Life of Constantine

Understanding Constantine the Great is essential for interpreting this monument, which includes a pictorial narrative of an episode in his life one might call a turning point in western history.

According to the panegyric by Eusebius of Caesarea – his Life of Constantine – Constantine was born in Moesia (modern Serbia) around 27 February 272 (or possibly 273). His dating rests on imperial propaganda: Eusebius [i]asserts he reigned for about 32 years and lived at least twice as long as Alexander the Great. But virtually all of his dates are disputed, and Eusebius’s text is both unfinished (he died around 339) and deeply apologetic.

Constantine was the son of the western tetrarch Constantius Chlorus and Helen (later venerated as a saint). Early in his life he spent time at the court of Galerius – likely as a “pledge of good conduct” on his father’s behalf rather than a true hostage[ii]. He later joined his father in Britain [iii]and was present when Constantius died on 25 July 306 at York, whereupon Constantine’s troops proclaimed him Augustus.

In 307 he set aside his earlier concubine (or partner) Minervina [iv] – mother of his son Crispus – and married Fausta, daughter of the former Emperor Maximian[v] This marriage tied him into the imperial family and sharpened his rivalry with his brother-in-law, Maxentius, whose death at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in 312 left Constantine leader of the western empire.

That battle marks the locus classicus of Constantine’s conversion narrative. According to Lactantius, on the eve of battle he was instructed in a dream to mark his soldiers’ shields with the “sign of Christ.” He describes the sign as being the Christian chi-rho[vi] symbol, now known as the Constantinian monogram, although pre-Christian uses of the symbol are certain. Eusebius, writing some 25 years later, describes a cross of light in the sky, the words “En touto Nika” (“In this sign, conquer”), and a personal visitation by Christ[vii]. Many scholars treat these accounts as carefully constructed propaganda. (Eusebius’s agenda is obvious.)

Was Constantine converted in that moment? The older view says yes. The modern view argues he remained essentially pagan until his deathbed baptism. Inspecting the evidence suggests both views oversimplify. The best summary is that Constantine’s engagement with Christianity was gradual and ambiguous: early Christian leanings appear alongside traditional ritual, but a sudden “Eureka” conversion is unlikely. (His late baptism, common in his cultural milieu, does not mean he was insincere[viii].)

His religious policy reflects this complexity[ix] [x]. In 313 he and Licinius agreed to mutual toleration of religions (commonly labelled the “Edict of Milan,” though the actual text is elusive). Pagan groups such as the Manichaeans may have been excluded[xi].

Even after the time of his reported conversion, he seemed to have maintained interest in Sol Invictus and Hercules; some degree of syncretization is plausible[xii]. Constantine’s exact position cannot be drawn from ancient texts or inscriptions. The reason for this is not merely that ancient sources are not trustworthy. Elliott illustrates that Constantine skillfully maintained neutral or ambiguous language in public propaganda even after the Christian writers (who preferred the view that he underwent a momentous conversion) report that he was fully committed to a Christian mission[xiii]. Eusebius credits Constantine with ordering wholesale temple-destruction and crushing pagan priests – yet scholars like H. A. Drake and Thomas Elliott argue he did not pursue a coherent anti-pagan campaign of the sort later attributed to him[xiv] [xv]. Constantine’s 323 decree that Christians were banned from participation from state sacrifices (Codex Theodosianus 16.2.5) might have pleased the clergy, but must also be counted technically as a restriction on religious freedom[xvi].

By 315-324 Constantine was engaged in civil war with his brother-in-law Licinius (married to his half-sister Constantia, after what was likely a false charge by Constantine of an attempt on his life by Licinius[xvii]. A truce that lasted a few years and included provisions for sons of both emperors to be Caesars. After breakdown of this truce and two major battles, Constantine emerged as the sole ruler of the Roman world.

Licinius fled from the final battleground, Chrysopolis, to Nicomedia. Both Constantia and Eusebius pled on Licinius’s behalf; and Constantine agreed, guaranteeing safe conduct to Thessalonica. A few months later, coincidentally just after dispatch of the invitations to bishops for the first Council of Nicaea, Licinius and his son were both murdered.The final battle was at Chrysopolis (324), after which Constantine became sole ruler of the Roman world. The sources say Constantia and Eusebius interceded on Licinius’s behalf, but a few months later Licinius and his son were executed – showing, once again, the mixture of familial tie and brutal politics.

At the First Council of Nicaea (325) Constantine sought to stabilize the church, though he admitted publicly (according to some sources) that he failed to grasp the finer points of the Arian controversy.

On April 1, 326, Constantine issued a comprehensive edict on sexuality and morality that was unprecedented in the history of Rome. It made adultery, having concubines and elopement capital offenses punishable by specific and cruel deaths. Nurses who facilitated elopement, for example, would have molten lead poured down their throats. As Timothy Barnes[xviii] eloquently distills it, “this law disregards the natural appetites of men and women in favor of an abstract ideal of purity deduced from Christian tenets of asceticism [and] rendered criminal the normal behavior of many Roman aristocrats.” The law immediately became a tool of Romans seeking elimination of any personal or political opponent against whom a shred of evidence of indiscretion could be laid. Constantine’s decorated son Crispus, consul and Caesar became its victim. The specific accusation is lost to history, but legend – and uncritical modern histories – hold that it involved an attempted rape of Fausta, his stepmother. This seems unlikely, based on geography alone; they lived many days travel from each other. Constantine sentenced his son to death, and Crispus was executed immediately.

Helena convinced Constantine of Crispus’s innocence, possibly pointing out that Fausta had an obvious motive for elimination of the heir, Crispus; and Fausta’s death soon followed, either by execution or by suicide. Helena’s famous pilgrimage to the holy land was no doubt a component of a program to replace public images of the Crispus/Fausta scandal with those more fitting to Christianity’s imperial champion.

Despite such examples, it’s inaccurate to say that Constantine generally made sweeping changes to Roman government favoring Christian beliefs. In some cases, he continued programs begun by Diocletian. His opinions and legislation vacillated, often granting mass amnesties. Suppression of paganism and incorporation of the Christian agenda into Roman government took decades, with a major milestone being the prohibition of all things pagan under Theodosius.

