Posts Tagged graph-computing

Unlocking the Secrets of Bulk Metallic Glass with Graph Computing

Posted by Bill Storage in Engineering & Applied Physics on June 24, 2025

This blog post was written in May 2022 by Amy Skowronski and Bill Storage for {Company}. {Company} did not accept it (or a shorter version) for publication because it was tangential to their current (at that time) focus. I’ll comment on that decision in a future post.

Fraud detection, drug discovery, and network security have all advanced with the help of graph computing – but these are just the early, obvious wins. The deeper promise of {Company}’s graph-native platform lies in uncovering complex relationships in domains most systems aren’t built to touch. To show what that looks like, we turn to a frontier yet revealing application: a class of advanced materials known as Bulk Metallic Glass.

Imagine a metal that’s stronger than steel, bends like plastic, and resists corrosion like glass. Bulk metallic glass (BMG), discovered in the 1960s, was found to have such characteristics. Recent advancements, enabled in part by high performance computing, give this revolutionary material the potential to transform industries from aerospace to medical devices.

Unlike the orderly atomic structures of common metals, BMGs boast a chaotic, amorphous arrangement that defies traditional metallurgy. At {Company}, we’re harnessing the power of graph computing to decode BMG’s atomic secrets, unlocking new possibilities for materials science. In this post, we’ll explore how BMGs differ from common metals and why graph analytics is the key to designing the next generation of advanced materials.

What Makes Bulk Metallic Glass So Special?

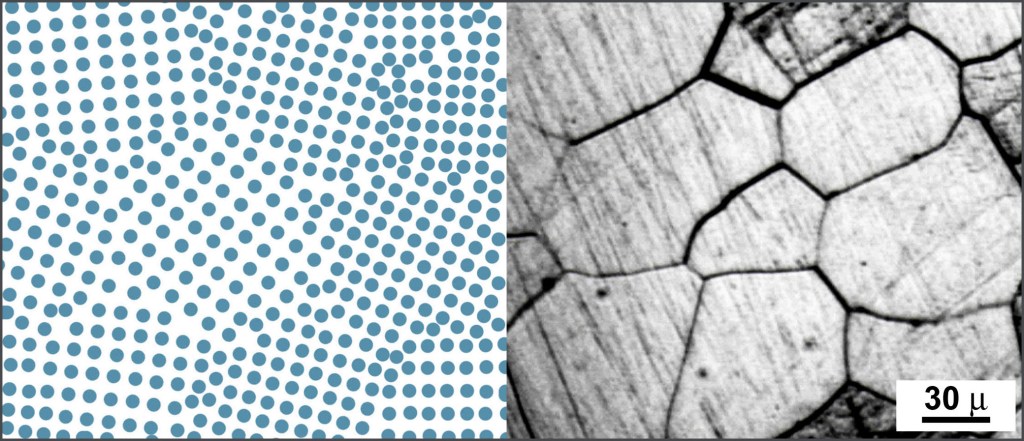

To understand BMGs, let’s start with the basics of metal structure. Most metals like steel and aluminum form crystalline lattices. These are highly organized, repeating patterns of atoms. The lattices define how metals behave: their strength, ductility, and even how they corrode. Common arrangements include:

- Face-Centered Cubic (FCC): Picture a cube with atoms at each corner and in the center of each face. This is most aluminum and copper. FCC metals are more ductile, ideal for shaping into wires or sheets.

- Body-Centered Cubic (BCC): Think of a cube with an atom at each corner and one in the center (e.g., iron at room temperature, which becomes FCC at higher temperatures). BCC metals are strong but less ductile, making them prone to brittle fracture under stress.

- Hexagon Close-Packed (HCP): Imagine tightly packed spheres stacked in a hexagonal pattern. This is most magnesium and titanium. HCP metals offer a balance of strength and formability, common in aerospace components.

All these structures are orderly, predictable, and rigid. But they have flaws – dislocations and grain boundaries where crystal regions meet. The boundaries act like seams, weaker than the surrounding fabric. Cracks and corrosion exploit the boundaries. Enter bulk metallic glass.

BMGs are amorphous; their atoms are arranged in a random, glass-like state, resembling a frozen liquid. Instead of lattices, BMG atoms are arranged in tightly packed clusters. This chaos gives BMGs unique properties:

- Incredible Strength: Without grain boundaries, BMGs resist cracking. Their strengths reach 2–3 GPa (300,000–400,000 psi), exceeding that of many high-strength steels, which typically top out around 1.5–2 GPa.

- Elasticity: BMGs can flex like polymers, deforming up to 2% before yielding, far exceeding the behavior of normal metals.

- Corrosion Resistance: Absence of ordered planes makes it harder for chemicals to attack and penetrate. BMGs are ideal for harsh environments like jet engines or implants.

- Processability: BMGs can be molded like glass when heated into their supercooled liquid region, enabling complex shapes for gears or biomedical stents.

Of course, there’s a catch, one that has hindered BMG development for decades. Designing BMGs is arduous. Their properties depend on precise compositions (e.g., Zr41.2Ti13.8Cu12.5Ni10Be22.5, known as Vitreloy 1) and extreme cooling rates in early systems (10⁵–10⁶ K/sec), though modern BMGs can form at rates as low as 1–100 K/sec. Understanding their atomic structure means solving a 3D puzzle with billions of pieces.

