Bill Storage

This user hasn't shared any biographical information

I’m Only Neurotic When You Do It Wrong

Posted in Commentary on October 6, 2025

I don’t think of myself as obsessive. I think of myself as correct. Other people confuse those two things because they’ve grown comfortable in a world that tolerates sloppiness. I’m only neurotic when you do it wrong.

In Full Metal Jacket, Stanley Kubrick mocks the need for precision. Gunnery Sergeant Hartman, played by R. Lee Ermey, has a strict regimen for everything from cellular function on up. Kubrick has Hartman tell Private Pyle, “If there is one thing in this world that I hate, it is an unlocked footlocker!” Of course, Hartman hates an infinity of things, but all of them are things we secretly hate too. For those who missed the point, Kubrick has the colonel later tell Joker, “Son, all I’ve ever asked of my Marines is that they obey my orders as they would the word of God.”

The facets of life lacking due attention to detail are manifold, but since we’ve started with entertainment, let’s stay there. Entertainment budgets dwarf those of most countries. All I’ve ever asked of screenwriters is to hire historical consultants who can spell anachronism. Kubrick is credited with meticulous attention to detail. Hah. He might learn something from Sgt. Hartman. In Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon duel scene, a glance over Lord Bullingdon’s shoulder reveals a map with a decorative picture of a steam train, something not invented for another fifty years. The scene of the Lyndon family finances shows receipts bound by modern staples. Later, someone mentions the Kingdom of Belgium. Oops. Painterly cinematography and candlelit genius, yes – but the first thing that comes to mind when I hear Barry Lyndon is the Dom Pérignon bottle glaring on the desk, half a century out of place.

Soldiers carry a 13-star flag in The Patriot. Troy features zippers. Braveheart wears a kilt. Andy Dufresne hides his tunnel behind a Raquel Welch poster in Shawshank Redemption. Forrest Gump owns Apple stock. Need I go on? All I’ve ever asked of filmmakers is that they get every last detail right. I’m only neurotic when they blow it.

Take song lyrics. These are supposedly the most polished, publicly consumed lines in the English language. Entire industries depend on them. There are producers, mixers, consultants galore – whole marketing teams – and yet no one, apparently, ever said, “Hold on, Jim, that doesn’t make any sense.

Jim Morrison, I mean. Riders on the Storm is moody and hypnotic. On first hearing I settled in for what I knew, even at twelve, was an instant classic. Until he says of the killer: “his brain is squirming like a toad.” Not the brain of a toad, not a brain that toaded. There it was – a mental image of a brain doing a toad impression. The trance was gone. Minds squirm, not toads. Toads hold still, then hop, then hold still again. Rhyming dictionaries existed in 1970. He could have found anything else. Try: “His mind was like a dark abode.” Proofreader? Editor? QA department? Peer review? Fifty years on, I still can’t hear it without reliving my early rock-crooner trauma.

Rocket Man surely ranks near Elton’s John’s best. But clearly Elton is better at composition than at contractor oversight. Bernie Taupin wrote, “And all this science, I don’t understand.” Fair. But then: “It’s just my job, five days a week.” So wait, you don’t understand science, but NASA gave you a five-day schedule and weekends off because of what skill profile? Maybe that explains Challenger and Columbia.

Every Breath You Take by The Police. It’s supposed to be about obsession, but Sting (Sting? – really, Gordon Sumner?) somehow thought “every move you make, every bond you break” sounded romantic. Bond? Who’s out there breaking bonds in daily life? Chemical engineers? Sting later claimed people misunderstood it, but that’s because it’s badly written. If your stalker anthem is being played at weddings, maybe you missed a comma somewhere, Gordon.

“As sure as Kilimanjaro rises like Olympus above the Serengeti,” sings Toto in Africa. Last I looked, Kilimanjaro was in Tanzania, 200 miles from the Serengeti. Olympus is in Greece. Why not “As sure as the Eiffel Tower rises above the Outback”? The lyricist admitted he wrote it based on National Geographic photos. Translation: “I’m paid to look at pictures, not read the captions.”

“Plasticine porters with looking glass ties,” wrote John Lennon in Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds. Plasticine must have sounded to John like some high-gloss super-polymer. But as the 1960s English-speaking world knew, Plasticine is a children’s modeling clay. Were these porters melting in the sun? No other psychedelic substances available that day? The smell of kindergarten fails to transport me into Lennon’s hallucinatory dream world.

And finally, Take Me Home, Country Roads. This one I take personally. John Denver, already richer than God, sat down to write a love letter to West Virginia and somehow imported the Blue Ridge Mountains and Shenandoah River from Virginia. Maybe he looked at an atlas once, diagonally. The border between WV and VA is admittedly jagged, but at least try to feign some domain knowledge. Apologists say he meant blue-ridged mountains or west(ern) Virginia – which only makes it worse. The song should have been called Almost Geographically Adjacent to Heaven.

Precision may not make art, but art that ignores precision is just noise with a budget. I don’t need perfection – only coherence, proportion, and the occasional working map. I’m not obsessive. I just want a world where the train on the wall doesn’t leave the station half a century early. I’ve learned to live among the lax, even as they do it all wrong.

The Comet, the Clipboard, and the Knife

Posted in Commentary on October 2, 2025

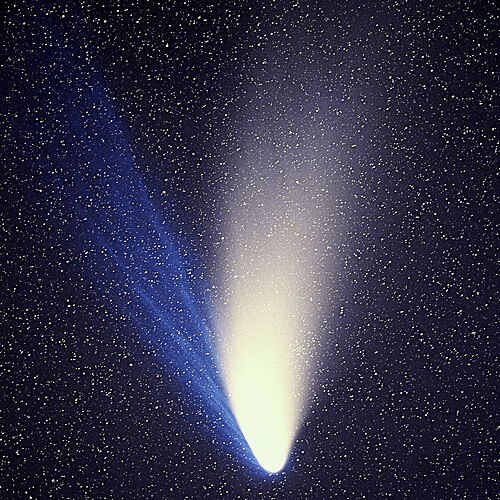

Background: My grandfather saw Comet Halley in 1910, and it was the biggest deal since the Grover Cleveland inaugural bash. We discussed it – the comet, not the inaugural – often in my grade school years. He told me of “comet pills” and kooks who killed themselves fearing cyanogens. Halley would return in 1986, an unimaginably far off date. Then out of nowhere in 1973, Luboš Kohoutek discovered a new comet, an invader from the distant Oort cloud – the flyover states of our solar system – and it was predicted to be the comet of the century. But Comet Kohoutek partied too hard somewhere near Saturn and arrived hungover, barely visible. And when Halley finally neared the sun in 1986, the earth was 180 degrees from it. Halley, like Kohoutek, was a flop. But 1996 brought Comet Hale-Bopp. Now, that was a sight even for urban stargazers. I saw it from Faneuil Hall in Boston and then bright above the Bay Bridge in San Francisco. It hung around for a year, its dual tails unforgettable. And as with anything cool, zealots stained its memory by freaking out.

A Sermon by Reverend Willie Storage, Minister of Peculiar Gospel

Brethren, we take our text today from The Book of Cybele, Chapter Knife, Verse Twenty-Three: “And lo, they danced in the street, and cut themselves, and called it joy, and their blood was upon their sandals, and the crowd applauded and took up the practice, for the crowd cannot resist a parade.”

To that we add The Epistle of Origen to the Scissors, Chapter Three, Verse Nine: “If thy member offend thee, clip it off, and if thy reason offend thee, chop that too, for what remains shall be called purity.”

These ancient admonitions are the ancestors of our story today, which begins not in Alexandria, nor the temples of Asia Minor, nor the starving castles of Languedoc, but in California, that golden land where individuality is a brand, rebellion is a style guide, and conformity is called freedom. Once it was Jesus on the clouds, then the Virgin in the sun, then a spaceship hiding behind a comet’s tail.

Thus have the ages spoken, and thus, too, spoke California in the year of our comet, 1997, when Hale-Bopp streaked across the sky like a match-head struck on the dark roof of the world. In Iowa, folk looked up and said, “Well, I’ll be damned – pass the biscuits.” In California, they looked up and said, “It conceals a spaceship,” and thirty-nine of them set their affairs in order, cut their hair to regulation style and length, pulled on black uniforms, laced up their sneakers, “prepared their vehicles for the Great Next Level,” and died at their own hands.

Now, California is the only place on God’s earth where a man can be praised for “finding himself” by joining a committee, and then be congratulated for the originality and bravery of this act. It is the land of artisan individuality in bulk: rows of identically unique coffee shops, each an altar to self-expression with the same distressed wood and imitation Edison bulbs. Rows of identically visionary cults, each one promising your personal path to the universal Next Level. Heaven’s Gate was not a freak accident of California. It was California poured into Grande-size cups and called “Enlightenment.”

Their leader, Do – once called Marshall Applewhite or something similarly Texan – explained that a spacecraft followed the comet, hiding like a pea under a mattress, ready to transport them to salvation. His co-founder, Ti, had died of cancer, inconveniently, but Do explained it in terms Homer Simpson could grasp: Ti had merely “shed her vehicle.” More like a Hertz than a hearse, and the rental period of his faithful approached its earthly terminus. His flock caught every subtle allusion. Thus did they gather, not as wild-eyed fanatics, but as the most polite of martyrs.

The priests of Cybele danced and bled. Origen of Alexandria may have cut himself off in private, so to speak, as Eusebius explains it. The Cathars starved politely in Languedoc. And the Californians, chased by their own doctrine into a corner of Rancho Santa Fe creativity, bought barbiturates at a neighborhood pharmacy, added a vodka chaser, then followed a color-coded procedure and lay down in rows like corn in a field. Their sacrament was order, procedure, and videotaped cheer. Californians, after all, enjoy their own performances.

Even the ancients were sometimes similarly inclined. Behold a relief from Ostia Antica of a stern priest nimbly handling an egg – proof, some claim, that men have long been anxious about inconvenient appendages, and that Easter’s chocolate bounty has more in common with the castrated ambitions of holy men than with springtime joy. Emperor Claudius, more clever than most, outlawed such celebrations – or tried to.

