Americans reflects policymakers’ belief in H2 over H1, updated based on evidence like the Niihau Incident.

Prior Probabilities

Before the Niihau Incident, policymakers’ priors were influenced by several factors:

- Historical Context: Anti-Asian sentiment on the West Coast, including the 1907 Gentlemen’s Agreement and 1924 Immigration Act, fostered distrust of Japanese Americans.

- Pearl Harbor: The surprise attack on December 7, 1941, heightened fears of internal threats. No prior evidence of disloyalty existed.

- Lack of Data: No acts of sabotage or espionage by Japanese Americans had been documented before Niihau. Espionage detection and surveillance were limited. Several espionage rings tied to Japanese nationals were active (Itaru Tachibana, Takeo Yoshikawa).

Given this, we can estimate subjective priors:

- P(H1) = 0.99: Policymakers might have initially been 99 percent confident that Japanese Americans were loyal, as they were U.S. citizens or long-term residents with no prior evidence of disloyalty. The pre-Pearl Harbor Munson Report (“There is no Japanese `problem’ on the Coast”) supported this belief.

- P(H2) = 0.01: A minority probability of threat due to racial prejudices, fear of “fifth column” activities, and Japan’s aggression.

These priors are subjective and reflect the mix of rational assessment and bias prevalent at the time. Bayesian reasoning (Subjective Bayes) requires such subjective starting points, which are sometimes critical to the outcome.

Evidence and Likelihoods

The key evidence influencing the internment decision was the Niihau Incident (E1) modeled in my previous post. We focus on this, as it was explicitly cited in justifying internment, though other factors (e.g., other Pearl Harbor details, intelligence reports) played a role.

E1: The Niihau Incident

Yoshio and Irene Harada, Nisei residents, aided Nishikaichi in attempting to destroy his plane, burn papers, and take hostages. This was interpreted by some (e.g., Lt. C.B. Baldwin in a Navy report) as evidence that Japanese Americans might side with Japan in a crisis.

Likelihoods:

P(E1|H1) = 0.01: If Japanese Americans are generally loyal, the likelihood of two individuals aiding an enemy pilot is low. The Haradas’ actions could be seen as an outlier, driven by personal or situational factors (e.g., coercion, cultural affinity). Note that this 1% probability is not the same 1% probability of H1, the prior belief that Japanese Americans weren’t loyal. Instead, P(E1|H1) is the likelihood assigned to whether E1, the Harada event, would have occurred given than Japanese Americans were loyal to the US.

P(E1|H2) = 0.6: High likelihood of observing the Harada evidence if the population of Japanese Americans posed a threat.

Posterior Calculation Using Bayes Theorem:

P(H1∣E1) = P(E1∣H1)⋅P(H1) / [P(E1∣H1)⋅P(H1)+P(E1∣H2)⋅P(H2)]

P(H1∣E1)=0.01⋅0.99 / [(0.01⋅0.99)+(0.6⋅0.01)] = 0.626

P(H2|E1) = 1 – P(H1|E1) = 0.374

The Niihau Incident significantly increases the probability of H2 (its prior was 0.01), suggesting a high perceived threat. This aligns with the heightened alarm in military and government circles post-Niihau. 62.6% confidence in loyalty is unacceptable by any standards. We should experiment with different priors.

Uncertainty Quantification

- Aleatoric Uncertainty: The Niihau Incident involved only two people.

- Epistemic Uncertainty: Prejudices and wartime fear would amplify P(H2).

Sensitivity to P(H1)

The posterior probability of H2 is highly sensitive to changes in P(H2) – and to P(H1) because they are linearly related: P(H2) = 1.0 – P(H1).

The posterior probability of H2 is somewhat sensitive to the likelihood assigned to P(E1|H1), but in a way that may be counterintuitive – because it is the likelihood assigned to whether E1, the Harada event, would have occurred given than Japanese Americans were loyal. We now know them to have been loyal, but that knowledge can’t be used in this analysis. Increasing this value lowers the posterior probability.

The posterior probability of H2 is relatively insensitive to changes in P(E1|H2), the likelihood of observing the evidence if Japanese Americans posed a threat (which, again, we now know them to have not).

