Posts Tagged travel

Things to See in Palazzo Massimo

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Art, History of Christianity on November 10, 2025

Mike and Andrea visit Rome this week. Here’s what I think they should see in Museo Nazionale Romano, Palazzo Massimo. Not that I’d try to push my taste on anyone.

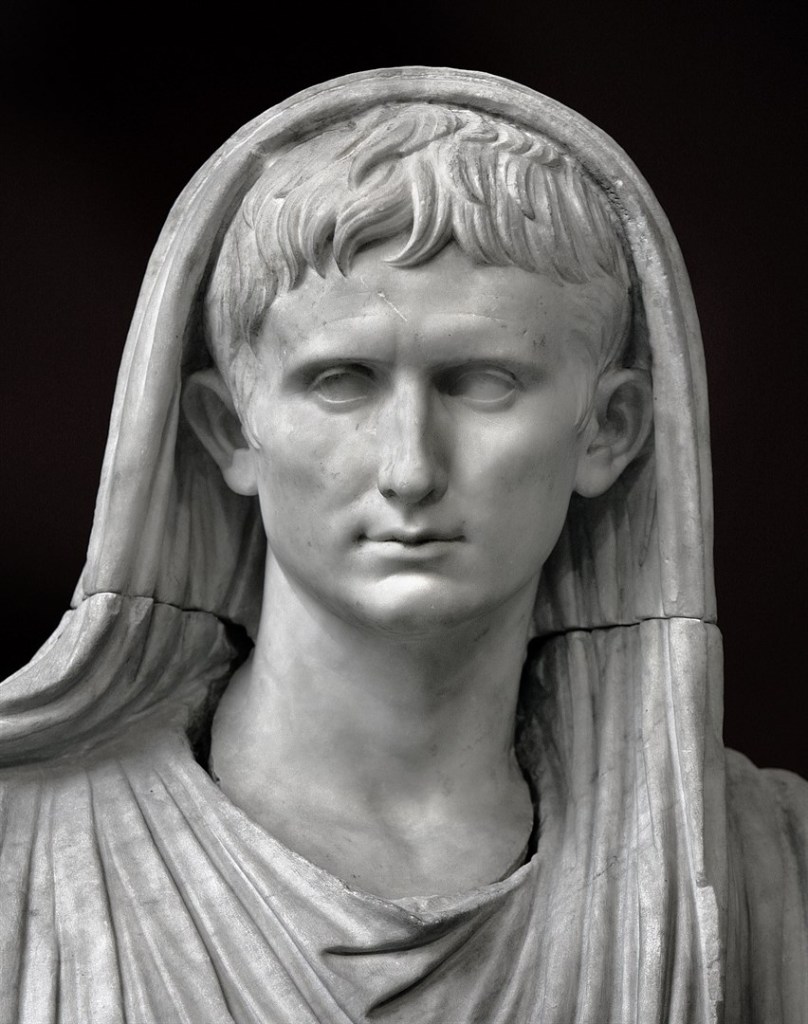

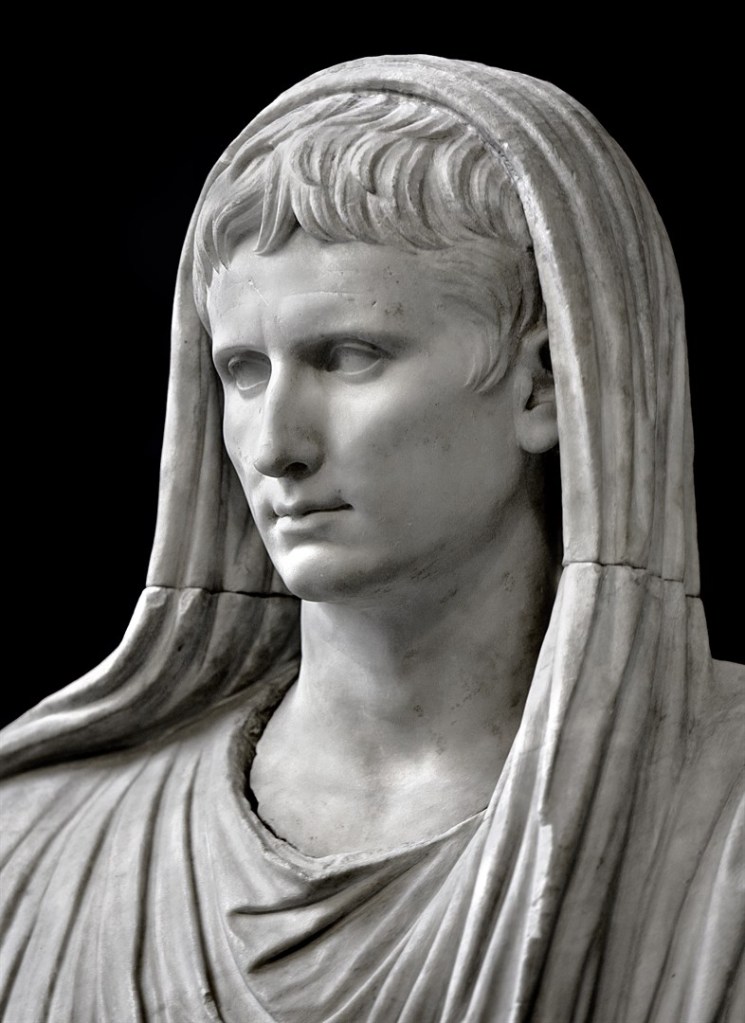

The Via Labicana Augustus

The Via Labicana Augustus was discovered in 1910 near the Via Labicana, southeast of Rome. It probably dates to 12 BCE, the year Augustus became Pontifex Maximus, chief priest of Rome.

The statue shows him veiled, performing a sacrifice, wearing the toga pulled over his head in the ritual gesture known as capite velato. Unlike the heroic, idealized Augustus of Prima Porta, this image presents him not as a godlike conqueror but as the pious restorer of Rome’s religious traditions. The face retains a calm, idealized realism – a softened continuation of late Republican verism – while the body’s smooth drapery and composed stance convey dignity and divine favor.

The piece reveals Augustus’s political strategy of merging personal authority with religious legitimacy. By showing himself as priest rather than warrior, he presented his rule as moral renewal and continuity with the Republic’s sacred traditions, rather than naked monarchy.

