Posts Tagged prog-rock

Roxy Music and Forgotten Social Borders

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Art on August 20, 2025

In the early 1970s rock culture was diverse, clannish and fiercely territorial. Musical taste usually carried with it an entire identity, including hair length and style, clothing – including shoes/boots – politics, and which record stores you could haunt. King Crimson, Yes, Pink Floyd, and Emerson, Lake & Palmer belonged to the progressive end of the spectrum.

By the early 1970s, progressive rock (prog, as shorthand began to appear in music press) was musical descriptor and social signal. Calling a band “progressive” implied a certain seriousness, technical sophistication, and intellectual ambition. It marked a listener as someone who prized virtuosity, complexity, and concept albums over pop singles. The label carried subtle class and educational connotations: prog fans were expected to appreciate classical references, odd time signatures, extended solos, and experimental studio techniques. King Crimson was often called avant-garde rock, though Henry Cow deserved the label much more. ELP was called symphonic rock, Pink Floyd was psychedelic rock, and Yes was Epic rock – but they were all prog. And listening to all this stuff made you smart. Or pretentious.

Across the divide, the early 70s saw greaser rock and the emerging ’50s nostalgia circuit. Sha Na Na, the sock-hop revival, the idea that a gold lamé suit was a passport to a simpler age ushered in the Happy Days craze and its music. Few people straddled those camps. A Crimson devotee wouldn’t admit to liking Sha Na Na if he wanted to keep his dignity. Rock music was attitude, self-image, and worldview.

Into that landscape stepped Roxy Music in 1972, and they were utterly bewildering. Bryan Ferry came dressed like a lounge lizard from a time-warped jukebox, crooning with a sincerity that clearly wasn’t parody or caricature. Still, it was far too stylized to be mere mimicry. His band conjured a storm of dissonant non-keyboard electronics, angular rhythms, and Brian Eno’s futuristic treatments. Roxy Music embraced rather than mocked the early rock gestures of Elvis’s era. Ferry gave listeners permission to take Jerry Lee Lewis seriously, even reverently. Lewis was suddenly an avant-garde icon, pounding the keys with the same abandon that Eno applied to his electronics (witness Richard Trythall’s 1977 musique concrète: Omaggio a Jerry Lee Lewis).

That was the radicalism of early Roxy Music, which cannot be grasped retrospectively, even by the most avid young musicologist. Roxy dissolved the borders that the tribes of 1972 held sacred. They showed that ’50s rock, glam stylization, and avant-garde electronics could coexist in an unstable but persistent alloy. The shock of that is hard to grasp from today’s vantage point, when music is not tied to identity and “classic-rock” Roxy Music is remembered for Ferry’s Avalon-era suave crooning.

Oddly, and I think almost uniquely, as the band moved mainstream over the next fifteen years, the noisy, Eno-era chaos was retroactively smoothed into the same brand identity as Avalon. For later fans, there was no sharp rupture; the old chaos was domesticated and folded back into the same style sensibility.