Brethren, it is not only the comet that inspires folly. Consider Sherry Shriner – a Kent State graduate of journalism and political science – who rose on the Internet just this century, a prophet armed with a megaphone, announcing that alien royalty, shadowy cabals, and cosmic paperwork dictated human destiny, and that obedience was the only path to salvation. She is a recent echo of Applewhite, of Origen, of priests of Cybele, proving that the human appetite for secret knowledge, cosmic favor, and procedural holiness only grows with new technology. Witness online alien reptile doomsday cults.

Now, California is a peculiar land which – to paraphrase Brother Richard Brautigan – draws Kent State grads like a giant Taj Mahal in the shape of a parking meter. Only there could originality be mass-produced in identical black uniforms, only there could a suicide cult be entirely standardized, only there could obedience to paperwork masquerade as freedom. The Heaven’s Gate crowd prized individuality with the same rigor that the Froot Loops factory prizes the relationship between each loop piece’s color and its flavor. And yet, in this implausible perfection, we glimpse an eternal truth: the human animal will organize itself into committees, assign heavenly responsibilities, and file for its own departure from the body with the same diligence it reserves for parking tickets.

And mark these words, it’s not finished. If the right comet comes again, some new flock will follow it, tidy as ever, clipboard in hand. Perhaps it won’t be a flying saucer but a carbon-neutral ark. Perhaps it will be the end of meat, of plastic, of children. You may call it Extinction Rebellion or Climate Redemption or Earth’s Last Stand. They may chain themselves to the rails and glue themselves to Botticelli or to Newbury Street, fast themselves to death for Mother Goddess Earth. It is a priest of Cybele in Converse high tops.

“And the children of the Earth arose, and they glued themselves to the paintings, and they starved themselves in the streets, saying, ‘We do this that life may continue.’ And a prophet among them said, ‘To save life ye must first abandon it.’”

If you must mutilate something, mutilate your credulity. Cut it down to size. Castrate your certainty. Starve your impulse to join the parade. The body may be foolish, but it has not yet led you into as much trouble as the mind.

Sing it, children.

—

Cave Bolts – 3/8″ or 8mm? – Or Wrong Question?

Posted in Engineering & Applied Physics on September 2, 2025

Three eighths inch bolts – or 8mm? You’ll hear this debate as you drift off to sleep at the Old Timers Reunion. Peter Zabrok laughs it off: quarter inch, he says, for climbing. Sure, on El Capitan, where Pete hangs out, quarter inch is justifiable – clean granite, smooth walls, long pitches. But caves – water-carved knife edges, mud, rock of wildly varying strength, and the chance of being skewered on jagged breakdown – give rise to a different calculus of bolt selection.

It’s easy to look up manufacturers’ data and see that 8mm is “super good enough.” The phrase comes from a YouTube channel that teaches– perhaps inadvertently – that ultimate strength is all that matters. I’m cursed with a background in fasteners. I’ve looked at too many failed bolts under scanning electron microscopes. I’ve been an expert witness in cases where bolts took down airplanes and killed people. From that perspective, ultimate breaking strength is a lousy measure of gear. Let’s reframe the 3/8 vs 8mm (M8) diameter question with an engineer’s eye – and then look at bolt length.

The Basics without the Fetish

Let’s keep this down to earth. I’ll mostly use English units – pounds and inches. Most cavers I know can picture 165 pounds but have no feel for a kilonewton. Physics should be relatable, not a fetish. Note: 8mm is close to 5/16 inch (0.314 vs 0.3125), but don’t mix metric drills with imperial bolts.

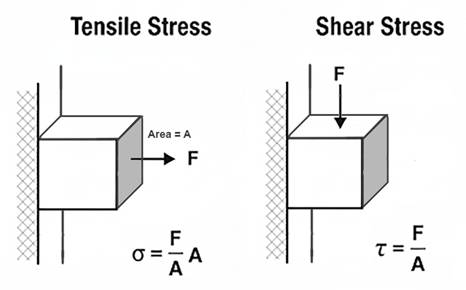

Stress = force ÷ area. Pull 10 pounds on a one-square-inch rod, you get 10 psi. Pull 100 pounds on ten square inches, you also get 10 psi. This is an example of tensile stress.

Shear stress is the sideways cousin – one part of a bolt sliding past the other, as when a hanger tries to cut it in half, to cut (shear) the bolt across its cross-section.

Ultimate stress (ultimate strength) is the max before breakage. Yield stress (yield strength) is the point where a bolt stops bouncing back and bends or stretches permanently. For metals, engineers define yield strength as 0.2% permanent deformation. Ratios of yield-to-ultimate vary wildly between alloys, which matters in picking metals. Note here that “strength” refers to an amount in pounds (or newtons) when applied to a part like a bolt but to an amount in pounds per square inch (or pascals) when applied to the material the part is made from.

Bolts in Theory, Bolts in Caves

The strength of wedge anchor made of 304 stainless depends on 304’s ultimate tensile strength (UTS) and the effective stress area of the bolt’s threaded region. Standard numbers: UTS ≈ 515 MPa (75,000 psi). For an M8 coarse bolt, tensile area = 36.6 mm². For a 3/8-16 UNC, it’s 50 mm².

As detailed elsewhere, a properly installed (properly torqued) bolt is not loaded in shear, regardless of the bolt orientation (vertical or horizontal) or the load application direction (any combination of vertical or sideways). But most bolts installed in caves are not properly installed. So we’ll assume that vertical bolts are properly torqued (otherwise they would fall out) and that horizontal bolts are untorqued. In such cases, horizontal bolts are in fact loaded in shear; the hanger bears directly on the bolt.

We can first look at the tension case – a wedge anchor in the ceiling; you hang from it. The axial (tensile) strength is calculated as UTS × A. This formula falls out of the definition of tensile stress: σ = F / A_t, where F is the axial force and A_t is the effective area over which the tensile stress acts. Shear stress (conventionally denoted τ where tensile stress is denoted σ) is defined as τ = F / A_s, where A_s is the area over which the shear stress acts.

In a bolt, A_t and A_s would seem to be identical. In fact, they are slightly different because the shear plane often passes through the threaded section at a slight angle from the tensile plane, thereby reducing the effective area. More importantly, ductile materials like 304 stainless steel undergo plastic deformation at the microscopic scale in a way that renders the basic theoretical formula (τ = F / A_s) less applicable. In this situation, the von Mises yield criterion (aka distortion energy theory) is typically used to predict failure under combined stresses. This criterion relates shear ultimate strength to tensile yield strength. The maximum shear stress a material can withstand (τ_max) is approximately equal to σ_yield / √3 × σ_yield. For predicting ultimate shear strength (USS), theory and empirical test data show that bolts made of ductile metals like mild carbon steel or 304 stainless have ultimate shear strength that is about 0.6 × their ultimate tensile strength.

The tensile stress area (A_s) for an M8 coarse thread bolt is 36.6 mm² (0.057 in²). For a 3/8-16 UNC bolt, A_s is 50 mm² (0.078 in²).

Simple math says:

| Diameter | Tensile Stress Area | Axial Strength | Shear Strength |

| M8 | 36.6 mm² | 4,236 lb | 2,542 lb |

| 3/8 inch | 50 mm² | 5,798 lb | 3,479 lb |

The 3/8 inch bolt has 37% higher tensile and shear strength than the M8 bolt, due to its larger effective cross-section. These values are ultimate strengths of the bolts themselves. Actual load capacities (strengths) of the anchor placement might be lower – if a hanger breaks, if the rock breaks (a cone of rock pulls away), or if the bolt pulls out (the rock yields where the bolt’s collar presses into it).

For reasons cited above (von Mises etc.), the shear strength of each bolt size is less than its tensile strength. For the 8mm bolt, is 2500 pounds (11 kn) strong enough? That’s about a factor of 14 greater than the weight of a 180 pound (80 kg) caver. That’s 14 Gs, which is about the maximum force that humans survive in harnesses designed to prevent a person’s back from bending backward – lumbar hyperextension. Caving harnesses, because of the constraints of single rope technique (SRT), do not supply this sort of back protection. Five to eight Gs is often cited as a likely maximum for survivability in a caving harness.

So 2500 pounds of shear strength seems strong enough, though possibly not super strong enough, whatever that might mean. Is the ratio of bolt strength to working load big enough? The ratio of survivable load to bolt strength? How might a person expecting to experience only the force of his body weight suddenly experience 5Gs?

The UIAA (International Climbing and Mountaineering Federation) sets a maximum allowable impact force for ropes at 12 kN (2700 lb) for a single rope, which means roughly 6-9 Gs for an average climber (75 kg, 165 lb.)

When a bolt is preloaded (tightened to a specified torque, often approaching its yield strength), it induces a compressive force in the clamped materials (the hanger, washer, and the rock) and a tensile stress of equal magnitude in the bolt. For a preloaded bolt, an externally applied load does not increase the tensile stress in the bolt until the external load approaches the preload force. This is because the external load first reduces the compressive force in the clamped materials rather than adding to the bolt’s tension. This behavior is well-documented in bolted joint mechanics (e.g., Shigley’s Mechanical Engineering Design).

For loads perpendicular to the bolt axis, preload can significantly enhance the bolted joint’s shear capacity. The improvement comes from the frictional resistance generated between the clamped surfaces (e.g., the hanger and concrete) due to the preload-induced compressive force. This friction can resist shear loads before the bolt itself is subjected to shear stress.

Basing preload on the yield strength of the bolts’ 304 stainless material (215 MPa, 31,200 psi) and the cross-sectional area of the threads used above gives the following preload forces:

M8 bolt preload: 215 MPa × 36.6 mm² ≈ 7,869 N (1,767 lb).

3/8 inch bolt preload: 215 MPa × 50 mm² ≈ 10,750 N (2,413 lb).