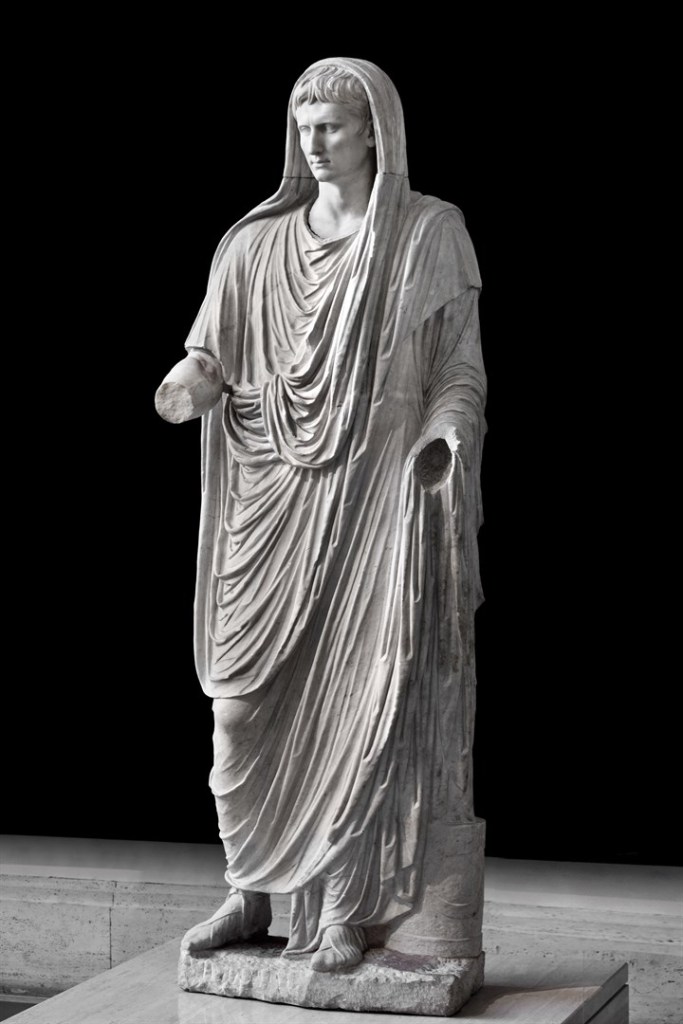

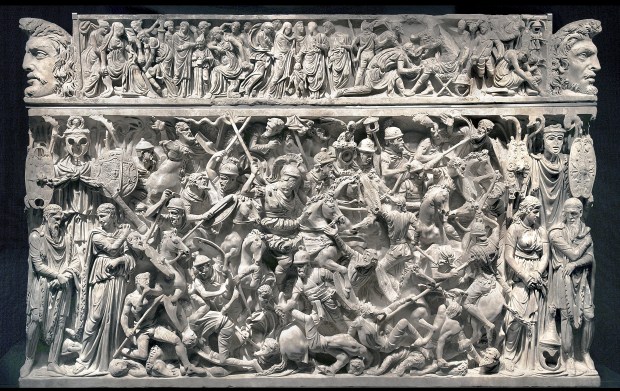

The Portonaccio Sarcophagus

The Portonaccio Sarcophagus, carved in high relief around 180-190 CE, is one of the most elaborate Roman sarcophagi from the late second century CE. It was discovered in a tomb in 1931 near the ancient Via Tiburtina in the Portonaccio area of Rome.

The front is a dense, chaotic battle scene. Roman soldiers clash with barbarians in a tangle of limbs, shields, and horses. There’s no clear spatial depth, just a frenzied mass of combat, carved almost in relief upon relief. At the center stands the Roman general, larger and calmer than the rest, commanding order amid chaos. His face is idealized, yet individualized; his bare head suggests he may have died before receiving a victory crown.

This style marks a shift from the classical order of earlier art to the expressive, almost abstract energy of late imperial sculpture. It reflects the constant warfare and political instability of the era. It likely commemorated General Aulus Iulius Pompilius, who served under Marcus Aurelius.

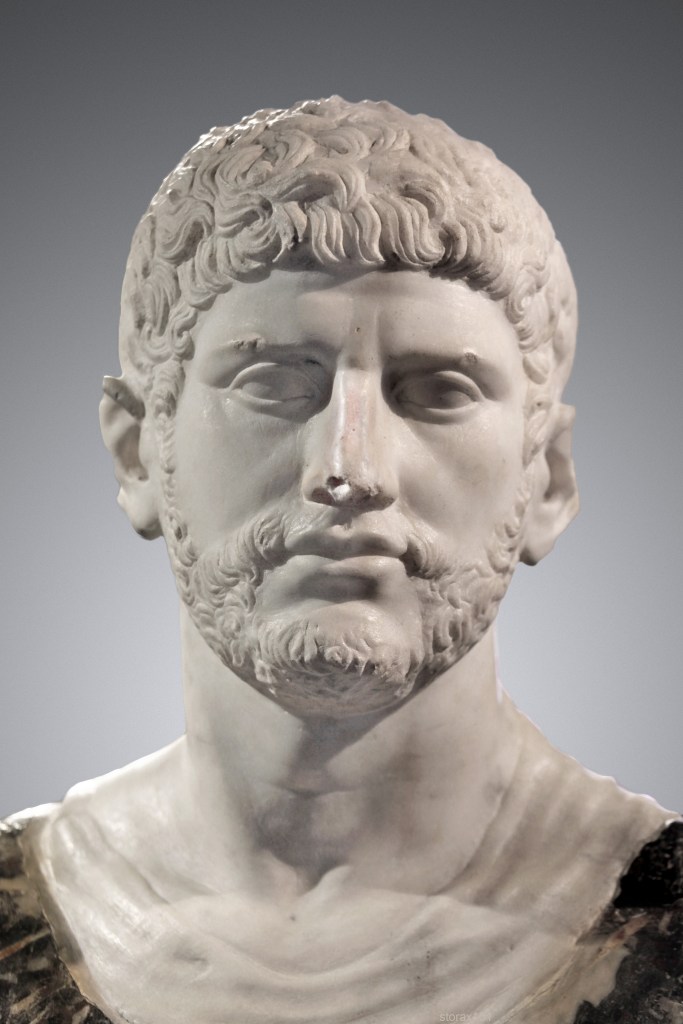

Colossal Bust of Gordian III

The colossal marble bust of Gordian III presents a striking – if not bizarre – image of the boy-emperor struggling to embody imperial gravitas. Created around AD 244, it reflects the tension between youthful vulnerability and the formal ideals of Roman authority.

Gordian III came to the throne after a cascade of assassinations during the “Year of the Six Emperors.” The sculptor has rendered him with the smooth, unlined face of an adolescent, but framed by the austere, hieratic composition typical of imperial portraiture – short military haircut, heavy-lidded eyes gazing slightly upward, and a thick neck suggesting strength he did could not have possessed. The result is almost tragic: the image insists on imperial permanence while hinting at fragility.

Stylistically, the bust belongs to the late Severan, early soldier-emperor phase, where portraiture shifts from the individualized realism of the Antonines to a more schematic, abstract treatment of features. The deep drilling of the hair and the intense, static expression anticipate the hard linearity of third-century imperial art.