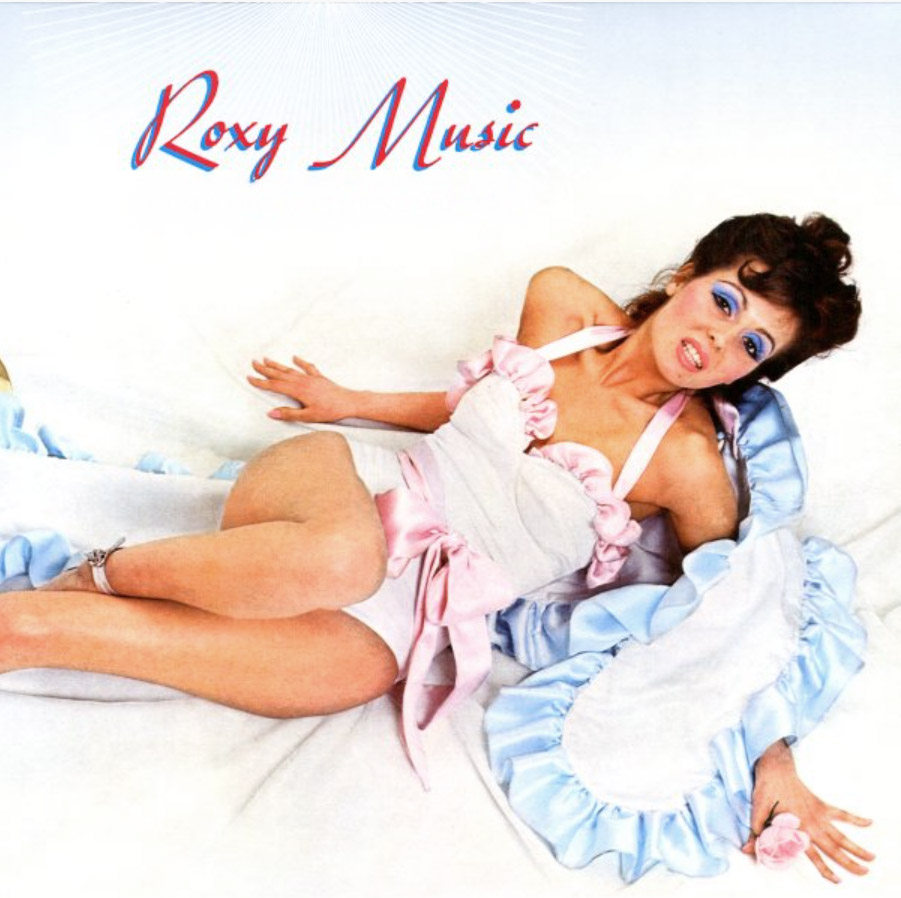

But the rupture had existed. Their cover art reinforced it. Roxy Music (1972) with Kari-Ann Muller posing like a mid-century pin-up, was tame in skin exposure compared to H.R. Giger’s biomechanical nudity on ELP’s Brain Salad Surgery. The boldness of Roxy Music’s cover lay in context, not ribaldry. The sleeve was bluntly terrestrial. For a prog listener used to studying a Roger Dean landscape on a first listen of a new Yes album, Roxy Music surely seemed an insult to seriousness.

When Fleetwood Mac reinvented themselves in 1975, new listeners treated it as rebirth. The Peter Green blues band that authored Black Magic Woman and the Buckingham–Nicks hit machine lived in separate mental compartments. Very few Rumours-era fans felt obliged to revisit Then Play On or Kiln House, and most who did saw them as curiosities. Similarly, Genesis underwent a hard split. Its listeners did not treat Foxtrot and Invisible Touch as facets of a single project.

Roxy Music’s retrospective smoothing is almost unique in rock. Their chaos was polished backward into elegance. The Velvet Underground went the other way. At first their noise was cultish, even disposable. But as the legend of Reed, Cale, and Nico grew, the past was recoded as prophecy. White Light/White Heat became the seed of punk. The Velvet Underground & Nico turned into the Bible of indie rock. Even Loaded – a deliberate grab for radio play, stripped of abrasion – was absorbed into the myth and remembered as avant-garde. It wasn’t. But the halo of the band’s legend bled forward and made every gesture look radical.

Roxy Music remains an oddity. The suave Avalon listener in 1982 could put on Virginia Plain without embarrassment and believe that those early tracks were nearby on a continuum. Ferry’s suave sound bled backward and redefined the chaos. He retroactively re-coded the Eno-era racket. The radical rupture was smoothed out beneath the gloss of brand identity.

That’s why early Roxy is so hard to hear as it was first heard. In 1972 it was unclassifiable, a collision of tribes and eras. To grasp it, you have to forget everything that came after. Imagine a listener whose vinyl shelf ended with The Yes Album, Aqualung, Tarkus, Ash Ra Tempel, Curved Air, Meddle, Nursery Cryme, and Led Zeppelin IV. Sha Na Na was a trashy novelty act recycling respected antiques – Dion and the Belmonts, Ritchie Valens, Danny and the Juniors. Disco, punk, new wave? They didn’t exist.

Now, in that silence, sit back and spin up Ladytron.

Recent Comments