Posts Tagged roman-empire

From Aqueducts to Algorithms: The Cost of Consensus

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science on July 9, 2025

The Scientific Revolution, we’re taught, began in the 17th century – a European eruption of testable theories, mathematical modeling, and empirical inquiry from Copernicus to Newton. Newton was the first scientist, or rather, the last magician, many historians say. That period undeniably transformed our understanding of nature.

Historians increasingly question whether a discrete “scientific revolution” ever happened. Floris Cohen called the label a straightjacket. It’s too simplistic to explain why modern science, defined as the pursuit of predictive, testable knowledge by way of theory and observation, emerged when and where it did. The search for “why then?” leads to Protestantism, capitalism, printing, discovered Greek texts, scholasticism, even weather. That’s mostly just post hoc theorizing.

Still, science clearly gained unprecedented momentum in early modern Europe. Why there? Why then? Good questions, but what I wonder, is why not earlier – even much earlier.

Europe had intellectual fireworks throughout the medieval period. In 1320, Jean Buridan nearly articulated inertia. His anticipation of Newton is uncanny, three centuries earlier:

“When a mover sets a body in motion he implants into it a certain impetus, that is, a certain force enabling a body to move in the direction in which the mover starts it, be it upwards, downwards, sidewards, or in a circle. The implanted impetus increases in the same ratio as the velocity. It is because of this impetus that a stone moves on after the thrower has ceased moving it. But because of the resistance of the air (and also because of the gravity of the stone) … the impetus will weaken all the time. Therefore the motion of the stone will be gradually slower, and finally the impetus is so diminished or destroyed that the gravity of the stone prevails and moves the stone towards its natural place.”

Robert Grosseteste, in 1220, proposed the experiment-theory iteration loop. In his commentary on Aristotle’s Posterior Analytics, he describes what he calls “resolution and composition”, a method of reasoning that moves from particulars to universals, then from universals back to particulars to make predictions. Crucially, he emphasizes that both phases require experimental verification.

In 1360, Nicole Oresme gave explicit medieval support for a rotating Earth:

“One cannot by any experience whatsoever demonstrate that the heavens … are moved with a diurnal motion… One can not see that truly it is the sky that is moving, since all movement is relative.”

He went on to say that the air moves with the Earth, so no wind results. He challenged astrologers:

“The heavens do not act on the intellect or will… which are superior to corporeal things and not subject to them.”

Even if one granted some influence of the stars on matter, Oresme wrote, their effects would be drowned out by terrestrial causes.

These were dead ends, it seems. Some blame the Black Death, but the plague left surprisingly few marks in the intellectual record. Despite mass mortality, history shows politics, war, and religion marching on. What waned was interest in reviving ancient learning. The cultural machinery required to keep the momentum going stalled. Critical, collaborative, self-correcting inquiry didn’t catch on.

A similar “almost” occurred in the Islamic world between the 10th and 16th centuries. Ali al-Qushji and al-Birjandi developed sophisticated models of planetary motion and even toyed with Earth’s rotation. A layperson would struggle to distinguish some of al-Birjandi’s thought experiments from Galileo’s. But despite a wealth of brilliant scholars, there were few institutions equipped or allowed to convert knowledge into power. The idea that observation could disprove theory or override inherited wisdom was socially and theologically unacceptable. That brings us to a less obvious candidate – ancient Rome.