The two primary sources on the final period of Constantine’s reign give accounts that cannot remotely be reconciled. The pagan Eunapius[xix], who claims Christians contributed to Alaric’s invasion of Greece, sees him as bumbling, lacking strategy, and imposing ruinous taxes[xx]; Eusebius sees him as a charitable and wise hero. Both agree that he provided increased financial and legislative support to Christians until his death in May, 337.

Eusebius reports that Constantine was baptized in Nicomedia weeks before he died. Jerome’s translation of Vita added that it was the Arian bishop, Eusebius of Nicomedia, who performed the baptism. Other writers placed the baptism early, at around 312[xxi]. Orthodox Christianity’s anxiety over the notion that Constantine was baptized by a heretic bishop seems to have given rise to ancient fictional accounts of the baptism[xxii].

Constantine’s life may forever remain controversial. Ancient biographies are all marred by strong political and religious (pagan or Christian) bias[xxiii]. Ancient authors had both means and the motive for introducing fictions. Medieval and modern writers – even those with no such bias – reproduced these fictions, and thus they persist. Only in the last few decades has critical analysis been applied toward the goal of extracting the real Constantine from propaganda, myth and legend. What seems to emerge is a figure who, during his 32-year reign, despite violent impulses and frequent reversals and self-contradictions, managed to continue the growth of commerce begun under Diocletian, maintain Rome’s military and its borders, and restore a sense of unity in the wake of long years of internal conflict. His critics and proponents agree that Constantine also sought, for reasons about which there is great disagreement, to convert the empire to Christianity; and that this quest profoundly influenced the course of human history.

The Arch and Its History

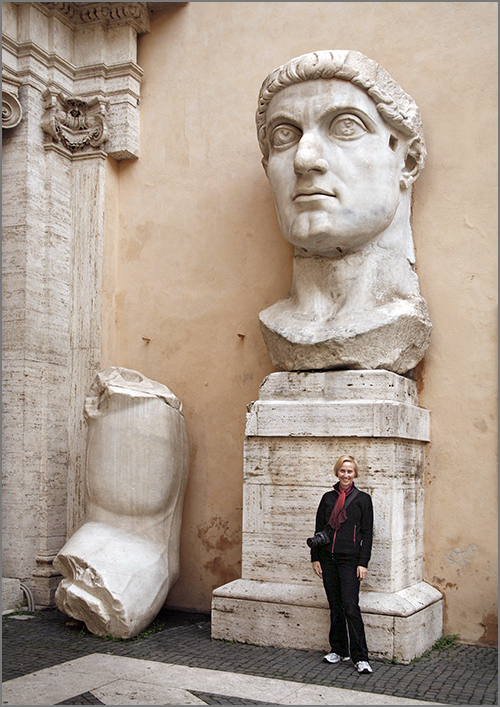

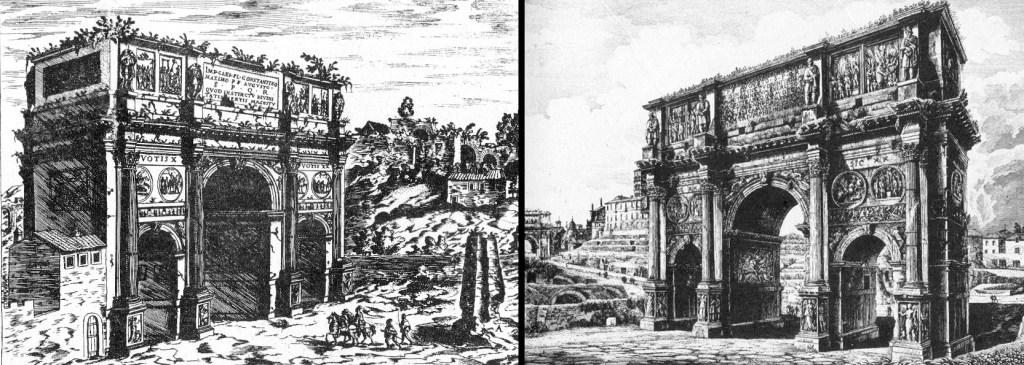

No ancient sources mention the Arch of Constantine or any arch at its present location. It first appears in sixteenth-century engravings by Du Pérac and later in works by Piranesi, Rossini, Lauro, and others. In modern literature, Rodolfo Lanciani (1892) described the arch and located it at the intersection of the Via Sacra and the Via Triumphalis, beside the Colosseum. Platner’s Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome (1920s) discussed the arch in detail, noting that the name Via Triumphalis lacks historical basis. He also dated its completion to 315–316, based on the mention of the decennalia in the inscriptions of the side arches. Of course, the arch need not be the same age as its inscriptions, which only imply the decennalia through the phrase votis X. Still, this date has been accepted by nearly all modern writers. The nearby inscription votis XX – an ancient equivalent of “many happy returns”– foretells the emperor’s vicennalia ten years ahead.

Scholars once speculated that the arch itself might date from the time of Domitian or Hadrian. That theory fell out of favor in the 1930s but was revived in the 1990s by Alessandra Melucco Vaccaro. Recent material analyses, however, have firmly dated the structure to the fourth century, settling the question first raised by Arthur Frothingham in 1912.

The arch is about 20 meters high (excluding any ornamentation that may once stood atop it), 25 meters wide, and 7 meters deep. The central passage rises 12 meters; the two side passages, 7 meters. Eight fluted Corinthian columns of yellow Numidian marble, likely taken from a Flavian-era building, are attached decoratively to the arch – seven of them original. One is a modern replica, replacing the column removed by Pope Clement VIII in 1597 and now standing in San Giovanni in Laterano. The columns are purely ornamental and bear no structural load.

While some sculptural elements were carved specifically for Constantine, most of the decoration can be traced confidently to earlier imperial monuments. This reuse wasn’t random, as the word spolia might suggest. The selections appear deliberate, chosen for their suitability to Constantinian propaganda– a point first emphasized by Hans Peter L’Orange.

