Archive for category Commentary

The Comet, the Clipboard, and the Knife

Posted by Bill Storage in Commentary on October 2, 2025

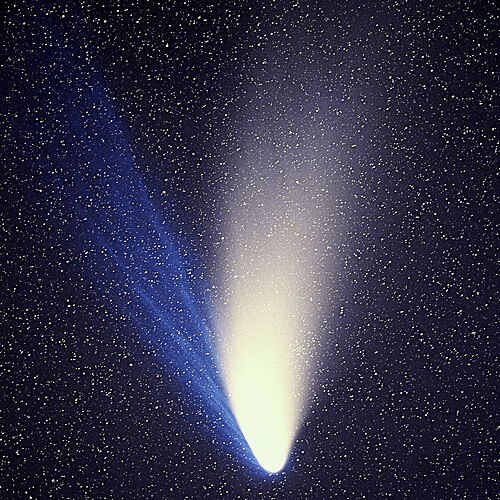

Background: My grandfather saw Comet Halley in 1910, and it was the biggest deal since the Grover Cleveland inaugural bash. We discussed it – the comet, not the inaugural – often in my grade school years. He told me of “comet pills” and kooks who killed themselves fearing cyanogens. Halley would return in 1986, an unimaginably far off date. Then out of nowhere in 1973, Luboš Kohoutek discovered a new comet, an invader from the distant Oort cloud – the flyover states of our solar system – and it was predicted to be the comet of the century. But Comet Kohoutek partied too hard somewhere near Saturn and arrived hungover, barely visible. And when Halley finally neared the sun in 1986, the earth was 180 degrees from it. Halley, like Kohoutek, was a flop. But 1996 brought Comet Hale-Bopp. Now, that was a sight even for urban stargazers. I saw it from Faneuil Hall in Boston and then bright above the Bay Bridge in San Francisco. It hung around for a year, its dual tails unforgettable. And as with anything cool, zealots stained its memory by freaking out.

A Sermon by Reverend Willie Storage, Minister of Peculiar Gospel

Brethren, we take our text today from The Book of Cybele, Chapter Knife, Verse Twenty-Three: “And lo, they danced in the street, and cut themselves, and called it joy, and their blood was upon their sandals, and the crowd applauded and took up the practice, for the crowd cannot resist a parade.”

To that we add The Epistle of Origen to the Scissors, Chapter Three, Verse Nine: “If thy member offend thee, clip it off, and if thy reason offend thee, chop that too, for what remains shall be called purity.”

These ancient admonitions are the ancestors of our story today, which begins not in Alexandria, nor the temples of Asia Minor, nor the starving castles of Languedoc, but in California, that golden land where individuality is a brand, rebellion is a style guide, and conformity is called freedom. Once it was Jesus on the clouds, then the Virgin in the sun, then a spaceship hiding behind a comet’s tail.

Thus have the ages spoken, and thus, too, spoke California in the year of our comet, 1997, when Hale-Bopp streaked across the sky like a match-head struck on the dark roof of the world. In Iowa, folk looked up and said, “Well, I’ll be damned – pass the biscuits.” In California, they looked up and said, “It conceals a spaceship,” and thirty-nine of them set their affairs in order, cut their hair to regulation style and length, pulled on black uniforms, laced up their sneakers, “prepared their vehicles for the Great Next Level,” and died at their own hands.

Now, California is the only place on God’s earth where a man can be praised for “finding himself” by joining a committee, and then be congratulated for the originality and bravery of this act. It is the land of artisan individuality in bulk: rows of identically unique coffee shops, each an altar to self-expression with the same distressed wood and imitation Edison bulbs. Rows of identically visionary cults, each one promising your personal path to the universal Next Level. Heaven’s Gate was not a freak accident of California. It was California poured into Grande-size cups and called “Enlightenment.”