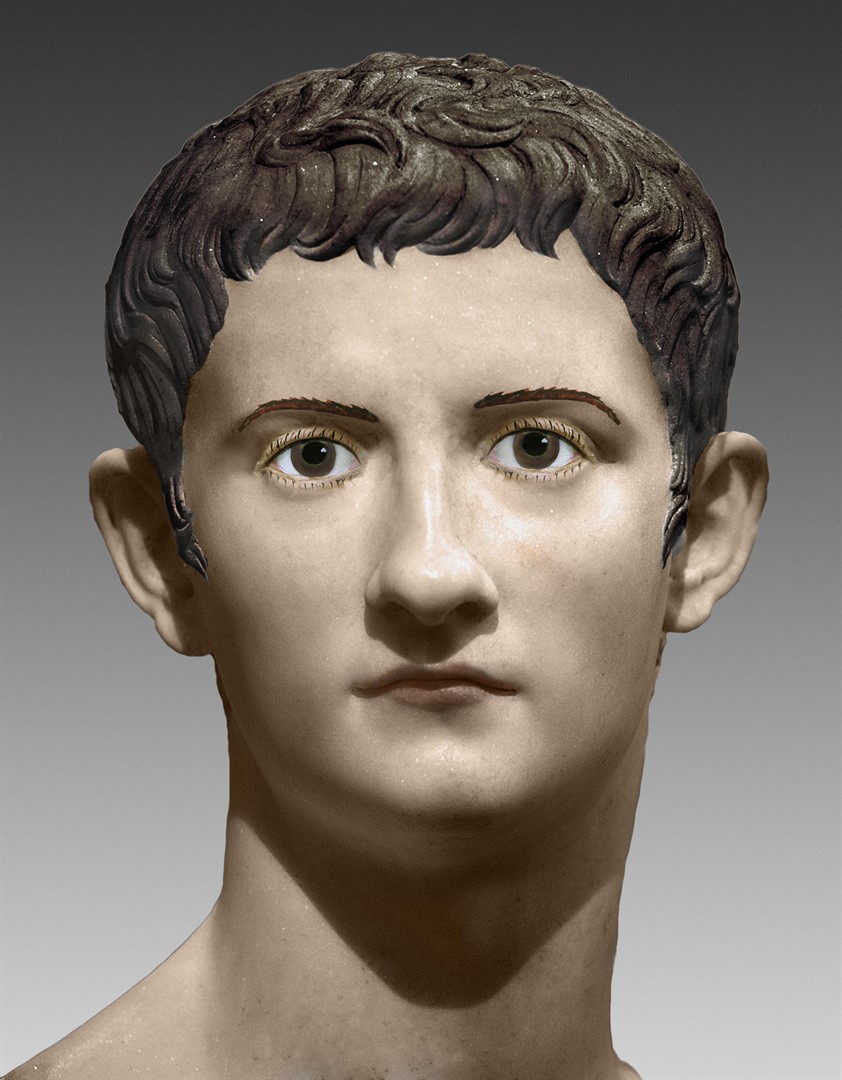

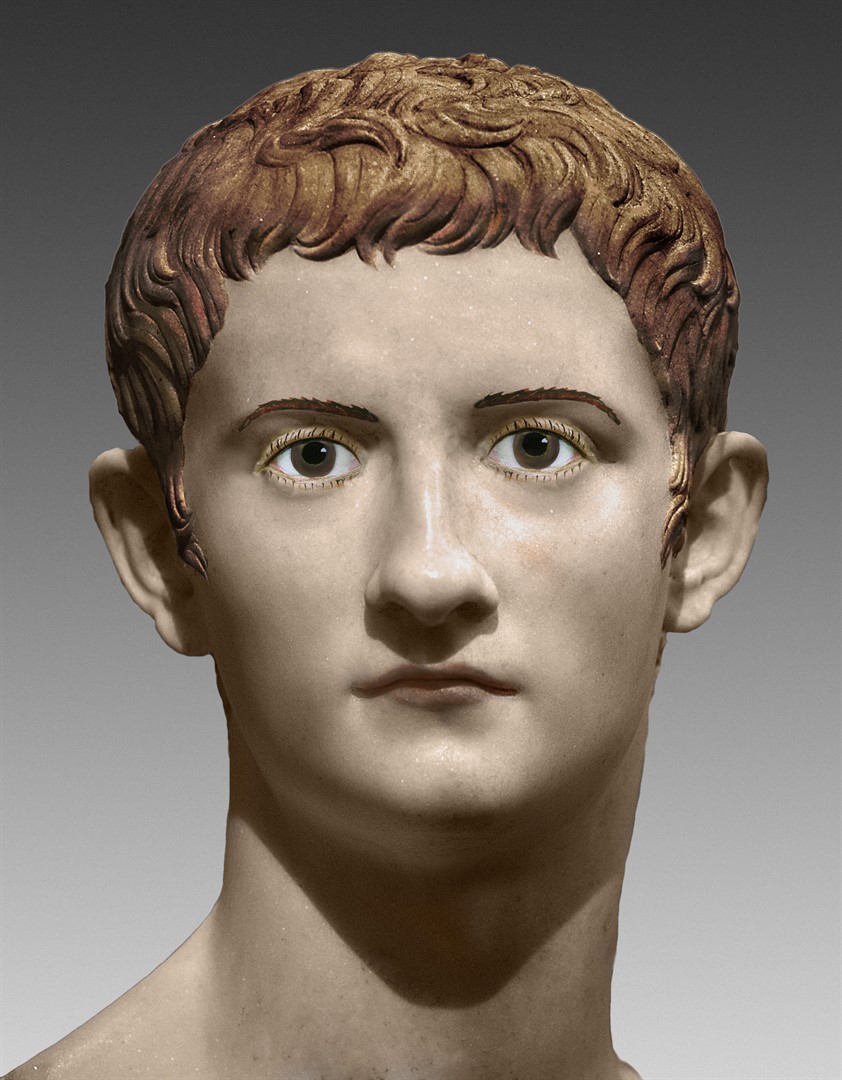

Rome is famous for infrastructure – aqueducts, cranes, roads, concrete, and central heating – but not scientific theory. The usual story is that Roman thought was too practical, too hierarchical, uninterested in pure understanding.

One text complicates that story: De Architectura, a ten-volume treatise by Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, written during the reign of Augustus. Often described as a manual for builders, De Architectura is far more than a how-to. It is a theoretical framework for knowledge, part engineering handbook, part philosophy of science.

Vitruvius was no scientist, but his ideas come astonishingly close to the scientific method. He describes devices like the Archimedean screw or the aeolipile, a primitive steam engine. He discusses acoustics in theater design, and a cosmological models passed down from the Greeks. He seems to describe vanishing point perspective, something seen in some Roman art of his day. Most importantly, he insists on a synthesis of theory, mathematics, and practice as the foundation of engineering. His describes something remarkably similar to what we now call science:

“The engineer should be equipped with knowledge of many branches of study and varied kinds of learning… This knowledge is the child of practice and theory. Practice is the continuous and regular exercise of employment… according to the design of a drawing. Theory, on the other hand, is the ability to demonstrate and explain the productions of dexterity on the principles of proportion…”

“Engineers who have aimed at acquiring manual skill without scholarship have never been able to reach a position of authority… while those who relied only upon theories and scholarship were obviously hunting the shadow, not the substance. But those who have a thorough knowledge of both… have the sooner attained their object and carried authority with them.”

This is more than just a plea for well-rounded education. H e gives a blueprint for a systematic, testable, collaborative knowledge-making enterprise. If Vitruvius and his peers glimpsed the scientific method, why didn’t Rome take the next step?

The intellectual capacity was clearly there. And Roman engineers, like their later European successors, had real technological success. The problem, it seems, was societal receptiveness.

Science, as Thomas Kuhn famously brough to our attention, is a social institution. It requires the belief that man-made knowledge can displace received wisdom. It depends on openness to revision, structured dissent, and collaborative verification. These were values that the Roman elite culture distrusted.

When Vitruvius was writing, Rome had just emerged from a century of brutal civil war. The Senate and Augustus were engaged in consolidating power, not questioning assumptions. Innovation, especially social innovation, was feared. In a political culture that prized stability, hierarchy, and tradition, the idea that empirical discovery could drive change likely felt dangerous.