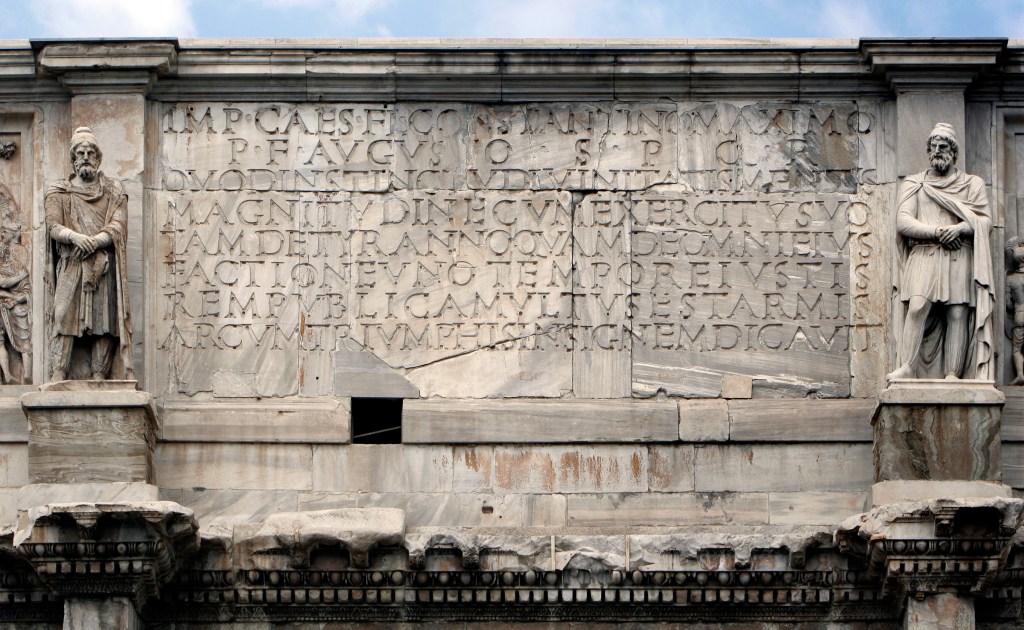

Identical inscriptions appear on both sides of the arch:

IMPERATORI CAESARI FLAVIO CONSTANTINO MAXIMO

PIO FELICI AVGVSTO SENATVS POPVLVSQVE ROMANVS

QVOD INSTINCTV DIVINITATIS MENTIS

MAGNITVDINE CVM EXERCITV SVO

TAM DE TYRANNO QVAM DE OMNI EIVS

FACTIONE VNO TEMPORE IVSTIS

REMPVBLICAM VLTVS EST ARMIS

ARCVM TRIVMPHIS INSIGNEM DICAVIT

To the Emperor Caesar Flavius Constantinus, the Greatest,

pious, fortunate, the Senate and people of Rome,

by inspiration of divinity and his own great mind,

with his righteous arms,

against both the tyrant and his faction,

at one time, in rightful battle,

he avenged the Republic,

and dedicated this arch as a memorial to his triumphs.

The phrase INSTINCTV DIVINITATIS, unknown in any surviving text before the arch was built, has puzzled readers ever since. Interpretations range from “prompted by a divinity” (pagan or Christian) to “inspired by divinity” in a more abstract sense. A close parallel, instinctus divinus, occurs in Cicero’s De divinatione, where it refers to foreknowledge of coming events – a meaning that fits well here. Constantine knew the passage and quoted from the same work in his speech Ad sanctorum coetum. The inscription likely reflects both Christian and pagan nuances, while also boasting that Constantine foresaw the need to deal with Maxentius and acted decisively to restore order. In the same speech where he cites Cicero, Constantine interprets a Sibylline prophecy in Christian terms[xxiv], revealing the blend of traditions behind this careful ambiguity.

The marble blocks that hold the inscription, and those facing the rest of the arch, vary irregularly in type and color – a feature unseen in earlier imperial monuments and strong evidence of a fourth-century construction. Likewise, the poor alignment of pre-carved components, noted by Mark Jones, would have been unthinkable in the Hadrianic or Domitianic periods. A striking example is the discontinuity in the entablature’s decoration where blocks join.

Red – Trajan; Yellow – Marcus Aurelius; Blue – Hadrian;

Green – Constantine and Licinius or Constantius

The eight Dacian captives that stand across the attic, proud and solemn (below), probably came from Trajan’s Forum, whose great frieze is discussed below. Their style dates them to the late Domitianic or Trajanic era, since they clearly depict Dacians. Carved in pavonazzetto marble, similar statues have been found in Trajan’s Forum, including one now displayed in the Vatican’s Braccio Nuovo. One Dacian (no. 7) is a modern (1731–32) replica; the others have restored hands and feet.

The Attic Panels

Most scholars agree that the eight rectangular relief panels in the attic were taken from an earlier monument dedicated to Marcus Aurelius. Whether those panels were ever set in place on such a monument is unknown; there’s no numismatic or literary evidence for its existence. Arthur Frothingham argued that at least two different arches supplied the panels, one of them dedicated to Lucius Verus, Marcus Aurelius’s co-emperor for part of his reign. He identified two distinct styles in the panels – one more Hellenistic, the other more Roman in character. Max Wegner reached a similar conclusion, calling the two styles klassischer Meister and barocker Meister[xxv].

In arguing for a Verus origin, Frothingham[xxvi] noted that the rightmost panel of the north side (panel 4) shows a standard bearing two portraits, while the matching south panel shows only one. He took the double-portrait standard as evidence for a dual dedication, and the single-portrait one as Verus alone, reasoning that Verus, whose arch stood on the Via Appia, had been the key ruler in the Parthian war. He also pointed to two distinct frame designs, suggesting they must have come from separate arches. He dismissed the simpler explanation – that multiple sculptor teams were given different frame dimensions. Frothingham’s work illustrates the hazards of early archaeological enthusiasm and the tendency to leap from observation to hypothesis.

While his conclusions were hasty and thinly defended, Frothingham made several original and useful observations later adopted by other scholars. His argument identifying Verus as the single-standard emperor doesn’t hold, but eliminating it doesn’t rule out the possibility that the panels came from two monuments of Marcus Aurelius, one more inclusive of his somewhat lesser partner. Against this view, all eight panels share identical external dimensions – an unlikely coincidence if made for different arches. Modern scholars acknowledge differences in style but attribute them to variation among sculptors rather than to different monuments.