Their leader, Do – once called Marshall Applewhite or something similarly Texan – explained that a spacecraft followed the comet, hiding like a pea under a mattress, ready to transport them to salvation. His co-founder, Ti, had died of cancer, inconveniently, but Do explained it in terms Homer Simpson could grasp: Ti had merely “shed her vehicle.” More like a Hertz than a hearse, and the rental period of his faithful approached its earthly terminus. His flock caught every subtle allusion. Thus did they gather, not as wild-eyed fanatics, but as the most polite of martyrs.

The priests of Cybele danced and bled. Origen of Alexandria may have cut himself off in private, so to speak, as Eusebius explains it. The Cathars starved politely in Languedoc. And the Californians, chased by their own doctrine into a corner of Rancho Santa Fe creativity, bought barbiturates at a neighborhood pharmacy, added a vodka chaser, then followed a color-coded procedure and lay down in rows like corn in a field. Their sacrament was order, procedure, and videotaped cheer. Californians, after all, enjoy their own performances.

Even the ancients were sometimes similarly inclined. Behold a relief from Ostia Antica of a stern priest nimbly handling an egg – proof, some claim, that men have long been anxious about inconvenient appendages, and that Easter’s chocolate bounty has more in common with the castrated ambitions of holy men than with springtime joy. Emperor Claudius, more clever than most, outlawed such celebrations – or tried to.

Brethren, it is not only the comet that inspires folly. Consider Sherry Shriner – a Kent State graduate of journalism and political science – who rose on the Internet just this century, a prophet armed with a megaphone, announcing that alien royalty, shadowy cabals, and cosmic paperwork dictated human destiny, and that obedience was the only path to salvation. She is a recent echo of Applewhite, of Origen, of priests of Cybele, proving that the human appetite for secret knowledge, cosmic favor, and procedural holiness only grows with new technology. Witness online alien reptile doomsday cults.

Now, California is a peculiar land which – to paraphrase Brother Richard Brautigan – draws Kent State grads like a giant Taj Mahal in the shape of a parking meter. Only there could originality be mass-produced in identical black uniforms, only there could a suicide cult be entirely standardized, only there could obedience to paperwork masquerade as freedom. The Heaven’s Gate crowd prized individuality with the same rigor that the Froot Loops factory prizes the relationship between each loop piece’s color and its flavor. And yet, in this implausible perfection, we glimpse an eternal truth: the human animal will organize itself into committees, assign heavenly responsibilities, and file for its own departure from the body with the same diligence it reserves for parking tickets.

And mark these words, it’s not finished. If the right comet comes again, some new flock will follow it, tidy as ever, clipboard in hand. Perhaps it won’t be a flying saucer but a carbon-neutral ark. Perhaps it will be the end of meat, of plastic, of children. You may call it Extinction Rebellion or Climate Redemption or Earth’s Last Stand. They may chain themselves to the rails and glue themselves to Botticelli or to Newbury Street, fast themselves to death for Mother Goddess Earth. It is a priest of Cybele in Converse high tops.

“And the children of the Earth arose, and they glued themselves to the paintings, and they starved themselves in the streets, saying, ‘We do this that life may continue.’ And a prophet among them said, ‘To save life ye must first abandon it.’”

If you must mutilate something, mutilate your credulity. Cut it down to size. Castrate your certainty. Starve your impulse to join the parade. The body may be foolish, but it has not yet led you into as much trouble as the mind.

Sing it, children.

—

All But the Clergy Believe

Posted by Bill Storage in Commentary on July 21, 2025

As the accused man approached the glowing iron, his heart pounded with faith. God, he trusted, would shield the innocent and leave the guilty to be maimed. The crowd, clutching rosaries and squinting through the smoke, murmured prayers. Most sought a miracle, some merely a verdict. They accepted the trial’s sanctity, exchanging bets on the defendant’s guilt.

Only the priest knew the fire wasn’t as hot as it looked. Sometimes it wasn’t hot at all. The iron was cooled or quietly switched. The timing of the ritual, the placement of fires and cauldrons, the priest’s step to the left rather than right. He held just enough control to steer the outcome toward justice, or what he took for it. The tricks had been passed down from the ancients. Hidden siphons, pivoting mirrors, vessels-within-vessels. Hero of Alexandria had described such things. Lucian of Samosata mocked them in his tales of string-pulled serpents and mechanical gods. Hippolytus of Rome listed them like a stage magician blowing the whistle on his rivals. Fake blood, hollow idols, the miracle of wine poured from nowhere.