Graph Computing: Decoding BMG’s Atomic Chaos

BMGs’ amorphous structure is a network of atoms connected by bonds, with no repeating pattern. This makes them a perfect fit for graph analytics, where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges. {Company’s} high-performance graph platform can model these atomic networks at massive scale, revealing insights that traditional tools can’t touch. Here’s how it works:

1. Modeling the Amorphous Network

Imagine a BMG sample with billions of atoms, each bonded to 8–13 neighbors in a random cluster. {Company} represents this as a graph. Each node (atom) has properties like element type (e.g., Zr, Cu) and position. Each edge (bond) has attributes like bond strength or distance. Unlike crystalline metals, where lattices repeat predictably, BMG graphs are irregular, with varying degrees (number of bonds per atom) and clustering coefficients (how tightly atoms pack locally).

Using {Company’s} distributed graph engine, researchers can ingest terabytes of molecular dynamics (MD) simulation data – snapshots of atomic positions from supercomputers – and build these graphs in real time. Our platform’s ability to handle sparse, irregular graphs at scale (think 109 nodes and 1010 edges) makes it ideal for BMGs, outperforming traditional methods by 10–100x.

2. Analyzing Local Atomic Clusters

BMGs owe their strength to short-range order – local clusters like icosahedra (12 atoms around a central one) or tetrahedra (4 atoms tightly packed). These clusters don’t repeat globally but dominate locally, influencing properties like ductility. {Company’s} graph algorithms, like community detection (e.g., Louvain clustering), identify these motifs by finding densely connected subgraphs. For example, a high icosahedral cluster count in a Zr-based BMG correlates with better glass-forming ability and higher resistance to shear localization.

We also use graph neural networks (GNNs) to predict cluster stability. GNNs, using high-quality training data, learn from the graph’s topology and node features (e.g., atomic radii, electronegativity), predicting which compositions favor amorphous structures. This accelerates BMG design, reducing trial-and-error in the lab.

3. Simulating Defects and Dynamics

BMGs aren’t perfect. Shear transformation zones (STZs) – regions where atoms rearrange under stress – control their plasticity. {Company} models STZs as anomalous subgraphs, where nodes have unusual connectivity (e.g., lower or higher degree than average). Our anomaly detection algorithms can pinpoint these defects, helping engineers predict failure points.

Dynamic processes, like atomic rearrangements during cooling, are modeled as temporal graphs, where atom positions and inferred bonds change over time due to thermal motion or stress. {Company’s} real-time processing (powered by HPC roots) tracks these changes at scale, revealing how cooling rates affect amorphous stability. This is critical for scaling BMG production, because slow cooling often leads to unwanted crystallization.

4. Optimizing Composition

BMG recipes are complex, with 3–5 elements in precise ratios. {Company’s} graph traversal algorithms explore compositional spaces, identifying combinations that maximize icosahedral clusters or minimize crystallization risk. For instance, adding 1% Be to a Zr-Cu alloy can stabilize the amorphous phase. Our platform integrates with machine learning pipelines, enabling researchers to iterate faster than ever.

Why BMG Matters to Industry

BMGs are already making waves:

- Aerospace: NASA’s BMG gears for Mars rovers (developed and tested, not production to our knowledge) are 2x stronger than titanium, with no grain boundaries to fail under stress.

- Medical Devices: BMG implants resist corrosion in the body, lasting longer than the best stainless steels.

- Electronics: BMG casings for smartphones (e.g., Apple’s trials) combine strength with moldability for sleek designs.

The Future of Materials Science with {Company}

The global advanced materials market is projected to hit $1.1 trillion by 2027, and BMGs are a growing slice. But their potential is untapped due to design complexity. {Company’s} graph platform bridges this gap, enabling researchers to model, analyze, and optimize BMG structures at unprecedented scale. {Company’s} graph computing platform, with its roots in high-performance computing and expertise in Graph AI, is the perfect partner for this journey.

graph-computing, high-performance-computing, metallurgy, science

Recent Posts

- Anger As Argument – the Facebook Dividend

- Crystals Know What Day It Is

- Don’t Skimp on Shoes

- Dugga Dugga Dugga

- Robert Reich, Genius

- Bridging the Gap: Investor – Startup Psychology and What VCs Really Want to Hear

- Lawlessness Is a Choice, Bugliosi Style

- Fattening Frogs For Snakes

- Carving the Eagle

- It’s the Losers Who Write History

- Removable Climbing Bolt Stress Under Offset Loading

- Things to See in Palazzo Massimo

- Climbing Taiwan Removable Bolts Review

- The Arch of Constantine

- Deficient Discipleship in Environmental Science

- The End of Science Again

- Mark as Midrash

- Physics for Cold Cavers: NASA vs Hefty and Husky

- I’m Only Neurotic When – Engineering Edition

- I’m Only Neurotic When You Do It Wrong

- The Comet, the Clipboard, and the Knife

- Cave Bolts – 3/8″ or 8mm? – Or Wrong Question?

- Roxy Music and Forgotten Social Borders

- “He Tied His Lace” – Rum, Grenades and Bayesian Reasoning in Peaky Blinders

- Gospel of Mark: A Masterpiece Misunderstood, Part 7 – Mark Before Modernism

- Gospel of Mark, Masterpiece Misunderstood, Part 6 – Mark, Paul and James: The Silence, the Self and the Law

- The Gospel of Mark: A Masterpiece Misunderstood, Part 5 – Mark’s Interpreter Speaks

- The Gospel of Mark: A Masterpiece Misunderstood, Part 4 – Silence and Power

Archives

Recent Comments