Posts Tagged history

Fuck Trump: The Road to Retarded Representation

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science on April 2, 2025

-Bill Storage, Apr 2, 2025

On February 11, 2025, the American Federation of Government Employees (AFGE) staged a “Rally to Save the Civil Service” at the U.S. Capitol. The event aimed to protest proposed budget cuts and personnel changes affecting federal agencies under the Trump administration. Notable attendees included Senators Brian Schatz (D-HI) and Chris Van Hollen (D-MD), and Representatives Donald Norcross (D-NJ) and Maxine Dexter (D-OR).

Dexter took the mic and said that “we have to fuck Trump.” Later Norcross led a “Fuck Trump” chant. The senators and representatives then joined a song with the refrain, “We want Trump in jail.” “Fuck Donald Trump and Elon Musk,” added Rep. Mark Pocan (D-WI).

This sort of locution might be seen as a paradigmatic example of free speech and authenticity in a moment of candid frustration, devised to align the representatives with a community that is highly critical of Trump. On this view, “Fuck Trump” should be understood within the context of political discourse and rhetorical appeal to a specific audience’s emotions and cultural values.

It might also be seen as a sad reflection of how low the Democratic Party has sunk and how low the intellectual bar has dropped to become a representative in the US congress.

I mostly write here about the history of science, more precisely, about History of Science, the academic field focused on the development of scientific knowledge and the ways that scientific ideas, theories, and discoveries have evolved over time. And how they shape and are shaped by cultural, social, political, and philosophical contexts. I held a Visiting Scholar appointment in the field at UC Berkeley for a few years.

The Department of the History of Science at UC Berkeley was created in 1960. There in 1961, Thomas Kuhn (1922 – 1996) completed the draft of The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, which very unexpectedly became the most cited academic book of the 20th century. I was fortunate to have second-hand access to Kuhn through an 18-year association with John Heilbron (1924 – 2023), who, outside of family, was by far the greatest influence on what I spend my time thinking about. John, Vice-Chancellor Emeritus of the UC System and senior research fellow at Oxford, was Kuhn’s grad student and researcher while Kuhn was writing Structure.

I want to discuss here the uncannily direct ties between Thomas Kuhn’s analysis of scientific revolutions and Rep. Norcross’s chanting “Fuck Trump,” along with two related aspects of the Kuhnian aftermath. The second is academic precedents that might be seen as giving justification to Norcross’s pronouncements. Third is the decline in academic standards over the time since Kuhn was first understood to be a validation of cultural relativism. To make this case, I need to explain why Thomas Kuhn became such a big deal, what relativism means in this context, and what Kuhn had to do with relativism.

To do that I need to use the term epistemology. I can’t do without it. Epistemology deals with questions that were more at home with the ancient Greeks than with modern folk. What counts as knowledge? How do we come to know things? What can be known for certain? What counts as evidence? What do we mean by probable? Where does knowledge come from, and what justifies it?

These questions are key to History of Science because science claims to have special epistemic status. Scientists and most historians of science, including Thomas Kuhn, believe that most science deserves that status.

Kernels of scientific thinking can be found in the ancient Greeks and Romans and sporadically through the Middle Ages. Examples include Adelard of Bath, Roger Bacon, John of Salisbury, and Averroes (Ibn Rushd). But prior to the Copernican Revolution (starting around 1550 and exploding under Galileo, Kepler, and Newton) most people were happy with the idea that knowledge was “received,” either through the ancients or from God and religious leaders, or from authority figures of high social status. A statement or belief was considered “probable”, not if it predicted a likely future outcome but if it could be supported by an authority figure or was justified by received knowledge.

Scientific thinking, roughly after Copernicus, introduced the radical notion that the universe could testify on its own behalf. That is, physical evidence and observations (empiricism) could justify a belief against all prior conflicting beliefs, regardless of what authority held them.

Science, unlike the words of God, theologians, and kings, does not deal in certainty, despite the number of times you have heard the phrase “scientifically proven fact.” There is no such thing. Proof is in the realm of math, not science. Laws of nature are generalizations about nature that we have good reason to act as if we know them to be universally and timelessly true. But they are always contingent. 2 + 2 is always 4, in the abstract mathematical sense. Two atoms plus two atoms sometimes makes three atoms. It’s called fission or transmutation. No observation can ever show 2 + 2 = 4 to be false. In contrast, an observation may someday show E = MC2 to be false.

Science was contagious. Empiricism laid the foundation of the Enlightenment by transforming the way people viewed the natural world. John Locke’s empirical philosophy greatly influenced the foundation of the United States. Empiricism contrasts with rationalism, the idea that knowledge can be gained by shear reasoning and through innate ideas. Plato was a rationalist. Aristotle thought Plato’s rationalism was nonsense. His writings show he valued empiricism, though was not a particularly good empiricist (“a dreadfully bad physical scientist,” wrote Kuhn). 2400 years ago, there was tension between rationalism and empiricism.

The ancients held related concerns about the contrast between absolutism and relativism. Absolutism posits that certain truths, moral principles, and standards are universally and timelessly valid, regardless of perspectives, cultures, or circumstances. Relativism, in contrast, holds that truth, morality, and knowledge are context-sensitive and are not universal or timeless.

In Plato’s dialogue, Theaetetus, Plato, examines epistemological relativism by challenging his adversary Protagoras, who asserts that truth and knowledge are not absolute. In Theaetetus Socrates, Plato’s mouthpiece, asks, “If someone says, ‘This is true for me, but that is true for you,’ then does it follow that truth is relative to the individual?”

