The Gospel of Mark: A Masterpiece Misunderstood

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Christianity on July 28, 2025

PART 1 – Introduction and Premises

This series of posts is my attempt to distill a decade of notes on only one aspect of the Gospel of Mark. It’s long. I’ll divide it into digestible pieces. If you’re already familiar with biblical criticism, you might want to skip this post and move on to the next one.

Introduction

The Gospel of Mark is widely regarded as the earliest, the shortest, and the least theologically or rhetorically polished of the four canonical gospels. In early 20th-century scholarship. B. H. Streeter called Mark a “source document.” W. D. Davies, R. T. France, and Dale Allison describe Matthew as correcting or improving Mark’s syntax, arrangement, and clarity. Rudolf Bultmann famously dismissed Mark as a patchwork of oral units loosely strung together by a primitive eschatological framework. Mark accounts for just four percent of citations of the four gospels.

The idea, implicit or explicit, is that Mark is a rough draft. The real polish came later, first in Matthew, then in Luke, and ultimately in John, where style and theology finally reach their high form. This view depends on certain assumptions: that rhetorical excellence is a matter of formality and symmetry, that coherence requires direct explanation, and that more surface clarity leads to better persuasion, enlightenment, and epiphany.

What if Mark is playing a different game altogether? I’ll argue that the qualities that earlier critics judged as defects – abrupt transitions, ambiguity, repetition, narrative asymmetry – are not signs of immaturity but deliberate rhetorical strategies. What if the reader is not a passive recipient of doctrine, but the only character in the story intended to see clearly?

This essay argues that Mark’s lack of disclosure is calculated. I suggest that accepting the reader as a character in the story explains Mark’s apparent incongruities. By withholding, he provokes instead of sermonizing. Mark doesn’t seek exposition through polished antithesis. Instead, it combines dramatic irony drawn from the Greeks with innovations like rhetorical compression and a consistent narrative inversion of expectation. Where Matthew teaches, Mark tests, leaving characters in the dark, signaling to the reader through omission, and forcing interpretation through tension. Radical innovations in Mark’s time, these devices are common in 20th century literature.

This approach puts me, as writer of this essay, at odds with a long tradition of biblical criticism, but it frees a reader to see Mark on its own terms – as a standalone literary performance unequalled in the New Testament.

What follows is a reading of Mark attentive to narrative strategy, reader positioning, and the rhetorical use of silence, irony, and repetition. Along the way, I’ll contrast Mark with Matthew to highlight the aesthetic and rhetorical choices that shape each gospel’s voice. I’ll also compare Mark’s rhetorical approach to that of ancient Greeks, the other gospels, the epistles, and finally, to modern literature.

The focus here has gone largely unexamined: how the rhetorical effect of changes to Mark by Matthew and Luke reshapes the reader’s experience. What would a Christianity based solely on Mark look like? How would it feel?

One of the greatest barriers to reading Mark as Mark intended is overexposure to other gospels. Even more, it’s exposure to a whole cultural composite of “gospel truth,” much of it untethered from the texts themselves. Readers come to Mark not just having heard Matthew and Luke, but having absorbed centuries of harmonized retelling, devotional imagery, and theological overlay. They know what to expect. Shepherds, wise men, angels, a calm nativity scene, and Mary with a halo. And they see it even when it’s not there.

Nearly every nativity scene includes an ox and an ass, though no gospel mentions them. The Old Testament reference is clear (Isaiah 1:3), but the animals themselves are part of the interpretive afterlife of scripture, not scripture itself.

To read Mark on its own terms, to hear its urgency and feel its narrative shocks, you’d need to forget not only Matthew, Luke, John, and Acts, but centuries of art, sermons, and Christmas cards. If you could do that – if you could read Mark fresh – it would feel strange, stark, and full of unanswered questions. Mark wants his readers off-balance.

This analysis of Mark’s rhetoric relies on two premises, each widely but not universally accepted in biblical studies: Markan Priority and Short Ending. Markan Priority involves a related topic of scripture studies, the Synoptic Problem.

The Synoptic Problem

Matthew, Mark, and Luke share many of the same stories, sometimes word for word. Nearly 90% of Mark’s content appears in Matthew, and roughly 50% in Luke, sometimes verbatim. This cannot be merely coincidental. This shared structure and language is what scholars call the Synoptic Problem, because the gospels can be “seen together” (syn-optic), but don’t always agree. Who borrowed from whom?

The Two-Source Hypothesis posits that Mark and a hypothetical source called Q, containing material shared by Matthew and Luke but absent in Mark, account for the similarities and differences among the Gospels. Matthew and Luke sometimes agree in wording that is different from Mark. This logically necessitates the existence of Q by set theory: Q = (Luke ∩ Matthew) – Mark.

The possibility that Luke used Matthew directly (Farrer Hypothesis) eliminates the need for Q but faces challenges explaining Luke’s omitting major Matthean material. Other non-canonical source like Gospel of Thomas and the Logia of Jesus cloud the picture, and volumes have been written on the topic. But this simple summary, which roughly represents consensus, will serve our needs.

