Posts Tagged History of Art

The Arch of Constantine

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Art on October 31, 2025

This is for Mike and Andrea, on their first visit to Rome.

Some people take up gardening. I dug into the Arch of Constantine. Deep. I’ll admit it, I got a little obsessed. What started as a quick look turned into a full dig through the dust of Roman politics as seen by art historians and classicists, writers with a gift for making the obvious sound profound and the profound impenetrable. Think of a collaboration between poets, lawyers, and a Latin thesaurus. One question led to another, and before I knew it, I was knee-deep in relief panels, inscriptions, and bitter academic feuds from 1903. If this teaser does anything for you, order a pizza and head over to my long version, revised today to incorporate recent scholarship, which is making great strides.

The Arch of Constantine stands just beside the Colosseum, massive and pale against the traffic. It was dedicated in 315 CE to celebrate Emperor Constantine’s victory over his rival Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge. On paper it’s a “triumphal arch,” but that’s not quite true. Constantine never held a formal triumph, and the monument itself was assembled partly from spare parts of older imperial projects.

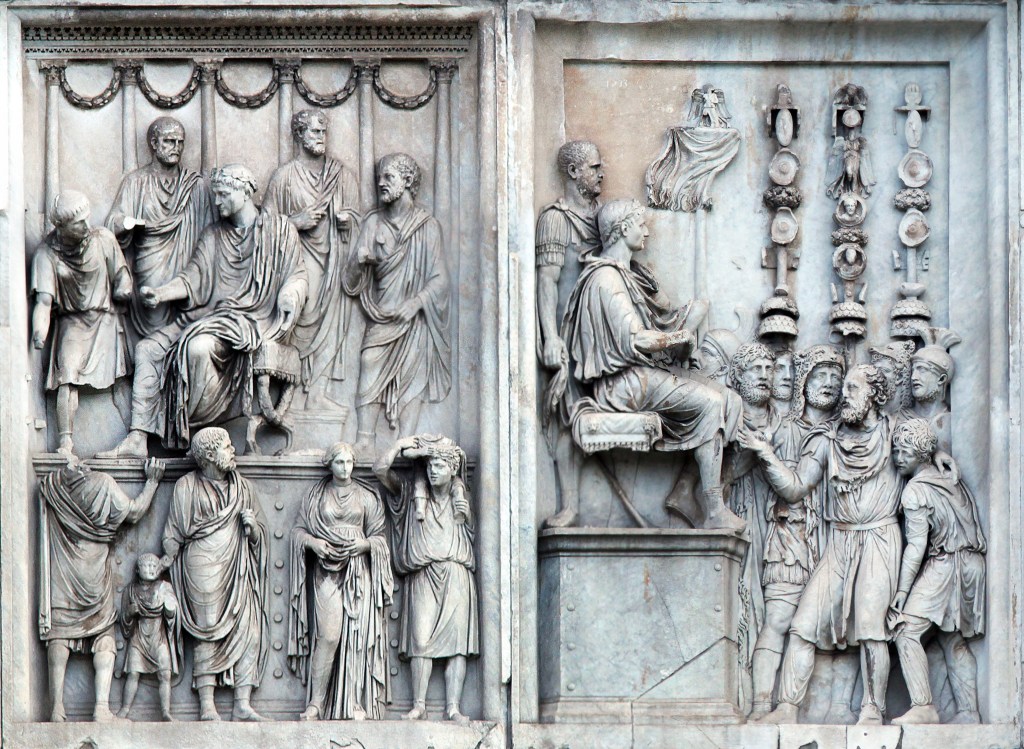

Most of what you see wasn’t made for Constantine at all. His builders raided earlier monuments – especially from the reigns of Hadrian, Trajan, and Marcus Aurelius – and grafted those sculptures onto the new structure. Look closely and you can still spot the mismatches. The heads have been recut. A scene that once showed Emperor Hadrian hunting a lion now shows Constantine doing the honors, with a few clumsy adjustments to the drapery. Other panels, taken from Marcus Aurelius’s monuments, show the emperor addressing troops or granting clemency, only now it’s Constantine’s face and Constantine’s name.

These borrowed panels aren’t just decoration. They were carefully chosen to tie Constantine to the “good emperors” of the past, especially Marcus Aurelius, the philosopher-king. By mixing their images with his own, Constantine claimed continuity with Rome’s golden age while quietly erasing the messy years between.

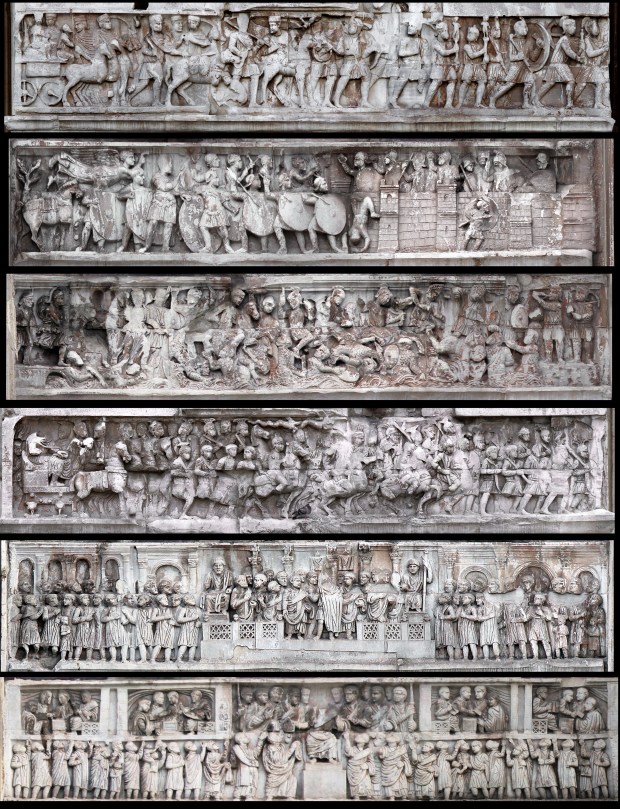

The long strip of carving that wraps around the lower part of the arch is the one section made entirely for Constantine’s time. It’s a running narrative of his civil war against Maxentius. Starting on the west side, you can see Constantine setting out from Milan, soldiers marching behind his chariot. Around the corner, he besieges a walled city – probably Verona – and towers over his men, twice their size, a new kind of emperor who commands by sheer presence. The next panel shows the chaotic battle at the Milvian Bridge, where Maxentius’s troops drown in the Tiber while Constantine’s army presses forward. The story ends with Constantine entering Rome and addressing the citizens from a raised platform, a ruler both human and divine.

The figures look stiff and simplified compared to the older reliefs above them, but that’s part of the shift the arch represents. Art was moving away from naturalism toward symbolism. Constantine isn’t shown as an individual man but as an idea: the chosen ruler, the earthly image of divine authority.

That message runs through the inscription carved across the top. It declares that Constantine won instinctu divinitatis – “by divine inspiration.” The phrase is unique; no one had used it before. It’s deliberately vague, as if leaving room for different gods to take the credit. For pagans, it could mean Apollo or Sol Invictus. For Christians, it sounded like the hand of the one God. Either way, it announced a new kind of emperor, one who ruled not just with the favor of the gods but through them.

The Arch of Constantine isn’t simply a monument to a battle. It’s a scrapbook of Rome’s artistic past and a statement of political legitimacy. Read carefully, it is an early sign that the empire was in for religion, hard times, and down-sizing.

Photos and text copyright 2025 by William K Storage

Recent Comments