Epistemological relativism holds that truth is relative to a community. It is closely tied to the anti-enlightenment romanticism that developed in the late 1700s. The romantics thought science was spoiling the mystery of nature. “Our meddling intellect mis-shapes the beauteous forms of things: We murder to dissect,” wrote Wordsworth.

Relativism of various sorts – epistemological, moral, even ontological (what kinds of things exist) – resurged in the mid 1900s in poststructuralism and postmodernism. I’ll return to postmodernism later.

The contingent nature of scientific beliefs (as opposed to the certitude of math), right from the start in the Copernican era, was not seen by scientists or philosophers as support for epistemological relativism. Scientists – good ones, anyway – hold it only probable, not certain, that all copper is conductive. This contingent state of scientific knowledge does not, however, mean that copper can be conductive for me but not for you. Whatever evidence might exist for the conductivity of copper, scientists believe, can speak for itself. If we disagreed about conductivity, we could pull out an Ohmmeter and that would settle the matter, according to scientists.

Science has always had its enemies, at times including clerics, romantics, Luddites, and environmentalists. Science, viewed as an institution, could be seen as the monster that spawned atomic weapons, environmental ruin, stem cell hubris, and inequality. But those are consequences of science, external to its fundamental method. They don’t challenge science’s special epistemic status, but epistemic relativists do.

Relativism about knowledge – epistemological relativism – gained steam in the 1800s. Martin Heidegger, Karl Marx (though not intentionally), and Sigmund Freud, among others, brought the idea into academic spheres. While moral relativism and ethical pluralism (likely influenced by Friedrich Nietzsche) had long been in popular culture, epistemological relativism was sealed in Humanities departments, apparently because the objectivity of science was unassailable.

Enter Thomas Kuhn, Physics PhD turned historian for philosophical reasons. His Structure was originally published as a humble monograph in International Encyclopedia of Unified Science, then as a book in 1962. One of Kuhn’s central positions was that evidence cannot really settle non-trivial scientific debates because all evidence relies on interpretation. One person may “see” oxygen in the jar while another “sees” de-phlogisticated air. (Phlogiston was part of a theory of combustion that was widely believed before Antoine Lavoisier “disproved” it along with “discovering” oxygen.) Therefore, there is always a social component to scientific knowledge.

Kuhn’s point, seemingly obvious and innocuous in retrospect, was really nothing new. Others, like Michael Polanyi, had published similar thoughts earlier. But for reasons we can only guess about in retrospect, Kuhn’s contention that scientific paradigms are influenced by social, historical, and subjective factors was just the ammo that epistemological relativism needed to escape the confines of Humanities departments. Kuhn’s impact probably stemmed from the political climate of the 1960s and the detailed way he illustrated examples of theory-laden observations in science. His claim that, “even in physics, there is no standard higher than the assent of the relevant community” was devoured by socialists and relativists alike – two classes with much overlap in academia at that time. That makes Kuhn a relativist of sorts, but he still thought science to be the best method of investigating the natural world.

Kuhn argued that scientific revolutions and paradigm shifts (a term coined by Kuhn) are fundamentally irrational. That is, during scientific revolutions, scientific communities depart from empirical reasoning. Adherents often defend their theories illogically, discounting disconfirming evidence without grounds. History supports Kuhn on this for some cases, like Copernicus vs. Ptolemy, Einstein vs. Newton, quantum mechanics vs. Einstein’s deterministic view of the subatomic, but not for others like plate tectonics and Watson and Crick’s discovery of the double-helix structure of DNA, where old paradigms were replaced by new ones with no revolution.

The Strong Programme, introduced by David Bloor, Barry Barnes, John Henry and the Edinburgh School as Sociology of Scientific Knowledge (SSK), drew heavily on Kuhn. It claimed to understand science only as a social process. Unlike Kuhn, it held that all knowledge, not just science, should be studied in terms of social factors without privileging science as a special or uniquely rational form of knowledge. That is, it denied that science had a special epistemic status and outright rejected the idea that science is inherently objective or rational. For the Strong Programme, science was “socially constructed.” The beliefs and practices of scientific communities are shaped solely by social forces and historical contexts. Bloor and crew developed their “symmetry principle,” which states that the same kinds of causes must be used to explain both true and false scientific beliefs.

The Strong Programme folk called themselves Kuhnians. What they got from Kuhn was that science should come down from its pedestal, since all knowledge, including science, is relative to a community. And each community can have its own truth. That is, the Strong Programmers were pure epistemological relativists. Kuhn repudiated epistemological relativism (“I am not a Kuhnian!”), and to his chagrin, was still lionized by the strong programmers. “What passes for scientific knowledge becomes, then, simply the belief of the winners. I am among those who have found the claims of the strong program absurd: an example of deconstruction gone mad.” (Deconstruction is an essential concept in postmodernism.)

“Truth, at least in the form of a law of noncontradiction, is absolutely essential,” said Kuhn in a 1990 interview. “You can’t have reasonable negotiation or discourse about what to say about a particular knowledge claim if you believe that it could be both true and false.”

No matter. The Strong Programme and other Kuhnians appropriated Kuhn and took it to the bank. And the university, especially the social sciences. Relativism had lurked in academia since the 1800s, but Kuhn’s scientific justification that science isn’t justified (in the eyes of the Kuhnians) brought it to the surface.