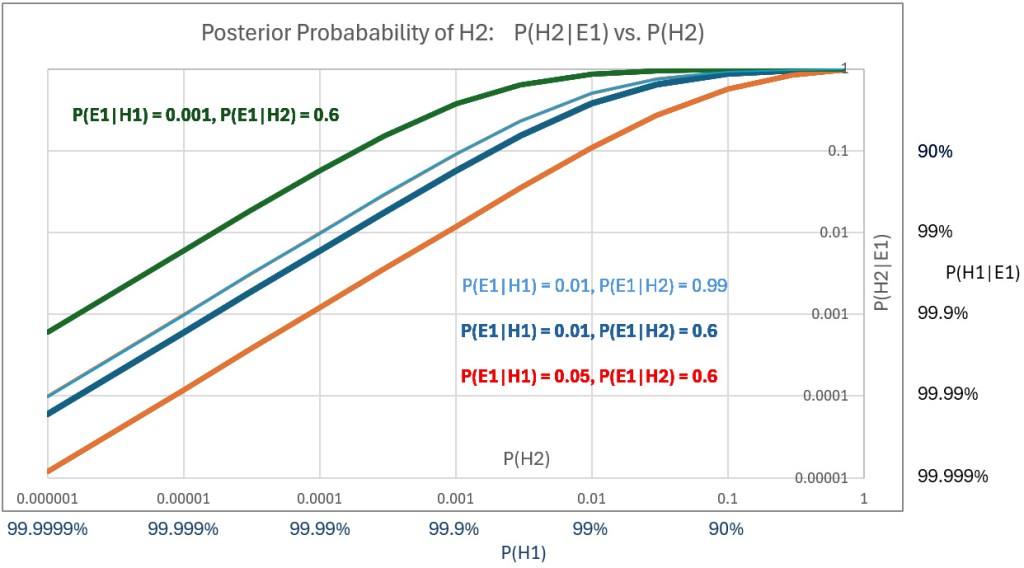

A plot of posterior probability of H2 against the prior probabilities assigned to H2 – that is, P(H2|E1) vs P(H2) – for a range of values of P(H2) using three different values of P(E1|H1) shows the sensitivities. The below plot (scales are log-log) also shows the effect of varying P(E1|H2); compare the thin blue line to the thick blue line.

Prior hypotheses with probabilities greater the 99% represent confidence levels that are rarely justified. Nevertheless, we plot high posteriors for priors of H1 (i.e., posteriors of H2 down to 0.00001 (1E-5). Using P(E1|H1) = 0.05 and P(E1|H2 = 0.6, we get a posterior P(H2|E1) = 0.0001 – or P(H1|E1) = 99.99%, which might be initially judged as not supporting incarceration of US citizens in what were effectively concentration camps.

Risk

While there is no evidence of either explicit Bayesian reasoning or risk quantification by Franklin D. Roosevelt or military analysts, we can examine their decisions using reasonable ranges of numerical values that would have been used if numerical analysis had been employed.

We can model risk, as is common in military analysis, by defining it as the product of severity and probability – probability equal to that calculated as the posterior probability that a threat existed in the population of 120,000 who were interned.

Having established a range of probabilities for threat events above, we can now estimate severity – the cost of a loss – based on lost lives and lost defense capability resulting from a threat brought to life.

The Pearl Harbor attack itself tells us what a potential hazard might look like. Eight U.S. Navy battleships were at Pearl Harbor: Arizona, Oklahoma, West Virginia, California, Nevada, Tennessee, Maryland, and Pennsylvania. Typical peacetime crew sizes ranged from 1,200 to 1,500 per battleship, though wartime complements could exceed that. About 8,000–10,000 sailors were assigned to the battleships. More sailors would have been on board had the attack not happened on a Sunday morning.

About 37,000 Navy and 14,000 Army personnel were stationed at Pearl Harbor. 2,403 were killed in the attack, most of them aboard battleships. Four battleships were sunk. The Arizona suffered a catastrophic magazine explosion from a direct bomb hit. Over 1,170 crew members were killed. 400 were killed on the Oklahoma when it sank. None of the three aircraft carriers of the Pacific Fleet were in Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7. The USS Enterprise was due to be in port on Dec. 6 but was delayed by weather. Its crew was about 2,300 men.

Had circumstances differed slightly, the attack would not have been a surprise, and casualties would have been fewer. But in other conceivable turns of events, they could have been far greater. A modern impact analysis of an attack on Pearl Harbor or other bases would consider an invasion’s “cost” to be 10 to 20,000 lives and the loss of defense capability due to destroyed ships and aircraft. Better weather could have meant destruction of one third of US aircraft carriers in the Pacific.