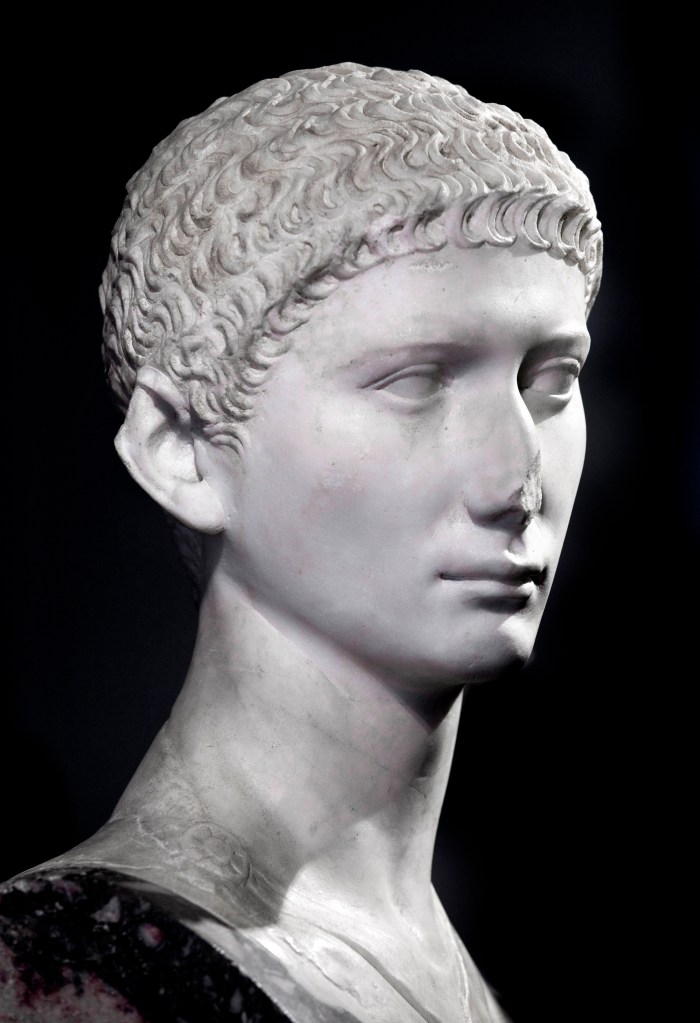

The Charioteers

The charioteer portrait busts date from the early fourth century CE and depict professional aurigae – chariot racers who were the sports celebrities of late imperial Rome.

These busts show men with distinctive attributes of their trade: short, tightly curled hair, intense gazes, and tunics bound with leather straps across the chest, used to secure their protective harnesses during races. The faces are individualized, confident, and slightly idealized, conveying both athletic vigor and the proud self-awareness of public fame.

They likely commemorated successful drivers from the great Roman circuses, perhaps freedmen who had risen to wealth and status through racing. The style, with its crisp carving and alert expression, reflects late Roman portraiture’s mix of realism and formal abstraction – an art no longer concerned with classical balance, but with projecting charisma and presence.