Herbert Marcuse, ” Father of the New Left,” also at Berkeley in the 1960s, does not appear to have had contact with Kuhn. But Marcuse, like the Strong Programme, argued that knowledge was socially constructed, a position that Kuhnians attributed to Kuhn. Marcuse was critical of the way that Enlightenment values and scientific rationality were used to legitimize oppressive structures of power in capitalist societies. He argued that science, in its role as part of the technological apparatus, served the interests of oppressors. Marcuse saw science as an instrument of domination rather than emancipation. The term “critical theory” originated in the Frankfurt School in the early 20th century, but Marcuse, once a main figure in Frankfurt’s Institute for Social Research, put Critical Theory on the map in America. Higher academics began its march against traditional knowledge, waving the banners of Marcusian cynicism and Kuhnian relativism.

Postmodernism means many things in different contexts. In 1960s academia, it referred to a reaction against modernism and Enlightenment thinking, particularly thought rooted in reason, progress, and universal truth. Many of the postmodernists saw in Kuhn a justification for certain forms of both epistemic and moral relativism. Prominent postmodernists included Jean-François Lyotard, Michel Foucault, Jean Baudrillard, Richard Rorty, and Jacques Derrida. None of them, to my knowledge, ever made a case for unqualified epistemological relativism. Their academic intellectual descendants often do.

20th century postmodernism had significant intellectual output, a point lost on critics like Gross and Levitt (Higher Superstition, 1994) and Dinesh De Souza. Derrida’s application of deconstruction of written text took hermeneutics to a new level and has proved immensely valuable to analysis of ancient texts, as has the reader-response criticism approach put forth by Louise Rosenblatt (who was not aligned with the radical skepticism typical of postmodernism) and Jacques Derrida, and embraced by Stanley Fish (more on whom below). All practicing scientists would benefit from Richard Rorty’s elaborations on the contingency of scientific knowledge, which are consistent with those held by Descartes, Locke, and Kuhn.

Michel Foucault attacked science directly, particularly psychology and, oddly, from where we stand today, sociology. He thought those sciences constructed a specific normative picture of what it means to be human, and that the farther a person was from the idealized clean-cut straight white western European male, the more aberrant those sciences judged the person to be. Males, on Foucault’s view, had repressed women for millennia to construct an ideal of masculinity that serves as the repository of political power. He was brutally anti-Enlightenment and was disgusted that “our discourse has privileged reason, science, and technology.” Modernity must be condemned constantly and ruthlessly. Foucault was gay, and for a time, he wanted sex to be the center of everything.

Foucault was once a communist. His influence on identity politics and woke ideology is obvious, but Foucault ultimately condemned communism and concluded that sexual identity was an absurd basis on which to form one’s personal identity.

Rosenblatt, Rorty, Derrida, and even at times Foucault, despite their radical positions, displayed significant intellectual rigor. This seems far less true of their intellectual offspring. Consider Sandra Harding, author of “The Gender Dimension of Science and Technology” and consultant to the U.N. Commission on Science and Technology for Development. Harding argues that the Enlightenment resulted in a gendered (male) conception of knowledge. She wrote in The Science Question in Feminism that it would be “illuminating and honest” to call Newton’s laws of motion “Newton’s rape manual.”

Cornel West, who has held fellowships at Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and Dartmouth, teaches that the Enlightenment concepts of reason and of individual rights, which were used since the Enlightenment were projected by the ruling classes of the West to guarantee their own liberty while repressing racial minorities. Critical Race Theory, the offspring of Marcuse’s Critical Theory, questions, as stated by Richard Delgado in Critical Race Theory, “the very foundations of the liberal order, including equality theory, legal reasoning, Enlightenment rationalism, and neutral principles of constitutional law.”

Allan Bloom, a career professor of Classics who translated Plato’s Republic in 1968, wrote in his 1987 The Closing of the American Mind on the decline of intellectual rigor in American universities. Bloom wrote that in the 1960s, “the culture leeches, professional and amateur, began their great spiritual bleeding” of academics and democratic life. Bloom thought that the pursuit of diversity and universities’ desire to increase the number of college graduates at any cost undermined the outcomes of education. He saw, in the 1960s, social and political goals taking priority over the intellectual and academic purposes of education, with the bulk of unfit students receiving degrees of dubious value in the Humanities, his own area of study.

At American universities, Marx, Marcuse, and Kuhn were invoked in the Humanities to paint the West, and especially the US, as cultures of greed and exploitation. Academia believed that Enlightenment epistemology and Enlightenment values had been stripped of their grandeur by sound scientific and philosophical reasoning (i.e. Kuhn). Bloom wrote that universities were offering students every concession other than education. “Openness used to be the virtue that permitted us to seek the good by using reason. It now means accepting everything and denying reason’s power,” wrote Bloom, adding that by 1980 the belief that truth is relative was essential to university life.

Anti-foundationalist Stanley Fish, Visiting Professor of Law at Yeshiva University, invoked Critical Theory in 1985 to argue that American judges should think of themselves as “supplementers” rather than “textualists.” As such, they “will thereby be marginally more free than they otherwise would be to infuse into constitutional law their current interpretations of our society’s values.” Fish openly rejects the idea of judicial neutrality because interpretation, whether in law or literature, is always contingent and socially constructed.

If Bloom’s argument is even partly valid, we now live in a second or third generation of the academic consequences of the combined decline of academic standards and the incorporation of moral, cultural, and epistemological relativism into college education. We have graduated PhDs in the Humanities, educated by the likes of Sandra Harding and Cornel West, who never should have been in college, and who learned nothing of substance there beyond relativism and a cynical disgust for reason. And those PhDs are now educators who have graduated more PhDs.

Peer reviewed journals are now being reviewed by peers who, by the standards of three generations earlier, might not be qualified to grade spelling tests. The academic products of this educational system are hired to staff government agencies, HR departments, and to teach school children Critical Race Theory, Queer Theory, and Intersectionality – which are given the epistemic eminence of General Relativity – and the turpitude of national pride and patriotism.

