Posts Tagged music

Dugga Dugga Dugga

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Art, speleology on December 30, 2025

This story is about the band Wire and about using electric hammer drills in caves. That’s why I called this site The Multidisciplinarian. Not because I’m competent in many disciplines, or because I harbor disciplinarians in the basement, but because I wanted a single conversational space where unrelated things could bump into each other and see what happens. That’s what early bloggers did. Not Jorn Barger in 1997, when he coined the hideous word “blogging.” I’m still recovering. I mean the nineteenth-century social diarists. People made public diaries: Here’s my thoughts, see what you think. Beatrice Webb, aptly named, ran what was essentially a Victorian blog when she wasn’t co-founding the London School of Economics. If this social diary bores you, skip to the end and watch the 3-minute video.

I used to write record reviews for a couple of magazines. I was bad at it. I quit in frustration after reading what struck me as a devastatingly concise review of a Pere Ubu album. Pere Ubu, for the uninitiated, was an avant-garage band from northern Ohio who were far more popular on other continents than in Cleveland. Or even trendy Kent, Ohio.

The reviewer wrote something like this:

David Thomas, Ubu’s singer, though many people disputed that what he did qualified as singing, is coming from wherever Jim Morrison was heading. Pere Ubu is what Roxy Music would have been if Eno had taken over, fired Bryan Ferry, and hired a neurotic poet.

David Thomas, incidentally, later used several of my photos. Twenty years on, he told me he was thrilled that I’d captured what appear to be the only known photos of classic-era Pere Ubu, the brief and unrepeatable moment when Mayo Thompson and Richard Thompson, from opposite ends of the musical universe, were both in the band. Here’s two I took at the Cleveland Agora, after Thomas told security to let me in with a telephoto.

I remember thinking I could never write a review that clever. The writer, maybe Dean Suzuki, now a music professor at San Francisco State, nailed it. These days, the review impresses me slightly less. The Morrison line doesn’t really explain anything beyond “Thomas is weirder than Morrison.” You might infer that Morrison was a rock singer drifting toward the avant-garde, while Thomas was an avant-garde noise artist drifting toward rock. That’s clever, but it wouldn’t have helped me decide whether to buy The Art of Walking.

The Roxy Music comparison works better. Pere Ubu, like Roxy, made songs. They both layered noise and oddity onto them. But the key difference, the reason the “neurotic poet” line lands, is Thomas’s vocal delivery. He’s been described as yelping, barking, warbling like a distressed whale, or like a nervous art-school guy about to puke or cry. It’s stream-of-consciousness paranoia set to rhythm inside a foundry.

For readers already familiar with early Roxy Music (I discussed here), the analogy signals freaky, Eno-era art rock taken to an extreme, minus the glamour. That might hook you. But it works better as enticement than guidance. As criticism, it dodges the two questions I was supposed to answer. Was the band’s objective worth pursuing? And did they succeed?

Anyway, this piece isn’t about Pere Ubu or The Art of Walking. It’s about Wire and the art of cave exploration. The Pere Ubu detour is just throat-clearing. Amy, a caving friend, once said of my music criticism, “Once a critic, always an ass.” Fair enough.

Wire formed in London in October 1976. The members met at art school and had little prior band experience or instrumental proficiency. They were beginners leaning hard into punk’s DIY ethos. Unlike many of their contemporaries, who pursued deconstruction, Wire practiced pure reductionism. Not the Sex Pistols’ kind. Something colder and more deliberate.

From the start, their influences were eclectic: 60s pop, early Pink Floyd, Roxy Music, Brian Eno, krautrock, and punk, selectively. The Ramones for brevity, not for attitude. Wire always had internal tension between a pop impulse and an experimental or noise impulse. As Colin Newman put it, “Wire’s never really shared much taste as a band. It’s about the work. It always has been.” The tension proved unsustainable. They split in 1979.

So when Wire reappeared in 1986, touring with no advance press, it was a shock. They played none of their early material. Old Wire songs were two-minute punk bursts for intellectuals. New Wire played twenty- to thirty-minute trance pieces. What began as a rehearsal exercise became their most durable experiment. There are now roughly a hundred versions of “The Drill,” first released on the Snakedrill EP.

The band described it as monophonic, mono-rhythmic repetition. Then they translated it for the rest of us: “dugga dugga dugga.” Relentless single-line loops. Call and response. “Drill, drill, drill.” “Dugga, dugga, dugga.”