By the thirteenth century, the ordeal was a dance: fire, chant, confession, absolution. The guilty, trembling at the priest’s solemn gaze, confessed before the iron’s touch. The faithful innocent, mindful of divine mercy, walked unscathed, unaware of the mirrors, the second cauldron, the cooled metal that had spared them.

There’s no record of public doubt about the mechanism, and church records support the above appraisal. Peter Leeson’s Ordeals drew data from a sample of 208 ordeals in early‑13th‑c. Várad. “Nearly two thirds of the accused were unscathed,” he wrote. F.W. Maitland, writing in 1909, found only one hot-iron ordeal in two decades that did not result in acquittal, a nearly 100% exoneration rate among the documented defendants who faced ordeals.

The audience saw a miracle and went home satisfied about heaven and earth. The priest saw the same thing and left, perhaps a faint weariness in his step, knowing no miracle had occurred. “Do not put the Lord your God to the test,” he muttered, absolving himself. No commandment had been broken, only the illusion of one. He knew he had saved the believers – from the chaos of doubt, from turning on each other, from being turned upon. It was about souls, yes. But it was more about keeping the village whole.

Everyone believed except the man who made them believe.

●

In the 1960s and 70s, the Soviet Union still spoke the language of revolution. Newspapers featured daily quotes from Lenin. Speeches invoked the inevitable collapse of capitalism and the coming utopia of classless harmony. School kids memorized Marx.

But by then – and even long before then, we later learned – no one believed it anymore. Not the factory workers, toiling under fabricated quotas. Not the schoolteachers, tasked with revising Marxist texts each summer. And the Politburo? The Brezhnevs and Andropovs mouthed slogans by day, then retreated to Black Sea dachas, Nikon cameras in hand, watching Finnish broadcasts on smuggled American TVs, Tennessee bourbon sweating on the table.

They enforced the rituals nonetheless. Party membership was still required for advancement. Professors went on teaching dialectical materialism. Writers still contrived odes to tractor production and revolutionary youth. All of it repeated with the same flat cadence. No belief, just habit and a vague sense that without it, the whole thing might collapse. No one risked reaching into the fire.

It was a system where no one believed – not the clergy, not the choir, not the congregation. But all pretended. The KGB, the Politburo, the party intellectuals, and everyone else knew Marx had failed. The workers didn’t revolt, and capitalism refused to collapse.

A few tried telling the truth. Solzhenitsyn criticized Stalin’s strategy in a private letter. He got eight years in the Gulag and internal exile. Bukovsky denounced the Communist Youth League at nineteen. He was arrested, declared insane in absentia, and confined. After release, he helped organize the Glasnost Meeting and was sent back to the asylum. On release again, he wrote against the abuse of psychiatry. Everyone knew he was right. They also knew he posed no real threat. They jailed him again.

That was the system. Sinyavsky published fiction abroad. He was imprisoned for the views of his characters. The trial was theater. There was no official transcript. He hadn’t threatened the regime. But he reminded it that its god was dead.

The irony is hard to miss. A regime that prided itself on killing God went on to clone His clergy – badly. The sermons were lifeless, the rituals joyless, the congregation compulsory. Its clergy stopped pretending belief. These were high priests of disbelief, performing the motions of a faith they’d spent decades ridiculing, terrified of what might happen if the spell ever broke.

The medieval priest tricked the crowd. The Soviet official tricked himself. The priest shaped belief to spare the innocent. The commissar demanded belief to protect the system.

The priest believed in justice, if not in miracles. The state official believed in neither.

One lied to uphold the truth. The other told the truth only when the fiction collapsed under its own weight.

And now?

If the Good Lord’s Willing and the Creek Don’t Rise

Posted by Bill Storage in Commentary on June 30, 2025

Feller said don’t try writin dialect less you have a good ear. Now do I think my ear’s good? Well, I do and I don’t. Problem is, younguns ain’t mindin this store. I’m afeared we don’t get it down on paper we gonna lose it. So I went up the holler to ask Clare his mind on it.