An example, with no offense intended to those who call themselves queer, would be to challenge the epistemic status of Queer Theory. Is it parsimonious? What is its research agenda? Does it withstand empirical scrutiny and generate consistent results? Do its theorists adequately account for disconfirming evidence? What bold hypothesis in Queer Theory makes a falsifiable prediction?

Herbert Marcuse’s intellectual descendants, educated under the standards detailed by Bloom, now comprise progressive factions within the Democratic Party, particularly those advocating socialism and Marxist-inspired policies. The rise of figures like Bernie Sanders, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and others associated with the “Democratic Socialists of America” reflects a broader trend in American politics toward embracing a combination of Marcuse’s critique of capitalism, epistemic and moral relativism, and a hefty decline in academic standards.

One direct example is the notion that certain forms of speech including reactionary rhetoric should not be tolerated if they undermine social progress and equity. Allan Bloom again comes to mind: “The most successful tyranny is not the one that uses force to assure uniformity but the one that removes the awareness of other possibilities.”

Echoes of Marcuse, like others of the 1960s (Frantz Fanon, Stokely Carmichael, the Weather Underground) who endorsed rage and violence in anti-colonial struggles, are heard in modern academic outrage that is seen by its adherents as a necessary reaction against oppression. Judith Butler of UC Berkeley, who called the October 2023 Hamas attacks an “act of armed resistance,” once wrote that “understanding Hamas, Hezbollah as social movements that are progressive, that are on the left, that are part of a global left, is extremely important.” College students now learn that rage is an appropriate and legitimate response to systemic injustice, patriarchy, and oppression. Seing the US as a repressive society that fosters complacency toward the marginalization of under-represented groups while striving to impose heteronormativity and hegemonic power is, to academics like Butler, grounds for rage, if not for violent response.

Through their college educations and through ideas and rhetoric supported by “intellectual” movements bred in American universities, politicians, particularly those more aligned with relativism and Marcuse-styled cynicism, feel justified in using rhetorical tools born of relaxed academic standards and tangential admissions criteria.

In the relevant community, “Fuck Trump” is not an aberrant tantrum in an echo chamber but a justified expression of solidary-building and speaking truth to power. But I would argue, following Bloom, that it reveals political retardation originating in shallow academic domains following the deterioration of civic educational priorities.

Examples of such academic domains serving as obvious predecessors to present causes at the center of left politics include:

- 1965: Herbert Marcuse (UC Berkeley) in Repressive Tolerance argues for intolerance toward prevailing policies, stating that a “liberating tolerance” would consist of intolerance to right-wing movements and toleration of left-wing movements. Marcuse advanced Critical Theory and a form of Marxism modified by genders and races replacing laborers as the victims of capitalist oppression.

- 1971: Murray Bookchin’s (Alternative University, New York) Post-Scarcity Anarchism followed by The Ecology of Freedom (1982) introduce the eco-socialism that gives rise to the Green New Deal.

- 1980: Derrick Bell’s (New York University School of Law) “Brown v. Board of Education and the Interest-Convergence Dilemma” wrote that civil rights advance only when they align with the interests of white elites. Later, Bell, Kimberlé Crenshaw, and Richard Delgado (Seattle University) develop Critical Race Theory, claiming that “colorblindness” is a form of oppression.

- 1984: Michel Foucault’s (Collège de France) The Courage of Truth addresses how individuals and groups form identities in relation to truth and power. His work greatly informs Queer Theory, post-colonial ideology, and the concept of toxic masculinity.

- 1985: Stanley Fish (Yeshiva University) and Thomas Grey (Stanford Law School) reject judicial neutrality and call for American judges to infuse into constitutional law their current interpretations of our society’s values.

- 1989: Kimberlé Crenshaw of Columbia Law School introduced the concept of Intersectionality, claiming that traditional frameworks for understanding discrimination were inadequate because they overlooked the ways that multiple forms of oppression (e.g., race, gender, class) interacted.

- 1990: Judith Butler’s (UC Berkeley) Gender Trouble introduces the concept of gender performativity, arguing that gender is socially constructed through repeated actions and expressions. Butler argues that the emotional well-being of vulnerable individuals supersedes the right to free speech.

- 1991: Teresa de Lauretis of UC Santa Cruz: introduced the term “Queer Theory” to challenge traditional understandings of gender and sexuality, particularly in relation to identity, norms, and power structures.

Marcusian cynicism might have simply died an academic fantasy, as it seemed destined to do through the early 1980s, if not for its synergy with the cultural relativism that was bolstered by the universal and relentless misreading and appropriation of Thomas Kuhn that permeated academic thought in the 1960s through 1990s. “Fuck Trump” may have happened without Thomas Kuhn through a different thread of history, but the path outlined here is direct and well-travelled. I wonder what Kuhn would think.

Popular Miscarriages of Science, part 3 – The Great Lobotomy Rush

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science on January 25, 2024

On Dec. 16, 1960, Dr. Walter Freeman told his 12-year-old patient Howard Dully that he was going to run some tests. Freeman then delivered four electric shocks to Dully to put him out, writing in his surgery notes that three would have been sufficient. Then Freeman inserted a tool resembling an ice pick above Dully’s eye socket and drove it several inches into his brain. Dully’s mother had died five years earlier. His stepmother told Freeman, a psychiatrist, that Dully had attacked his brother, something the rest of Dully’s family later said never happened. It was enough for Freeman to diagnose Dully as schizophrenic and perform another of the thousands of lobotomies he did between 1936 and 1967.