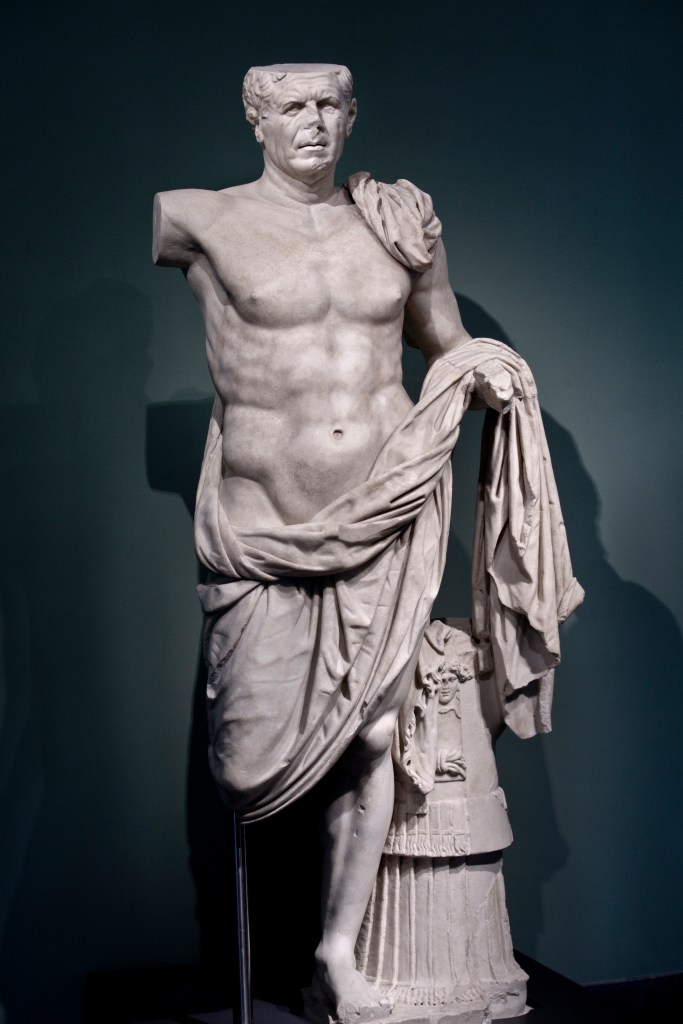

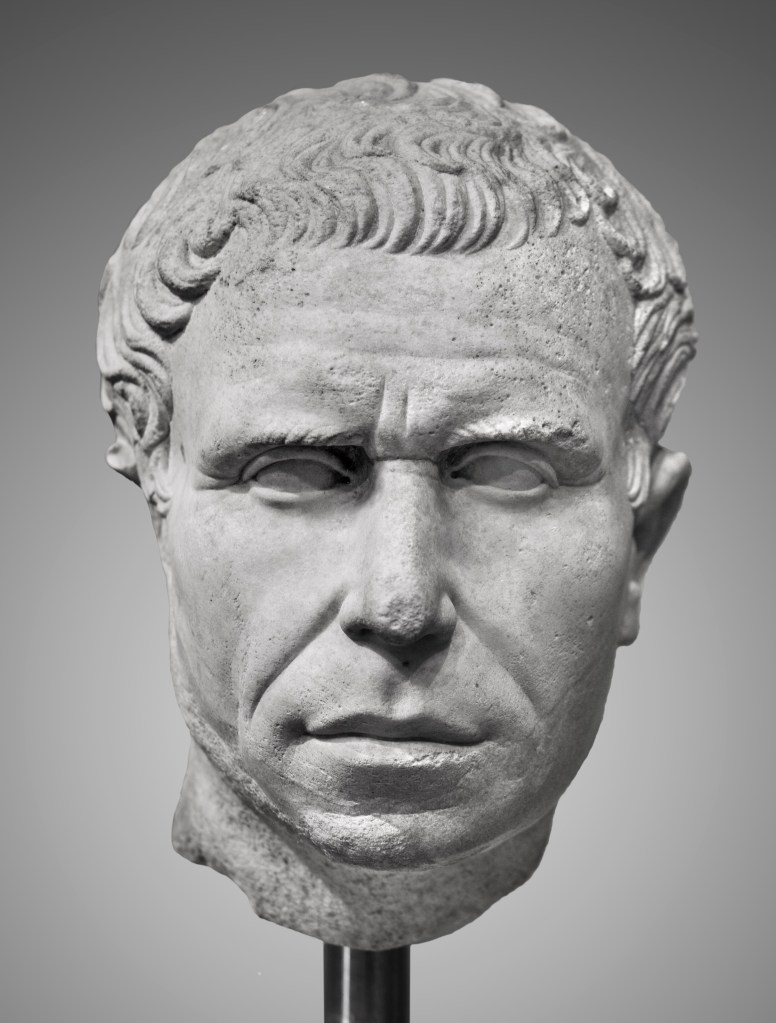

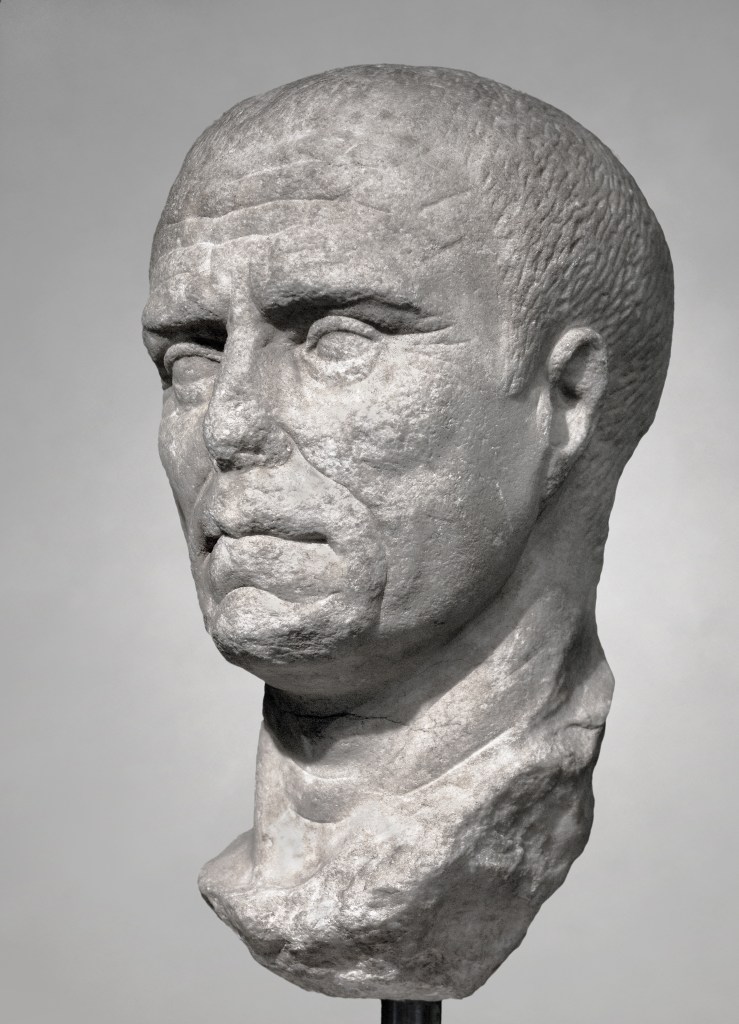

Republicans

The so-called General from Tivoli (Terme inv. 106513) was found beneath the Temple of Hercules in 1925. Dating to about 70 – 90 BC, he was probably a lieutenant of Sulla. The late-Republican portrait busts (Inv. 112301 and 114759) are famous for their verism – a style emphasizing unidealized realism. Rather than the smooth, youthful perfection of Greek sculpture, Roman patrons in this period wanted faces that looked weathered and unmistakably mortal. Eyes were often sharply undercut and hollowed to give depth and intensity. Cheeks could appear gaunt, lips thin and compressed, necks stringy. The overall effect was one of disciplined austerity and civic virtue – a face hardened by service to the Republic.

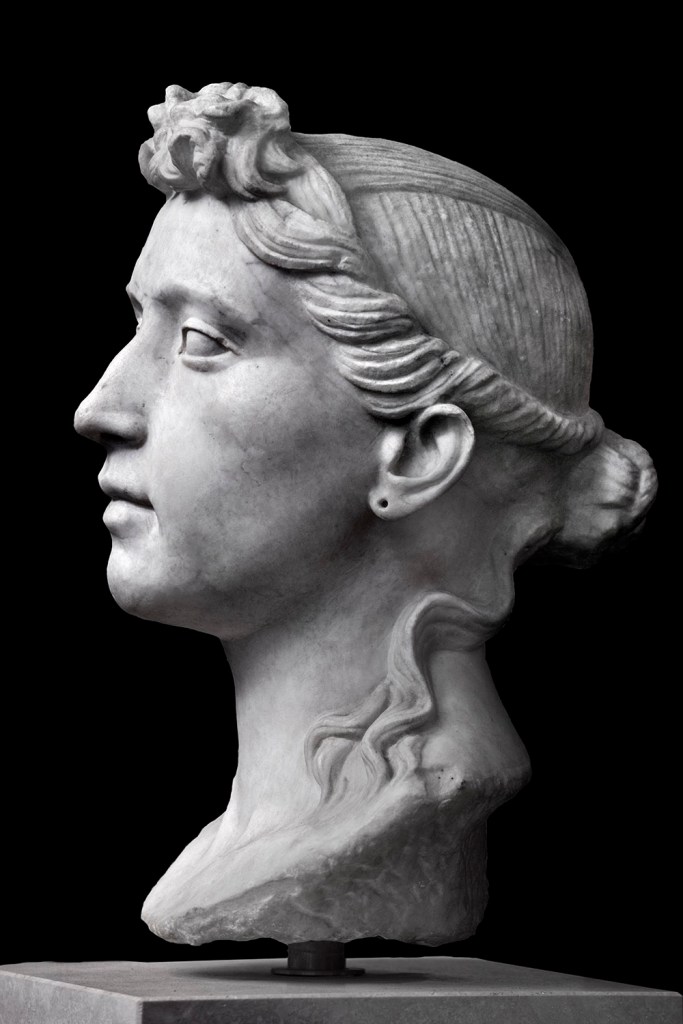

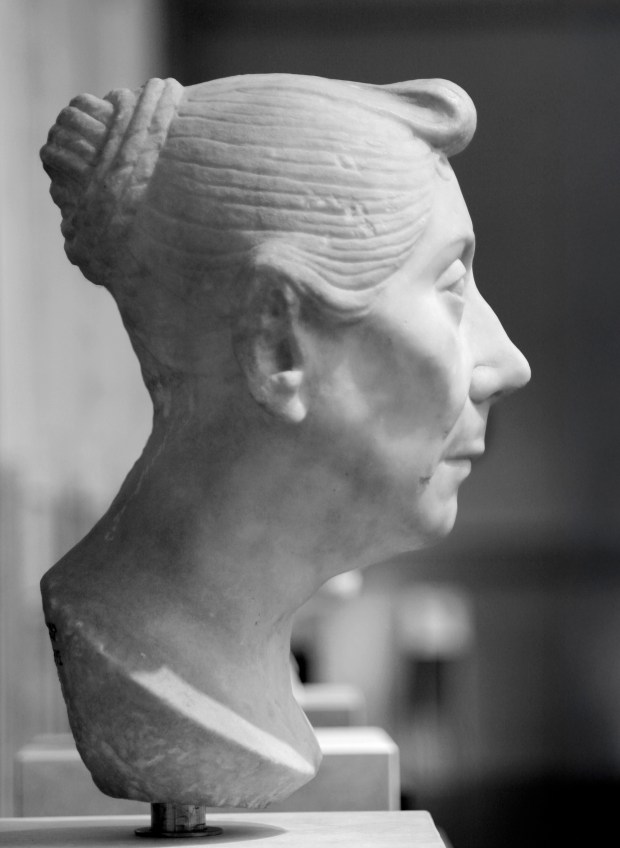

The young woman’s elaborate hairstyle (inv. 125591, just above) is a social signal, suggesting she belonged to a wealthy family or wanted to look the part. The combination of a classicizing ideal face with a detailed fashionable hairstyle suggests a woman who wants to present both grace and her social status. That blend of realism and idealization is typical of the late republic.