We’re milling through the grinder, and grinding through the mill,

If this is not an exercise, could it be a…

Could it be a…

…

Sometimes that unfinished line repeats long enough that you’re shouting “drill!”. Then it goes on so long you forget why you cared. Occasionally they finish the sentence. Sometimes they don’t. Drill. It’s an acquired taste.

Now I’ll describe this like a mechanical engineer who knows audio physics and a bit of music theory, but is resolved that he will never write engaging music critique.

Although “The Drill” sits nominally in 4/4, its rhythmic surface has virtually no accentuation of downbeat or tactus. You hear an isochronous pulse stream with no hierarchy. No dynamics. No phrasing cues. Meter becomes something you infer rather than perceive. The pulse just is.

Terse, right? Take that, Dean Suzuki. Who is, by the way, a very cool guy.

In 1990, Wire released The Drill, nearly an hour long, nine radically different versions of the same piece. Disco-adjacent versions, near-electronica, a sprawling twelve-minute live Chicago take, instrumentals like “Jumping Mint” and “Did You Dugga?” No sane producer would rush such a thing to market.

Also in 1990, I bought a 36-volt Hilti TE-10A battery-powered hammer drill. A Hilti dealer delivered it to my house in a red Hilti truck, which felt important. It was expensive and brutally heavy. Spare batteries were unthinkable, both for weight and cost. John Ganter and I used it for aid climbs underground. As far as I know, it was the first electric hammer drill used for cave exploration in West Virginia. The artifact now lives in John’s farmhouse garage, or museum.

That drill changed everything. On one battery you could place ten 3/8 x 3-inch wedge anchors. In hours you could do what had previously taken weeks with Rawl star drills or self-drives that barely engaged an inch of rock. Abuse followed, of course. Bolt farms sprouted. Some pristine pits gathered unnecessary hardware because someone thought they knew better than the last person. Alabama had already shown us the future.

Still, the potential was undeniable. When I returned to caving in 2021, Amy had a Bosch GBH18V-21. Drills were now lighter, and batteries were small and affordable. We had lists of high leads. We placed 108 bolts in a couple of months, none of them superfluous. Hunter, Casey, and Kyle, working the same cave, were bolting across ceilings, opening ridiculous routes.

Then Kyle, Max, Casey, and I started hauling drills through hours of low-airspace passages to climb beyond sumps. The drill became standard gear. You divided up the gear and double-dry-bagged it. And you brought earplugs. Ninety seconds of drilling in a confined space is wicked loud. Dugga dugga dugga.

On the drive to the cave, Max, Amy, and I traded Spotify tracks. I submitted “The Drill.” Not everyone’s taste, but it grows on you. Its flat pulse stream pairs well with the experience of standing in a swinging etrier, helmet lamp glaring, arm fully extended, ropes and gear tangling, water dripping down your back, mud in your eye. You are wearing goggles, right?

I started wondering whether actual drill audio could be mashed up with Wire’s “The Drill.” In theory, drill noise should be broadband, mostly non-harmonic. In practice, you hear pitch. A steady rotational component plus a reciprocating hammering component creates tonal structure.

I had helmet-cam footage, so I ran Fourier analysis. Once upon a time this required oscilloscopes and lab gear. Now software like Mixxx does it for free. Surprisingly, my Bosch drill consistently produces a dominant pitch around D#4, about 311 Hz. Hunter’s drilling hits the same pitch. Either we push identically, or push force doesn’t affect impact rate much. The advertised hammer rate is 5,100 BPM, or 85 Hz. The fourth harmonic lands near 340 Hz. Our load pulls it down roughly a semitone.

Our Milwaukee M12 rotary hammers center closer to C, with a hammer rate of 4,400 BPM, or 73 Hz. We push it harder than Milwaukee recommends. Otherwise it’s too slow. No motors have died yet. Its fourth harmonic is around 293 Hz. Analysis shows strong components at C3 and C4. We’re dragging it down a major second plus a bit.

DJs and the like probably do this in their sleep, or Mixxx does it for them. I made a spreadsheet. Wire’s Chicago “Drill” sits near D# minor. The A Bell Is a Cup version is in A minor. “Jumping Mint” is in C. I transposed everything to A, matched tempos, pitched the Bosch drill accordingly, then stitched audio and video together in DaVinci Resolve.

The six-minute version is reserved for future live drill events. Here’s the short cut. You might like it. Especially if you’ve ever enjoyed Pere Ubu’s singing or the sound of a machine shop.