“By some miracle it didn’t turn me into a zombie,” said Dully in 2005, after a two-year quest for the historical details of his lobotomy. His story got wide media coverage, including an NPR story called My Lobotomy’: Howard Dully’s Journey. Much of the media coverage of Dully and lobotomies focused on Walter Freeman, painting Freeman as a reckless and egotistical monster.

Weston State Hospital (Trans-Allegheny Lunatic Asylum), photo courtesy of Tim Kiser

In The Lobotomy Letters: The Making of American Psychosurgery, (2015) Mical Raz asks, “Why, during its heyday was there nearly no objection to lobotomy in the American medical community?” Raz doesn’t seem to have found a satisfactory answer.

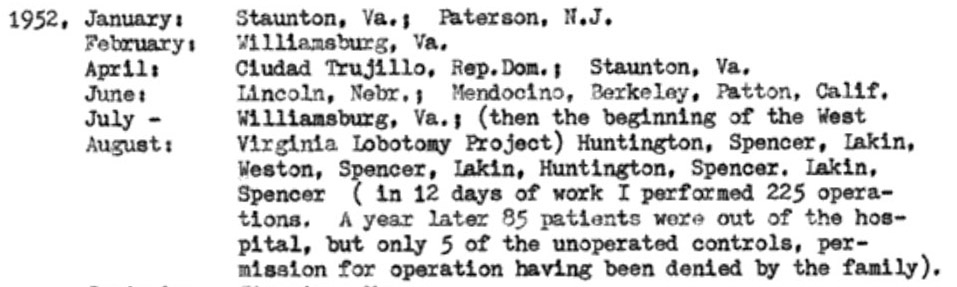

(I’m including a lot of in-line references here, not to be academic, but because modern media coverage often disagrees with primary sources and scholarly papers on the dates, facts, and numbers of lobotomy. It appears that most popular media coverage seemed to use other current articles as their sources, rather than going to primary sources. As a trivial example, Freeman’s notes report that in Weston, WV, he did 225 lobotomies in 12 days. The number 228 is repeated in all the press on Howard Dully. This post is on the longer side, because the deeper I dug, the less satisfied I became that we have learned the right lesson from lobotomies.)

A gripping account of lobotomies appeared in Dr. Paul Offit’s (developer of the rotavirus vaccine) 2017 Pandora’s Lab. It tells of a reckless Freeman buoyed by unbridled media praise. Offit’s piece concludes with a warning about wanting quick fixes. If it seems too good to be true, it probably is.

In the 2005 book, The Lobotomist: A Maverick Medical Genius and his Tragic Quest to Rid the World of Mental Illness, Jack El-Hai gave a much more nuanced account, detailing many patients who thought their lobotomies hade greatly improved their lives. El-Hai’s Walter Freeman was on a compassionate crusade to help millions of asylum patients escape permanent incarceration in gloomy state mental institutions. El-Hai documents Freeman’s life-long postoperative commitment to his patients, crisscrossing America to visit the patients that he had crisscrossed America to operate on. Despite performing most of his surgery in state mental hospitals, Freeman always refused to operate on people in prison, against pressure from defense attorneys’ pleas to render convicts safe for release.

Contrasting El-Hai’s relatively kind assessment, the media coverage of Dully aligns well with Offit’s account in Pandora’s Lab. On researching lobotomies, opinions of the medical community, and media coverage, I found I disagreed with Offit’s characterization of the media coverage, more about which below. In all these books I saw signs that lobotomies are a perfect instance of bad science in the sense of what Thomas Kuhn and related thinkers would call bad science, so I want to dig into that here. I first need to expand on Kuhn, his predecessors, and his followers a bit.

Kuhn’s Precursors and the Kuhnian Groupies

Kuhn’s writing, particularly Structure of Scientific Revolutions, was unfortunately ambiguous. His friends, several of whom I was lucky enough to meet, and his responses to his critics tell us that he was no enemy of science. He thought science was epistemically special. But he thought science’s claims to objectivity couldn’t be justified. Science, in Kuhn’s view, was not simply logic applied to facts. In Structure, Kuhn wrote many things that had been said before, though by sources Kuhn wasn’t aware of.

Karl Marx believed that consciousness was determined by social factors and that thinking will always be ideological. Marx denied that what Francis Bacon (1561-1626) had advocated was possible. I.e., we can never intentionally free our minds of the idols of the mind, the prejudices resulting from social interactions and from our tribe. Kuhn partly agreed but thought that communities of scientists engaged in competitive peer review could still do good science.

Ludwik Fleck’s 1935 Genesis and Development of a Scientific Fact argued that science was a thought collective of a community whose members share values. In 1958, Norwood Hanson, in Patterns of Discovery, wrote that all observation is theory-laden. Hanson agreed with Marx that neutral observation cannot exist, so neither can objective knowledge. “Seeing is an experience. People see, not their eyes,” said Hanson.

Most like Kuhn was Michael Polanyi, a brilliant Polish polymath (chemist, historian, economist). In his 1946 Science, Faith and Society, Polanyi wrote that scientific knowledge was produced by individuals under the influence of the scientific collectives in which they operated. Polanyi long preceded Kuhn, who was unaware of Polanyi’s work, in most of Kuhn’s key concepts. Unfortunately, Polanyi’s work didn’t appear in English until after Kuhn was famous. An aspect of Polanyi’s program important to this look at lobotomies is his idea that competition in science works like competition in business. The “market” determines winners of competing theories based on the judgments of its informed participants. Something like a market process exists within the institutional structure of scientific research.

