Posts Tagged art

Roxy Music and Forgotten Social Borders

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Art on August 20, 2025

In the early 1970s rock culture was diverse, clannish and fiercely territorial. Musical taste usually carried with it an entire identity, including hair length and style, clothing – including shoes/boots – politics, and which record stores you could haunt. King Crimson, Yes, Pink Floyd, and Emerson, Lake & Palmer belonged to the progressive end of the spectrum.

By the early 1970s, progressive rock (prog, as shorthand began to appear in music press) was musical descriptor and social signal. Calling a band “progressive” implied a certain seriousness, technical sophistication, and intellectual ambition. It marked a listener as someone who prized virtuosity, complexity, and concept albums over pop singles. The label carried subtle class and educational connotations: prog fans were expected to appreciate classical references, odd time signatures, extended solos, and experimental studio techniques. King Crimson was often called avant-garde rock, though Henry Cow deserved the label much more. ELP was called symphonic rock, Pink Floyd was psychedelic rock, and Yes was Epic rock – but they were all prog. And listening to all this stuff made you smart. Or pretentious.

Across the divide, the early 70s saw greaser rock and the emerging ’50s nostalgia circuit. Sha Na Na, the sock-hop revival, the idea that a gold lamé suit was a passport to a simpler age ushered in the Happy Days craze and its music. Few people straddled those camps. A Crimson devotee wouldn’t admit to liking Sha Na Na if he wanted to keep his dignity. Rock music was attitude, self-image, and worldview.

Into that landscape stepped Roxy Music in 1972, and they were utterly bewildering. Bryan Ferry came dressed like a lounge lizard from a time-warped jukebox, crooning with a sincerity that clearly wasn’t parody or caricature. Still, it was far too stylized to be mere mimicry. His band conjured a storm of dissonant non-keyboard electronics, angular rhythms, and Brian Eno’s futuristic treatments. Roxy Music embraced rather than mocked the early rock gestures of Elvis’s era. Ferry gave listeners permission to take Jerry Lee Lewis seriously, even reverently. Lewis was suddenly an avant-garde icon, pounding the keys with the same abandon that Eno applied to his electronics (witness Richard Trythall’s 1977 musique concrète: Omaggio a Jerry Lee Lewis).

That was the radicalism of early Roxy Music, which cannot be grasped retrospectively, even by the most avid young musicologist. Roxy dissolved the borders that the tribes of 1972 held sacred. They showed that ’50s rock, glam stylization, and avant-garde electronics could coexist in an unstable but persistent alloy. The shock of that is hard to grasp from today’s vantage point, when music is not tied to identity and “classic-rock” Roxy Music is remembered for Ferry’s Avalon-era suave crooning.

Oddly, and I think almost uniquely, as the band moved mainstream over the next fifteen years, the noisy, Eno-era chaos was retroactively smoothed into the same brand identity as Avalon. For later fans, there was no sharp rupture; the old chaos was domesticated and folded back into the same style sensibility.