If we assume a coefficient of friction of 0.4 between hanger and bedrock, we can calculate the frictional forces perpendicular to horizontally placed bolts. These frictional forces can fully resist perpendicular (vertical) loads up to a limit of μ × preload (where μ is the friction coefficient and F_friction = μ × F_preload). For μ = 0.4, the shear resistance from friction alone could be:

M8: 0.4 × 7,869 N ≈ 3,148 N (707 lb).

3/8 inch: 0.4 × 10,750 N ≈ 4,300 N (966 lb).

These frictional capacities are substantial, meaning the bolt’s shear strength becomes relevant only if the frictional capacity is exceeded. The preload is highly desirable, because it prevents the rock and the bolt from “feeling” the applied load, and therefore prevents any cyclic loading of the bolt, even when cyclic loads are applied to the joint (via the hanger).

However, the frictional capacity (707 lb for M8) usually does not add to the shear capacity of the bolt, once preload is exceeded. Its shear capacity remains at 2542 lb as calculated above, because once the hanger slips relative to the rock, the bolt itself begins to bear the shear load directly.

Now, with properly torqued, preloaded bolts, we can return to the main question: are M8 bolts “good enough”? Two categories of usage come to mind – aid climbing and permanent rigging. Let’s examine each, being slightly conservative. For example, we’ll assume no traction or embedding of the hanger, something that often but not always exists, which results in an effective coefficient of friction between rock and hanger of 1.0 or more. We’ll use 8Gs as a threshold of survivability and 0.4 as a coefficient of friction – though friction becomes mostly irrelevant in this worst-case analysis.

Comparative Analysis – 3/8 vs M8 (first order approximations)

For an M8 bolt, preload near yield (215 MPa × 36.6 mm² = 7.9 kN / 1,767 lb) gives a frictional capacity of 0.4 × 7.9 kN = 3.16 kN (707 lb).

For a 3/8 inch bolt (215 MPa × 50 mm² = 10.8 kN / 2,413 lb), it’s 0.4 × 10.8 kN = 4.3 kN (966 lb).

The 8 G threshold (80 kg climber, 8 × 785 N = 6.3 kN / 1,412 lb) exceeds both frictional capacities, meaning the joint slips, and the bolt bears shear stress in these high-load cases, regardless of torquing.

Once friction is exceeded, the bolt’s shear strength governs: 11.3 kN (2,542 lb) for 8mm, 15.5 kN (3,479 lb) for 3/8 inch (based on 0.6 × UTS = 309 MPa).

Both M8 and 3/8 exceed 6.3 kN, confirming that the analysis hinges on shear strength, not friction, for high-load cases. Torquing is critical to achieve the assumed preload (near yield) and to confirm placement quality (a torqued bolt indicates a successful installation). However, in high-load cases (≥6.3 kN), the frictional capacity is irrelevant once exceeded, and the analysis stands on the bolt’s shear strength and the rock integrity.

Since high-load cases (e.g., 8 G = 6.3 kN) exceed the frictional capacity of both bolt diameters (3.16 kN for 8mm, 4.3 kN for 3/8 inch), the decision rests on shear strength margin:

M8: 11.3 kN (2,542 lb) provides a ~1.8x factor of safety (see note at bottom on factors of safety) over 6.3 kN.

3/8 inch: 15.5 kN (3,479 lb) offers a ~2.5x factor, ~37% higher, giving more buffer against rock variability or slight overloads.

In some limestone (10–100 MPa), the rock will fail (e.g., pullout) well below the bolt’s shear strength. Remember that with torqued bolts the rock does not “feel” any load until the axial load exceeds preload or the perpendicular load exceeds the friction force generated by the preload. But in softer (low compressive strength) limestone, once those thresholds are exceeded, the rock often fails before the bolt fails in shear or tension. 3/8 inch’s larger diameter distributes load better, reducing rock stress (bearing stress = force / diameter × embedment).

Most of us use redundant anchors for permanent rigging, and you should too. A dual-anchor system with partial equalization (double figure eight, bunny-loop-knot, 1–3 inch drop limit) ensures no single failure is catastrophic. A 3-inch drop would add ~1 kN to the force felt by the surviving anchor. This is within the backup bolt’s shear capacity, making 8mm viable.

What about practical factors? M8 bolts save ~20–35% battery life and weight, critical for remote locations. M8 does not align with ASC/UIAA standards (≥3/8 inch preferred). 3/8 is obviously better for permanent anchors in marginal rock, not because the bolt is stronger, but because the contact stresses are about 35% lower – a potentially significant difference.

Effect of Bolt Length on Anchor Failure in Limestone

In typical installations of wedge bolts in limestone, axial (tensile) loading, steel failure often governs (e.g., the bolt fractures at the threads), while in shear loading, the anchor typically experiences partial pullout with bending, followed by a cone-shaped rock breakout (pry-out failure). This is consistent with industrial experience in concrete, where tensile failures are steel-dominated due to the anchor’s expansion mechanism providing sufficient grip, but shear failures involve pry-out because the load induces bending and leverages the embedment. The collar (sleeve, expansion clip) in most brands is identical for all bolt lengths of a given diameter. The gripping mechanism doesn’t change with length. The primary difference is the effective embedment depth (h_ef), which affects load distribution in the rock. Longer bolts increase the volume of rock engaged and better resistance to breakout, but this benefit is more pronounced in shear than tension, as preload clamping compresses a larger rock section under the hanger, distributing stresses and reducing localized crushing.

To estimate failure loads for 2.5 inch vs. 3.5 inch total lengths, we can use standard engineering formulas adapted from ACI 318* (* I won’t violate copyright by linking to outlaw PDFs, but I think standards bodies that sell specs for hundreds of dollars do the world a huge injustice) for post-installed wedge anchors, treating limestone as analogous to concrete, with adjustments for its variable strength.

The compressive strength of limestone (f_c’) varies from 1,000 psi (soft, e.g., oolitic limestone) to 10,000 psi (harder types). We’ll use 4,000 psi (27.6 MPa) based on typical Appalachian limestone values. For stronger (compressive strength) limestone (e.g., 8,000 psi / 55 MPa), capacities increase by1.4x (proportional to the square root of f_c’).

Embedment Depth (h_ef) is the bolt length minus hanger thickness (~0.25 inch) and nut/washer (~0.375 inch). Thus, h_ef ≈ 1.875 inches for 2.5 inch bolt; h_ef ≈ 2.875 inches for 3.5 inch bolt. This assumes that a “good” hole has been drilled, allowing the collar to catch immediately as the bolt is torqued.

We’ll assume 304 stainless, ultimate tensile ~5,798 lb (25.8 kN), ultimate shear ~3,479 lb (15.5 kN), as previously calculated. 316 alloy would give similar results. We’ll assume proper torquing for preload and no edge effects, meaning the bolt is at least 10 bolt-diameters from edges and cracks.

Formulas (ACI-based, ultimate loads):

- Tensile Rock Breakout: N_cb ≈ 17 × √f_c’ × h_ef^{1.5} lb (k_c=17 for post-installed in cracked conditions; use for conservatism; f_c’ in psi, h_ef in inches).

- Axial Failure Load: Min(N_cb, steel tensile).

- Shear Pry-Out: V_cp ≈ k_cp × N_cb (k_cp=1 for h_ef < 2.5 inches; k_cp=2 for h_ef ≥ 2.5 inches, reflecting increased resistance to rotation).

- Shear Failure Load: Min(V_cp, steel shear), but with bending preceding rock failure.

- Capacities are ultimate (failure); apply safety factors (e.g., 4:1 per UIAA) for working loads.

With these formulas we can compare different bolt lengths in axial loading. Longer bolts increase h_ef, enlarging the breakout cone and distributing tensile stresses over greater rock volume. Preload clamping compresses the rock under the hanger (area ~0.5-1 in² depending on washer diameter), and longer bolts may slightly reduce localized stress concentrations at the surface due to better load transfer deeper in the hole. If rock breakout capacity exceeds steel strength, the bolt fractures. In weaker limestone, rock governs; in harder, steel does. The identical sleeve means expansion grip is consistent, so length primarily affects rock engagement.

So for 4000 psi limestone and 3/8 bolts in tension, axially loaded, we get:

2.5 inch (h_ef ≈ 1.875 in): N_cb ≈ 17 × 63.25 × (1.875)^{1.5} ≈ 2,765 lb (12.3 kN). Rock breakout governs (cone failure).

3.5 inch (h_ef ≈ 2.875 in): N_cb ≈ 17 × 63.25 × (2.875)^{1.5} ≈ 5,240 lb (23.3 kN). Rock breakout governs (cone-pullout).

For M8 bolts, axially loaded (2.5 in. ≈ 64mm, 3.5 in ≈ 90mm):

2.5 inch (h_ef ≈ 1.875 in): N_cb ≈ 17 × √4,000 × (1.875)^{1.5} ≈ 17 × 63.25 × 2.576 ≈ 2,765 lb (12.3 kN). Steel tensile = 4,236 lb (18.8 kN). Rock breakout governs (cone failure).

3.5 inch (h_ef ≈ 2.875 in): N_cb ≈ 17 × 63.25 × (2.875)^{1.5} ≈ 17 × 63.25 × 4.873 ≈ 5,240 lb (23.3 kN). Steel tensile = 4,236 lb (18.8 kN). Steel fracture governs (bolt breaks at threads, matching test observations).

2,765 lb (for both 3/8 and M8 bolts), particularly in redundant anchors, seems reasonable, based on the limits of human survivability and on the other gear in the chain. Nevertheless, this result surprised me. One-inch greater length doubles the effective anchor strength for axial loads.

When a shear load is large enough to exceed bolt preload (which should never happen with actual working loads), the shear force induces bending (lever arm from hanger to expansion point) and pry-out, where the bolt rotates, pulling out the back side and causing a cone breakout. Longer bolts increase h_ef, enhancing pry-out resistance by engaging more rock mass and distributing compressive stresses. If pry-out exceeds steel shear capacity, the bolt bends and shears. Industrial studies show embedment beyond 10x diameter (3.75 inches for 3/8 inch, 80mm for M8 bolts) adds minimal shear benefit.