Kuhn’s Structure was perfectly timed to correspond to the hippie/protest era, which distrusted big pharma and the rest of science, and especially the cozy relationships between academia, government, and corporations – institutions of social and political power. Kuhn had no idea that he was writing what would become one of the most influential books of the century, and one that became the basis for radical anti-science perspectives. Some communities outright declared war on objectivity and rationality. Science was socially constructed, said these “Kuhnians.” Kuhn was appalled.

A Kuhnian Take on Lobotomies

Folk with STEM backgrounds might agree that politics and influence can affect which scientific studies get funded but would probably disagree with Marx, Fleck, and Hanson that interest, influence, and values permeate scientific observations (what evidence gets seen and how it is assimilated), the interpretation of measurements and data, what data gets dismissed as erroneous or suppressed, and finally the conclusions drawn from observations and data.

The concept of social construction is in my view mostly garbage. If everything is socially constructed, then it isn’t useful to say of any particular thing that it is socially constructed. But the Kuhnians, who, oddly, have now come to trust institutions like big pharma, government science, and Wikipedia, were right in principle that science is in some legitimate sense socially constructed, though they were perhaps wrong about the most egregious cases, then and now. The lobotomy boom seems a good fit for what the Kuhnians worried about.

If there is going to be a public and democratic body of scientific knowledge (science definition 2 above) based on scientific methods and testability (definition 1 above), some community of scientists has to agree on what has been tested and falsified for the body of knowledge to get codified and publicized. Fleck and Hanson’s positions apply here. To some degree, that forces definition 3 onto definitions 1 and 2. For science to advance mankind, the institution must be cognitively diverse, it must welcome debate and court refutation, and it must be transparent. The institutions surrounding lobotomies did none of these. Monstrous as Freeman may have been, he was not the main problem – at least not the main scientific problem – with lobotomies. This was bad institutional science, and to the extent that we have missed what was bad about it, it is ongoing bad science. There is much here to make your skin crawl that was missed by NPR, Offit’s Pandora’s Lab, and El-Hai’s The Lobotomist.

Background on Lobotomy

In 1935 António Egas Moniz (1874–1955) first used absolute alcohol to destroy the frontal lobes of a patient. The Nobel Committee called it one of the most important discoveries ever made in psychiatric medicine, and Moniz became a Nobel laureate in 1949. In two years Moniz oversaw about 40 lobotomies. He failed to report cases of vomiting, diarrhea, incontinence, hunger, kleptomania, disorientation, and confusion about time in postoperative patients who lacked these conditions before surgery. When the surgery didn’t help the schizophrenia or whatever condition it was done to cure, Moniz said the patients’ conditions had been too advanced before the surgery.

In 1936 neurologist Walter Freeman, having seen Moniz’s work, ordered the first American lobotomy. James Watts of George Washington University Hospital performed the surgery by drilling holes in the side of the skull and removing a bit of brain. Before surgery, Freeman lied to the patient, who was concerned that her head would be shaved, about the procedure. She didn’t consent, but her husband did. The operation was done anyway, and Freeman declared success. He was on the path to stardom.

The patient, Alice Hammatt, reported being happy as she recovered. A week after the operation, she developed trouble communicating, was disoriented, and experienced anxiety, the condition the lobotomy was intended to cure. Freeman presented the case at a medical association meeting, calling the patient cured. In that meeting, Freeman was surprised to find that he faced criticism. He contacted the local press and offered an exclusive interview. He believed that the press coverage would give him a better reception at his next professional lobotomy presentation.

By 1952, 18,000 lobotomies had been performed in the US, 3000 of which Freeman claimed to have done. He began doing them himself, despite having no training in surgery, after Watts cut ties because of Freeman’s lack of professionalism and sterilization. Technically, Freeman was allowed to perform the kind of lobotomies he had switched to, because it didn’t involve cutting. Freeman’s new technique involved using a tool resembling an ice pick. Most reports say it was a surgical orbitoclast, though Freeman’s son Frank reported in 2005 that his father’s tool came right out their kitchen cabinet. Freeman punched a hole through the eye sockets into the patient’s frontal lobes. He didn’t wear gloves or a mask. West Virginians received a disproportionate share of lobotomies. At the state hospital in Weston, Freeman reports 225 lobotomies in twelve days, averaging six minutes per procedure. In The Last Resort: Psychosurgery and the Limits of Medicine (1999), JD Pressman reports a 14% mortality rate in Freeman’s operations.

The Press at Fault?

The press is at the center of most modern coverage of lobotomies. In Pandora’s Lab, Offit, as in other recent coverage, implies that the press overwhelmingly praised the procedure from day one. Offit reports that a front page article in the June 7, 1937 New York Times “declared – ‘in what read like a patent medicine advertisement – that lobotomies could relieve ‘tension apprehension, anxiety, depression, insomnia, suicidal ideas, …’ and that the operation ‘transforms wild animals into gentle creatures in the course of a few hours.’”

I read the 1937 Times piece as far less supportive. In the above nested quote, The Times was really just reporting the claims of the lobotomists. The headline of the piece shows no such blind faith: “Surgery Used on the Soul-Sick; Relief of Obsessions Is Reported.” The article’s subhead reveals significant clinical criticism: “Surgery Used on the Soul-Sick Relief of Obsessions Is Reported; New Brain Technique Is Said to Have Aided 65% of the Mentally Ill Persons on Whom It Was Tried as Last Resort, but Some Leading Neurologists Are Highly Skeptical of It.”