Roxy Music and Forgotten Social Borders

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Art on August 20, 2025

In the early 1970s rock culture was diverse, clannish and fiercely territorial. Musical taste usually carried with it an entire identity, including hair length and style, clothing – including shoes/boots – politics, and which record stores you could haunt. King Crimson, Yes, Pink Floyd, and Emerson, Lake & Palmer belonged to the progressive end of the spectrum.

By the early 1970s, progressive rock (prog, as shorthand began to appear in music press) was musical descriptor and social signal. Calling a band “progressive” implied a certain seriousness, technical sophistication, and intellectual ambition. It marked a listener as someone who prized virtuosity, complexity, and concept albums over pop singles. The label carried subtle class and educational connotations: prog fans were expected to appreciate classical references, odd time signatures, extended solos, and experimental studio techniques. King Crimson was often called avant-garde rock, though Henry Cow deserved the label much more. ELP was called symphonic rock, Pink Floyd was psychedelic rock, and Yes was Epic rock – but they were all prog. And listening to all this stuff made you smart. Or pretentious.

Across the divide, the early 70s saw greaser rock and the emerging ’50s nostalgia circuit. Sha Na Na, the sock-hop revival, the idea that a gold lamé suit was a passport to a simpler age ushered in the Happy Days craze and its music. Few people straddled those camps. A Crimson devotee wouldn’t admit to liking Sha Na Na if he wanted to keep his dignity. Rock music was attitude, self-image, and worldview.

Into that landscape stepped Roxy Music in 1972, and they were utterly bewildering. Bryan Ferry came dressed like a lounge lizard from a time-warped jukebox, crooning with a sincerity that clearly wasn’t parody or caricature. Still, it was far too stylized to be mere mimicry. His band conjured a storm of dissonant non-keyboard electronics, angular rhythms, and Brian Eno’s futuristic treatments. Roxy Music embraced rather than mocked the early rock gestures of Elvis’s era. Ferry gave listeners permission to take Jerry Lee Lewis seriously, even reverently. Lewis was suddenly an avant-garde icon, pounding the keys with the same abandon that Eno applied to his electronics (witness Richard Trythall’s 1977 musique concrète: Omaggio a Jerry Lee Lewis).

That was the radicalism of early Roxy Music, which cannot be grasped retrospectively, even by the most avid young musicologist. Roxy dissolved the borders that the tribes of 1972 held sacred. They showed that ’50s rock, glam stylization, and avant-garde electronics could coexist in an unstable but persistent alloy. The shock of that is hard to grasp from today’s vantage point, when music is not tied to identity and “classic-rock” Roxy Music is remembered for Ferry’s Avalon-era suave crooning.

Oddly, and I think almost uniquely, as the band moved mainstream over the next fifteen years, the noisy, Eno-era chaos was retroactively smoothed into the same brand identity as Avalon. For later fans, there was no sharp rupture; the old chaos was domesticated and folded back into the same style sensibility.