We set a spell. He et his biscuits cold, sittin on the porch, not sayin’ much, piddlin with a pocketknife like he had a mind to whittle but couldn’t commit. Clare looked like sumpin the cat drug in. He was wore slap out from clearing the dreen so he don’t hafta tote firewood from up where the gator can’t git. “Reckon it’ll come up a cloud,” he allowed, squinting yonder at the ridge. “Might could,” I said. He nodded slow. “Don’t fret none,” he said. “That haint don’t stir in the holler less it’s fixin ta storm proper.” Then he leaned back, tuckered, fagged-out, and let the breeze do the talkin.

Now old Clare, he called it alright. Well, I’ll swan! The wind took up directly, then down it come. We watched the brown water push a wall of dead leaves and branches down yon valley. Dry Branch, they call it, and that’s a fact. Ain’t dry now. Feature it. One minute dry as dust, then come a gully-washer, bless yer heart. That was right smart of time ago.

If you got tolerable horse sense for Appalachian colloquialism, you’ll have understood most of that. A haint, by the way, is a spirit, a ghost, a spell, or a hex. Two terms used above make me wonder if all the technology we direct toward capturing our own shreds of actual American culture still fail to record these treasured regionalisms.

A “dreen,” according to Merriam-Webster, is “a dialectal variation of ‘drain,’ especially in Southern and South Midland American English.” Nah, not in West Virginia. That definition is a perfect example of how dictionaries flatten regional terms into their nearest Standard English cousin and, in doing so, miss the real story. It’s too broad and bland to capture what was, in practice, a topographic and occupational term used by loggers.

A dreen, down home, is a narrow, shallow but steep-sided and steeply sloping valley used to slide logs down. It’s recognized in local place-names and oral descriptions. Clear out the gully – the drain – for logs and you got yourself a dreen. The ravine’s water flow, combined with exposed shards of shale, make it slick. Drop logs off up top, catch them in a basin at the bottom. An economical means for moving logs down rough terrain without a second team of horses, specialized whiffletrees, and a slip-tongue skidder. How is it that there is zero record of what a dreen is on the web?

To “feature” something means to picture it in your mind. Like, “imagine,” but more concrete. “Picture this” + “feature picture” → “feature this.” Maybe? I found a handful of online forums where someone wrote, “I can’t feature it,” but the dictionaries are silent. What do I not pay you people for?

It’s not just words and phrases that our compulsive documentation and data ingestion have failed to capture about Appalachia. Its expressive traditions rarely survive the smooshing that comes with cinematic stereotypes. Poverty, moonshine, fiddles, a nerdy preacher and, more lately, mobile meth labs, are easy signals for “rural and backward.” Meanwhile, the texture of Appalachian life is left out.

Ever hear of shape-note music? How about lined-out singing? The style is raw and slow, not that polished gospel stuff you hear down in Alabama. The leader “lines out” a hymn, and the congregation follows in a full, droning response. It sounds like a mixture of Gaelic and plain chant – and probably is.

Hill witch. Granny women, often midwives, were herbalists and folk doctors. Their knowledge was empirical, intergenerational, and somehow female-owned. They were healers with an oral pharmacopoeia rooted in a mix of Native American and Scottish traditions. Hints of it, beyond the ginseng, still pop up here and there.

Jack tales. They pick up where Jack Frost, Jack and Jill, and Little Jack Horner left off. To my knowledge, those origins are completely unrelated to each other. Jack tales use these starting points to spin yarns about seemingly low-ambition or foolish folk who outfox them what think they’re smart. (Pronounce “smart” with a short “o” and a really long “r” that stretches itself into two distinct syllables.)

Now, I know that in most ways, none of that amounts to a hill of beans, but beyond the dialect, I fear we’re going to lose some novel expressions. Down home,

“You can’t get there from here” means it is metaphorically impossible or will require a lot of explaining.

“Puny” doesn’t mean you’re small; it means you look sick.