This was more selective exaggeration than realism. These men were advertising moral qualities: gravitas, virtus, fides. By the time of Caesar, you see a blending of this verism with a hint of idealization, anticipating the smooth, godlike Augustan portraits to come.

Speaking of late Republicans, this marble portrait of an elderly woman with her hair in a bun brings to mind another later Republican – Ronald Reagan.

The Sarcophagus of Marcus Claudianus

The continuous-frieze sarcophagus of Marcus Claudianus shows New Testament scenes on its front; and New and Old Testament scenes on its lid, along with pagan elements. The grape harvest imagery on the lid is ambiguous; it appears on pagan and Christian sarcophagi with identical elements. From left to right on the lid: Jesus nativity scene, sacrifice of Isaac, inscription naming the deceased, image of the deceased as scholar, grape harvest scene.

Carvings on the front of the sarcophagus: Arrest of Peter (Acts 12:3), miracle of water and wine (with possible baptism reference, John 2:1), orant figure, miracle of loaves (Mark 6:30–44, Matt 14:13–21, Luke 9:10–17, John 6:1–14), healing a man born blind (John 9:1), prediction of Peter’s denial (Mark 14:27–31, Matt 26:30–35, Luke 22:31–34, John 13:36–38), resurrection of Lazarus (John 11:1), and supplication of Lazarus’s sister (John 11:32).

The scenes on this sarcophagus include several apparent departures from scriptural miracle stories. Jesus appears in three places as magician, using a wand to perform miracles. He stands above five baskets of bread, a number consistent with most sarcophagi of its age but inconsistent with either of the loaves-and-fish scriptural pairs, where the remaining baskets number seven and twelve (Matthew 4:17, Matthew 15:34). This could have been a choice made by the sculptor for purely artistic reasons. The orant figure in the center is similar to those seen on earlier gravestones, and does not seem to be a scriptural reference. This posture is similar to that of the three youths in the furnace and the common sarcophagus scene of Jesus passing the new law to Peter and Paul (non-scriptural).

The Marcus Claudianus sarcophagus stands out for the prominence of Johannine-only imagery – Lazarus, the man born blind, Cana – scenes that are either uniquely Johannine or given distinct theological weight in that gospel. I don’t think you’ll hear this from anyone but me. I love this sarc for this reason. Compared to the sarcophagi from the Vatican necropolis, whose iconography often centers on synoptic or composite miracle cycles (feeding, healing, Jonah, Daniel, Good Shepherd), this sarc shows a notable shift toward Christological revelation rather than simple miracle narrative.

That shift says to me: mid-4th-century context, when Johannine motifs had become the backbone of Christian funerary theology. By that time, art was turning from generic symbols of deliverance to narratives that expressed Christ as Logos and life-giver, echoing themes prominent in the theological debates of the post-Nicene generation. The Lazarus scene, for example, takes on explicit resurrection connotations, and the healing of the blind man becomes an emblem of illumination through baptism – precisely the kind of allegorical reading developed in the decades after Constantine.

Earlier dating has been given by some scholars. Bunk. That impulse reflects anxiety over the scarcity of securely dated pre-Constantinian Christian monuments in Rome. Stylistically and iconographically, the Claudianus piece sits more naturally with sarcophagi of the 340s-360s: compressed compositions, monumental heads, frontal orant, and a selective, theological rather than narrative use of miracle scenes. And that’s probably more than you wanted to know about a topic I find fascinating because of what it says about modern Catholicism.

Bronze Athletes

The bronze athletes date from the Hellenistic period (second to first century BCE) convey the victory, exhaustion and fleeting nature of athletic glory.

The most famous of them, the Terme Boxer, was discovered on the Quirinal Hill in 1885. He sits slumped, body still powerful but spent, his face swollen and scarred, his hands wrapped in leather thongs. The artist cast every cut and bruise in bronze, even inlaid copper to suggest blood and wounds. Yet his expression is not defeat but endurance – a man who’s given everything to the arena.

Nearby, the Hellenistic Prince (or Terme Ruler), found in the same area, stands upright and nude, the counterpart to the seated boxer. His stance is heroic but weary, his gaze detached. Together the two figures tell both a moral story and a physical one: the the beauty and cost of strength.

These bronzes were likely imported to Rome as prized Greek originals or high-quality copies for a wealthy patron’s villa. They embody the Greek ideal of athletic excellence reframed through Roman admiration for the discipline and suffering behind it.

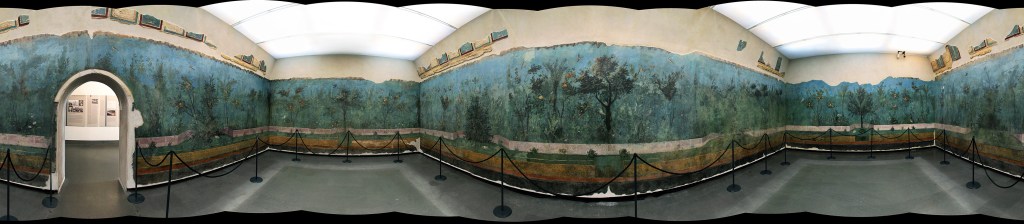

Wall Paintings/Frescoes

The villa wall paintings in Palazzo Massimo form one of the richest surviving narratives of Roman domestic life and taste. Most come from suburban villas around Rome, dating from the late Republic through the early Empire, and they recreate the visual world of elite Roman interiors.

The centerpiece is the set from Livia’s Villa at Prima Porta, discovered in 1863. The walls depict an illusionistic garden in full bloom – fruit trees, flowers, birds, and a soft blue sky.

Other rooms, such as those from the Villa of Farnesina, show mythological scenes, architectural vistas, and richly colored panels framed by columns and imaginary shrines. These follow the Second and Third Styles of Roman wall painting: first creating deep, theatrical perspective, then shifting to flatter, more decorative compositions filled with miniature landscapes and floating figures.

Taken together, the frescoes chart Rome’s transition from the austere republican taste for illusionistic space and Greek motifs to the sophisticated imperial language of myth, luxury, and controlled fantasy.

Cristo Docente

The Cristo Docente (Teaching Christ) clearly shows a youthful, androgynous body with small breasts. This is visual language flowing directly from Greco-Roman conventions of the philosopher, ephebe, or Apollo rather than an ethnographically accurate depiction of any historical Jesus. This one of the earliest depictions of Jesus, and a very rare example of Christian art not associated with burial. I wonder what the Vatican would trade for it.

Early Christian artists weren’t attempting realism; they were translating abstract theological ideas into iconic forms the viewer would recognize. The effeminate traits signal spiritual rather than biological qualities – gentleness, wisdom, eternal youth – while the frontal, often seated or teaching pose evokes authority and composure. In that cultural moment, a physically idealized, effeminate figure would convey the moral and divine authority expected of a teacher or savior without challenging Roman notions of masculinity, which were more flexible in the context of idealized youth and divinity.

