Science doesn’t proceeds in straight lines. It meanders, collides, and battles over its big ideas. Thomas Kuhn’s view of science as cycles of settled consensus punctuated by disruptive challenges is a great way to understand this messiness, though later approaches, like Imre Lakatos’s structured research programs, Paul Feyerabend’s radical skepticism, and Bruno Latour’s focus on science’s social networks have added their worthwhile spins. This piece takes a light look, using Kuhn’s ideas with nudges from Feyerabend, Lakatos, and Latour, at the ongoing debate over dietary salt, a controversy that’s nuanced and long-lived. I’m not looking for “the truth” about salt, just watching science in real time.

Dietary Salt as a Kuhnian Case Study

The debate over salt’s role in blood pressure shows how science progresses, especially when viewed through the lens of Kuhn’s philosophy. It highlights the dynamics of shifting paradigms, consensus overreach, contrarian challenges, and the nonlinear, iterative path toward knowledge. This case reveals much about how science grapples with uncertainty, methodological complexity, and the interplay between evidence, belief, and rhetoric, even when relatively free from concerns about political and institutional influence.

In The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Kuhn proposed that science advances not steadily but through cycles of “normal science,” where a dominant paradigm shapes inquiry, and periods of crisis that can result in paradigm shifts. The salt–blood pressure debate, though not as dramatic in consequence as Einstein displacing Newton or as ideologically loaded as climate science, exemplifies these principles.

Normal Science and Consensus

Since the 1970s, medical authorities like the World Health Organization and the American Heart Association have endorsed the view that high sodium intake contributes to hypertension and thus increases cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk. This consensus stems from clinical trials such as the 2001 DASH-Sodium study, which demonstrated that reducing salt intake significantly (from 8 grams per day to 4) lowered blood pressure, especially among hypertensive individuals. This, in Kuhn’s view, is the dominant paradigm.

This framework – “less salt means better health” – has guided public health policies, including government dietary guidelines and initiatives like the UK’s salt reduction campaign. In Kuhnian terms, this is “normal science” at work. Researchers operate within an accepted model, refining it with meta-analyses and Randomized Control Trials, seeking data to reinforce it, and treating contradictory findings as anomalies or errors. Public health campaigns, like the AHA’s recommendation of less than 2.3 g/day of sodium, reflect this consensus. Governments’ involvement embodies institutional support.