For 4,000 psi limestone and 3/8 bolts with tensile loads:

2.5 inch (h_ef ≈ 1.875 in < 2.5 in): V_cp ≈ 1 × 2,765 lb ≈ 2,765 lb (12.3 kN). Rock pry-out governs (partial pullout, bending, then cone breakout).

3.5 inch (h_ef ≈ 2.875 in > 2.5 in): V_cp ≈ 2 × 5,240 lb ≈ 10,480 lb (46.6 kN) > steel shear → Steel governs (~3,479 lb [15.5 kN], with bending preceding shear failure).

For stronger limestone (8,000 psi compressive), 3/8 bolt capacities are ~1.4x higher (e.g., 3,870 lb for 2.5 in pry-out; steel 3,479 lb for 3.5 in), emphasizing length’s role in shifting from rock to steel failure.

For 4,000 psi limestone and M8 bolts with shear loads:

2.5 inch (h_ef ≈ 1.875 in < 2.5 in): V_cp ≈ 1 × 2,765 lb ≈ 2,765 lb (12.3 kN). Steel shear = 2,542 lb (11.3 kN). Steel shear governs (barely – bolt bends, then shears, with partial pullout).

3.5 inch (h_ef ≈ 2.875 in > 2.5 in): V_cp ≈ 2 × 5,240 lb ≈ 10,480 lb (46.6 kN). Steel shear = 2,542 lb (11.3 kN). Steel shear governs (bolt bends/shears before rock pry-out).

For harder limestone (8,000 psi), M8/8 bolt capacities are ~1.4x higher, again emphasizing length’s role in shifting from rock to steel failure.

2.5 inch: V_cp ≈ 1 × 3,870 lb ≈ 3,870 lb (17.2 kN). Steel = 2,542 lb. Steel shear governs.

3.5 inch: V_cp ≈ 2 × 7,340 lb ≈ 14,680 lb (65.3 kN). Steel = 2,542 lb. Steel shear governs.

Summary – Failure Loads in 1,000, 4,000, and 8,000 psi Limestone

([S] indicates steel failure, [R] indicates rock failure. Loads given in pounds and (kilonewtons):

| Bolt Size | 2.5 in Axial | 2.5 in Shear | 3.5 in Axial | 3.5 in Shear |

| 1000 psi limestone | ||||

| M8 (8mm) | 1,382 (6.15) [R] | 1,382 (6.15) [R] | 2,620 (11.7) [R] | 2,542 (11.3) [S] |

| 3/8 inch | 1,382 (6.15) [R] | 1,382 (6.15) [R] | 2,620 (11.7) [R] | 2,620 (11.7) [R] |

| 4000 psi limestone | ||||

| M8 (8mm) | 2,765 (12.3) [R] | 2,542 (11.3) [S] | 4,236 (18.8) [S] | 2,542 (11.3) [S] |

| 3/8 inch | 2,765 (12.3) [R] | 2,765 (12.3) [R] | 5,240 (23.3) [R] | 3,479 (15.5) [S] |

| 8000 psi limestone | ||||

| M8 (8mm) | 3,870 (17.2) [R] | 2,542 (11.3) [S] | 4,236 (18.8) [S] | 2,542 (11.3) [S] |

| 3/8 inch | 3,870 (17.2) [R] | 3,870 (17.2) [R] | 5,798 (25.8) [S] | 3,479 (15.5) [S] |

Bottom Line

For me, the key insight is that shear pry-out capacity in limestone anchors scales significantly with embedment depth. Extending bolt length from 2.5 to 3.5 inches increases pry-out resistance by approximately 100–200%, driven by the deeper rock engagement and the ACI 318 k_cp factor (1 for h_ef < 2.5 inches, 2 for h_ef ≥ 2.5 inches), though it’s ultimately capped by the bolt’s steel shear strength (2,542 lb / 11.3 kN for 8mm, 3,479 lb / 15.5 kN for 3/8 inch). When rock strength governs failure, as it often does in weaker (compressive strength) limestone (e.g., 1,000–4,000 psi), 3/8 inch bolts offer no advantage over 8mm (M8), as both have identical rock-limited capacities (e.g., 1,382 lb in 1,000 psi, 2,765 lb in 4,000 psi at 2.5 inches). Thus, choosing a 3.5 inch bolt over a 2.5 inch bolt is typically more critical than choosing between 3/8 inch and 8mm diameters.

Most bolts, particularly wall anchors in aid climbing or permanent setups, experience perpendicular loads. These are initially resisted by friction from tensile preload (e.g., 707 lb for 8mm, 966 lb for 3/8 inch with μ = 0.4), but when loads exceed this – as in a severe 8 G fall (1,412 lb / 6.3 kN for an 80 kg climber) – shear stress initiates. In caves I visit, permanent anchors are redundant, using dual bolts with crude equalization to limit drops to 1–3 inches, ensuring no single failure is catastrophic. In aid climbing, dynamic belays and climbing methodology/technique reduce criticality of single bolt failures. While 3/8 inch bolts provide ~37% higher steel strength (e.g., 3,479 lb vs. 2,542 lb shear), this margin is not a significant safety improvement in an engineering analysis, given typical climber weights (80–100 kg) and redundant anchor systems. Few people use stainless for aid climbs, but the numbers above still roughly apply for mild-steel bolts. In weak limestone (1,000 psi), rock failure governs at low capacities (e.g., 1,382 lb), making length critical and diameter secondary. In harder limestone (8,000 psi), 3/8 inch offers a slight edge, but redundancy and proper placement outweigh diameter differences. For engineering analysis, you can substitute 5/16 inch bolts for M8 in the above; just don’t mix components from each.

25-28 ft-lb seems a good torque for preloading 3/8-16 304 bolts and is consistent with manufacturers’ dry-torque recommendations. For 8mm and 5/16-18 304 bolts, manufacturers’ recommendations range from 11 (Fastenal, Engineer’s Edge, Bolt Depot) to 18 ft-lb (Allied Bolt Inc). For 304 SS (yield ~32 ksi), the tensile stress area of a 5/16-18 bolt is ~0.0524 in², so yield preload is about 1650 pounds. Most manufacturers seem a bit conservative on torque recommendations, likely because construction workers sometimes tend to overtorque. Using T = K × D × P (K ~0.2–0.35 dry for SS, D = 0.3125 in), 11 ft-lb, we get ~1,000–1,900 lb preload (below yield), while 18 ft-lb corresponds to ~1,700–3,100 lb. of preload. The latter is above yield for standard 304 stainless; Allied Bolt’s hardware appears to be a high-yield variant (ASTM F593-24) of 304. 304 can be cold-worked to achieve yield strengths above 70,000 psi. I’m using 32,000 psi for these calculations, so I’ll aim for 11-12 ft-lb of torque underground.

“Factor of Safety” Is a Crutch

We throw around “factor of safety.” It’s a crude ratio of strength to expected load. For example, M8 shear = 11.3 kN vs. 6.3 kN load → 1.8x. But that’s a false comfort. Real engineering moved past simple safety factors decades ago. Load and resistance factors, environment, materials, inspection – all matter more.

In the era of steam trains, designers would calculate the required cross section of a bolt based on design loads, and then “slap on a 3X” (factor of safety) and be done with it. The world then moved to limit-state design, damage tolerance, environment-specific factors, inspection and maintenance schedules, and probabilistic risk assessment. As a design philosophy, factor of safety is dead. As a bureaucratic metric for certification, even sometimes in aerospace, it persists.

The factor of safety, expressed as a ratio (e.g., 1.8 for an 8mm bolt’s shear strength of 11.3 kN over a 6.3 kN load), implies a simple buffer against failure. This can foster a false sense of security among non-technical users, suggesting that a bolt is “safe” as long as the ratio is greater than 1 (or pick a number). In reality, the concept oversimplifies the complexities of anchor performance in real-world conditions.

Factor of safety tends to roll up all sorts of unrelated ways that a piece of equipment or its placement might, in practice, not live up to its theory. It groups all the ways a part might degrade in use together – and groups all the ways any part in your hand might differ from the one(s) that got tested. In short, it is an overly sloppy concept that plays little part in the design of serious gear. Some parts don’t wear. Some manufacturing processes render every specimen of equal size, strength, and surface finish to a fraction of a percent. Some materials corrode like hell. Environments matter. Limestone compressive strength can range from 1 to 100 MPa in the same geologic formation. A poor placement with no preload can leave a 3 inch bolt that can be pulled out when the climber leaned back on it. Not an exaggeration; I have seen this happen – and saw the belayer, Andrea Futrell, go skidding six feet across the floor as a result. Never raised her voice. Dynamic belay par excellence.

Overemphasizing factor of safety can lead to dangerous assumptions, such as trusting a single anchor without redundancy, regardless of its size (do we really need more half inch bolts rusting away atop big drops), or neglecting regular gear inspection. For bolt placement, prudence and sanity insist that no single failure can be catastrophic. As is apparent from the above, proper torquing of bolts removes a great deal of unknowns from the equation.

I stress that “factor of safety” is a crude talking point that often reveals a poor understanding of engineering. So let’s be clear: survivable caving isn’t about safety factors. It’s about redundancy, placement, inspection, and understanding your rock.

That’s how you prevent overconfidence – and make informed decisions about stuff that will kill you if you screw up.