“That dog won’t hunt” means an idea, particularly a rebuttal or excuse, that isn’t plausible.

“Tighter than Dick’s hatband” means that someone is stingy or has proposed an unfair trade.

“Come day, go day, God send Sunday” means living day to day, e.g., hoping the drought lets up.

“He’s got the big eye” means he can’t sleep.

“He’s ate up with it” means he’s obsessed – could be jealousy, could be pride.

“Well, I do and I don’t” says more than indecision. You deliver it as a percussive anapest (da-da-DUM!, da-da-DUM!), granting it a kind of rhythmic, folksy authority. It’s a measured fence-sitting phrase that buys time while saying something real. It’s a compact way to acknowledge nuance, to say, “I agree… to a point,” followed with “It’s complicated…” Use it to acknowledge an issue as more personal and moral, less analytical. You can avoid full commitment while showing thoughtfulness. It weighs individual judgment. See also:

“There’s no pancake so thin it ain’t got two sides.”

The stoics got nothin on this baby. I don’t want you think I’m uppity – gettin above my raisin, I mean – but this one’s powerful subtle. There’s a conflict between principle and sympathy. It flattens disagreement by framing it as something natural. Its double negative ain’t no accident. Deploy it if you’re slightly cornered but not ready to concede. You acknowledge fairness, appear to hover above the matter at hand, seemingly without taking sides. Both parties know you have taken a side, of course. And that’s ok. That’s how we do it down here. This is de-escalation of conflict through folk epistemology: nothing is so simple that it doesn’t deserve a second look. Even a blind hog finds an acorn now and then. Just ‘cause the cat’s a-sittin still don’t mean it ain’t plannin.

Appalachia is America’s most misunderstood archive, its stories tucked away in hollers like songs no one’s sung for decades.

Grocery Bag Facebook Covers

Posted by Bill Storage in Commentary on June 20, 2025

Kids once covered their schoolbooks with grocery bag paper, doodling on them throughout the year and collecting classmates’ comments. These covers became a slow-developing canvas of self-identity, boredom, and social standing – much like Facebook. Both blur the line between private and public, offering semi-private spaces open to public inspection. A book cover was yours but often unattended, visible to anyone nearby. Facebook hovers in the same in-between, diary and bulletin board at once.

That blur compressed identity into a single, layered plane. Book covers held class schedules, cheat notes, band logos, inside jokes, phone numbers, and the concealed name of a crush, all flattened together. Facebook’s feed mirrors this: baby photos beside political rants, memes beside job updates, a curated mess engineered for engagement. In 1986, no one called it branding, but the Iron Maiden logo or perfect Van Halen “VH” drawn on a cover was a quiet social signal – just like a profile picture or shared article today.

The social graffiti of book covers – “Call me!,” “You’re weird but cute,” “Metal rules” – anticipated Facebook’s comments and posts. Both offered tokens of attention and belonging, sometimes sincere, sometimes performative. Kids chose what to draw and whose notes to welcome, just as Facebook users filter their image through posts, likes, and bios. Each reflects a quiet negotiation of identity in public view.

Over time, both became dense with personal meaning and then, just as quickly, obsolete. A book cover ended the year torn and smudged, legible only to the one who made it. A Facebook timeline erodes too, its posts losing context, its jokes aging badly, its relationships drifting. Each fills the lulls – doodling during study hall, scrolling in a checkout line, with the detritus of distracted expression.

They’re ephemeral. Book covers were tossed or folded away with report cards and Polaroids. Facebook timelines slip backward, pixel by pixel, into the digital attic. Neither was meant to last. But for a moment, each one held a scrawl, a sticker, a lyric, something etched, then left behind. They’re the digital brown paper wrappers for an inner seventh-grader, still expressive, distracted, insecure, and trying to leave a mark before the bell rings.

NPR: Free Speech and Free Money

Posted by Bill Storage in Commentary on May 6, 2025

The First Amendment, now with tote bags – because nothing says “free speech” like being subsidized.