Commodus was also proposed as the original subject of the panels[xxvii], but that seems unlikely. One scene – the liberalitas panel discussed below – shows clear evidence of his removal, consistent with the damnatio memoriae imposed after his death. Whoever the original subjects were, all now represent Constantine. The current Constantine heads were replaced in 1732[xxviii], probably as restorations of earlier re-carvings. Three additional panels, thought to be from the same series (suggesting a lost arch of Marcus Aurelius with at least twelve panels[xxix]), are now in the Capitoline Museum. Johannes Sieveking concluded that those three came from an earlier monument than the panels now on Constantine’s arch, a view accepted by some but not all modern scholars. Their dimensions are identical to those on the arch.

Art historians have long debated the exact dates of the attic panels based on style and content. All agree they belong to the reign of Marcus Aurelius, though not on precise years. Attempts to date them stylistically seem to me overconfident, ignoring the obvious: several artists likely worked concurrently, each with different techniques. Most scholars place the panels between 176 and 180 CE.

I. S. Ryberg[xxx] and others suggested that the attic panels should be “read” in sequence, wrapping around the arch in the same direction as the continuous Constantinian frieze below. This seems improbable, since the panels are only a subset of their original series. It also strains belief that events in Constantine’s life would so neatly parallel those of Marcus Aurelius as to preserve a coherent narrative after re-carving the heads.

Scholars now generally assign the following subjects to the panels:

| Location | Scene |

| North face, panel 1 | Adventus |

| North face, panel 2 | Profectio |

| North face, panel 3 | Liberalitas (Largitio/Congiarium) |

| North face, panel 4 | Clementia (Submissio/Justitia) |

| South face, panel 1 | Rex Datus |

| South face, panel 2 | Prisoners brought before the emperor |

| South face, panel 3 | Adlocutio |

| South face, panel 4 | Lustratio |

The Adventus panel likely depicts the return of Marcus Aurelius from his campaign against the Germans and Sarmatians in 176. P. G. Hamberg[xxxi] called the scene “allegorical,” a term that irritated Karl Lehmann[xxxii]. Hamberg’s reasoning was that Marcus is the only mortal figure, though the setting – the Temple of Fortuna Redux on the Via Latia in the Campus Martius – was real. The focus is the interaction between Marcus and Roma[xxxiii] on the right; Mars stands behind the emperor, and Victory flies above his head. The war is over.

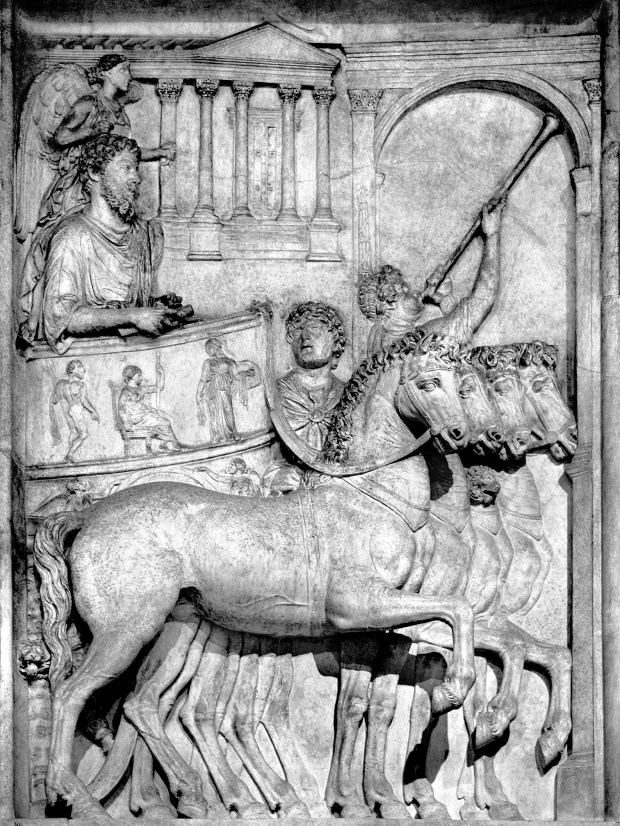

The Adventus is paired with a Profectio scene, showing Marcus departing for battle in 169. He wears a short tunic and mantle, his right heel lifted in motion. A reclining personification of the Via Flaminia bids him farewell. The identification of the road is secure – similar scenes appear on coins labeled with the road’s name. Virtus, dressed for travel, contrasts with Roma, who typically bares one breast. A bearded Genius Senatus stands behind Marcus. To his left stands Claudius Pompeianus, his son-in-law and advisor, barely visible. Earlier scholars, including Stuart Jones[xxxiv] and Eugénie Sellers Strong[xxxv], identified this figure as Bassaeus Rufus, though Pompeianus is generally accepted today. Wegner classed this relief as klassischer in style, though the treatment of soldiers and horses hardly supports that. L’Orange identified the structure in the scene as the Arch of Domitian in the Campus Martius, crowned with a chariot drawn by elephants.

The third panel on the north face depicts an act of public largess, likely the Liberalitas of 177, celebrating the joint victory of Marcus and Commodus the year before. Pompeianus appears, but Commodus does not. A conspicuous void probably marks where he once sat beside his father; a fragment of his foot remains on the podium. The lower half of the toga of a standing figure is carved in shallower relief than the upper, inconsistent with natural weathering. Several heads are restorations, and the head of a boy riding piggyback is missing. The recarved area’s surface is noticeably rougher than the rest. Commodus, the target of a damnatio memoriae, also appears to have been erased from one of the Capitoline panels, where he appears to have been removed from the chariot.

Panel four, Clementia, shows Marcus seated on a tall stool (sella castrensis), Pompeianus at his side, surrounded by soldiers bearing flags and standards. Two barbarian prisoners stand before him – an old man and a young boy supporting him. Many interpret this as a defeated chieftain and his son submitting in grief. This panel also bears traces of Commodus’s erasure: on the central imago standard, the lower portrait has been chiseled away while the upper survives intact. Eric Varner noted that the lost figure seems to have worn a general’s cloak (paludamentum), suggesting, as Wegner did, that the portraits originally depicted Marcus and Commodus, with the latter deliberately removed.