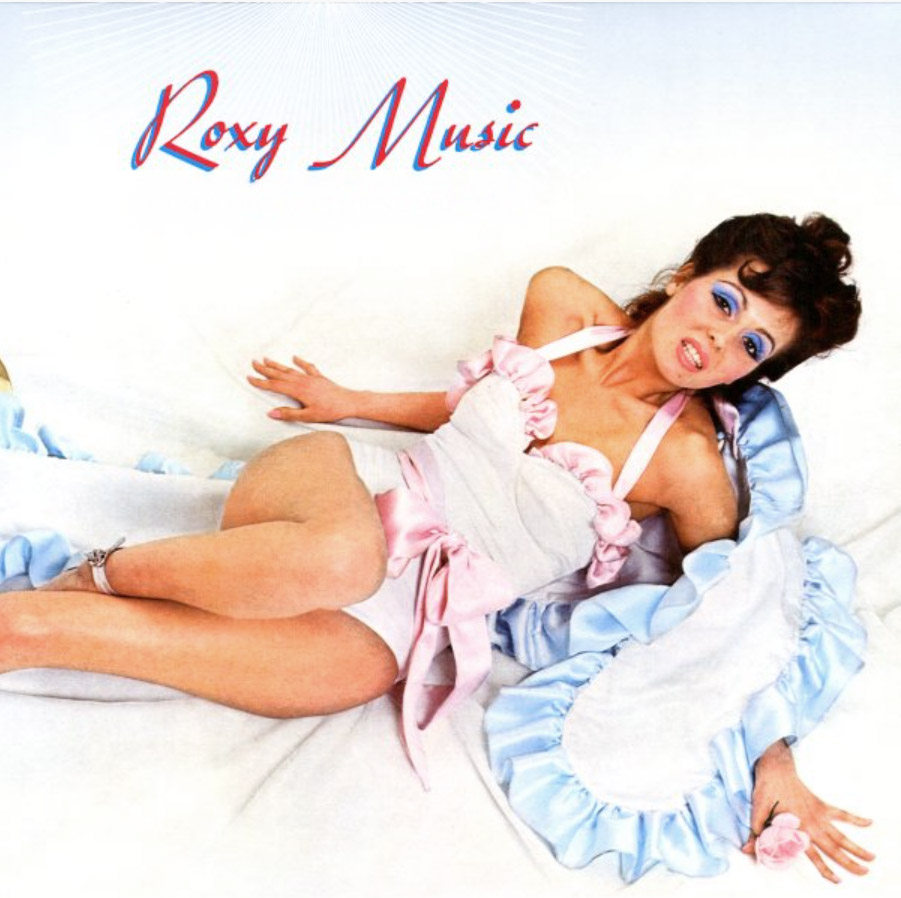

Roxy Music and Forgotten Social Borders

Posted in History of Art on August 20, 2025

In the early 1970s rock culture was diverse, clannish and fiercely territorial. Musical taste usually carried with it an entire identity, including hair length and style, clothing – including shoes/boots – politics, and which record stores you could haunt. King Crimson, Yes, Pink Floyd, and Emerson, Lake & Palmer belonged to the progressive end of the spectrum.

By the early 1970s, progressive rock (prog, as shorthand began to appear in music press) was musical descriptor and social signal. Calling a band “progressive” implied a certain seriousness, technical sophistication, and intellectual ambition. It marked a listener as someone who prized virtuosity, complexity, and concept albums over pop singles. The label carried subtle class and educational connotations: prog fans were expected to appreciate classical references, odd time signatures, extended solos, and experimental studio techniques. King Crimson was often called avant-garde rock, though Henry Cow deserved the label much more. ELP was called symphonic rock, Pink Floyd was psychedelic rock, and Yes was Epic rock – but they were all prog. And listening to all this stuff made you smart. Or pretentious.

Across the divide, the early 70s saw greaser rock and the emerging ’50s nostalgia circuit. Sha Na Na, the sock-hop revival, the idea that a gold lamé suit was a passport to a simpler age ushered in the Happy Days craze and its music. Few people straddled those camps. A Crimson devotee wouldn’t admit to liking Sha Na Na if he wanted to keep his dignity. Rock music was attitude, self-image, and worldview.

Into that landscape stepped Roxy Music in 1972, and they were utterly bewildering. Bryan Ferry came dressed like a lounge lizard from a time-warped jukebox, crooning with a sincerity that clearly wasn’t parody or caricature. Still, it was far too stylized to be mere mimicry. His band conjured a storm of dissonant non-keyboard electronics, angular rhythms, and Brian Eno’s futuristic treatments. Roxy Music embraced rather than mocked the early rock gestures of Elvis’s era. Ferry gave listeners permission to take Jerry Lee Lewis seriously, even reverently. Lewis was suddenly an avant-garde icon, pounding the keys with the same abandon that Eno applied to his electronics (witness Richard Trythall’s 1977 musique concrète: Omaggio a Jerry Lee Lewis).

That was the radicalism of early Roxy Music, which cannot be grasped retrospectively, even by the most avid young musicologist. Roxy dissolved the borders that the tribes of 1972 held sacred. They showed that ’50s rock, glam stylization, and avant-garde electronics could coexist in an unstable but persistent alloy. The shock of that is hard to grasp from today’s vantage point, when music is not tied to identity and “classic-rock” Roxy Music is remembered for Ferry’s Avalon-era suave crooning.

Oddly, and I think almost uniquely, as the band moved mainstream over the next fifteen years, the noisy, Eno-era chaos was retroactively smoothed into the same brand identity as Avalon. For later fans, there was no sharp rupture; the old chaos was domesticated and folded back into the same style sensibility.

But the rupture had existed. Their cover art reinforced it. Roxy Music (1972) with Kari-Ann Muller posing like a mid-century pin-up, was tame in skin exposure compared to H.R. Giger’s biomechanical nudity on ELP’s Brain Salad Surgery. The boldness of Roxy Music’s cover lay in context, not ribaldry. The sleeve was bluntly terrestrial. For a prog listener used to studying a Roger Dean landscape on a first listen of a new Yes album, Roxy Music surely seemed an insult to seriousness.

When Fleetwood Mac reinvented themselves in 1975, new listeners treated it as rebirth. The Peter Green blues band that authored Black Magic Woman and the Buckingham–Nicks hit machine lived in separate mental compartments. Very few Rumours-era fans felt obliged to revisit Then Play On or Kiln House, and most who did saw them as curiosities. Similarly, Genesis underwent a hard split. Its listeners did not treat Foxtrot and Invisible Touch as facets of a single project.

Roxy Music’s retrospective smoothing is almost unique in rock. Their chaos was polished backward into elegance. The Velvet Underground went the other way. At first their noise was cultish, even disposable. But as the legend of Reed, Cale, and Nico grew, the past was recoded as prophecy. White Light/White Heat became the seed of punk. The Velvet Underground & Nico turned into the Bible of indie rock. Even Loaded – a deliberate grab for radio play, stripped of abrasion – was absorbed into the myth and remembered as avant-garde. It wasn’t. But the halo of the band’s legend bled forward and made every gesture look radical.

Roxy Music remains an oddity. The suave Avalon listener in 1982 could put on Virginia Plain without embarrassment and believe that those early tracks were nearby on a continuum. Ferry’s suave sound bled backward and redefined the chaos. He retroactively re-coded the Eno-era racket. The radical rupture was smoothed out beneath the gloss of brand identity.

That’s why early Roxy is so hard to hear as it was first heard. In 1972 it was unclassifiable, a collision of tribes and eras. To grasp it, you have to forget everything that came after. Imagine a listener whose vinyl shelf ended with The Yes Album, Aqualung, Tarkus, Ash Ra Tempel, Curved Air, Meddle, Nursery Cryme, and Led Zeppelin IV. Sha Na Na was a trashy novelty act recycling respected antiques – Dion and the Belmonts, Ritchie Valens, Danny and the Juniors. Disco, punk, new wave? They didn’t exist.

Now, in that silence, sit back and spin up Ladytron.

“He Tied His Lace” – Rum, Grenades and Bayesian Reasoning in Peaky Blinders

Posted in Probability and Risk on August 4, 2025

“He tied his lace.” Spoken by a jittery subordinate halfway through a confrontation, the line turns a scene in Peaky Blinders from stylized gangster drama into a live demonstration of Bayesian belief update. The scene is a tightly written jewel of deadpan absurdity.

(The video clip and a script excerpt from Season 2, Episode 6 appears at the bottom of this article – rough language. “Peaky blinders,” for what its worth, refers to young brits in blindingly dapper duds and peaked caps in the 1920s.)

The setup: Alfie Solomons has temporarily switched his alliance from Tommy Shelby to Darby Sabini, a rival Italian gangster, in exchange for his bookies being allowed at the Epsom Races. Alfie then betrayed Tommy by setting up Tommy’s brother Arthur and having him arrested for murder. But Sabini broke his promise to Alfie, causing Alfie to seek a new deal with Tommy. Now Tommy offers 20% of his bookie business. Alfie wants 100%. In the ensuing disagreement, Alfie’s man Ollie threatens to shoot Tommy unless Alfie’s terms are met.

Tommy then offers up a preposterous threat. He claims to have planted a grenade and wired it to explode if he doesn’t walk out the door by 7pm. The lynchpin of this claim? That he bent down to tie his shoe on the way in, thereby concealing his planting the grenade among Alfie’s highly flammable bootleg rum kegs. Ollie falls apart when, during the negotiations, he recalls seeing Tommy tie his shoe on the way in. “He tied his lace,” he mutters frantically.

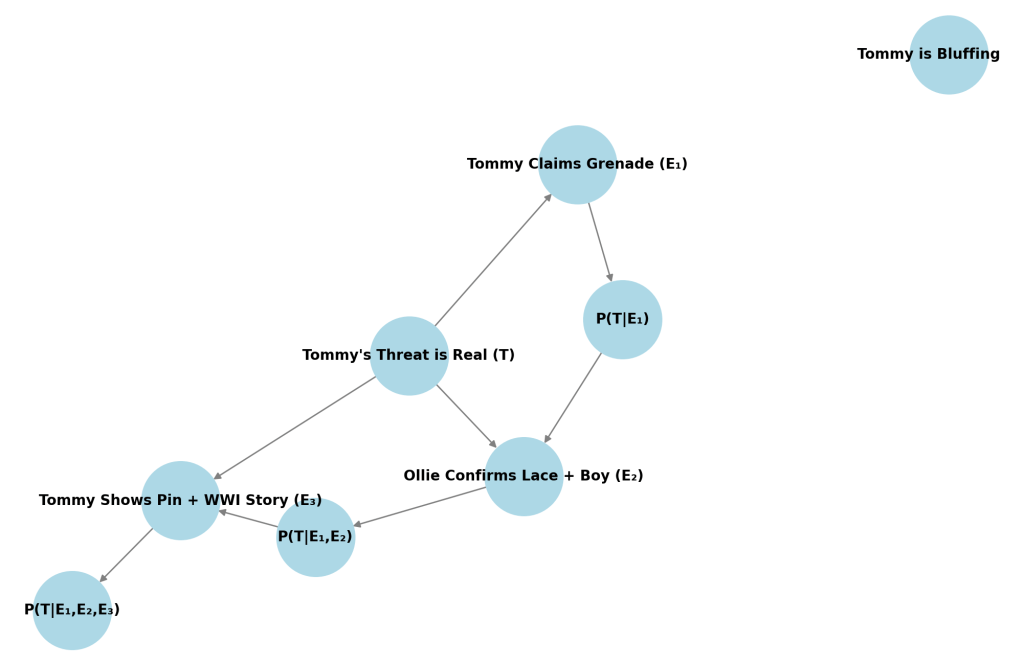

In another setting, this might be just a throwaway line. But here, it’s the final evidence given in a series of Bayesian belief updates – an ambiguous detail that forces a final shift in belief. This is classic Bayesian decision theory with sequential Bayesian inference, dynamic belief updates, and cost asymmetry. Agents updates their subjective probability (posterior) based on new evidence and choose an action to maximize expected utility.