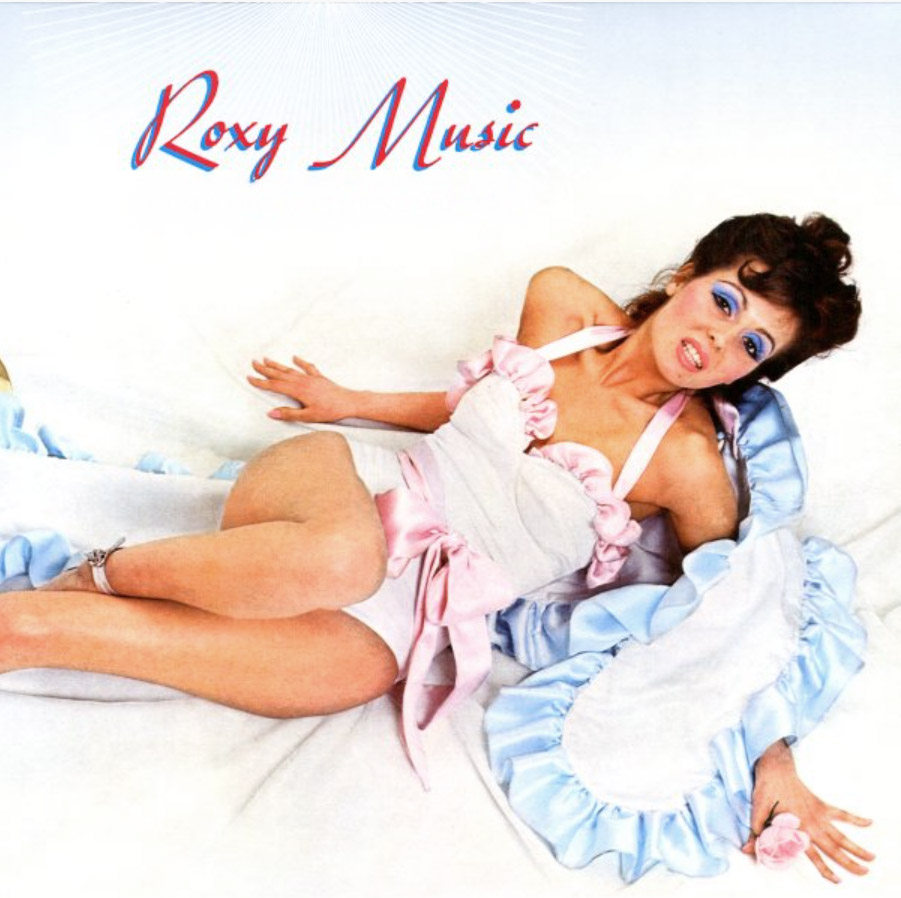

But the rupture had existed. Their cover art reinforced it. Roxy Music (1972) with Kari-Ann Muller posing like a mid-century pin-up, was tame in skin exposure compared to H.R. Giger’s biomechanical nudity on ELP’s Brain Salad Surgery. The boldness of Roxy Music’s cover lay in context, not ribaldry. The sleeve was bluntly terrestrial. For a prog listener used to studying a Roger Dean landscape on a first listen of a new Yes album, Roxy Music surely seemed an insult to seriousness.

When Fleetwood Mac reinvented themselves in 1975, new listeners treated it as rebirth. The Peter Green blues band that authored Black Magic Woman and the Buckingham–Nicks hit machine lived in separate mental compartments. Very few Rumours-era fans felt obliged to revisit Then Play On or Kiln House, and most who did saw them as curiosities. Similarly, Genesis underwent a hard split. Its listeners did not treat Foxtrot and Invisible Touch as facets of a single project.

Roxy Music’s retrospective smoothing is almost unique in rock. Their chaos was polished backward into elegance. The Velvet Underground went the other way. At first their noise was cultish, even disposable. But as the legend of Reed, Cale, and Nico grew, the past was recoded as prophecy. White Light/White Heat became the seed of punk. The Velvet Underground & Nico turned into the Bible of indie rock. Even Loaded – a deliberate grab for radio play, stripped of abrasion – was absorbed into the myth and remembered as avant-garde. It wasn’t. But the halo of the band’s legend bled forward and made every gesture look radical.

Roxy Music remains an oddity. The suave Avalon listener in 1982 could put on Virginia Plain without embarrassment and believe that those early tracks were nearby on a continuum. Ferry’s suave sound bled backward and redefined the chaos. He retroactively re-coded the Eno-era racket. The radical rupture was smoothed out beneath the gloss of brand identity.

That’s why early Roxy is so hard to hear as it was first heard. In 1972 it was unclassifiable, a collision of tribes and eras. To grasp it, you have to forget everything that came after. Imagine a listener whose vinyl shelf ended with The Yes Album, Aqualung, Tarkus, Ash Ra Tempel, Curved Air, Meddle, Nursery Cryme, and Led Zeppelin IV. Sha Na Na was a trashy novelty act recycling respected antiques – Dion and the Belmonts, Ritchie Valens, Danny and the Juniors. Disco, punk, new wave? They didn’t exist.

Now, in that silence, sit back and spin up Ladytron.

I’m Only Neurotic When You Do It Wrong

Posted by Bill Storage in Commentary on October 6, 2025

I don’t think of myself as obsessive. I think of myself as correct. Other people confuse those two things because they’ve grown comfortable in a world that tolerates sloppiness. I’m only neurotic when you do it wrong.

In Full Metal Jacket, Stanley Kubrick mocks the need for precision. Gunnery Sergeant Hartman, played by R. Lee Ermey, has a strict regimen for everything from cellular function on up. Kubrick has Hartman tell Private Pyle, “If there is one thing in this world that I hate, it is an unlocked footlocker!” Of course, Hartman hates an infinity of things, but all of them are things we secretly hate too. For those who missed the point, Kubrick has the colonel later tell Joker, “Son, all I’ve ever asked of my Marines is that they obey my orders as they would the word of God.”