We see this in Cicero’s conservative rhetoric, in Seneca’s moralism, and in the correspondence between Pliny and Trajan, where even mild experimentation could be viewed as subversive. The Romans could build aqueducts, but they wouldn’t fund a lab.

Like the Islamic world centuries later, Rome had scholars but not systems. Knowledge existed, but the scaffolding to turn it into science – collective inquiry, reproducibility, peer review, invitations for skeptics to refute – never emerged.

Vitruvius’s De Architectura deserves more attention, not just as a technical manual but as a proto-scientific document. It suggests that the core ideas behind science were not exclusive to early modern Europe. They’ve flickered into existence before, in Alexandria, Baghdad, Paris, and Rome, only to be extinguished by lack of institutional fit.

That science finally took root in the 17th century had less to do with discovery than with a shift in what society was willing to do with discovery. The real revolution wasn’t in Newton’s laboratory, it was in the culture.

Rome’s Modern Echo?

It’s worth asking whether we’re becoming more Roman ourselves. Today, we have massively resourced research institutions, global scientific networks, and generations of accumulated knowledge. Yet, in some domains, science feels oddly stagnant or brittle. Dissenting views are not always engaged but dismissed, not for lack of evidence, but for failing to fit a prevailing narrative.

We face a serious, maybe existential question. Does increasing ideological conformity, especially in academia, foster or hamper science?

Obviously, some level of consensus is essential. Without shared standards, peer review collapses. Climate models, particle accelerators, and epidemiological studies rely on a staggering degree of cooperation and shared assumptions. Consensus can be a hard-won product of good science. And it can run perilously close to dogma. In the past twenty years we’ve seen consensus increasingly enforced by legal action, funding monopolies, and institutional ostracism.

String theory may (or may not) be physics’ great white whale. It’s mathematically exquisite but empirically elusive. For decades, critics like Lee Smolin and Peter Woit have argued that string theory has enjoyed a monopoly on prestige and funding while producing little testable output. Dissenters are often marginalized.

Climate science is solidly evidence-based, but responsible scientists point to constant revision of old evidence. Critics like Judith Curry or Roger Pielke Jr. have raised methodological or interpretive concerns, only to find themselves publicly attacked or professionally sidelined. Their critique is labeled denial. Scientific American called Curry a heretic. Lawsuits, like Michael Mann’s long battle with critics, further signal a shift from scientific to pre-scientific modes of settling disagreement.

Jonathan Haidt, Lee Jussim, and others have documented the sharp political skew of academia, particularly in the humanities and social sciences, but increasingly in hard sciences too. When certain political assumptions are so embedded, they become invisible. Dissent is called heresy in an academic monoculture. This constrains the range of questions scientists are willing to ask, a problem that affects both research and teaching. If the only people allowed to judge your work must first agree with your premises, then peer review becomes a mechanism of consensus enforcement, not knowledge validation.

When Paul Feyerabend argued that “the separation of science and state” might be as important as the separation of church and state, he was pushing back against conservative technocratic arrogance. Ironically, his call for epistemic anarchism now resonates more with critics on the right than the left. Feyerabend warned that uniformity in science, enforced by centralized control, stifles creativity and detaches science from democratic oversight.

Today, science and the state, including state-adjacent institutions like universities, are deeply entangled. Funding decisions, hiring, and even allowable questions are influenced by ideology. This alignment with prevailing norms creates a kind of soft theocracy of expert opinion.

The process by which scientific knowledge is validated must be protected from both politicization and monopolization, whether that comes from the state, the market, or a cultural elite.

Science is only self-correcting if its institutions are structured to allow correction. That means tolerating dissent, funding competing views, and resisting the urge to litigate rather than debate. If Vitruvius teaches us anything, it’s that knowing how science works is not enough. Rome had theory, math, and experimentation. What it lacked was a social system that could tolerate what those tools would eventually uncover. We do not yet lack that system, but we are testing the limits.

Recent Comments