The Christian anxiety that arises from this piece crack me up. Modern viewers, steeped in historical or doctrinal literalism, try to read the image literally. That’s a projection: the image is a theological construction, not an ethnographic one. Christian art critics, especially in the early 20th century, bristled at the iconography and tried to brush the thing off as a young girl posing as a scholar, rather than relaxing into the idea that early Christians weren’t like them.

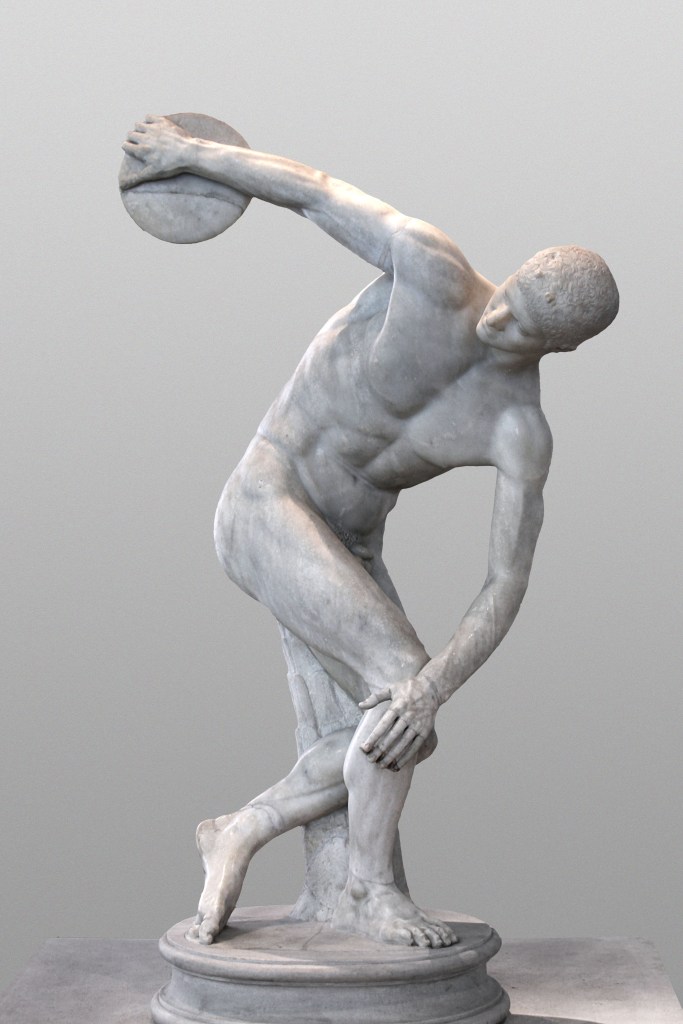

The Discobulus

This discobolus is interesting because it’s a Roman copy of a Greek original (traditionally attributed to Myron, mid-5th century BCE) but reinterpreted in a Roman context. Several points stand out:

Roman taste for idealized athleticism – Unlike the athletes that highlight strain and fatigue, the Discobolus captures frozen, perfect form in mid-action, emphasizing harmony, proportion, and controlled energy. The figure is taut, but serene, a demonstration of mastery over both body and motion.

Technical virtuosity – The sculpture compresses a dynamic twist of the torso and rotation of limbs into a balanced composition. The Massimo copy preserves this elegance while subtly softening the muscular definition compared with Hellenistic copies that exaggerate tension.

Cultural resonance in Rome – Displaying this statue in a Roman villa or public space signaled the moral and civic ideals associated with disciplined youth, athletic virtue, and controlled action—qualities the Roman elite wanted to project.

Roman copy as a lens on reception – we see how Romans interpreted Greek originals, choosing what to preserve, emphasize, or downplay. Unlike more dramatic Hellenistic works, this Discobolus shows restraint, aligning with Roman preferences for clarity, proportion, and intelligibility over theatricality. It’s a visual bridge between Greek athletic ideal and Roman moral-aesthetic ideology.

Bronze from Caligula’s Ships

The bronze fittings come from the two grand ceremonial vessels built in the lake of Lake Nemi, ordered by Gaius Caligula around AD 37-41. By commissioning such a floating palace, Caligula aligned himself with Hellenistic kings and with the mastery of nature. The bronzes speak that language of luxury and sacerdotal authority.

The vessels and their fittings were masterpieces of maritime technology, supported by massive beams, outriggers, twin rudders, and elaborate decoration. The bronze protomes were integrated in the structural and mechanical system of the ship (rudders, beams, mooring rings). Here is the transition from Republic to Imperial ornamentation in full flourish – Roman taste for Hellenistic luxury, combined with native iconography. The bronzes bridge functional object, architectural ornament, and political symbol.

The Arch of Constantine

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Art on October 31, 2025

This is for Mike and Andrea, on their first visit to Rome.

Some people take up gardening. I dug into the Arch of Constantine. Deep. I’ll admit it, I got a little obsessed. What started as a quick look turned into a full dig through the dust of Roman politics as seen by art historians and classicists, writers with a gift for making the obvious sound profound and the profound impenetrable. Think of a collaboration between poets, lawyers, and a Latin thesaurus. One question led to another, and before I knew it, I was knee-deep in relief panels, inscriptions, and bitter academic feuds from 1903. If this teaser does anything for you, order a pizza and head over to my long version, revised today to incorporate recent scholarship, which is making great strides.