By the end of the negotiation, Alfie’s offering a compromise. What changes is not the balance of lethality or legality, but this sequence of increasingly credible signals that Tommy might just carry through on the threat in response to Alfie’s demands.

As evidence accumulates – some verbal, some circumstantial – Alfie revises his belief, lowers his demands, and eventually accepts a deal that reflects the posterior probability that Tommy is telling the truth. It’s Bayesian updating with combustible rum, thick Cockney accents, and death threats delivered with stony precision.

Bayesian belief updating involves (see also *):

- Prior belief (P(H)): Initial credence in a hypothesis (e.g., “Tommy is bluffing”).

- Evidence (E): New information (e.g., a credible threat of violence, or a revealed inconsistency).

- Likelihood (P(E|H)): How likely the evidence is if the hypothesis is true.

- Posterior belief (P(H|E)): Updated belief in the hypothesis given the evidence.

In Peaky Blinders, the characters have beliefs about each other’s natures, e.g., ruthless, crazy, bluffing.

The Exchange as Bayesian Negotiation

Initial Offer – 20% (Tommy)

This reflects Tommy’s belief that Alfie will find the offer worthwhile given legal backing and mutual benefits (safe rum shipping). He assumes Alfie is rational and profit-oriented.

Alfie’s Counter – 100%

Alfie reveals a much higher demand with a threat attached (Ollie + gun). He’s signaling that he thinks Tommy has little to no leverage – a strong prior that Tommy is bluffing or weak.

Tommy’s Threat – Grenade

Tommy introduces new evidence: a possible suicide mission, planted grenade, anarchist partner. Alfie must now update his beliefs:

- What is the probability Tommy is bluffing?

- What’s the chance the grenade exists and is armed?

Ollie’s Confirmation – “He tied his lace…”

This is independent corroborating evidence – evidence of something anyway. Alfie now receives a report that raises the likelihood Tommy’s story is true (P(E|¬H) drops, P(E|H) rises). So Alfie updates his belief in Tommy’s credibility, lowering his confidence that he can push for 100%.

The offer history, which controls their priors and posteriors:

- Alfie lowers from 100% → 65% (“I’ll bet 100 to 1”)

- Tommy rejects

- Alfie considers Tommy’s past form (“he blew up his own pub”)

This shifts the prior. Now P(Tommy is reckless and serious) is higher. - Alfie: 65% → 45%

- Tommy: Counters with 30%

- Tommy adds detail: WWI tunneling expertise, same grenade kit, he blew up a mine

- Alfie checks for inconsistency (“I heard they all got buried”)

Potential Bayesian disconfirmation. Is Tommy lying? - Tommy: “Three of us dug ourselves out” → resolves inconsistency

The model regains internal coherence. Alfie’s posterior belief in the truth of the grenade story rises again. - Final offer: 35%

They settle, each having adjusted credence in the other’s threat profile and willingness to follow through.

Analysis

Beliefs are not static. Each new statement, action, or contradiction causes belief shifts. Updates are directional, not precise. No character says “I now assign 65% chance…” but, since they are rational actors, their offers directly encode these shifts in valuation. We see behaviorally expressed priors and posteriors. Alfie’s movement from 100 to 65 to 45 to 35% is not arbitrary. It reflects updates in how much control he believes he has.

Credibility is a Bayesian variable. Tommy’s past (blowing up his own pub) is treated as evidence relevant to present behavior. Social proof is given by Ollie. Ollie panics on recalling that Tommy tied his shoe. Alfie chastises Ollie for being a child in a man’s world and sends him out. But Alfie has already processed this Bayesian evidence for the grenade threat, and Tommy knows it. The 7:00 deadline adds urgency and tension to the scene. Crucially, from a Bayesian perspective, it limits the number of possible belief revisions, a typical constraint for bounded rationality.

As an initial setup, let:

- T = Tommy has rigged a grenade

- ¬T = Tommy is bluffing

- P(T) = Alfie’s prior that Tommy is serious

Let’s say initially:

P(T) = 0.15, so P(¬T) = 0.85

Alfie starts with a strong prior that Tommy’s bluffing. Most people wouldn’t blow themselves up. Tommy’s a businessman, not a suicide bomber. Alfie has armed men and controls the room.

Sequence of Evidence and Belief Updates

Evidence 1: Tommy’s grenade threat

E₁ = Tommy says he planted a grenade and has an assistant with a tripwire

We assign:

- P(E₁|T) = 1 (he would say so if it’s real)

- P(E₁|¬T) = 0.7 (he might bluff this anyway)

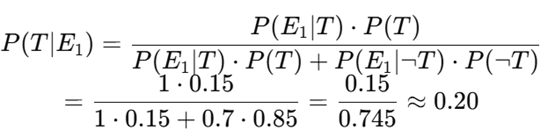

Using Bayes’ Theorem:

So now Alfie gives a 20% chance Tommy is telling the truth. Behavioral result: Alfie lowers the offer from 100% → 65%.

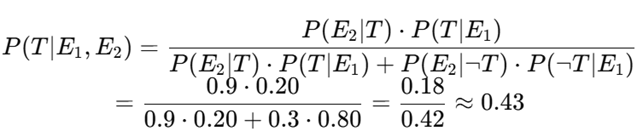

Evidence 2: Ollie confirms the lace-tying + nervousness

E₂ = Ollie confirms Tommy bent down and there’s a boy at the door

This is independent evidence supporting T.

- P(E₂|T) = 0.9 (if it’s true, this would happen)

- P(E₂|¬T) = 0.3 (could be coincidence)

Update:

So Alfie now gives 43% probability that the grenade is real. Behavioral result: Offer drops to 45%.

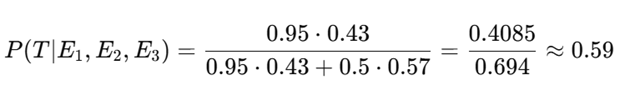

Evidence 3: Tommy shows grenade pin + WWI tunneler claim

E₃ = Tommy drops the pin and references real tunneling experience

- P(E₃|T) = 0.95 (he’d be prepared and have a story)

- P(E₃|¬T) = 0.5 (he might fake this, but riskier)

Update:

Now Alfie believes there’s nearly a 60% chance Tommy is serious. Behavioral result: Offer rises slightly to 35%, the final deal.

Simplified Utility Function

Assume Alfie’s utility is:

U(percent) = percent ⋅ V−C ⋅ P(T)

Where:

- V = Value of Tommy’s export business (let’s say 100)

- C = Cost of being blown up (e.g., 1000)

- P(T) = Updated belief Tommy is serious

So for 65%, with P(T) = 0.43:

U = 65 – 1000 ⋅ 0.43 = 65 – 430 = −365

But for 35%, with P(T) = 0.59:

U = 35 – 1000 ⋅ 0.59 = 35 – 590 = −555

Here we should note that Alfie’s utility function is not particularly sensitive to the numerical values of V and C; using C = 10,000 or 500 doesn’t change the relative outcomes much. So, why does Alfie accept the lower utility? Because risk of total loss is also a factor. If the grenade is real, pushing further ends in death and no gain. Alfie’s risk appetite is negatively skewed.

At the start of the negotiation, Alfie behaves like someone with low risk aversion by demanding 100%, assuming dominance, and later believing Tommy is bluffing. His prior is reflect extreme confidence and control. But as the conversation progresses, the downside risk becomes enormous: death, loss of business, and, likely worse, public humiliation.

The evidence increasingly supports the worst-case scenario. There’s no compensating upside for holding firm, no added reward for risking everything to get 65% instead of 35%.

This flips Alfie’s profile. He develops a sharp negative skew in risk appetite, especially under time pressure and mounting evidence. Even though 35% yields a worse expected utility than 65%, it avoids the long tail – catastrophic loss.

***

[Tommy is seated in Alfie’s office]

Alfie (to Tommy): That’ll probably be for you, won’t it?

Tommy: Hello? Arthur. You’re out.

Alfie: Right, so that’ll be your side of the street swept up, won’t it? Where’s mine? What you got for me?

Tommy: Signed by the Minister of the Empire himself. Yeah? So it is.

Tommy: This means that you can put your rum in our shipments, and no one at Poplar Docks will lift a canvas.

Alfie: You know what? I’m not even going to have my lawyer look at that.

Tommy: I know, it’s all legal.

Alfie: You know what, mate, I trust you. That’s that. Done. So, whisky… There is, uh, one thing, though, that we do need to discuss.

Tommy: What would that be?

Alfie: It says here, “20% “paid to me of your export business.”

Tommy: As we agreed on the telephone…

Alfie: No, no, no, no, no. See, I’ve had my lawyer draw this up for us, just in case. It says that, here, that 100% of your business goes to me.

Tommy: I see.

Alfie: It’s there.

Tommy: Right.

