Posts Tagged news

Covid Response – Case Counts and Failures of Statistical Reasoning

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science on May 19, 2025

In my previous post I defended three claims made in an earlier post about relative successes in statistics and statistical reasoning in the American Covid-19 response. This post gives support for three claims regarding misuse of statistics and poor statistical reasoning during the pandemic.

Misinterpretation of Test Results (4)

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, many clinicians and media figures misunderstood diagnostic test accuracy, misreading PCR and antigen test results by overlooking pre-test probability. This caused false reassurance or unwarranted alarm, though some experts mitigated errors with Bayesian reasoning. This was precisely the type of mistake highlighted in the Harvard study decades earlier. (4)

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests, while considered the gold standard for detecting SARS-CoV-2, were known to have variable sensitivity (70–90%) depending on factors like sample quality, timing of testing relative to infection, and viral load. False negatives were a significant concern, particularly when clinicians or media interpreted a negative result as definitively ruling out infection without considering pre-test probability (the likelihood of disease based on symptoms, exposure, or prevalence). Similarly, antigen tests, which are less sensitive than PCR, were prone to false negatives, especially in low-prevalence settings or early/late stages of infection.

A 2020 article in Journal of General Internal Medicine noted that physicians often placed undue confidence in test results, minimizing clinical reasoning (e.g., pre-test probability) and deferring to imperfect tests. This was particularly problematic for PCR false negatives, which could lead to a false sense of security about infectivity.

A 2020 Nature Reviews Microbiology article reported that during the early pandemic, the rapid development of diagnostic tests led to implementation challenges, including misinterpretation of results due to insufficient consideration of pre-test probability. This was compounded by the lack of clinical validation for many tests at the time.

Media reports often oversimplified test results, presenting PCR or antigen tests as definitive without discussing limitations like sensitivity, specificity, or the role of pre-test probability. Even medical professionals struggled with Bayesian reasoning, leading to public confusion about test reliability.

Antigen tests, such as lateral flow tests, were less sensitive than PCR (pooled sensitivity of 64.2% in pediatric populations) but highly specific (99.1%). Their performance varied significantly with pre-test probability, yet early in the pandemic, they were sometimes used inappropriately in low-prevalence settings, leading to misinterpretations. In low-prevalence settings (e.g., 1% disease prevalence), a positive antigen test with 99% specificity and 64% sensitivity could have a high false-positive rate, but media and some clinicians often reported positives as conclusive without contextualizing prevalence. Conversely, negative antigen tests were sometimes taken as proof of non-infectivity, despite high false-negative rates in early infection.

False negatives in PCR tests were a significant issue, particularly when testing was done too early or late in the infection cycle. A 2020 study in Annals of Internal Medicine found that the false-negative rate of PCR tests varied by time since exposure, peaking at 20–67% depending on the day of testing. Clinicians who relied solely on a negative PCR result without considering symptoms or exposure history often reassured patients they were not infected, potentially allowing transmission.

In low-prevalence settings, even highly specific tests like PCR (specificity ~99%) could produce false positives, especially with high cycle threshold (Ct) values indicating low viral loads. A 2020 study in Clinical Infectious Diseases found that only 15.6% of positive PCR results in low pre-test probability groups (e.g., asymptomatic screening) were confirmed by an alternate assay, suggesting a high false-positive rate. Media amplification of positive cases without context fueled public alarm, particularly during mass testing campaigns.

Antigen tests, while rapid, had lower sensitivity and were prone to false positives in low-prevalence settings. An oddly credible 2021 Guardian article noted that at a prevalence of 0.3% (1 in 340), a lateral flow test with 99.9% specificity could still yield a 5% false-positive rate among positives, causing unnecessary isolation or panic. In early 2020, widespread testing of asymptomatic individuals in low-prevalence areas led to false positives being reported as “new cases,” inflating perceived risk.