The facets of life lacking due attention to detail are manifold, but since we’ve started with entertainment, let’s stay there. Entertainment budgets dwarf those of most countries. All I’ve ever asked of screenwriters is to hire historical consultants who can spell anachronism. Kubrick is credited with meticulous attention to detail. Hah. He might learn something from Sgt. Hartman. In Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon duel scene, a glance over Lord Bullingdon’s shoulder reveals a map with a decorative picture of a steam train, something not invented for another fifty years. The scene of the Lyndon family finances shows receipts bound by modern staples. Later, someone mentions the Kingdom of Belgium. Oops. Painterly cinematography and candlelit genius, yes – but the first thing that comes to mind when I hear Barry Lyndon is the Dom Pérignon bottle glaring on the desk, half a century out of place.

Soldiers carry a 13-star flag in The Patriot. Troy features zippers. Braveheart wears a kilt. Andy Dufresne hides his tunnel behind a Raquel Welch poster in Shawshank Redemption. Forrest Gump owns Apple stock. Need I go on? All I’ve ever asked of filmmakers is that they get every last detail right. I’m only neurotic when they blow it.

Take song lyrics. These are supposedly the most polished, publicly consumed lines in the English language. Entire industries depend on them. There are producers, mixers, consultants galore – whole marketing teams – and yet no one, apparently, ever said, “Hold on, Jim, that doesn’t make any sense.

Jim Morrison, I mean. Riders on the Storm is moody and hypnotic. On first hearing I settled in for what I knew, even at twelve, was an instant classic. Until he says of the killer: “his brain is squirming like a toad.” Not the brain of a toad, not a brain that toaded. There it was – a mental image of a brain doing a toad impression. The trance was gone. Minds squirm, not toads. Toads hold still, then hop, then hold still again. Rhyming dictionaries existed in 1970. He could have found anything else. Try: “His mind was like a dark abode.” Proofreader? Editor? QA department? Peer review? Fifty years on, I still can’t hear it without reliving my early rock-crooner trauma.

Rocket Man surely ranks near Elton’s John’s best. But clearly Elton is better at composition than at contractor oversight. Bernie Taupin wrote, “And all this science, I don’t understand.” Fair. But then: “It’s just my job, five days a week.” So wait, you don’t understand science, but NASA gave you a five-day schedule and weekends off because of what skill profile? Maybe that explains Challenger and Columbia.

Every Breath You Take by The Police. It’s supposed to be about obsession, but Sting (Sting? – really, Gordon Sumner?) somehow thought “every move you make, every bond you break” sounded romantic. Bond? Who’s out there breaking bonds in daily life? Chemical engineers? Sting later claimed people misunderstood it, but that’s because it’s badly written. If your stalker anthem is being played at weddings, maybe you missed a comma somewhere, Gordon.

“As sure as Kilimanjaro rises like Olympus above the Serengeti,” sings Toto in Africa. Last I looked, Kilimanjaro was in Tanzania, 200 miles from the Serengeti. Olympus is in Greece. Why not “As sure as the Eiffel Tower rises above the Outback”? The lyricist admitted he wrote it based on National Geographic photos. Translation: “I’m paid to look at pictures, not read the captions.”

“Plasticine porters with looking glass ties,” wrote John Lennon in Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds. Plasticine must have sounded to John like some high-gloss super-polymer. But as the 1960s English-speaking world knew, Plasticine is a children’s modeling clay. Were these porters melting in the sun? No other psychedelic substances available that day? The smell of kindergarten fails to transport me into Lennon’s hallucinatory dream world.

And finally, Take Me Home, Country Roads. This one I take personally. John Denver, already richer than God, sat down to write a love letter to West Virginia and somehow imported the Blue Ridge Mountains and Shenandoah River from Virginia. Maybe he looked at an atlas once, diagonally. The border between WV and VA is admittedly jagged, but at least try to feign some domain knowledge. Apologists say he meant blue-ridged mountains or west(ern) Virginia – which only makes it worse. The song should have been called Almost Geographically Adjacent to Heaven.

Precision may not make art, but art that ignores precision is just noise with a budget. I don’t need perfection – only coherence, proportion, and the occasional working map. I’m not obsessive. I just want a world where the train on the wall doesn’t leave the station half a century early. I’ve learned to live among the lax, even as they do it all wrong.

anachronism, entertainment, film, films, humor, movies, music

3 Comments