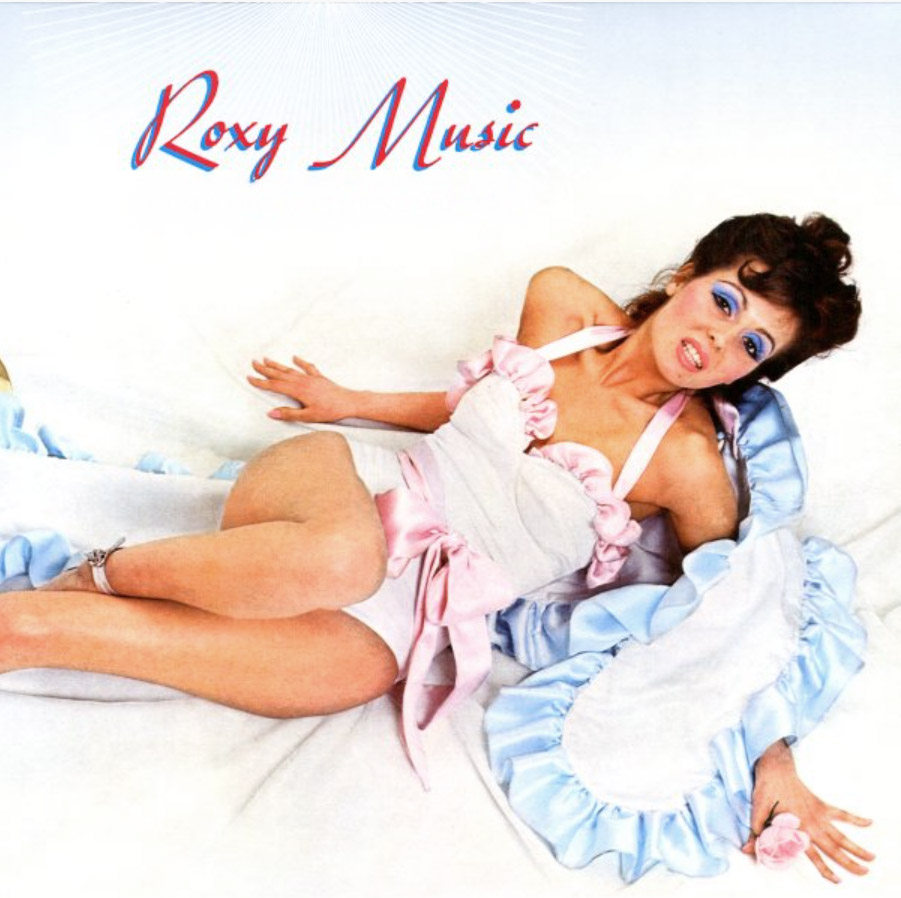

But the rupture had existed. Their cover art reinforced it. Roxy Music (1972) with Kari-Ann Muller posing like a mid-century pin-up, was tame in skin exposure compared to H.R. Giger’s biomechanical nudity on ELP’s Brain Salad Surgery. The boldness of Roxy Music’s cover lay in context, not ribaldry. The sleeve was bluntly terrestrial. For a prog listener used to studying a Roger Dean landscape on a first listen of a new Yes album, Roxy Music surely seemed an insult to seriousness.

When Fleetwood Mac reinvented themselves in 1975, new listeners treated it as rebirth. The Peter Green blues band that authored Black Magic Woman and the Buckingham–Nicks hit machine lived in separate mental compartments. Very few Rumours-era fans felt obliged to revisit Then Play On or Kiln House, and most who did saw them as curiosities. Similarly, Genesis underwent a hard split. Its listeners did not treat Foxtrot and Invisible Touch as facets of a single project.

Roxy Music’s retrospective smoothing is almost unique in rock. Their chaos was polished backward into elegance. The Velvet Underground went the other way. At first their noise was cultish, even disposable. But as the legend of Reed, Cale, and Nico grew, the past was recoded as prophecy. White Light/White Heat became the seed of punk. The Velvet Underground & Nico turned into the Bible of indie rock. Even Loaded – a deliberate grab for radio play, stripped of abrasion – was absorbed into the myth and remembered as avant-garde. It wasn’t. But the halo of the band’s legend bled forward and made every gesture look radical.

Roxy Music remains an oddity. The suave Avalon listener in 1982 could put on Virginia Plain without embarrassment and believe that those early tracks were nearby on a continuum. Ferry’s suave sound bled backward and redefined the chaos. He retroactively re-coded the Eno-era racket. The radical rupture was smoothed out beneath the gloss of brand identity.

That’s why early Roxy is so hard to hear as it was first heard. In 1972 it was unclassifiable, a collision of tribes and eras. To grasp it, you have to forget everything that came after. Imagine a listener whose vinyl shelf ended with The Yes Album, Aqualung, Tarkus, Ash Ra Tempel, Curved Air, Meddle, Nursery Cryme, and Led Zeppelin IV. Sha Na Na was a trashy novelty act recycling respected antiques – Dion and the Belmonts, Ritchie Valens, Danny and the Juniors. Disco, punk, new wave? They didn’t exist.

Now, in that silence, sit back and spin up Ladytron.

I’m Only Neurotic When – Engineering Edition

Posted by Bill Storage in Commentary, Engineering & Applied Physics on October 7, 2025

The USB Standard of Suffering

The USB standard was born in the mid-1990s from a consortium of Intel, Microsoft, IBM, DEC, NEC, Nortel, and Compaq. They formed the USB Implementers Forum to create a universal connector. The four pins for power and data were arranged asymmetrically to prevent reverse polarity damage. But the mighty consortium gave us no way to know which side was up.

The Nielsen Norman Group found that users waste ten seconds per insertion. Billions of plugs times thirty years. We could have paved Egypt with pyramids. I’m not neurotic. I just hate death by a thousand USB cuts.

The Dyson Principle

I admire good engineering. I also admire honesty in materials. So naturally, I can’t walk past a Dyson vacuum without gasping. The thing looks like it was styled by H. R. Giger after a head injury. Every surface is ribbed, scooped, or extruded as if someone bred Google Gemini with CAD software, provided the prompt “manifold mania,” and left it running overnight. Its transparent canister resembles an alien lung. There are ducts that lead nowhere, fins that cool nothing, and bright colors that imply importance. It’s all ornamental load path.

To what end? Twice the size and weight of a sensible vacuum, with eight times the polar moment of inertia. (You get the math – of course you do.) You can feel it fighting your every turn, not from friction, but from ego. Every attempt at steering carries the mass distribution of a helicopter rotor. I’m not cleaning a rug, I’m executing a ground test of a manic gyroscope.