Markan Priority

Most scholars agree that Mark was the first of the canonical gospels to be written. Augustine of Hippo thought otherwise but did so on theological grounds. Markan priority has been the dominant view in New Testament studies for over a century.

Here’s why:

- Triple Tradition: Scholars estimate that 90–95% of the content in the Gospel of Mark (measured by verses or words) appears in either Matthew or Luke, often with similar wording or structure. Matthew incorporates about 600–620 of Mark’s 661 verses (90–93%), either verbatim or with modifications, while Luke includes about 350–400 (53–60%).

- Directional Dependence (redaction evidence): When Matthew and Luke both draw on the same Markan passage, they tend to revise or clarify Mark’s wording, suggesting they were using him as a source. The direction of influence runs from Mark to Matthew and from Mark to Luke because both sets of changes move from rough to refined.

- Theological Development: Mark’s accounts of events are often shorter, less polished, and present theological or narrative difficulties that Matthew and Luke appear to smooth over or “fix.” This suggests Mark was written first, and later authors refined its content to align with developing theological needs or to address potential misunderstandings. In Mark 6:5, Jesus “could not do any miracles” in Nazareth due to unbelief, implying a limitation. Matthew 13:58 softens this to “he did not do many miracles there because of their lack of faith,” removing the suggestion of inability. Mark 10:18 (“Why do you call me good?”) is similarly rephrased in Matthew 19:17.

- Indifference to the Synoptic Problem: The Two-Source Hypothesis posits that Matthew and Luke are based on Mark Q because minor agreements between Matthew and Luke necessitate it. Markan priority holds regardless of theory choice between Two-Source and Farrer.

- Markan Agreements: Matthew and Luke rarely agree against Mark, a pattern that fits if they both used him independently, but not if they used each other. Triadic comparison entails that if Matthew and Luke were independent, or if one used the other, you’d expect them to sometimes agree with each other against Mark. They rarely do. Instead, they either both agree with Mark or they diverge from Mark independently. The three synoptics share the healing of the paralytic (Mark 2:1–12; Matthew 9:1–8; Luke 5:17–26). Matthew and Luke deviate independently from Mark. Matthew simplifies the story, omitting details about the four men and the roof, and adds “Take heart” to Jesus’s words, a unique Matthean flourish. Luke retains Mark’s detail about the roof but specifies “through the tiles,” a detail absent in Mark. He changes “Son” to “Man” in Jesus’s address. The Parable of the Sower and the feeding miracles show similar independent deviations.

- Augustinian Hypothesis Flaws: Augustine’s Mark-as-summary theory entails that a Christian (Mark), in summarizing Matthew, could somehow deem the annunciation and virgin birth secondary details. Matthew 1:18–25 establishes Jesus’s divine origin. For early Christians, this element was central to the story of Jesus. Omitting core doctrinal claims in a summary would be unthinkable. Mark also lacks other material key to the Christian agenda including post-resurrection appearance and Sermon on the Mount.

If Mark came first, then Matthew and Luke aren’t just telling the same stories but are reacting directly to Mark, often repeating his words. And when they change him, we can learn a lot about what they found unacceptable or confusing.

Modern readers now have the opportunity to read Mark as I argue its author intended, though doing so isn’t easy, for reasons stated above. Mark’s omission of post-resurrection appearances and other key theological events are striking – and consequential. I hold that Mark was an original, complete work capable of delivering its message perfectly – for readers trained to read rhetorically and who treasure ironic writing.

This argument about Mark also relies on the notion that the short ending of Mark is the original, not the longer version.

Short Ending – the Manuscript Problem

The “short ending” of Mark’s Gospel ends abruptly at Mark 16:8:

And they went out and fled from the tomb, for trembling and astonishment had seized them, and they said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid. (ESV)

Whether this or a longer version that includes post-resurrection appearances was original has caused scholarly debate for centuries. Concluding with the women fleeing, afraid, and saying nothing seems anticlimactic or unsettling to many modern Christians, as it did in ancient times. Inerrantists often seek to harmonize Gospel accounts to maintain consistency, but some inerrantists, like the Evangelical Theological Society, conclude that the short ending is original and defend it as intentional, suggesting it conveys a theological point: awe at the resurrection. I agree.

More comprehensive analysis in recent decades leaves little doubt that the long version is a later addition:

- Manuscript Evidence The earliest and most reliable Greek manuscripts, such as Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Vaticanus (both 4th century), conclude the Gospel of Mark at 16:8, with the women fleeing in fear and saying nothing. So do the earliest Syriac and Latin translations. These manuscripts, considered among the best-preserved and closest to the original texts, show no trace of the Longer Ending (16:9–20). Additionally, no early manuscript ends mid-sentence or shows signs of physical damage (e.g., a torn page) that might suggest an accidental loss of text after 16:8. This textual stability in the earliest copies strongly supports the Short Ending as the original, as later manuscripts (from the 5th century onward) introduce the Longer Ending, indicating it was a subsequent addition rather than part of Mark’s original composition.