The south face begins with the Rex Datus scene, in which a vassal king is either crowned or introduced before Roman soldiers – signifying peace and alliance. Giovanni Bellori[xxxvi], writing in 1690, identified the emperor as Trajan. Frothingham argued for Lucius Verus, noting that coins of Verus but not Marcus bear the legend Rex Armeniis Datus. The absence of the king’s attendants may simply reflect lack of space. The king’s head is a modern restoration.

South face panel two shows enemy soldiers brought before the emperor in the field, marked by a tree on the right. One captive still resists, the other submits. The emperor, in tunic, paludamentum, and leggings, is accompanied by Pompeianus. The panel has been broken and repaired.

The Adlocutio scene shows the emperor addressing his troops before a campaign. His right hand is raised; his missing left likely held a lance. Seven soldiers, each in distinct armor – scale, chain, and otherwise – listen intently. The upper section, including the standards’ tops, is a restoration.

Finally, Lustratio depicts a ritual purification before battle. The emperor presides over sacrifices of a bull, sheep, and pig – the suovetaurilia – to purify the land before Mars. Soldiers with flags stand behind a musician and an incense-bearer (camillus). Pompeianus appears again behind the emperor. The upper quarter of the panel, showing wreaths and the eagle-topped standard, is a restoration. The portrait on the left imago is too weathered for identification. Art historians often debate this panel’s style, most agreeing it represents a later and more modern turn than the other seven.

Remnants of the Great Trajanic Frieze

Most scholars agree that the four large reliefs, each made up of two panels about three meters high, were once part of a roughly 30-meter-long frieze from the Forum of Trajan. Two are on the short ends of the attic; the other two, better preserved and more vivid, are inside the central arch, nearly at ground level. Most authorities identify the original subject as Trajan and date the work to the early Hadrianic period. Others argue for Domitian, suggesting that these reliefs somehow survived his damnatio memoriae – as the Cancelleria reliefs did – through chance or political expediency. A standing objection to the Trajanic origin theory is that the Forum of Trajan was reportedly still intact in Theodoric’s day, long after Constantine’s arch had been erected.

The western relief shows Trajan on horseback, his mantle caught in the wind, towering above a fallen Dacian who cowers beneath him. Another Dacian kneels in front, pleading for clemency that we know will be granted. To Trajan’s left, an armored Roman seems on the verge of cutting the captive’s throat. Trajan himself is bare-headed, his participation in battle symbolic rather than literal. Similar scenes appear in later Roman art, such as the third-century Ludovisi Sarcophagus, where unhelmeted emperors preside over the chaos of war. The inscription above reads Liberatori Urbis – Liberator of the City.

The relief on the opposite side of the central bay compresses two distinct episodes – adventus and battle – into a single image. Trajan stands between Roma (or perhaps Virtus) and Victory, who raises a wreath to crown him. Behind them, Roman cavalry trample the wavy-haired Dacians. Diana Kleiner notes that this fusion of triumphal entry and combat is unprecedented in earlier imperial art, though similar compositional liberties appear in contemporary works[xxxvii]. The inscription above this scene reads Fundatori quietis – Founder of Peace.

The Trajanic reliefs on the ends of the attic also depict the Dacian wars that concluded in 106. The east side shows buglers, mounted Romans, and several falling or fallen Dacians. The west side captures an ambush, emphasizing the futility of the Dacians’ crude weapons against Roman discipline and technology.

The Roundels of Hadrian and Constantine

Eight circular reliefs, each about 2.4 meters across, decorate the north and south faces of the Arch. Each roundel has a slightly flattened bottom – probably an adjustment made during construction to fit them more neatly beneath the inscriptions above. This suggests they weren’t originally carved for the Arch itself. Mark Wilson Jones proposes that the distortion shows the builders prioritized structural symmetry over artistic integrity, though a simpler explanation might be a last-minute measurement error on a rushed job[xxxviii].

A facing of porphyry marble, a material not used on earlier imperial monuments, still surrounds one pair of roundels. Where the porphyry is missing, the masonry behind it has been hacked away, leading some to argue that the Arch was repurposed in Constantine’s time. But that damage only shows that the roundels weren’t part of the Arch’s first design. They may have been added late in construction, or their intended position may have changed before installation.

Early twentieth-century scholars like Sieveking and Stuart Jones[xxxix] once thought the roundels dated to the Flavian period and had been recut under Claudius Gothicus[xl]. Their arguments collapsed once scholars identified Antinous – Hadrian’s companion – in one of the hunting scenes. The association with Hadrian’s love of hunting quickly settled the matter. Those same early critics claimed the north and south roundels were carved by different artists, but Margarete Bieber[xli] showed that the apparent differences could be explained by weathering and biological growth on the marble.

Most now agree that Hadrian was the original subject of the roundels. The later recut heads are too weathered to identify with certainty, but Constantine seems the obvious replacement, with some possibly reworked into portraits of his relatives or allies. Constantius Chlorus and Licinius have both been proposed, the latter more convincingly.

The first roundel on the north face shows a boar hunt, with Antinous at upper left and Constantine’s head recut over Hadrian’s. The second shows a sacrifice to Apollo, perhaps featuring Constantius or Licinius. The third roundel depicts a lion hunt, again possibly Licinius, while the fourth shows a sacrifice to Hercules, whom Constantius claimed as an ancestor. A small figure of Victory appears beside Hercules.

On the south side – acknowledging that their current order may differ from the original – the first roundel shows departure for a hunt. The second depicts a sacrifice to Silvanus. The third and fourth show a bear hunt and sacrifice to Diana, respectively.

The two roundels on the short east and west ends differ markedly from the others. Their circular form is unaltered, and their style is distinct. Early art historians were quick to dismiss these as inferior works by less-skilled Constantinian sculptors. Modern scholars are more cautious: the change in style reflects shifting artistic conventions, not necessarily decline. Still, there’s good reason to think that the overall craftsmanship of Constantine’s builders – especially in structure – was less exacting than their predecessors.