Dyson claims it never loses suction. Fine, but I lose patience. It’s a machine designed for showroom admiration, not torque economy. Its real vacuum is philosophical: the absence of restraint. I’m not neurotic. I just believe a vacuum should obey the same physical laws as everything else in my house. I’m told design is where art meets engineering. That may be true, but in Dyson’s case, it’s also where geometry goes to die. There’s form, there’s function, and then there’s what happens when you hire a stylist who dreams in centrifugal-manifold Borg envy.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Physics

No one but Frank Lloyd Wright could have designed these cantilevered concrete roof supports, the tour guide at the Robie House intoned reverently, as though he were describing Moses with a T-square. True – and Mr. Wright couldn’t have either. The man drew poetry in concrete, but concrete does not care for poetry. It likes compression. It hates tension and bending. It’s like trying to make a violin out of breadsticks.

They say Wright’s genius was in making buildings that defied gravity. True in a sense – but only because later generations spent fifty times his budget figuring ways to install steel inside the concrete so gravity and the admirers of his genius wouldn’t notice. We have preserved his vision, yes, but only through subterfuge and eternal rebar vigilance.

Considered the “greatest American architect of all time” by people who can name but one architect, Wright made it culturally acceptable for architects to design expressive, intensely personal museums. The Guggenheim continues to thrill visitors with a unique forum for contemporary art. Until they need the bathroom – a feature more of an afterthought for Frank. Try closing the door in there without standing on the toilet. Paris hotels took a cue.

The Interface Formerly Known as Knob

Somewhere, deep in a design studio with too much brushed aluminum and not enough common sense, a committee decided that what drivers really needed was a touch screen for everything. Because nothing says safety like forcing the operator of a two-ton vehicle to navigate a software menu to adjust the defroster.

My car had a knob once. It stuck out. I could find it. I could turn it without looking. It was a miracle of tactile feedback and simple geometry. Then someone decided that physical controls were “clutter.” Now I have a 12-inch mirror that reflects my fingerprints and shame. To change the volume, I have to tap a glowing icon the size of an aspirin, located precisely where sunlight can erase it. The radio tuner is buried three screens deep, right beside the legal disclaimer that won’t go away until I hit Accept. Every time I start the thing. And the Bluetooth? It won’t connect while the car is moving, as if I might suddenly swerve off the road in a frenzy of unauthorized pairing. Design meets an army of failure-to-warn attorneys.

Human factors used to mean designing for humans. Now it means designing obstacles that test our compliance. I get neurotic when I recall a world where you could change the volume by touch instead of prayer.

Automation Anxiety

But the horror of car automation goes deeper, far beyond its entertainment center. The modern car no longer trusts me. I used to drive. Now I negotiate. Everything’s “smart” except the decisions. I rented one recently – some kind of half-electric pseudopod that smelled of despair and fresh software – and tried to execute a simple three-point turn on a dark mountain road. Halfway through, the dashboard blinked, the transmission clunked, and without warning the thing threw itself into Park and set the emergency brake.

I sat there in the dark, headlamps cutting into trees, wondering what invisible crime I’d committed. No warning lights, no chime, no message – just mutiny. When I pressed the accelerator, nothing. Had it died of fright? Then I remembered: modern problems require modern superstitions. I turned it off and back on again. Reboot – the digital age’s holy rite of exorcism. It worked.

Only later did I learn, through the owner’s manual’s runic footnotes, that the car had seen “an obstacle” in the rear camera and interpreted it as a cliff. In reality it was a clump of weeds. The AI mistook grass for death.

So now, in 2025, the same species that landed on the Moon has produced a vehicle that prevents a three-point turn for my own good. Not progress, merely the illusion of it – technology that promises safety by eliminating the user. I’m not neurotic. I just prefer my machines to ask before saving my life by freezing in place as headlights come around the bend.

The Illusion of Progress

There’s a reason I carry a torque wrench. It’s not to maintain preload. It’s to maintain standards. Torque is truth, expressed in foot-pounds. The world runs on it.

Somewhere along the way, design stopped being about function and started being about feelings. You can’t torque a feeling. You can only overdo it. Hence the rise of things that are technically advanced but spiritually stupid. Faucets that require a firmware update, refrigerators with Twitter accounts. Cars that disable half their features because you didn’t read the EULA while merging onto the interstate.

I’m told this is innovation. No, it’s entropy with a bottomless budget. After the collapse, I expect future archaeologists to find me in a fossilized Subaru, finger frozen an inch from the touchscreen that controlled the wipers.

Until then, I’ll keep my torque wrench, thank you. And I’ll keep muting TikTok’s #lifehacks tag, before another self-certified engineer shows me how to remove stripped screws with a banana. I’m not neurotic. I’ve learned to live with people who do it wrong.

art, criticism, engineering, humor, travel

4 Comments