Anomalies and Contrarian Challenges

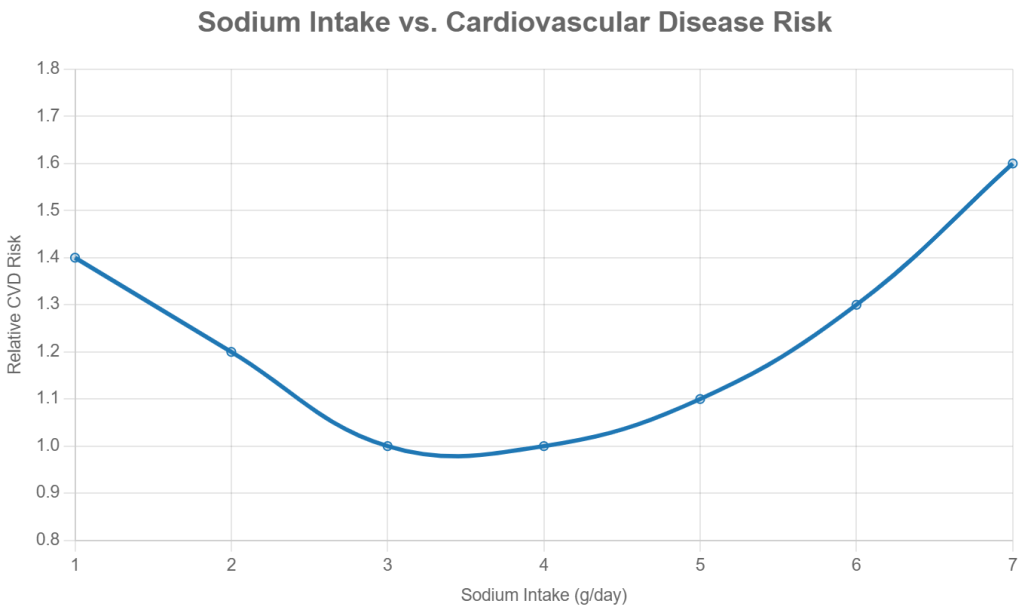

However, anomalies have emerged. For instance, a 2016 study by Mente et al. in The Lancet reported a U-shaped curve; both very low (less than 3 g/day) and very high (more than 5 g/day) sodium intakes appeared to be associated with increased CVD risk. This challenged the linear logic (“less salt, better health”) of the prevailing model. Although the differences in intake were not vast, the implications questioned whether current sodium guidelines were overly restrictive for people with normal blood pressure.

The video Salt & Blood Pressure: How Shady Science Sold America a Lie mirrors Galileo’s rhetorical flair, using provocative language such as “shady science” to challenge the establishment. Like Galileo’s defense of heliocentrism, contrarians in the salt debate (researchers like Mente) amplify anomalies to question dogma, sometimes exaggerating flaws in early studies (e.g., Lewis Dahl’s rat experiments) or alleging conspiracies (e.g., pharmaceutical influence). More in Feyerabend’s view than in Kuhn’s, this exaggeration and rhetoric might be desirable. It’s useful. It provides the challenges that the paradigm should be able to overcome to remain dominant.

These challenges haven’t led to a paradigm shift yet, as the consensus remains robust, supported by RCTs and global health data. But they highlight the Kuhnian tension between entrenched views and emerging evidence, pushing science to refine its understanding.

Framing the issue as a contrarian challenge might go something like this:

Evidence-based medicine sets treatment guidelines, but evidence-based medicine has not translated into evidence-based policy. Governments advise lowering salt intake, but that advice is supported by little robust evidence for the general population. Randomized controlled trials have not strongly supported the benefit of salt reduction for average people. Indeed, we see evidence that low salt might pose as great a risk.

Methodological Challenges

The question “Is salt bad for you?” is ill-posed. Evidence and reasoning say this question oversimplifies a complex issue: sodium’s effects vary by individual (e.g., salt sensitivity, genetics), diet (e.g., processed vs. whole foods), and context (e.g., baseline blood pressure, activity level). Science doesn’t deliver binary truths. Modern science gives probabilistic models, refined through iterative testing.

While randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have shown that reducing sodium intake can lower blood pressure, especially in sensitive groups, observational studies show that extremely low sodium is associated with poor health. This association may signal reverse causality, an error in reasoning. The data may simply reveal that sicker people eat less, not that they are harmed by low salt. This complexity reflects the limitations of study design and the challenges of isolating causal relationships in real-world populations. The above graph is a fairly typical dose-response curve for any nutrient.

The salt debate also underscores the inherent difficulty of studying diet and health. Total caloric intake, physical activity, genetic variation, and compliance all confound the relationship between sodium and health outcomes. Few studies look at salt intake as a fraction of body weight. If sodium recommendations were expressed as sodium density (mg/kcal), it might help accommodate individual energy needs and eating patterns more effectively.

Science as an Iterative Process

Despite flaws in early studies and the polemics of dissenters, the scientific communities continue to refine its understanding. For example, Japan’s national sodium reduction efforts since the 1970s have coincided with significant declines in stroke mortality, suggesting real-world benefits to moderation, even if the exact causal mechanisms remain complex.

Through a Kuhnian lens, we see a dominant paradigm shaped by institutional consensus and refined by accumulating evidence. But we also see the system’s limits: anomalies, confounding variables, and methodological disputes that resist easy resolution.