On the east face, the relief shows Sol in his four-horse chariot. On the west, Luna rides her two-horse biga. The Luna panel sits above a section of the large Constantinian frieze showing Constantine’s son Crispus in triumph. Some have read this arrangement symbolically: Crispus as the moon reflecting the light of his father, the sun. Bill Thayer wryly notes the irony – the moon, once full, inevitably wanes to nothing, as did Crispus[xlii].

The Frieze of Constantine

Despite the inscription’s boast of Constantine’s victories, the Arch is not truly a triumphal monument. Constantine never claimed a triumph after defeating Maxentius in civil war, and the frieze reflects that restraint. It shows a sequence of historical scenes, but none of the formal rituals of triumph. The blocky figures, repetitive gestures, and compressed action have long been dismissed as signs of artistic decline, yet they may reflect deliberate choices – an emerging visual language that emphasized clarity and symbolism over classical naturalism.

The frieze runs continuously around the lower level of the Arch, above the side passageways. It highlights key moments in Constantine’s career before and after his victory over Maxentius.

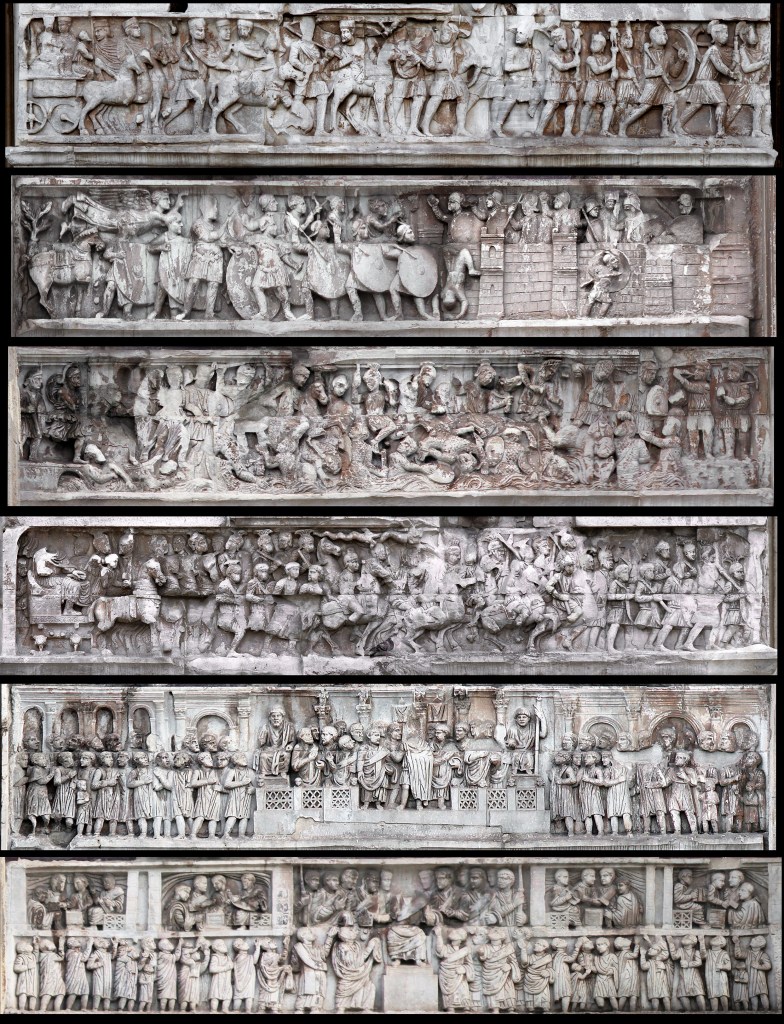

It begins on the west side, near the Palatine Hill, with Constantine departing Milan to confront Maxentius (1st row in below image). He rides in his chariot at the head of the procession: soldiers march beside him, some in helmets, others wearing Pannonian caps. A camel and a horse appear among the ranks, along with musicians and imaginifers – standard bearers carrying images of the emperor.

The next episode, on the south side, shows the siege of a walled city – probably Verona (2nd row). Victory crowns Constantine, whose head is mostly lost, while his soldiers repel defenders hurling stones and spears. One defender tumbles from the ramparts as a lone Roman scales the wall. Here, Constantine towers over his men, nearly twice their height, in one of the earliest imperial uses of hierarchical scale – a convention more familiar from early Christian art than earlier Roman state reliefs.

The next scene (row 3) depicts the climactic Battle of the Milvian Bridge. The victory is already assured: Victory and Virtus stand as witnesses, while Constantine’s enemies drown in the Tiber below. The emperor himself once appeared in a boat beside the river god at the lower left, but that portion is now missing. At the right edge of the panel, musicians celebrate the triumph (not shown).

The short east side, badly eroded, shows Constantine entering Rome (row 4). It is a ceremonial arrival, not a triumph. He sits on a throne as part of a quadriga, greeting the city that is now his.

The north frieze begins with Constantine addressing the citizens of Rome from the Rostra (row 5). He stands frontally at the center, the only figure to face the viewer directly. Surrounded by men in togas, he dominates the composition, radiating authority. This new visual rhetoric—the emperor as a remote, enthroned dominus – marks a turning point. It anticipates later portrayals of Christ Pantocrator, and scholars continue to debate[xliii] whether that resemblance is coincidental or consciously shaped by such imperial imagery.

Architectural details anchor the setting. To the left stands the Basilica Julia; to the right, the Arch of Septimius Severus. Five columns rise behind the Rostra, likely from Diocletian’s Decennalia monument. Two statues flank Constantine: Marcus Aurelius, seated and draped, on his left; Hadrian, bearded and holding a globe, on his right. The message is explicit – Constantine aligns himself with Rome’s philosopher-emperors, not with the tetrarchs who preceded him. Three boys appear in the scene, an unusual feature in imperial reliefs, perhaps alluding to Constantine’s three sons and the return of dynastic succession.

The final scene (last row) mirrors the liberalitas panel of Marcus Aurelius. Constantine, enthroned at the center (his head now missing), distributes gifts to the people. The composition – central ruler, surrounding attendants, recipients reaching upward – strongly recalls early Christian images of Christ enthroned among the apostles. Whether by design or intuition, the emperor’s image and that of the divine overlapped here for the first time in Roman monumental art. Constantine holds a tessera for coin distribution, dropping money into the toga of a senator gazing up in gratitude. Four smaller panels along the borders depict clerks recording the distribution—bureaucracy in marble, empire as administration as much as power.