Using a linear risk model, an analyst, if such analysis was done back then, might have used the above calculated P(H2|E1) as the probability of loss and 10,000 lives as one cost of the espionage. Using probability P(H1) in the range of 99.99% confidence in loyalty – i.e., P(H2) = 1E-4 – and severity = 10,000 lives yields quantified risk.

As a 1941 risk analyst, you would be considering a one-in-10,000 chance of losing 10,000 lives and loss of maybe 25% of US defense capacity. Another view of the risk would be that each of 120,000 Japanese Americans poses a one-in-10,000 chance of causing 10,000 deaths, an expected cost of roughly 120,000 lives (roughly, because the math isn’t quite as direct as it looks in this example).

While I’ve modeled the decision using a linear expected value approach, it’s important to note that real-world policy, especially in safety-critical domains, is rarely risk-neutral. For instance, Federal Aviation Regulation AC 25.1309 states that “no single failure, regardless of probability, shall result in a catastrophic condition”, a clear example of a threshold risk model overriding probabilistic reasoning. In national defense or public safety, similar thinking applies. A leader might deem a one-in-10,000 chance of catastrophic loss (say, 10,000 deaths and 25% loss of Pacific Fleet capability) intolerable, even if the expected value (loss) were only one life. This is not strictly about math; it reflects public psychology and political reality. A risk-averse or ambiguity-intolerant government could rationally act under such assumptions.

Would you take that risk, or would you incarcerate? Would your answer change if you used P(H1) = 99.999 percent? Could a prior of that magnitude ever be justified?

From the perspective of quantified risk analysis (as laid out in documents like FAR AC 25.1309), President Roosevelt, acting in early 1942 would have been justified even if P(H1) had been 99.999%.

In a society so loudly committed to consequentialist reasoning, this choice ought to seem defensible. That it doesn’t may reveal more about our moral bookkeeping than about Roosevelt’s logic. Racism existed in California in 1941, but it unlikely increased scrutiny by spy watchers. The fact that prejudice existed does not bear on the decision, because the prejudice did not motivate any action that would have born – beyond the Munson Report – on the prior probabilities used. That the Japanese Americans were held far too long is irrelevant to Roosevelt’s decision.

Since the rationality of Roosevelt’s decision, as modeled by Bayesian reasoning and quantified risk, ultimately hinges on P(H1), and since H1’s primary input was the Munson Report, we might scrutinize the way the Munson Report informs H1.

The Munson Report is often summarized with its most quoted line: “There is no Japanese ‘problem’ on the Coast.” And that was indeed its primary conclusion. Munson found Japanese American citizens broadly loyal and recommended against mass incarceration. However, if we assume the report to be wholly credible – our only source of empirical grounding at the time – then certain passages remain relevant for establishing a prior. Munson warned of possible sabotage by Japanese nationals and acknowledged the existence of a few “fanatical” individuals willing to act violently on Japan’s behalf. He recommended federal control over Japanese-owned property and proposed using loyal Nisei to monitor potentially disloyal relatives. These were not the report’s focus, but they were part of it. Critics often accuse John Franklin Carter of distorting Munson’s message when advising Roosevelt. Carter’s motives are beside the point. Whether his selective quotations were the product of prejudice or caution, the statements he cited were in the report. Even if we accept Munson’s assessment in full – affirming the loyalty of Japanese American citizens and acknowledging only rare threats – the two qualifiers Carter cited are enough to undercut extreme confidence. In modern Bayesian practice, priors above 99.999% are virtually unheard of, even in high-certainty domains like particle physics and medical diagnostics. From a decision-theoretic standpoint, Munson’s own language renders such priors unjustifiable. With confidence lower than that, Roosevelt made the rational decision – clear in its logic, devastating in its consequences.

Content Strategy Beyond the Core Use Case

Posted by Bill Storage in Strategy on June 27, 2025

Introduction

In 2022, we wrote, as consultants to a startup, a proposal for an article exploring how graph computing could be applied to Bulk Metallic Glass (BMG), a class of advanced materials with an unusual atomic structure and high combinatorial complexity. The post tied a scientific domain to the strengths of the client’s graph computing platform – in this case, its ability to model deeply structured, non-obvious relationships that defy conventional flat-data systems.