Many Covid professionals mitigated errors with Bayesian reasoning, using pre-test probability, test sensitivity, and specificity to calculate the post-test probability of disease. Experts who applied this approach were better equipped to interpret COVID-19 test results accurately, avoiding over-reliance on binary positive/negative outcomes.

Robert Wachter, MD, in a 2020 Medium article, explained Bayesian reasoning for COVID-19 testing, stressing that test results must be interpreted with pre-test probability. For example, a negative PCR in a patient with a 30% pre-test probability (based on symptoms and prevalence) still carried a significant risk of infection, guiding better clinical decisions. In Germany, mathematical models incorporating pre-test probability optimized PCR allocation, ensuring testing was targeted to high-risk groups.

Cases vs. Deaths (5)

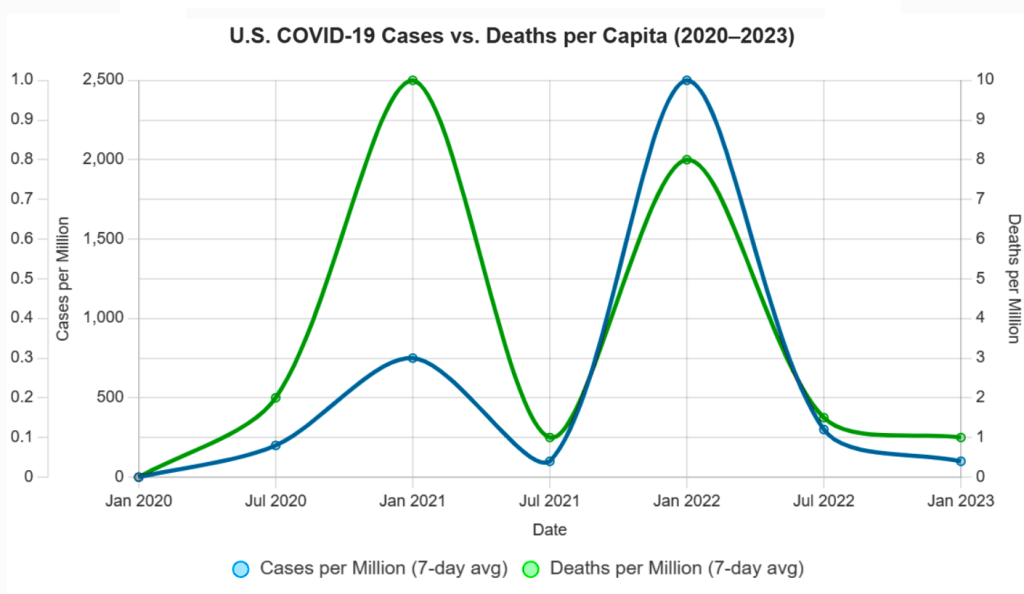

One of the most persistent statistical missteps during the pandemic was the policy focus on case counts, devoid of context. Case numbers ballooned or dipped not only due to viral spread but due to shifts in testing volume, availability, and policies. Covid deaths per capita rather than case count would have served as a more stable measure of public health impact. Infection fatality rates would have been better still.

There was a persistent policy emphasis on cases alone. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, public health policies, such as lockdowns, mask mandates, and school closures, were often justified by rising case counts reported by agencies like the CDC, WHO, and national health departments. For example, in March 2020, the WHO’s situation reports emphasized confirmed cases as a primary metric, influencing global policy responses. In the U.S., states like California and New York tied reopening plans to case thresholds (e.g., California’s Blueprint for a Safer Economy, August 2020), prioritizing case numbers over other metrics. Over-reliance on case-based metrics was documented by Trisha Greenhalgh in Lancet (Ten scientific reasons in support of airborne transmission…).