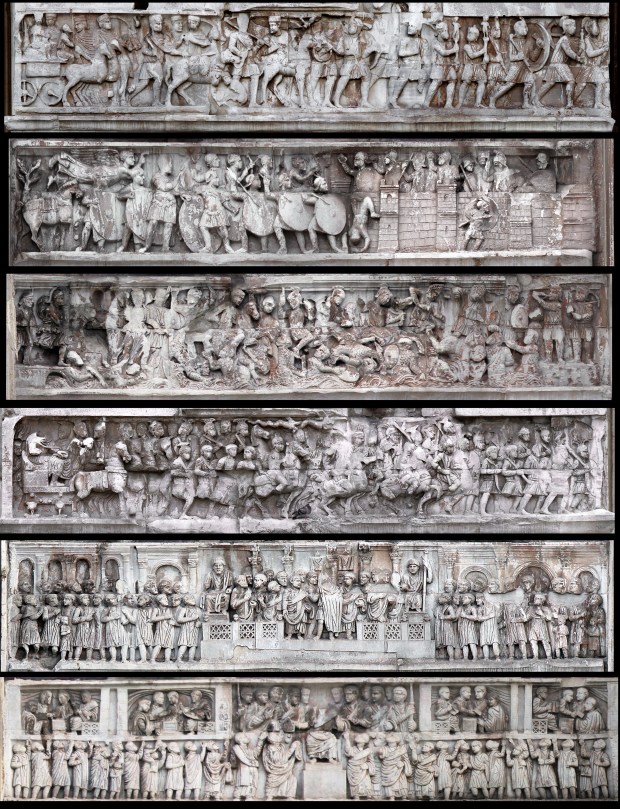

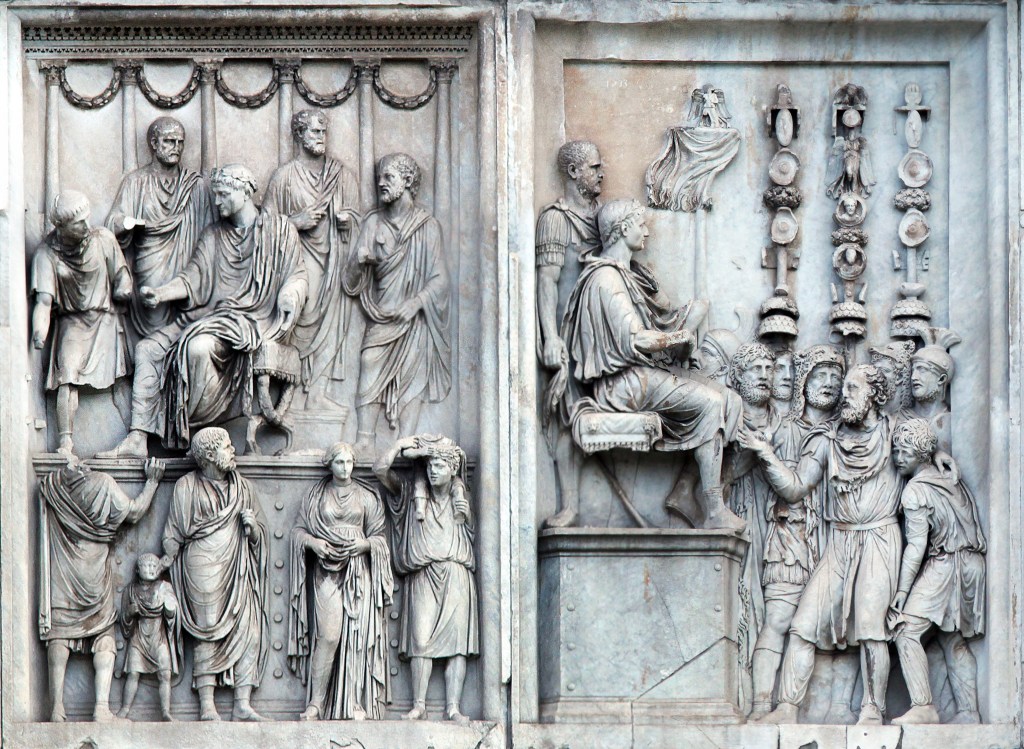

The Arch of Constantine stands just beside the Colosseum, massive and pale against the traffic. It was dedicated in 315 CE to celebrate Emperor Constantine’s victory over his rival Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge. On paper it’s a “triumphal arch,” but that’s not quite true. Constantine never held a formal triumph, and the monument itself was assembled partly from spare parts of older imperial projects.

Most of what you see wasn’t made for Constantine at all. His builders raided earlier monuments – especially from the reigns of Hadrian, Trajan, and Marcus Aurelius – and grafted those sculptures onto the new structure. Look closely and you can still spot the mismatches. The heads have been recut. A scene that once showed Emperor Hadrian hunting a lion now shows Constantine doing the honors, with a few clumsy adjustments to the drapery. Other panels, taken from Marcus Aurelius’s monuments, show the emperor addressing troops or granting clemency, only now it’s Constantine’s face and Constantine’s name.

These borrowed panels aren’t just decoration. They were carefully chosen to tie Constantine to the “good emperors” of the past, especially Marcus Aurelius, the philosopher-king. By mixing their images with his own, Constantine claimed continuity with Rome’s golden age while quietly erasing the messy years between.

The long strip of carving that wraps around the lower part of the arch is the one section made entirely for Constantine’s time. It’s a running narrative of his civil war against Maxentius. Starting on the west side, you can see Constantine setting out from Milan, soldiers marching behind his chariot. Around the corner, he besieges a walled city – probably Verona – and towers over his men, twice their size, a new kind of emperor who commands by sheer presence. The next panel shows the chaotic battle at the Milvian Bridge, where Maxentius’s troops drown in the Tiber while Constantine’s army presses forward. The story ends with Constantine entering Rome and addressing the citizens from a raised platform, a ruler both human and divine.

The figures look stiff and simplified compared to the older reliefs above them, but that’s part of the shift the arch represents. Art was moving away from naturalism toward symbolism. Constantine isn’t shown as an individual man but as an idea: the chosen ruler, the earthly image of divine authority.

That message runs through the inscription carved across the top. It declares that Constantine won instinctu divinitatis – “by divine inspiration.” The phrase is unique; no one had used it before. It’s deliberately vague, as if leaving room for different gods to take the credit. For pagans, it could mean Apollo or Sol Invictus. For Christians, it sounded like the hand of the one God. Either way, it announced a new kind of emperor, one who ruled not just with the favor of the gods but through them.

The Arch of Constantine isn’t simply a monument to a battle. It’s a scrapbook of Rome’s artistic past and a statement of political legitimacy. Read carefully, it is an early sign that the empire was in for religion, hard times, and down-sizing.

Photos and text copyright 2025 by William K Storage

I’m Only Neurotic When – Engineering Edition

Posted by Bill Storage in Commentary, Engineering & Applied Physics on October 7, 2025

The USB Standard of Suffering

The USB standard was born in the mid-1990s from a consortium of Intel, Microsoft, IBM, DEC, NEC, Nortel, and Compaq. They formed the USB Implementers Forum to create a universal connector. The four pins for power and data were arranged asymmetrically to prevent reverse polarity damage. But the mighty consortium gave us no way to know which side was up.

The Nielsen Norman Group found that users waste ten seconds per insertion. Billions of plugs times thirty years. We could have paved Egypt with pyramids. I’m not neurotic. I just hate death by a thousand USB cuts.

The Dyson Principle

I admire good engineering. I also admire honesty in materials. So naturally, I can’t walk past a Dyson vacuum without gasping. The thing looks like it was styled by H. R. Giger after a head injury. Every surface is ribbed, scooped, or extruded as if someone bred Google Gemini with CAD software, provided the prompt “manifold mania,” and left it running overnight. Its transparent canister resembles an alien lung. There are ducts that lead nowhere, fins that cool nothing, and bright colors that imply importance. It’s all ornamental load path.

To what end? Twice the size and weight of a sensible vacuum, with eight times the polar moment of inertia. (You get the math – of course you do.) You can feel it fighting your every turn, not from friction, but from ego. Every attempt at steering carries the mass distribution of a helicopter rotor. I’m not cleaning a rug, I’m executing a ground test of a manic gyroscope.

Dyson claims it never loses suction. Fine, but I lose patience. It’s a machine designed for showroom admiration, not torque economy. Its real vacuum is philosophical: the absence of restraint. I’m not neurotic. I just believe a vacuum should obey the same physical laws as everything else in my house. I’m told design is where art meets engineering. That may be true, but in Dyson’s case, it’s also where geometry goes to die. There’s form, there’s function, and then there’s what happens when you hire a stylist who dreams in centrifugal-manifold Borg envy.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Physics

No one but Frank Lloyd Wright could have designed these cantilevered concrete roof supports, the tour guide at the Robie House intoned reverently, as though he were describing Moses with a T-square. True – and Mr. Wright couldn’t have either. The man drew poetry in concrete, but concrete does not care for poetry. It likes compression. It hates tension and bending. It’s like trying to make a violin out of breadsticks.