This analysis is an invitation to reflect on the frameworks we use to shape our messaging – especially when we’re speaking to several audiences at once.

Everyone should be able to browse a post, skim a paragraph or two, and come away thinking, “This company is doing cool things.” A subset of readers should feel more than that.

Our client (“Company”) rejected the post based on an outline we submitted. It was too far afield. But in a saturated blogosphere where “graph for fraud detection” has become white noise, unfamiliarity might be exactly what cuts through. Let’s explore.

Company Background

- Stage and Funding: Company, with ~$30M in Series-A funding, was preparing for Series B, having two pilot customers, both Fortune-500, necessitating a focus on immediate traction. Company was arriving late – but with a platform more extensible than the incumbents.

- Market Landscape: The 2022 graph database – note graph db, as differentiated from the larger graph-computing landscape – market was dominated by firms like Neo4j, TigerGraph, Stardog, and ArangoDB. Those firms had strong branding in fraud detection, cybersecurity, and recommendation systems. Company’s extensible platform needed to stand out.

- Content Strategy: With 2–3 blog posts weekly, Company aimed to attract investors, journalists, analysts, customers, and jobseekers while expanding SEO. Limited pilot data constrained case studies, risking repetitive content. Company had already agreed to our recommendation of including employee profiles showing their artistic hobbies to attract new talent and show Company valued creative thinking.

- BMG Blog Post: Proposed to explore graph computing’s application to BMG’s amorphous structure, the post aimed to diversify content and position Company as a visionary, not in materials science but in designing a product that could solve a large class of problems faced by emerging tech.

The Decision

Company rejected the BMG post, prioritizing content aligned with their pilot customers and core markets. This conservative approach avoided alienating key audiences but missed opportunities to expand its audience and to demonstrate the product’s adaptability and extensibility.

Psychology of Content Marketing: Balancing Audiences

Content marketing must navigate a diverse audience with varying needs, from skimming executives to deep-reading engineers. Content must be universal acceptability – ensuring every reader, regardless of expertise, leaves with a positive impression (Company is doing interesting things) – while sparking curiosity or excitement in key subsets (e.g., customers, investors). Company’s audiences included:

- Technical Enthusiasts: Seek novel applications (e.g., BMG) to spark curiosity.

- Jobseekers: Attracted to innovative projects, enhancing talent pipelines.

- Analysts: Value enterprise fit, skimming technical details for authority.

- Investors: Prioritize traction and market size, wary of niche distractions.

- Customers: Demand ROI-driven solutions, less relevant to BMG.

- Journalists: Prefer relatable stories, potentially finding BMG too niche.

Strategic Analysis

Background on the graph word in 2022 will help with framing Company’s mindset. In 2017-2020, several cloud database firms had aliened developers with marketing content claiming their products would eliminate the need for coders. This strategic blunder stemmed from failure to manage messaging to a diverse audience. The blunder was potentially costly since coders are a critical group at the base of the sales funnel. Company’s rejection avoided this serious misstep but may have underplayed the value of engaging technology enthusiasts and futurists.

The graph database space was crowded. Company needed not only to differentiate their product but their category. Graph computing, graph AI, and graph analytics is a larger domain, but customers and analysists often missed the difference.

The proposed post cadence at the time, 3 to 5 posts per week, accelerated the risk of exhausting standard content categories. Incumbents like Neo4j had high post rates, further frustrating attempts to cover new aspects of the standard use cases.

Possible Rationale for Rejection and Our Responses

- Pilot Customer Focus:

- The small pilot base drove content toward fraud detection and customer 360 to ensure success and investor confidence. BMG’s niche focus risked diluting this narrative, potentially confusing investors about market focus.

- Response: Our already-high frequency of on-point posts (fraud detection, drug discovery, customer 360) combined with messaging on Company’s site ensures that an investor or analyst would unambiguously discern core focus.

- Crowded Market Dynamics:

- Incumbents owned core use cases, forcing Company to compete directly. BMG’s message was premature.

- Response: That incumbents owned core use cases is a reason to show that Company’s product was designed to handle those cases (accomplished with the majority of Company’s posts) but also had applicability beyond the crowded domains of core uses cases.

- Low ROI Potential:

- BMG targets a niche market with low value.

- Response: The BMG post, like corporate news posts and employee spotlights is not competing with core focus. It’s communicates something about Company’s minds, not its products.