Case counts, without context, were frequently reported without contextualizing factors like testing rates or demographics, leading to misinterpretations. A 2021 BMJ article criticized the overreliance on case counts, noting they were used to “justify public health measures” despite their variability, supporting the claim of a statistical misstep. Media headlines, such as “U.S. Surpasses 100,000 Daily Cases” (CNN, November 4, 2020), amplified case counts, often without clarifying testing changes, fostering fear-driven policy decisions.

Case counts were directly tied to testing volume, which varied widely. In the U.S., testing increased from ~100,000 daily tests in April 2020 to over 2 million by November 2020 (CDC data). Surges in cases often coincided with testing ramps, e.g., the U.S. case peak in July 2020 followed expanded testing in Florida and Texas. Testing access was biased (in the statistical sense). Widespread testing including asymptomatic screening inflated counts. Policies like mandatory testing for hospital admissions or travel (e.g., New York’s travel testing mandate, November 2020) further skewed numbers. 2020 Nature study highlighted that case counts were “heavily influenced by testing capacity,” with countries like South Korea detecting more cases due to aggressive testing, not necessarily higher spread. This supports the claim that testing volume drove case fluctuations beyond viral spread (J Peto, Nature – 2020).

Early in the pandemic, testing was limited due to supply chain issues and regulatory delays. For example, in March 2020, the U.S. conducted fewer than 10,000 tests daily due to shortages of reagents and swabs, underreporting cases (Johns Hopkins data). This artificially suppressed case counts. A 2021 Lancet article (R Horton) noted that “changes in testing availability distorted case trends,” with low availability early on masking true spread and later increases detecting more asymptomatic cases, aligning with the claim.

Testing policies, such as screening asymptomatic populations or requiring tests for specific activities, directly impacted case counts. For example, in China, mass testing of entire cities like Wuhan in May 2020 identified thousands of cases, many asymptomatic, inflating counts. In contrast, restrictive policies early on (e.g., U.S. CDC’s initial criteria limiting tests to symptomatic travelers, February 2020) suppressed case detection.

In the U.S., college campuses implementing mandatory weekly testing in fall 2020 reported case spikes, often driven by asymptomatic positives (e.g., University of Wisconsin’s 3,000+ cases, September 2020). A 2020 Science study (Assessment of SARS-CoV-2 screening) emphasized that “testing policy changes, such as expanded screening, directly alter reported case numbers,” supporting the claim that policy shifts drove case variability.

Deaths per capita, calculated as total Covid-19 deaths divided by population, are less sensitive to testing variations than case counts. For example, Sweden’s deaths per capita (1,437 per million by December 2020, Our World in Data) provided a clearer picture of impact than its case counts, which fluctuated with testing policies. Belgium and the U.K. used deaths per capita to compare regional impacts, guiding resource allocation. A 2021 JAMA study argued deaths per capita were a “more reliable indicator” of pandemic severity, as they reflected severe outcomes less influenced by testing artifacts. Death reporting had gross inconsistencies (e.g., defining “Covid-19 death”), but it was more standardized than case detection.

Infection Fatality Rates (IFR) reports the proportion of infections resulting in death, making it less prone to testing biases. A 2020 Bulletin of the WHO meta-analysis estimated a global IFR of ~0.6% (range 0.3-1.0%), varying by age and region. IFR gave a truer measure of lethality. Seroprevalence studies in New York City (April 2020) estimated an IFR of ~0.7%, offering insight into true mortality risk compared to case fatality rates (CFR), which were inflated by low testing (e.g., CFR ~6% in the U.S., March 2020).

Shifting Guidelines and Aerosol Transmission (6)

The “6-foot rule” was based on outdated models of droplet transmission. When evidence of aerosol spread emerged, guidance failed to adapt. Critics pointed out the statistical conservatism in risk modeling, its impact on mental health and the economy. Institutional inertia and politics prevented vital course corrections.