Katherine Maher’s NPR press release begins: “NPR is unwavering in our commitment to integrity, editorial independence, and our mission to serve the American people in partnership with our NPR Member organizations. … We will vigorously defend our right to provide essential news, information and life-saving services to the American public.” (emphasis mine)

Maher’s claim that NPR will “defend our right to provide essential news, information, and life-saving services” is an exercise in rhetorical inflation. The word “right” carries weight in American political language – usually evoking constitutional protections like freedom of speech. But no clause in the First Amendment guarantees funding for journalism. The right to speak is not the right to be subsidized.

By framing NPR’s mission as a right, Maher conflates two distinct ideas: the freedom to broadcast without interference, and the claim to a public subsidy. One is protected by law; the other is a policy preference. To treat them as interchangeable is misleading. Her argument depends not on logic but on sentiment, presenting public funding as a moral obligation rather than a choice made by legislators.

Maher insists federal funding is a tiny slice of the budget – less than 0.0001% – and that each federal dollar attracts seven more from local sources. If true, this suggests NPR’s business model is robust. So why the alarm over defunding? The implication is that without taxpayer support, NPR’s “life-saving services” will vanish. But she never specifies what those services are. Emergency broadcasts? Election coverage? The phrase is vague enough to imply much while committing to nothing.

The real issue Maher avoids is whether the federal government should be funding media at all. Private outlets, large and small, manage to survive without help from Washington. They exercise their First Amendment rights freely, supported by subscriptions, ads, or donations. NPR could do the same – especially since its audience is wealthier and more educated than average. If its listeners value it, they can pay for it.

Instead of making that case, Maher reaches for historical authority. She invokes the Founding Fathers and the 1967 Public Broadcasting Act. But the founders, whatever their views on an informed citizenry, did not propose a state-funded media outlet. The Public Broadcasting Act was designed to ensure editorial independence – not guarantee permanent federal funding. Appealing to these sources lends NPR an air of legitimacy it should not need, and cannot claim in this context.

Then there’s the matter of bias. Maher praises NPR’s “high standards” and “factual reporting,” yet sidesteps the widespread perception that NPR leans left. Dismissing that concern doesn’t neutralize it – it feeds it. Public skepticism about NPR’s neutrality is a driving force behind calls for defunding. By ignoring this, Maher doesn’t just miss the opposition’s argument – she reinforces it, confirming the perception of bias by acting as if no other viewpoint is worth hearing.

In the end, Maher’s defense is a polished example of misdirection. Equating liberty with a line item is an argument that flatters the overeducated while fooling no one else. She presents a budgetary dispute as a constitutional crisis. She wraps policy preferences in the language of principle. And she evades the real question: if NPR is as essential and efficient as she claims, why can’t it stand on its own?

It is not an attack on the First Amendment to question public funding for NPR. It is a question of priorities. Maher had an opportunity to defend NPR on the merits. Instead, she reached for abstractions, hoping the rhetoric would do the work of reason. It doesn’t.

I’m Only Neurotic When You Do It Wrong

Posted by Bill Storage in Commentary on October 6, 2025

I don’t think of myself as obsessive. I think of myself as correct. Other people confuse those two things because they’ve grown comfortable in a world that tolerates sloppiness. I’m only neurotic when you do it wrong.

In Full Metal Jacket, Stanley Kubrick mocks the need for precision. Gunnery Sergeant Hartman, played by R. Lee Ermey, has a strict regimen for everything from cellular function on up. Kubrick has Hartman tell Private Pyle, “If there is one thing in this world that I hate, it is an unlocked footlocker!” Of course, Hartman hates an infinity of things, but all of them are things we secretly hate too. For those who missed the point, Kubrick has the colonel later tell Joker, “Son, all I’ve ever asked of my Marines is that they obey my orders as they would the word of God.”