Other Constantinian Art

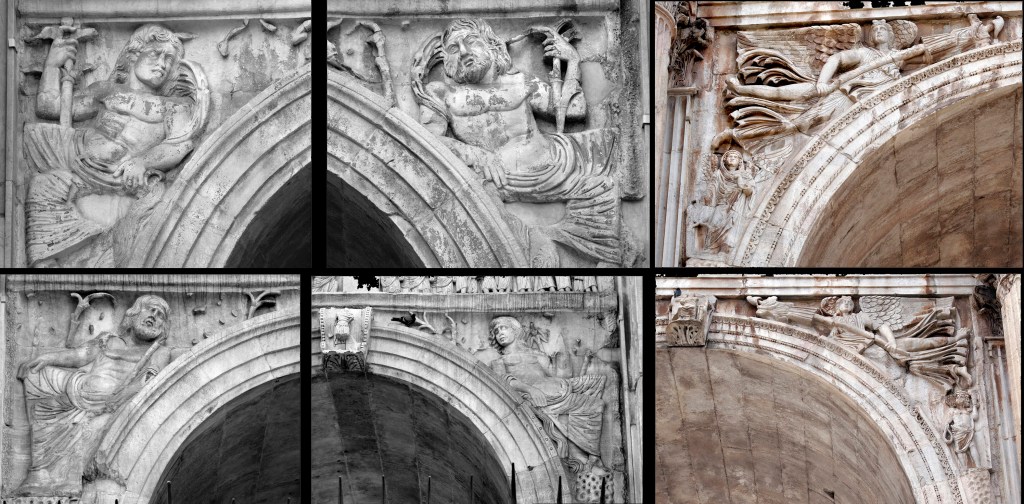

The spandrels above the central and side arches contain reliefs carved into the arch after it was already erected. Four images of Victory (below), each paired with a different seasonal genius, adorn the main arch. The side bays feature spandrels with river gods in various poses.

The socles (below) are decorated with familiar themes: captives led by Roman soldiers and Victories overseeing the enemy. L’Orange linked some of these pedestal scenes to specific enemy armies. Weathering, mold, and the protective fencing now enclosing the arch make detailed observation difficult.

Structural Proportion Models

The influence of numerical ratios on ancient architecture and literature is often understated. Scholars who study dimensions in monuments sometimes see patterns that may not have been intended[xliv], yet there is evidence of careful proportional design at the Arch of Constantine.

Mark Wilson Jones analyzed its dimensions in detail. He notes, for example, that column heights match the axial width of the flanks, the height of the main passageway imposts, and the intercolumniation of the central arch within tolerances for similar features. Ratios of 2:1, 3:1, and 3:4 recur throughout the structure: column bases are half their height above ground, the entablature is half the monument’s length, column height is one-third of the length, and the width of the lateral arches is two-thirds that of the central arch. Most of these ratios hold within about one percent. Readers who enjoy arithmetic elegance in ancient monuments should consult Mark Wilson Jones for full analyses[xlv].

More Information

For those interested in Constantine’s life, a warning is in order: nearly all sources – ancient or modern – carry Christian or anti-Christian bias. Reconstructing his biography requires skepticism, careful weighing of sources, and critical synthesis. A few recommended works include:

- Constantine and Eusebius (1981) by Timothy D. Barnes

- Constantine and the Bishops: The Politics of Intolerance (2002) by H. A. Drake

(Barnes and Drake reach very different conclusions, which itself is instructive.) - Constantine (2005), edited by Samuel N. C. Lieu and Dominic Montserrat

- Life of Constantine (Vita Constantina), Eusebius, with introduction by Averil Cameron and Stuart Hall

For direct engagement with the sources, the prolegomena of Ernest Cushing Richardson’s 1890 translation of Vita Constantina is invaluable and freely available online at the Christian Classics Ethereal Library.

Many books on Roman ruins and art discuss the Arch of Constantine. Footnotes on this page list some, but several classic art history texts are now outdated. Among current works, two stand out:

- Roman Sculpture (Yale Publications in the History of Art, 1994) by Diana E. E. Kleiner

(A comprehensive, readable guide that avoids the usual obfuscation found in art history prose.) - Mutilation and Transformation: Damnatio Memoriae and Roman Imperial Portraiture (2004) by Eric R. Varner

Footnotes

[i] Eusebius, Vita Constantini 1.8 and 4.53

[ii] Zonaras, Compendium of History 12.33

[iii] Lactantius De Mortibus Persecutorum Ch. 24. Fletcher translation available online at the Christian Classics Ethereal Library.

[iv] Whether wife or mistress is disputed, and is the subject of many modern papers.

[v] Panegyrici Latini 6 (ed. Baehrens, Mynors)

[vi] Lactantius De Mortibus Persecutorum, Ch. 44. Roberts/Donaldson translation available online at the Christian Classics Ethereal Library

[vii] Eusebius, Vita Constantina 1. 28-29

[viii] Delayed baptism was common, given the belief held by some Christians that major forgiveness was divinely granted only once (pre-baptism), and thus it does not indicate a lack of commitment to Christianity

[ix] T.D. Barnes Constantine and Eusebius Cambridge, Mass. 1981. ISBN-13: 978-0674165311.

[x] Thomas G. Elliott “Constantine’s Conversion: Do We Really Need It?” Phoenix, Vol. 41, No. 4. (Winter, 1987), pp. 420-438.

[xi] Manicheanism is specifically addressed as being banned in the Codex Theodosianus, although in chapters attributed to Valentinian and Valens.

[xii] I am not citing pagan imagery on coinage as a basis for this. Baynes (Constantine the Great and the Christian Church, 1972, ISBN-13: 978-0197256725) and others have shown that coin imagery is not a reliable indicator of the emperor’s beliefs.

[xiii] Thomas G. Elliott “The Language of Constantine’s Propaganda,” Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974 – ), Vol. 120. (1990), pp. 349-353

[xiv] H. A. Drake. Book Review: “Constantine and Eusebius”, The American Journal of Philology, Vol. 103, No. 4. (Winter, 1982), p. 464.