The 6-foot (or 2-meter) social distancing guideline, widely adopted by the CDC and WHO in early 2020, stemmed from historical models of respiratory disease transmission, particularly the 1930s work of William F. Wells on tuberculosis. Wells’ droplet model posited that large respiratory droplets fall within 1–2 meters, implying that maintaining this distance reduces transmission risk. The CDC’s March 2020 guidance explicitly recommended “at least 6 feet” based on this model, assuming most SARS-CoV-2 transmission occurred via droplets.

The droplet model was developed before modern understanding of aerosol dynamics. It assumed that only large droplets (>100 μm) were significant, ignoring smaller aerosols (<5–10 μm) that can travel farther and remain airborne longer. A 2020 Nature article noted that the 6-foot rule was rooted in “decades-old assumptions” about droplet size, which did not account for SARS-CoV-2’s aerosol properties, such as its ability to spread in poorly ventilated spaces beyond 6 feet.

Studies, like a 2020 Lancet article by Morawska and Milton, argued that the 6-foot rule was inadequate for aerosolized viruses, as aerosols could travel tens of meters in certain conditions (e.g., indoor settings with low air exchange). Real-world examples, such as choir outbreaks (e.g., Skagit Valley, March 2020, where 53 of 61 singers were infected despite spacing), highlighted transmission beyond 6 feet, undermining the droplet-only model.

The WHO initially downplayed aerosol transmission, stating in March 2020 that COVID-19 was “not airborne” except in specific medical procedures (e.g., intubation). After the July 2020 letter, the WHO updated its guidance on July 9, 2020, to acknowledge “emerging evidence” of airborne spread but maintained droplet-focused measures (e.g., 1-meter distancing) without emphasizing ventilation or masks for aerosols. A 2021 BMJ article criticized the WHO for “slow and risk-averse” updates, noting that full acknowledgment of aerosol spread was delayed until May 2021.

The CDC also failed to update its guidance. In May 2020, it emphasized droplet transmission and 6-foot distancing. A brief September 2020 update mentioning “small particles” was retracted days later, reportedly due to internal disagreement. The CDC fully updated its guidance to include aerosol transmission in May 2021, recommending improved ventilation, but retained the 6-foot rule in many contexts (e.g., schools) until 2022. Despite aerosol evidence, the 6-foot rule remained a cornerstone of policies. For example, U.S. schools enforced 6-foot desk spacing in 2020–2021, delaying reopenings despite studies (e.g., a 2021 Clinical Infectious Diseases study).

Early CDC and WHO models overestimated droplet transmission risks while underestimating aerosol spread, leading to rigid distancing rules. A 2021 PNAS article by Prather et al. criticized these models as “overly conservative,” noting they ignored aerosol physics and real-world data showing low outdoor transmission risks. Risk models overemphasized close-contact droplet spread, neglecting long-range aerosol risks in indoor settings. John Ioannidis, in a 2020 European Journal of Clinical Investigation commentary, criticized the “precautionary principle” in modeling, which prioritized avoiding any risk over data-driven adjustments, leading to policies like prolonged school closures based on conservative assumptions about transmission.

Risk models rarely incorporated Bayesian updates with new data, specifically low transmission in well-ventilated spaces. A 2020 Nature commentary by Tang et al. noted that models failed to adjust for aerosol decay rates or ventilation, overestimating risks in outdoor settings while underestimating them indoors.

Researchers and public figures criticized prolonged social distancing and lockdowns, driven by conservative risk models, for exacerbating mental health issues. A 2021 The Lancet Psychiatry study reported a 25% global increase in anxiety and depression in 2020, attributing it to isolation from distancing measures. Jay Bhattacharya, co-author of the Great Barrington Declaration, argued in 2020 that rigid distancing rules, like the 6-foot mandate, contributed to social isolation without proportional benefits.

Tragically, A 2021 JAMA Pediatrics study concluded that Covid school closures increased adolescent suicide ideation by 12–15%. Economists and policy analysts, such as those at the American Institute for Economic Research (AIER), criticized the economic fallout of distancing policies. The 6-foot rule led to capacity restrictions in businesses (e.g., restaurants, retail), contributing to economic losses. A 2020 Nature Human Behaviour study estimated a 13% global GDP decline in Q2 2020 due to lockdowns and distancing measures.