The facets of life lacking due attention to detail are manifold, but since we’ve started with entertainment, let’s stay there. Entertainment budgets dwarf those of most countries. All I’ve ever asked of screenwriters is to hire historical consultants who can spell anachronism. Kubrick is credited with meticulous attention to detail. Hah. He might learn something from Sgt. Hartman. In Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon duel scene, a glance over Lord Bullingdon’s shoulder reveals a map with a decorative picture of a steam train, something not invented for another fifty years. The scene of the Lyndon family finances shows receipts bound by modern staples. Later, someone mentions the Kingdom of Belgium. Oops. Painterly cinematography and candlelit genius, yes – but the first thing that comes to mind when I hear Barry Lyndon is the Dom Pérignon bottle glaring on the desk, half a century out of place.

Soldiers carry a 13-star flag in The Patriot. Troy features zippers. Braveheart wears a kilt. Andy Dufresne hides his tunnel behind a Raquel Welch poster in Shawshank Redemption. Forrest Gump owns Apple stock. Need I go on? All I’ve ever asked of filmmakers is that they get every last detail right. I’m only neurotic when they blow it.

Take song lyrics. These are supposedly the most polished, publicly consumed lines in the English language. Entire industries depend on them. There are producers, mixers, consultants galore – whole marketing teams – and yet no one, apparently, ever said, “Hold on, Jim, that doesn’t make any sense.

Jim Morrison, I mean. Riders on the Storm is moody and hypnotic. On first hearing I settled in for what I knew, even at twelve, was an instant classic. Until he says of the killer: “his brain is squirming like a toad.” Not the brain of a toad, not a brain that toaded. There it was – a mental image of a brain doing a toad impression. The trance was gone. Minds squirm, not toads. Toads hold still, then hop, then hold still again. Rhyming dictionaries existed in 1970. He could have found anything else. Try: “His mind was like a dark abode.” Proofreader? Editor? QA department? Peer review? Fifty years on, I still can’t hear it without reliving my early rock-crooner trauma.

Rocket Man surely ranks near Elton’s John’s best. But clearly Elton is better at composition than at contractor oversight. Bernie Taupin wrote, “And all this science, I don’t understand.” Fair. But then: “It’s just my job, five days a week.” So wait, you don’t understand science, but NASA gave you a five-day schedule and weekends off because of what skill profile? Maybe that explains Challenger and Columbia.

Every Breath You Take by The Police. It’s supposed to be about obsession, but Sting (Sting? – really, Gordon Sumner?) somehow thought “every move you make, every bond you break” sounded romantic. Bond? Who’s out there breaking bonds in daily life? Chemical engineers? Sting later claimed people misunderstood it, but that’s because it’s badly written. If your stalker anthem is being played at weddings, maybe you missed a comma somewhere, Gordon.

“As sure as Kilimanjaro rises like Olympus above the Serengeti,” sings Toto in Africa. Last I looked, Kilimanjaro was in Tanzania, 200 miles from the Serengeti. Olympus is in Greece. Why not “As sure as the Eiffel Tower rises above the Outback”? The lyricist admitted he wrote it based on National Geographic photos. Translation: “I’m paid to look at pictures, not read the captions.”

“Plasticine porters with looking glass ties,” wrote John Lennon in Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds. Plasticine must have sounded to John like some high-gloss super-polymer. But as the 1960s English-speaking world knew, Plasticine is a children’s modeling clay. Were these porters melting in the sun? No other psychedelic substances available that day? The smell of kindergarten fails to transport me into Lennon’s hallucinatory dream world.

And finally, Take Me Home, Country Roads. This one I take personally. John Denver, already richer than God, sat down to write a love letter to West Virginia and somehow imported the Blue Ridge Mountains and Shenandoah River from Virginia. Maybe he looked at an atlas once, diagonally. The border between WV and VA is admittedly jagged, but at least try to feign some domain knowledge. Apologists say he meant blue-ridged mountains or west(ern) Virginia – which only makes it worse. The song should have been called Almost Geographically Adjacent to Heaven.

Precision may not make art, but art that ignores precision is just noise with a budget. I don’t need perfection – only coherence, proportion, and the occasional working map. I’m not obsessive. I just want a world where the train on the wall doesn’t leave the station half a century early. I’ve learned to live among the lax, even as they do it all wrong.

anachronism, entertainment, film, films, humor, movies, music

3 Comments