They say Wright’s genius was in making buildings that defied gravity. True in a sense – but only because later generations spent fifty times his budget figuring ways to install steel inside the concrete so gravity and the admirers of his genius wouldn’t notice. We have preserved his vision, yes, but only through subterfuge and eternal rebar vigilance.

Considered the “greatest American architect of all time” by people who can name but one architect, Wright made it culturally acceptable for architects to design expressive, intensely personal museums. The Guggenheim continues to thrill visitors with a unique forum for contemporary art. Until they need the bathroom – a feature more of an afterthought for Frank. Try closing the door in there without standing on the toilet. Paris hotels took a cue.

The Interface Formerly Known as Knob

Somewhere, deep in a design studio with too much brushed aluminum and not enough common sense, a committee decided that what drivers really needed was a touch screen for everything. Because nothing says safety like forcing the operator of a two-ton vehicle to navigate a software menu to adjust the defroster.

My car had a knob once. It stuck out. I could find it. I could turn it without looking. It was a miracle of tactile feedback and simple geometry. Then someone decided that physical controls were “clutter.” Now I have a 12-inch mirror that reflects my fingerprints and shame. To change the volume, I have to tap a glowing icon the size of an aspirin, located precisely where sunlight can erase it. The radio tuner is buried three screens deep, right beside the legal disclaimer that won’t go away until I hit Accept. Every time I start the thing. And the Bluetooth? It won’t connect while the car is moving, as if I might suddenly swerve off the road in a frenzy of unauthorized pairing. Design meets an army of failure-to-warn attorneys.

Human factors used to mean designing for humans. Now it means designing obstacles that test our compliance. I get neurotic when I recall a world where you could change the volume by touch instead of prayer.

Automation Anxiety

But the horror of car automation goes deeper, far beyond its entertainment center. The modern car no longer trusts me. I used to drive. Now I negotiate. Everything’s “smart” except the decisions. I rented one recently – some kind of half-electric pseudopod that smelled of despair and fresh software – and tried to execute a simple three-point turn on a dark mountain road. Halfway through, the dashboard blinked, the transmission clunked, and without warning the thing threw itself into Park and set the emergency brake.

I sat there in the dark, headlamps cutting into trees, wondering what invisible crime I’d committed. No warning lights, no chime, no message – just mutiny. When I pressed the accelerator, nothing. Had it died of fright? Then I remembered: modern problems require modern superstitions. I turned it off and back on again. Reboot – the digital age’s holy rite of exorcism. It worked.

Only later did I learn, through the owner’s manual’s runic footnotes, that the car had seen “an obstacle” in the rear camera and interpreted it as a cliff. In reality it was a clump of weeds. The AI mistook grass for death.

So now, in 2025, the same species that landed on the Moon has produced a vehicle that prevents a three-point turn for my own good. Not progress, merely the illusion of it – technology that promises safety by eliminating the user. I’m not neurotic. I just prefer my machines to ask before saving my life by freezing in place as headlights come around the bend.

The Illusion of Progress

There’s a reason I carry a torque wrench. It’s not to maintain preload. It’s to maintain standards. Torque is truth, expressed in foot-pounds. The world runs on it.

Somewhere along the way, design stopped being about function and started being about feelings. You can’t torque a feeling. You can only overdo it. Hence the rise of things that are technically advanced but spiritually stupid. Faucets that require a firmware update, refrigerators with Twitter accounts. Cars that disable half their features because you didn’t read the EULA while merging onto the interstate.

I’m told this is innovation. No, it’s entropy with a bottomless budget. After the collapse, I expect future archaeologists to find me in a fossilized Subaru, finger frozen an inch from the touchscreen that controlled the wipers.

Until then, I’ll keep my torque wrench, thank you. And I’ll keep muting TikTok’s #lifehacks tag, before another self-certified engineer shows me how to remove stripped screws with a banana. I’m not neurotic. I’ve learned to live with people who do it wrong.

Don’t Skimp on Shoes

Posted by Bill Storage in Commentary on January 2, 2026

When I was a kid, mom and dad went out for the evening and told me that Frank, whom I hadn’t met, was going to stop by. He was dropping off some coins from his collection. He wanted us to determine whether these gold coins were legitimate, ninety percent gold, “.900 fineness,” as specified by the Coinage Act of 1837.

After the 1974 legalization of private gold ownership in the U.S., demand surged for pre-1933 American gold coins as bullion investments rather than numismatic curiosities. The market became jumpy, especially among buyers who cared only about intrinsic value. Counterfeit U.S. gold coins did exist. They were high-quality struck fakes, not crude castings, and they were made from real ninety percent gold alloy. Counterfeiters melted down common-date coins to produce rarer ones. Gold-plated base-metal fakes also existed, but those were cast, and Frank would never have fallen for them. We know that now. At the time, reliable information was thin on the ground.

The plan was to use Archimedes’ method. We’d weigh the coins, then dunk them in water and measure the displacement. Weight divided by displaced volume gives density. Ninety percent gold with ten percent copper comes out to 17.15 grams per cubic centimeter. Anything lower meant trouble.

The doorbell rang. Frank was a big guy in flannel shirt and jeans. He said he had something for my dad. I told him dad said he’d be coming. Frank handed me a small bag weighing five pounds – avoirdupois, not troy. About fifteen thousand dollars’ worth of gold at the time. You could buy a Corvette coupe, not the cheaper convertible, for six thousand. He handed me the bag, said thanks, and drove off in his pickup truck.

A few years ago I went on a caving trip to the Marble Mountains of northern California. The walk in didn’t look bad on paper. Five or six miles, maybe a couple thousand feet of elevation gain. With camping gear, food, and a load of heavy caving equipment, it turned out to be very bad indeed. I underestimated it, and paid for it.

A month before I’d been in Hawaii hiking to and through lava tubes in a recent flow, not the friendly pahoehoe kind but the boot-shredding a‘a stuff. A few days there destroyed a decent pair of boots. Desperate to make a big connection between two distant entrances, Doug drove me to Walmart, and I bought one of their industrial utility specials. It would get me through the day. It did. Our lava tube was four miles end to end.

I forgot about my boot situation until the Marble Mountains trip. At camp, as I was cutting sheets of moleskin to armor my feet for the hike out, I met a caver who knew my name and treated me as someone seasoned, someone who ought to know better. He looked down at my feet, laughed, and said, “Storage, you of all people, I figured wouldn’t wear cheap shoes into the mountains.” He figured wrong. I wore La Sportivas on the next trip.

What struck me as odd, I told my dad when he got home, wasn’t that Frank trusted a kid with fifteen thousand dollars in gold. It was that he drove a beat-up truck. I mentioned the rust.

“Yeah,” dad said. “But it’s got new tires.”

life, short-story, travel, writing

2 Comments