Alfie: Don’t worry about it, right, because it’s totally legal binding. All you have to do is sign the document and transfer the whole lot over to me.

Tommy: Sign just here, is it?

Alfie: Yeah.

Tommy: I see. That’s funny. That is.

Alfie: What?

Tommy: No, that’s funny. I’ll give you 100% of my business.

Alfie: Yeah.

Tommy: Why?

[Ollie appears and aims a revolver at Tommy]

Alfie: Ollie, no. No, no, no. Put that down. He understands, he understands. He’s a big boy, he knows the road. Now, look, it’s just non-fucking-negotiable. That’s all you need to know. So all you have to do is sign the fucking contract. Right there.

Tommy: just sign here?

Alfie: With your pen.

Tommy: I understand.

Alfie: Good. Get on with it.

Tommy: Well, I have an associate waiting for me at the door. I know that he looks like a choir boy, but he is actually an anarchist from Kentish Town.

Alfie: Tommy… I’m going to fucking shoot you. All right?

Tommy: Now, when I came in here, Mr. Solomons, I stopped to tie my shoelace. Isn’t that a fact? Ollie?

Tommy: I stopped to tie my shoelace. And while I was doing it, I laid a hand grenade on one of your barrels.

Tommy: Mark 15, with a wired trip. And my friend upstairs… Well, he’s like one of those anarchists that blew up Wall Street, you know? He’s a professional. And he’s in charge of the wire. If I don’t walk out that door on the stroke of 7:00, he’s going to trigger the grenade and… your very combustible rum will blow us all to hell. And I don’t care… because I’m already dead.

Ollie: He tied his lace, Alfie. And there is a kid at the door.

Tommy: From a good family, too. Ollie, it’s shocking what they become…

Alfie (to Ollie): What were you doing when this happened?

Ollie: He tied his lace, nothing else.

Alfie: Yeah, but what were you doing?

Ollie: I was marking the runners in the paper.

Alfie: What are you doing?

Tommy: Just checking the time. Carry on.

Alfie: Right, Ollie, I want you to go outside, yeah, and shoot that boy in the face – from the good family, all right?

Tommy: Anyone walks through that door except me, he blows the grenade.

Ollie: He tied his fucking lace…

Tommy: I did tie my lace.

Alfie: I bet, 100 to 1, you’re fucking lying, mate. That’s my money.

Tommy: Well, see, you’ve failed to consider the form. I did blow up me own pub… for the insurance.

Alfie: OK right… Well, considering the form, I would say 65 to 1. Very good odds. And I would be more than happy and agree if you were to sign over 65% of your business to me. Thank you.

Tommy: Sixty-five? No deal.

Alfie: Ollie, what do you say?

Ollie: Jesus Christ, Alfie. He tied his fucking lace, I saw him! He planted a grenade, I know he did. Alfie, it’s Tommy fucking Shelby…

[Alfie smacks Ollie across the face, grabs him by the collar, pulls him close and looks straight into his face.]

Alfie to Ollie: You’re behaving like a fucking child. This is a man’s world. Take your apron off, and sit in the corner like a little boy. Fuck off. Now.

Tommy: Four minutes.

Alfie: All right, four minutes. Talk to me about hand grenades.

Tommy: The chalk mark on the barrel, at knee height. It’s a Hamilton Christmas. I took out the pin and put it on the wire.

[Tommy produces a pin from his pocket and drops it on the table. Alfie inspects it.]

Alfie: Based on this… forty-five percent. [of Tommy’s business]

Tommy: Thirty.

Alfie: Oh, fuck off, Tommy. That’s far too little.

Tommy: In France, Mr. Solomons, while I was a tunneller, a clay-kicker. 179. I blew up Schwabenhöhe. Same kit I’m using today.

Alfie: It’s funny, that. I do know the 179. And I heard they all got buried.

[Alfie looks at Tommy as though he has caught him in an inconsistency]

Tommy: Three of us dug ourselves out.

Alfie: Like you’re digging yourself out now?

Tommy: Like I’m digging now.

Alfie: Fuck me. Listen, I’ll give you 35%. That’s your lot.

Tommy: Thirty-five.

[Tommy and Alfie shake hands. Tommy leaves.]

Gospel of Mark: A Masterpiece Misunderstood, Part 7 – Mark Before Modernism

Posted in History of Christianity on August 3, 2025

See Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6

In ancient Greek theater, like Sophocles’s Oedipus Rex, dramatic irony was central. Audiences knew Oedipus’s fate while he remained ignorant. This technique was carried into Roman drama, like Seneca’s tragedies. As described earlier, Christian writers moved away from irony in the late antique period.

During the Renaissance, Shakespeare used dramatic irony heavily. In Romeo and Juliet, the audience knows Juliet’s “death” is staged, but Romeo doesn’t. Such irony remained common in 17th- and 18th-century European drama, as in Molière’s comedies, but less structurally central than in Greek tragedy. The 19th century saw it in melodrama and novels (e.g., Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles), where readers grasped fates characters couldn’t.

In the 20th century, dramatic irony shifted. Modernist works like Brecht’s epic theater used it deliberately to alienate audiences, encouraging critical reflection. O’Neill’s plays (Long Day’s Journey into Night) leaned on it for emotional weight.

The Gospel of Mark seems to anticipate literary modernism. Mark didn’t invent stream of consciousness or set his gospel in a world of urban alienation. But the instincts of modernist storytelling – deliberate ambiguity, refusal to explain, the layering of voices, the elevation of reader above character, the fragmentary sense of time – are already alive in Mark. They are what make the gospel feel so strange to readers trained on the smoother harmonies of Matthew and Luke. In literary style, Mark seems to reach both far back, to the ancient Greeks, and far ahead, to modernism. He writes more as dramatist than as evangelist, putting him in unexpected company.

Withheld Meaning: Proust’s Readers and Mark’s

Modernist literature often refuses to say what it means. It circles themes without resolving them. It trusts the reader to infer. Mark gives riddles disguised as parables, miracles that aren’t explained, and a resurrection that isn’t shown. Not glory, but silence.

In Swann’s Way, Proust captures this same dynamic, not in plot, but in psychological structure. Swann, obsessively reading the behavior of the woman he loves, becomes a figure of frustrated interpretation:

“He belonged to that class of men who… are capable of discovering in the most insignificant action a symbol, a menace, a piece of evidence, and who are no more capable of not interpreting a movement of the person they love than a believer is of not interpreting a miracle.”

There’s the reader Mark aimed for, watching every detail, looking for signs.

Beckett and the Failed Witness

Beckett’s characters, like Vladimir and Estragon in Waiting for Godot and Winnie in Happy Days are excluded from understanding. They wait for voices that don’t explain, and they continue despite knowing the endpoint will never come.

Vladimir (Waiting for Godot): Suppose we repented.

Estragon: Repented what?

Vladimir: Oh… (He reflects.) We wouldn’t have to go into the details.

Estragon: Our being born?

In Mark, the reader continues after the characters collapse. The women flee the tomb. The disciples abandon the frame. The gospel stops, but the reader continues – because Mark has structured the story so that you see what they don’t.

Beckett once said that Joyce was always adding to his prose, and that he himself was working in the opposite direction: “I realized that my own way was in impoverishment, in lack of knowledge and in taking away.”

Mark takes away. He subtracts resurrection appearances and erases resolution. What remains is a void that insists on meaning – not through declaration, but through the reader’s isolation.

Unreliable Perception and Faulkner’s Disciples

In Faulkner’s works like The Sound and the Fury, characters narrate their experiences through fragmented, subjective lenses, often unaware of the full scope of their stories. Their voices – Quentin Compson’s anguished stream-of-consciousness or Addie Bundren’s posthumous reflections – clash and contradict, leaving gaps that the reader must navigate. This aligns with reader-response criticism, which emphasizes the reader’s active role in interpreting and reconstructing meaning from incomplete or biased accounts. Faulkner’s narrators don’t deliver a tidy “truth”; they offer perspectives clouded by personal trauma, guilt, or limited understanding. Quentin, for instance, obsesses over time and his sister Caddy’s fall, but his mental collapse distorts his narrative, forcing the reader to piece together the Compson family’s decay from his fractured memories and those of his brothers.

Faulkner’s unreliable narrators force the reader to rise above their limitations, synthesizing disparate voices to uncover a truth that no single character fully grasps.

Mark gives us the same through the disciples. They speak, but they are not to be trusted. They fear Jesus’s passion predictions and change the subject. And unlike Luke, Mark never rehabilitates them.

As with Faulkner, their unreliability is device. Mark lets them fall so you can rise, just as Faulkner allows Quentin’s breakdown to weave time, memory, and guilt into the fabric of the narrative. Faulkner’s chaos of competing voices reflects the human condition – fragmented, subjective, and burdened by history. In Mark, the disciples’ failures underscore the radical nature of Jesus’s mission, which defies human expectations of power and glory.

Beckett on the Death of the Subject

Samuel Beckett, writing on Proust in 1931, described the modern condition as a crisis, not of plot, but of self:

“We are not merely more weary because of yesterday, we are other, no longer what we were before the calamity of yesterday… The subject has died – and perhaps many times – on the way.”

This is the shape of Mark’s gospel. The narrator sees all but explains nothing. The disciples begin as named voices and end as absences. The final scene gives no resolution. Time, once galloping forward with Mark’s “immediately” at every step, halts in a tomb that no one enters.

The reader is left standing outside the story with a question its characters cannot answer.

Gospel of Ellipsis: Hemingway’s Surface Tension

Hemingway’s prose derives its emotional power from deliberate restraint, a technique often described as the “iceberg theory,” where the bulk of meaning lies beneath the surface of the text. In stories like Hills Like White Elephants, he employs sparse, minimalist dialogue and understated narration to convey profound emotional and thematic weight without explicitly stating the core issues. The story’s central conflict – an implied discussion about abortion between a man and a woman at a train station – is never directly named. Instead, Hemingway embeds the tension in clipped exchanges, pregnant pauses, and subtle imagery.