Contrarians, though sometimes rhetorically provocative or methodologically uneven, play a crucial role. Like the “puzzle-solvers” and “revolutionaries” in Kuhn’s model, they pressure the scientific establishment to reexamine assumptions and tighten methods. This isn’t a flaw in science; it’s the process at work.

Salt isn’t simply “good” or “bad.” The better scientific question is more conditional: How does salt affect different individuals, in which contexts, and through what mechanisms? Answering this requires humility, robust methodology, and the acceptance that progress usually comes in increments. Science moves forward not despite uncertainty, disputation and contradiction but because of them.

#1 by Anonymous on July 1, 2025 - 10:08 am

It’s been too long. As always, a pleasure to come across something you’ve thought about. Extending Kuhn’s Law more broadly into a more general law of human societies appears to be a good fit, although I have given it little thought.

A ramble on Galileo:

First, a greatly underappreciated man. After all, Newton’s famous three laws of motion could also be described as one or two Galilean with the remaining the Newtonians.

While Galileo’s embracing of Copernican mechanics was not well-thought of by certain members of the clergy, the reason he was placed under house arrest was not truly due to his heliocentric views. Rather, it was more a case of maybe-borderline hubris. Hubris being a crime of moral outrage and in this case the outraged party a long-time supporter and patron of Galileo, Maffeo V. Barberini who had become Pope Urban VIII (pretty sure it was VIII?).

In writing his book on a system of two bodies Galileo framed the subject as a set of Socratic Dialogs between a Copernican, a reasonably educated and smart laymen, and a geocentrist fool who all discuss their thoughts with Galileo. This was not an uncommon approach at the time. Anyhow, there is controversy as to whom the fool was intended to specifically represent, but the conceptual target was clear, anyone who believed in a geocentric view. Galileo’s handling of the fool’s (Simplico??) opinions was overly disparaging to the point of insult. Being brutally insulting to the views of one’s long-time patron, especially when said patron has become the Prince of Rome, was an approach Galileo had to have known was well beyond the Pale. Heresy was a convenient charge, not really the issue at hand. Had he been almost anyone else, he would have been executed. Had he taken a gentler tact, it likely would have never been an issue.

One can argue the moral right or wrong of Galileo’s adherence to what he saw as the truth in his writings, but such are arguments are simply irrelevant to the case of Galileo’s prosecution; better yet, I will borrow your [excellent] use of an expression, they are “ill-posed”.

Note on the book itself.

Most of the science in the book has held up decently well, especially considering it has been 400 years. However, one of the 4 sections of the book attempts to explain the motion of the Earth using tides. It was a complete mess, inconsistent and incorrect. In the forward to a translation of the Dialogs Einstein wrote:

“The fascinating arguments in the last conversation would hardly have been accepted as proof by Galileo, had his temperament not got the better of him.”

(https://web.archive.org/web/20070925083931/http://milestones.buffalolib.org/books/books/dialogo/impact.htm)

…it was also his temperament which got him into the pickle leading to his permanent house arrest.

#2 by Anonymous on July 1, 2025 - 10:10 am

I forgot to include my name in my overly long ramble, Tillman.

#3 by Bill Storage on July 1, 2025 - 10:41 am

Holy cow. Indeed a long time. Good to hear from you. Yep. Urban VIII. John Heilbron, who I interviewed here (https://themultidisciplinarian.com/2025/06/02/john-heilbron-interview-june-2012/) was the god of Galileo. His book of the same name is more thorough than the others that came out at the time (2012) on his relationship with Bellarmine and Barberini.

#4 by Bill Storage on July 1, 2025 - 10:42 am

Not overly long. Good stuff.

#5 by Atty at Purchasing on July 4, 2025 - 10:01 am

could an rct even be designed that looks at over time the same body that seemed to benefit from salt reduction in time would need to further reduce as the body adapts to each successive reduction of salt? Seems like there’s so many confounders confounding study designers, well meaning or not.