[xv] H. A. Drake. Constantine and the Bishops: The Politics of Intolerance, The John Hopkins University Press, 2000. Drake’s evidence for intentional ambiguity in Constantine’s propaganda stands, regardless of the validity of his analogy between ancient Rome and modern governments, and the scathing criticism of his work by Barnes.

[xvi] See Michele R. Salzman’s “‘Superstitio’ in the Codex Theodosianus and the Persecution of Pagans” (Vigiliae Christianae, Vol. 41, No. 2. Jun., 1987, pp. 172-188) for a discussion of apologetics/polemics and the gradual transition under Constantine from tolerance of paganism to persecution of it.

[xvii] Anonymous (Anonymi Valesiani) Origo Constantini Imperatoris Ch. 5

[xviii] T.D. Barnes. Constantine and Eusebius Cambridge, Mass. 1981, p.220.

[xix] Eunapius, as brought forth by Zosimus, Historia Nova

[xx] Zosimus and Aurelius Victor (Epitome de Caesaribus 41.16) agree on this point.

[xxi] Fowden, Garth “The Last Days of Constantine: Oppositional Versions and Their Influence,” The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 84. (1994), pp. 146-170.

[xxii] Conversio Constantini in the Actus Sylvestr. The book, Il battesimo di Costantino il Grande. Storia di una scomoda ereditby Marilena Amerise, (Hermes Zeitschrift fr klassische Philologie, Einzel-schriften, Heft 95) examines this at length. Timothy Barnes strongly challenges the scholarship of this book. Jan Willem Drijvers is less negative but finds its main argument unconvincing. Both reviewers agree that the topic warrants more investigation.

[xxiii] While it is inaccurate to say that there was no distinction between religion and politics in late imperial times, it is worth noting that the boundary was less solid and drawn differently than today’s separation from church and state in modern government.

[xxiv] Linda Jones Hall reads the same evidence as indicating intentional ambiguity: “Cicero’s instinctu divino and Constantine’s instinctu divinitatis : The Evidence of the Arch of Constantine for the Senatorial View of the “Vision” of Constantine”. Journal of Early Christian Studies 6.4 (1998) pp. 647-671.

[xxv] Wegner, M. Archologischer Anzeige,. 1938 col. 155.

[xxvi] A. L. Frothingham. “Who Built the Arch of Constantine? III.” The Attic, American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 19, No. 1. (Jan. – Mar., 1915), pp. 1-12.

[xxvii] M. Cagiano de Azevedo citation in Eric. R. Varner: Mutilation and Transformation. Damnatio Memoriae and Roman Imperial Portraiture. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2004. ISBN: 90-04-13577-4.

[xxviii] Sydney Dean, Editor. Journal of American Archaeology. July-December, 1920. Archaeological News reports that in Bulletino della Commissione archeologica comunale di Roma, C. Gradara published an excerpt for the diary of Pietro Bracci in which Bracci states that he carved new heads for the emperors and other figures in the attic reliefs, along with new heads and hands for seven of the Dacian captives and one completely new Dacian.

[xxix] As reported by Platner in his topic on Arcus Constantini.

[xxx] Inez Scott Ryberg. Panel Reliefs of Marcus Aurelius (Monographs on archaeology and the fine arts, 14) 1967. ASIN: B0006BQ1JW

[xxxi] Per Gustaf Hamberg Studies in Roman Imperial Art Almquist, Uppsala 1945,ASIN: B0007IWWTM

[xxxii] Karl Lehmann Review of Studies in Roman Imperial Art, in The Art Bulletin, Vol. 29, No. 2. (Jun., 1947), pp. 136-139.

[xxxiii] Jocelyn Toynbee maintains that this god is Virtus, not Roma, on the basis that Roma stays in Rome while Virtus accompanies the emperor to war, bringing him home victorious. J. M. C. Toynbee. Review: Panel Reliefs of Marcus Aurelius The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 58, Parts 1 and 2. (1968), pp. 293-294.

[xxxiv] H. Stuart Jones. Notes on Roman Historical Sculptures Papers of the British School at Rome, III, 1906. pp 213-271.

[xxxv] Eugenie Sellers Strong (Mrs. Arthur Strong) Roman Sculpture from Augustus to Constantine, Duckworth and Co. London 1907 reprinted by Hacker Art Books, New York, 1971, ISBN-13: 978-0878170531.

[xxxvi] G.P. Bellori Veteres Arcus Augustorum Triumphis Insignes Ex reliquiis quae Romae adhuc supersunt cum imaginibus triumphalibus restituti. Rome, Jacopo de Rossi, 1690.

[xxxvii] Diana E. E. Kleiner. Roman Sculpture. Yale University Press, 1994. ISBN-13: 978-0300059489. Kleiner differentiates this conflation from the continuous documentary style of the Column of Trajan.

[xxxviii] Mark Wilson Jones. “Genesis and Mimesis: The Design of the Arch of Constantine in Rome.” The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 59, No. 1. (Mar., 2000), pp. 50-77.

[xxxix] H. Stuart Jones “The Relief Medallions of the Arch of Constantine,” Papers of the British School at Rome, Vol. III. MacMillan & Co., 1906. pp. 216-271.

[xl] Claudius Gothicus did have a number of Flavian sculptures recut in his likeness. Constantine declared himself to be the grandson of Claudius Gothicus

[xli] M Bieber. Mitteilungen des Deutshen Archaeologischen Instituts, Roemische Abteilung. 1911, p. 214.

[xlii] Bill Thayer. Crispus: the Moon at her Full. http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Gazetteer/Places/Europe/Italy/Lazio/Roma/Rome/Arch_of_Constantine/W.html.

[xliii] Jas Elsner. Imperial Rome and Christian Triumph: The Art of the Roman Empire AD 100-450. 1999. ISBN-13: 978-0192842657

[xliv] See for example Richard Brilliant’s bizarre proposal for a geometric design scheme for the Arch of Septimius Severus, which involves dozens of intersecting arcs.

[xlv] Mark Wilson Jones. See note 43. Also: “Principles of Design in Roman Architecture: the setting out of centralized buildings,” Papers of the British School at Rome 57. 1989.

Photos and text copyright 2025 by William K Storage

Recent Comments