This restraint amplifies the emotional force by forcing readers to engage actively with the subtext. The silences between sentences – where characters avoid articulating their fears, desires, or regrets – carry the weight of unspoken truths. For example, when Jig says, “They look like white elephants,” and the man responds dismissively, the dialogue skirts the real issue, revealing their emotional disconnect and the power imbalance in their relationship. The unsaid looms larger than the said, making the reader feel the characters’ anxiety, uncertainty, and isolation.

Mark doesn’t explain the fig tree or narrate the resurrection. He doesn’t say why the women told no one. And when Jesus speaks cryptically, the narrator does not clarify. Mark doesn’t mismanage meaning, he suppresses it for effect. Like Hemingway, Mark trusts the reader to feel the weight of what isn’t said.

Kafka’s Gospel: Parable Without Answer

Kafka’s stories are often structured as parables – but not the kind that end in moral resolution. His parables frustrate the interpretive impulse. Their logic seems to point to something just beyond reach.

In Before the Law, a man spends his life trying to gain access to a door that was meant only for him. He dies without ever passing through. The priest in The Trial tells Joseph K. the parable – and then refuses to explain it.

In Mark 13:14, Jesus warns of an “abomination of desolation” and then stops mid-sentence. The narrator breaks in: “Let the reader understand.” Who is this reader? Not Peter, James, or John. You. Understand what? Mark’s narrator refuses to explain it.

Like Kafka, Mark knows the parable won’t resolve. He knows it exists to sharpen the hunger to understand. And the gospel itself becomes that hunger’s object.

Conclusion – Mark’s Gospel Came Too Soon

Even sympathetic readers struggle to see it. Because Mark says less the other gospels say, it is nearly impossible to read him without filling in what he left out. Harmonization is a habit learned in childhood. An untrained, unbiased, innocent reading – a first reading – by a western reader is almost unavailable. And so the masterpiece goes unnoticed because the broader story has been too thoroughly absorbed for the real Mark to be seen.

By theological or historical standards, Mark has long ranked lowest by far among the gospel writers. In early Christian citation, he accounts for barely 4% of gospel references. He is by far the shortest and the roughest, some say the least theologically rich. I disagree.

By modern literary standards – those that distrust omniscient narration and place the burden of meaning on the reader – Mark might be the rhetorical master of millennia.

That achievement is easily missed. I think it a shame that readers of modern literature rarely turn to the gospels, starting with Mark. And if they do, prior convictions prevent them from imagining it could house a work this strange, this far ahead of its time. Mark wasn’t experimenting with form for its own sake. He was a storyteller – one whose narrative instincts ran far ahead of his genre.

In his world of early Christianity, stories were expected to explain, miracles to prove, and heroes to be understood. Mark resists all of that. He gives us a Messiah who is misunderstood, a story that ends in silence, and a text that refuses to explain itself.

In other words, he wrote a modernist gospel – a work of quiet fire – before modernism existed.

Postscript: The Gospel That Leaves You Standing

Mark ends with absence– with flight, silence, and a rolled-away stone. That was the final move of a writer who trusted you to finish what he started.

Across this series, I haven’t treated Mark as theology but as what it so clearly is, once you stop trying to fix it: a story designed to be misunderstood by its characters and grasped by its reader. None of that should bear on your theology, beliefs, or lack thereof; it works regardless.

That story does not yield its truth by accumulating facts. It yields by withholding enough to make you reach. And when you do, something happens. You see what others miss. You feel the silence grow louder than the speech.

Even now, twenty centuries later, the final question still hangs–not in the mouths of the women at the tomb, but in yours: What are you going to do with what you’ve seen?

Gospel of Mark, Masterpiece Misunderstood, Part 6 – Mark, Paul and James: The Silence, the Self and the Law

Posted in History of Christianity on August 2, 2025

Mark vs. Matthew and Luke: Redaction, Not Clarification

Matthew and Luke didn’t set out to clarify Mark, as many scholars have claimed. They were authors writing for different communities with different needs. They either misunderstood Mark’s rhetorical style, understood it but disliked it, or were indifferent to it altogether, merely reusing his stories and text. They took Mark’s gospel and Q as starting points, then reshaped them to fit their theological goals. In doing so, they smoothed its edges, filled in its silences, and reframed its mysteries using their own rhetorical styles.

Matthew, by most accounts, is rhetorically more refined than Mark. His Greek is more polished, and his theological framing is clearer. But Matthew and Luke lose Mark’s vividness. In my view, the most rhetorically daring gospel in Christianity was overwritten by its successors, and it is inaccurate or disingenuous to frame this as clarification.

Matthew and Luke reworked the fig tree. Mark’s fig tree vignette (11:12–14, 20–21) is famously strange, as discussed earlier: Jesus curses a tree for having no fruit out of season and Mark wraps the episode around the cleansing of the temple to enforce the metaphor.

Matthew’s version (21:18–22) changes the tempo: the tree withers immediately. The temple scene is unlinked. And the point is made explicit: it’s a lesson about faith and prayer. Luke (13:6–9) avoids the destructive miracle and cursing the tree, giving instead a parable that calls for repentance while there’s still time. A summary shows the transformation:

| Feature | Mark | Matthew | Luke |

| Type | miracle + symbol | miracle + moral | parable |

| Timing of Withering | next day | immediate | not applicable |

| Commentary | faith and prayer | faith and prayer | repentance and mercy |

| Relation to Temple | surrounds cleansing | follows cleansing | precedes healing on sabbath |

| Theological Emphasis | judgment, irony, failure of temple | power, faith, moral clarity | warning, grace, call for repentance |

What was rhetorical structure in Mark becomes illustrative theology in Matthew and Luke. Riddle becomes sermon; the silence is gone.

A comparison of approaches to the fig tree shows the progression toward theological evolution and loss of irony:

| Detail | Mark | Matthew | Luke |

| Fig tree cursed | Yes | Yes | No (parable only) |

| Disciples mentioned | Yes: “heard it”, “Peter remembered” | Yes: they “marveled” | No |

| Delayed withering | Yes | No | N/A |

| Delayed narrative payoff | Yes | No | N/A |

| Irony/suspension | Yes | No | No |

A comparison of the way Mark and Matthew mention the disciples in this story shows still more about their rhetorical mindsets. Mark (11:14) reports:

And he said to it, “May no one ever eat fruit from you again.” And his disciples heard it. (ESV)

His disciples heard it? Of course they did. But what an odd thing for Mark, given his economic prose, to include. The statement doesn’t advance the plot and interprets nothing. No, this is Mark the author signaling that he’s hung Chekov’s gun (give a reader no false promises) on the wall. Take notice, something is going to happen, so remember what is being marked here.

What’s going to happen is that Jesus will cleanse the temple. The marker (they heard him) marks the curse and is a small, almost invisible trigger, narratively minimal, ironically loaded, and structurally strategic. Matthew and Luke steered clear. Mark delays firing Chekov’s gun until he returns to the tree. Bang, it’s dead.

Mark ends his gospel with silence and fear. The women flee the tomb. No resurrection appearances. “They said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid.”

Matthew and Luke add resurrection appearances, dialogue, comfort, and commissions. Matthew gives us theatrical effects: guards, earthquakes, angelic speech. Luke gives us the road to Emmaus, meals, and final instructions.

These endings do more than continue the story. They close a loop Mark left open. They give theological assurance where Mark offered emotional tension. By explaining what Mark left implied, they take the burden of interpretation off the reader and place it into the narrative.

Mark’s disciples are never right. They botch the parables and miss the miracles. They sleep, flee, and deny. Mark never resolves that arc. The disciples have no epiphany. Peter is given a beatitude in Matthew: “Blessed are you, Simon… you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church” (Matt. 16:17–18).

Luke dials back the disciples’ failures and paints a more stable community. By the time we reach Acts, the apostles are the theological center of gravity.

Modern scholarship tends to treat Matthew and Luke as consciously adapting Mark rather than misunderstanding him or cringing at his telling. But their treatment of the fig tree is revealing. Whether their changes stem from narrative or theological agendas, the result is a loss of Mark’s narrative complexity. In that sense, even if they didn’t misunderstand or dislike Mark’s meaning, they did dismantle his rhetorical scaffolding – and with it, the deeper tension he built into the scene.

In Mark, Jesus says explicitly that parables are designed to (in order that they) conceal, not clarify (4:11–12). It’s a shocking claim. Jesus doesn’t teach in parables to illustrate the truth, but to hide it from those unready to hear it. It’s a clear challenge to you to show your readiness.

Matthew retains many of the same parables but softens the intent. He writes:

This is why I speak to them in parables, because seeing they do not see… (Matt. 13:13)

The subtle change from “in order that” to “because” shifts the parables’ purpose from concealment to explanation. This contrast doesn’t result from translation; it’s present in the Koine manuscripts. I agree with scholars like R.T. France and Joel Marcus that Matthew must have deliberately changed Mark’s ἵνα to ὅτι to soften the implication that Jesus’s parables intentionally obscure truth. That implication was theologically problematic for Matthew. What Mark presents as rhetorical filtering, Matthew turns into compassionate pedagogy. Matthew and Luke, in moving away from literary puzzle toward religion, wrote for churches, for instruction, for catechesis. Their redactions obscured the most subversive thing Mark had done: trust the reader.

Paul vs. Mark

While the epistles – especially those commonly attributed to Paul – show formidable rhetorical skill, their style is strikingly different from Mark’s. Paul’s prose is argumentative, insistent, full of digression and appeal. He leads the reader, often with intensity, sometimes with exasperation, and always with a strong sense of his own position in the exchange. Paul’s voice dominates. There’s no narrative mask, little humble pretense. The authority of the letter comes not from its structure but from the voice behind it. Even Paul’s moments of self-deprecation – “I speak as a fool” – seem more performative than self-effacing.

In 2 Corinthians 11, Paul all but dares his audience to compare him to rival apostles, saying,

Are they Hebrews? so am I. Are they Israelites? so am I. Are they the seed of Abraham? so am I. Are they ministers of Christ? (I speak as one beside himself) I more; in labors more abundantly… (2 Cor 11:22-23 ASV)