The opening paragraph is equally restrained: “A new surgical technique, known as “psycho-surgery,” which, it is claimed, cuts away sick parts of the human personality, and transforms wild animals into gentle creatures in the course of a few hours, will be demonstrated here tomorrow at the Comprehensive Scientific Exhibit of the American Medical Association…“

Offit characterizes medical professionals as being generally against the practice and the press as being overwhelmingly in support, a portrayal echoed in NPR’s 2005 coverage. I don’t find this to be the case. By Freeman’s records, most of his lobotomies were performed in hospitals. Surely the administrators and staff of those hospitals were medical professionals, so they couldn’t all be against the procedure. In many cases, parents, husbands, and doctors ordered lobotomies without consent of the patient, in the case of institutionalized minors, sometimes without consent of the parents. The New England Journal of Medicine approved of lobotomy, but an editorial in the 1941 Journal of American Medical Association listed the concerns of five distinguished critics. As discussed below, two sub-communities of clinicians may have held opposing views, and the enthusiasm of the press has been overstated.

In a 2022 paper, Lessons to be learnt from the history of lobotomy, Oivind Torkildsen of the Department of Clinical Medicine at University of Bergen wrote that “the proliferation of the treatment largely appears to have been based on Freeman’s charisma and his ability to enthuse the public and the news media.” Given that lobotomies were mostly done in hospitals staffed by professionals ostensibly schooled in and practicing the methods of science, this seems a preposterous claim. Clinicians would not be swayed by tabloids.

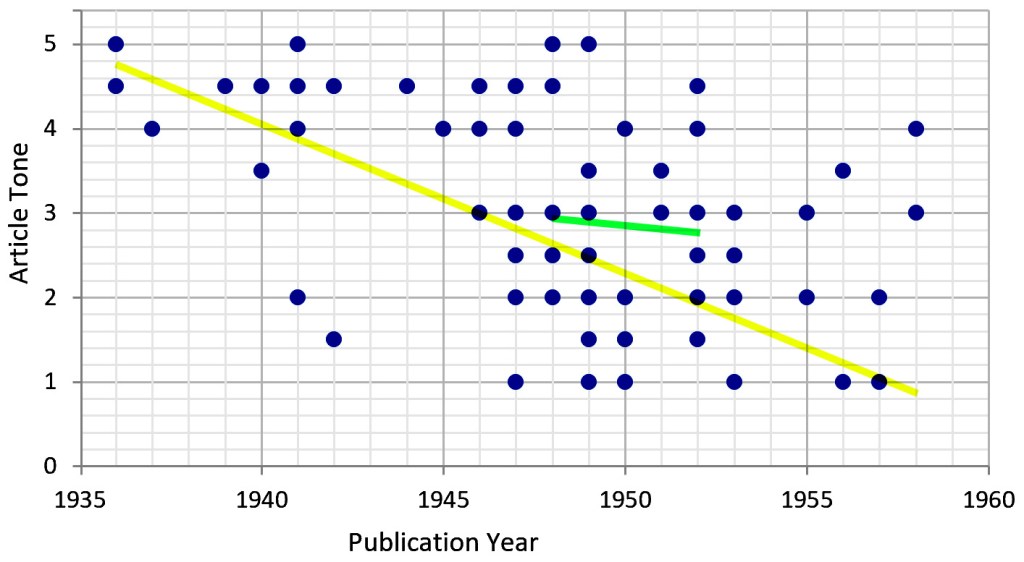

A 1999 article by GJ Diefenbach in the Journal of the History of the Neurosciences, Portrayal of Lobotomy in the Popular Press: 1935-1960, found that the press initially used uncritical, sensational reporting styles, but became increasingly negative in later years. The article also notes that lobotomies faced considerable opposition in the medical community. It concluded that popular press may have been a factor influencing the quick and widespread adoption of lobotomy.

The article’s approach was to randomly distribute articles to two evaluators for quantitative review. The reviewers then rated the tone of the article on a five-point scale. I plotted its data, and a linear regression (yellow line below) indeed shows that the non-clinical press cooled on lobotomies from 1936 to 1958 (though, as is apparent from the broad data scatter, linear regression doesn’t tell the whole story). But the records, spotty as they are, of when the bulk of lobotomies were performed should also be considered. Of the 20,000 US lobotomies, 18,000 of them were done in the 5-year period from 1948 to 1952, the year that phenothiazines entered psychiatric clinical trials. A linear regression of the reviewers’ judgements over that period (green line) shows little change.

Applying the Methods of History and Philosophy of Science

One possibility for making sense of media coverage in the time, the occurrence of lobotomies, and the current perception of why lobotomies persisted despite opposition in the medical community is to distinguish between lobotomies done in state hospitals from those done in private hospitals or psychiatrists’ offices. The latter category dominated the press in the 1940s and modern media coverage. The tragic case of Rosemary Kennedy, whose lobotomy left her institutionalized and abandoned by her family and that of Howard Dully are far better known that the 18,000 lobotomies done in American asylums. Americans were not as in love with lobotomies as modern press reports. The latter category, private hospital lobotomies, while including some high-profile cases, was small compared to the former.

Between 1936 and 1947, only about 1000 lobotomies had been performed in the US, despite Howard Freeman’s charisma and self-promotion. We, along with Offit and NPR, are far too eager to assign blame to Howard Freeman the monster than to consider that the relevant medical communities and institutions may have been monstrous by failing to critically review their results during the lobotomy boom years.