- Audience Relevance:

- BMG might appeal to technical enthusiasts but is less relevant to customers and investors.

- Response: Journalists, feeling the staleness of graph db’s core messaging, might cover the BMG use case, thereby exposing Company to investors and analysts.

Missed Opportunities

- Content Diversification:

- High blog frequency risked repetitive content. BMG could have filled gaps, targeting long-tail keywords for future SEO growth.

- In 2025, materials science graph applications have grown, suggesting early thought leadership could have built brand equity.

- Thought Leadership:

- BMG positioned Company as a pioneer in emerging fields, appealing to analysts and investors seeking scalability.

- Engaging technical enthusiasts could have attracted jobseekers, addressing talent needs.

- Niche Market Potential:

- BMG’s relevance to aerospace and medical device R&D could have sparked pilot inquiries, diversifying customer pipelines.

- A small allocation of posts to niche but still technical topics could have balanced core focus without significant risk.

Decision Impact

- Short-Term: The rejection aligned with Company’s need to focus on the pilot and core markets, ensuring investor and customer confidence. The consequences were minimal, as BMG was unlikely to drive immediate high-value leads.

- Long-Term: A minor missed opportunity to establish thought leadership in a growing field, potentially enhancing SEO and investor appeal.

Lessons for Content Marketing Strategists

- Balance Universal Acceptability and Targeted Curiosity:

- Craft content that all audiences find acceptable (“This is interesting”) while sparking excitement in key groups (e.g., technical enthusiasts and futurists). Alienate no one.

- Understand the Value of Thought Leadership:

- Thought leadership shows that Company can connect knowledge to real-world problems in ways that engage and lead change.

- Align Content with Business Stage:

- Series-A startups prioritize traction, favoring core use cases. Company’s focus on financial services was pragmatic, but it potentially limited exposure.

- Later-stage companies can afford niche content for thought leadership, balancing short-term ROI with long-term vision.

- Navigate Crowded Markets:

- Late entrants must compete on established turf while differentiating. Company’s conservative approach competed with incumbents but missed a chance to reposition the conversation with visionary messaging.

- Niche content can carve unique positioning without abandoning core markets.

- Manage Content Cadence:

- High frequency (2–3 posts/week) requires diverse topics to avoid repetition. Allocate 80% to core use cases and 20% to niche topics to sustain engagement and SEO.

- Leverage Limited Data:

- With a small pilot base, anonymized metrics or hypothetical use cases can bolster credibility without revealing sensitive data. E.g., BMG simulations could serve this need.

- Company’s datasheets lacked evidential support, highlighting the need for creative proof points.

- SEO as a Long Game:

- Core use case keywords (e.g., “fraud detection”) drive immediate traffic, but keyword expansion builds future relevance.

- Company’s rejection of BMG missed early positioning in a growing field.

Conclusion

Company’s rejection of the BMG blog post was a defensible, low-impact decision driven by the desire to focus on a small pilot base and compete in a crowded 2022 graph database market. It missed a minor opportunity to diversify content, engage technical audiences, and establish thought leadership, both in general and in materials science – a field that had gained traction by 2025. A post like BMG wasn’t trying to generate leads from metallurgists. It was subtly, but unmistakably, saying: “We’re not just a graph database. We’re building the substrate for the next decade’s knowledge infrastructure.” That message is harder to convey when Company ties itself too tightly to existing use cases.

BMG was a concrete illustration that Company’s technology can handle problem spaces well outside the comfort zone of current incumbents. Where most vendors extend into new verticals by layering integrations or heuristics, the BMG post suggested that a graph-native architecture can generalize across domains not yet explored. The post showed breadth and demonstrated one aspect of transferability of success, exactly wat Series B investors say they’re looking for.

While not a critical mistake, this decision offers lessons for strategists and content marketers. It illustrates the challenge of balancing universal acceptability with targeted curiosity in a crowded market, where a late entrant must differentiate while proving traction. This analysis (mostly in outline form for quick reading) explores the psychology and nuances of the decision, providing a framework for crafting effective content strategies.

For content marketing strategists, the BMG post case study underscores the importance of balancing universal acceptability with targeted curiosity, aligning content with business stage, and leveraging niche topics to differentiate in crowded markets. By allocating a small portion of high-frequency content to exploratory posts, startups can maintain focus while planting seeds for future growth, ensuring all audiences leave with a positive impression and a few leave inspired.

Recent Comments