Institutional inertia and political agendas prevented course corrections, such as prioritizing ventilation over rigid distancing. The WHO’s delay in acknowledging aerosols was attributed to political sensitivities. A 2020 Nature article (Lewis) reported that WHO advisors faced pressure to align with member states’ policies, slowing updates.

Next post, I’ll offer commentary on Covid policy from the perspective of a historian of science.

NPR: Free Speech and Free Money

Posted by Bill Storage in Commentary on May 6, 2025

The First Amendment, now with tote bags – because nothing says “free speech” like being subsidized.

Katherine Maher’s NPR press release begins: “NPR is unwavering in our commitment to integrity, editorial independence, and our mission to serve the American people in partnership with our NPR Member organizations. … We will vigorously defend our right to provide essential news, information and life-saving services to the American public.” (emphasis mine)

Maher’s claim that NPR will “defend our right to provide essential news, information, and life-saving services” is an exercise in rhetorical inflation. The word “right” carries weight in American political language – usually evoking constitutional protections like freedom of speech. But no clause in the First Amendment guarantees funding for journalism. The right to speak is not the right to be subsidized.

By framing NPR’s mission as a right, Maher conflates two distinct ideas: the freedom to broadcast without interference, and the claim to a public subsidy. One is protected by law; the other is a policy preference. To treat them as interchangeable is misleading. Her argument depends not on logic but on sentiment, presenting public funding as a moral obligation rather than a choice made by legislators.

Maher insists federal funding is a tiny slice of the budget – less than 0.0001% – and that each federal dollar attracts seven more from local sources. If true, this suggests NPR’s business model is robust. So why the alarm over defunding? The implication is that without taxpayer support, NPR’s “life-saving services” will vanish. But she never specifies what those services are. Emergency broadcasts? Election coverage? The phrase is vague enough to imply much while committing to nothing.

The real issue Maher avoids is whether the federal government should be funding media at all. Private outlets, large and small, manage to survive without help from Washington. They exercise their First Amendment rights freely, supported by subscriptions, ads, or donations. NPR could do the same – especially since its audience is wealthier and more educated than average. If its listeners value it, they can pay for it.

Instead of making that case, Maher reaches for historical authority. She invokes the Founding Fathers and the 1967 Public Broadcasting Act. But the founders, whatever their views on an informed citizenry, did not propose a state-funded media outlet. The Public Broadcasting Act was designed to ensure editorial independence – not guarantee permanent federal funding. Appealing to these sources lends NPR an air of legitimacy it should not need, and cannot claim in this context.

Then there’s the matter of bias. Maher praises NPR’s “high standards” and “factual reporting,” yet sidesteps the widespread perception that NPR leans left. Dismissing that concern doesn’t neutralize it – it feeds it. Public skepticism about NPR’s neutrality is a driving force behind calls for defunding. By ignoring this, Maher doesn’t just miss the opposition’s argument – she reinforces it, confirming the perception of bias by acting as if no other viewpoint is worth hearing.

In the end, Maher’s defense is a polished example of misdirection. Equating liberty with a line item is an argument that flatters the overeducated while fooling no one else. She presents a budgetary dispute as a constitutional crisis. She wraps policy preferences in the language of principle. And she evades the real question: if NPR is as essential and efficient as she claims, why can’t it stand on its own?

It is not an attack on the First Amendment to question public funding for NPR. It is a question of priorities. Maher had an opportunity to defend NPR on the merits. Instead, she reached for abstractions, hoping the rhetoric would do the work of reason. It doesn’t.

First Amendment, Free speech, Katherine Maher, Media bias, Media Criticism, news, NPR, pbs, Political Rhetoric, politics, Public Broadcasting, Taxpayer Funding, trump

4 Comments