This argument requires me to reconcile the opposition to lobotomies appearing in medical journals from 1936 on with the blame I’m assigning to that medical community. I’ll start by noting that while clinical papers on lobotomy were plentiful (about 2000 between 1936 and 1952), the number of such papers that addressed professional ethics or moral principles was shockingly small. Jan Frank, in Some Aspects of Lobotomy (Prefrontal Leucotomy) under Psychoanalytic Scrutiny (Psychiatry 13:1, 1950) reports a “conspicuous dearth of contributions to the theme.” Constance Holden, in Psychosurgery: Legitimate Therapy or Laundered Lobotomy? (Science, Mar. 16, 1973), concluded that by 1943, medical consensus was against lobotomy, and that is consistent with my reading of the evidence.

Enter Polanyi and the Kuhnians

In 2005, Dr. Elliot Valenstein (1923-2023), 1976 author of Great and Desperate Cures: The Rise and Decline of Psychosurgery, in commenting on the Dully story, stated flatly that “people didn’t write critical articles.” Referring back to Michael Polanyi’s thesis, the medical community failed itself and the world by doing bad science – in the sense that suppression of opposing voices, whether through fear of ostracization or from fear of retribution in the relevant press, destroyed the “market’s” ability to get to the truth.

By 1948, the popular lobotomy craze had waned, as is shown in Diefenbach’s data above, but the institutional lobotomy boom had just begun. It was tucked away in state mental hospitals, particularly in California, West Virginia, Virginia, Washington, Ohio, and New Jersey.

Jack Pressman, in Last resort: Psychosurgery and the Limits of Medicine (1998), seems to hit the nail on the head when he writes “the kinds of evaluations made as to whether psychosurgery worked would be very different in the institutional context than it was in the private practice context.”

Doctors in asylums and mental hospitals lived in a wholly different paradigm from those in for-profit medicine. Funding in asylums was based on patient count rather than medical outcome. Asylums were allowed to perform lobotomies without the consent of patients or their guardians, to whom they could refuse visitation rights.

While asylum administrators usually held medical or scientific degrees, their roles as administrators in poorly funded facilities altered their processing of the evidence on lobotomies. Asylum administrators had a stronger incentive than private practices to use lobotomies because their definitions of successful outcome were different. As Freeman wrote in a 1957 follow-up of 3000 patients, lobotomized patients “become docile and are easier to manage”. Success in the asylum was not a healthier patient, it was a less expensive patient. The promise of a patient’s being able to return to life outside the asylum was a great incentive for administrators on tight budgets. If those administrators thought lobotomy was ineffective, they would have had no reason to use it, regardless of their ethics. The clinical press had already judged it ineffective, but asylum administrators’ understanding of effectiveness was different from that of clinicians in private practice.

Pressman cites the calculus of Dr. Mesrop Tarumianz, administrator of Delaware State Hospital: “In our hospital, there are 1,250 cases and of these about 180 could be operated on for $250 per case. That will constitute a sum of $45,000 for 180 patients. Of these, we will consider that 10 percent, or 18, will die, and a minimum of 50 percent of the remaining, or 81 patients will become well enough to go home or be discharged. The remaining 81 will be much better and more easily cared for the in hospital… That will mean a savings $351,000 in a period of ten years.”

The point here is not that these administrators were monsters without compassion for their patients. The point is that significant available evidence existed to conclude that lobotomies were somewhere between bad and terrible for patients, and that this evidence was not processed by asylum administrators in the same way it was in private medical practice.

The lobotomy boom was enabled by sensationalized headlines in the popular press, tests run without control groups, ridiculously small initial sample sizes, vague and speculative language by Moniz and Freeman, cherry-picked – if not outright false – trial results, and complacence in peer review. Peer review is meaningless unless it contains some element of competition.

Some might call lobotomies a case of conflict of interest. To an extent that label fits, not so much in the sense that anyone derived much personal benefit in their official capacity, but in that the aims and interests of the involved parties – patients and clinicians – were horribly misaligned.

The roles of asylum administrators – recall that they were clinicians too – did not cause them to make bad decisions about ethics. Their roles caused and allowed them to make bad decisions about lobotomy effectiveness, which was an ethics violation because it was bad science. Different situations in different communities – private and state practices – led intelligent men, interpreting the same evidence, to reach vastly different conclusions about pounding holes in people’s faces.

It will come as no surprise to my friends that I will once again invoke Paul Feyerabend: if science is to be understood as an institution, there must be separation of science and state.

___

Epilogical fallacies

A page on the official website the Nobel prize still defends the prize awarded to Moniz. It uncritically accepts Freeman’s statistical analysis of outcomes, e.g., 2% of patients became worse after the surgery.

…

Wikipedia reports that 60% of US lobotomy patients were women. Later in the same article it reports that 40% of US lobotomies were done on gay men. Thus, per Wikipedia, 100% of US male lobotomy patients were gay. Since 18,000 of the 20,000 lobotomies done in the US were in state mental institutions, we can conclude that mental institutions in 1949-1951 overwhelmingly housed gay men. Histories of mental institutions, even those most critical of the politics of deinstitutionalization, e.g. Deinstitutionalization: A Psychiatric Titanic, do not mention gay men.

…

Elliot Valenstein, cited above, wrote in a 1987 Orlando Sentinel editorial that all the major factors that shaped the lobotomy boom are still with us today: “desperate patients and their families still are willing to risk unproven therapies… Ambitious doctors can persuade some of the media to report untested cures with anecdotal ‘research’… it could happen again.” Now let’s ask ourselves, is anything equivalent going on today, any medical fad propelled by an uncritical media and single individual or small cadre of psychiatrists, anything that has been poorly researched and might lead to disastrous outcomes? Nah.

Recent Comments