- External Testimony Early church fathers provide compelling evidence that the Short Ending was the original. Figures like Clement of Alexandria (late 2nd century) and Origen (early 3rd century) quote extensively from Mark but show no awareness of the Longer Ending (16:9–20), suggesting it was absent from their texts. Later, Eusebius and Jerome (4th century) explicitly note that the majority of Greek manuscripts known to them ended at 16:8 (at what we call 16:8 – numbered verses came much later), with Eusebius stating that “accurate” copies stopped there. This testimony from early Christian writers, combined with their silence on the Longer Ending, indicates that 16:8 was the widely accepted conclusion in the earliest centuries, before alternative endings appeared in later traditions.

- Textual Style and Vocabulary The Longer Ending (Mark 16:9–20) exhibits a distinct shift in style and vocabulary that sets it apart from the rest of Mark’s Gospel. Unlike Mark’s typically concise and vivid Greek, the Longer Ending uses words, such as poreuomai (“go”) and theaomai (“see”), that are absent elsewhere in Mark but common in later New Testament writings. Its polished, summary-like tone contrasts with Mark’s rugged narrative style. For example, the Longer Ending’s list of resurrection appearances and signs (handling snakes, drinking poison) feels formulaic and unlike Mark’s enigmatic storytelling. This linguistic discontinuity strongly suggests that 16:9–20 was written by a different author, likely to provide a more conventional conclusion.

- Abruptness Fits Mark’s Strategy The abrupt ending at Mark 16:8, with the women fleeing in “trembling and astonishment” and saying “nothing to anyone, for they were afraid,” aligns with Mark’s narrative strategy of emphasizing silence, mystery, ambiguity, and human failure. Throughout the Gospel, Mark portrays disciples who misunderstand Jesus (e.g., 8:21) and uses enigmatic statements to challenge readers (e.g., 4:11–12, where the purpose of parables is to obscure understanding for outsiders). The Short Ending’s lack of resolution invites readers to wrestle with the resurrection’s implications, fitting Mark’s pattern of leaving questions open-ended to provoke faith and reflection. This deliberate ambiguity makes the Short Ending consistent with Mark’s theological and literary goals, rather than a mistake or truncation.

- Internal Coherence The Short Ending at Mark 16:8 is internally coherent with the Gospel’s themes and tone. The women’s reaction is fear and silence in response to the angelic announcement of Jesus’ resurrection. This is a plausible human response to a divine encounter, echoing Mark’s portrayal of awe and fear elsewhere (e.g., 4:41, 5:15). In contrast, the Longer Ending shifts abruptly to a series of post-resurrection appearances and a commission, which feels like an attempt to resolve the ambiguity of 16:8 and align Mark with the more detailed accounts in Matthew and Luke. This shift disrupts the narrative flow and theological emphasis of Mark.

- Scribal Additions The Longer Ending appears in later manuscripts (from the 5th century onward, e.g., Codex Alexandrinus) and shows signs of being a composite text, likely drawn from elements in Matthew, Luke, and Acts (e.g., the Great Commission in Matthew 28:19–20, signs in Acts 2:4). Some manuscripts include an “Intermediate Ending” or other variants after 16:8, indicating scribal attempts to provide closure. These multiple endings suggest that later copyists, uncomfortable with the abruptness of 16:8, added material to make Mark’s conclusion more consistent with other gospel traditions.

On the matter of external testimony (2, above), I should say a bit more, because the argument here uses logic that comes up repeatedly in a study of Mark. The logic of this argument is what the ancients called argumentum ex silentio, an argument from silence. This reasoning infers a conclusion from the absence of evidence or statements where one might expect them.

Argument from silence is a contentious topic in biblical criticism. Apologist William Lane Craig challenges arguments from silence in debates, particularly on the matter of historicity. Apologist Greg Bahnsen judged arguments from silence sharply, arguing that unbelievers’ suppression of truth (Romans 1:18–20) makes silence on divine matters irrelevant.

But the silences supporting the Short Ending are from Christian writers themselves. Origen and Clement wrote lengthy, detailed analyses of what Mark had to say, but with no mention of Mark beyond 16:8. These prolific early Christian scholars focused on Christology, resurrection, and apostolic testimony, making it very likely they would have referenced the longer ending’s post-resurrection appearances (e.g., Jesus’s commission in 16:15-18) if they knew of them, because they align with their theological interests and would support their apologetic arguments. Their omission is not neutral; it’s powerful evidence that the longer ending was unknown to them.

Darrell J. Doughty (via Robert M. Price) proposed that Mark’s gospel may be circular in structure, the Short Ending intentionally echoing the beginning, prompting the reader to loop back to the opening scene of Jesus calling his disciples. While this idea remains speculative, the suggestion reflects a broader recognition that Mark’s structure is too intentional to be accidental.

The figure or figures responsible for assembling the New Testament canon – whether an ecclesiastical redactor, as David Trobisch argues, or a clerical-scribal network shaping a proto-canon – likely viewed the Short Ending of Mark as a theological and narrative deficiency. The women’s flight in fear and silence contrasts sharply with triumphant accounts in Matthew, Luke, and John, potentially creating unease for early Christians seeking a unified Gospel message. Despite this, the redactor or clerics recognized Mark’s foundational influence on Matthew and Luke, as evidenced by the significant textual overlap. Excluding Mark was not an option, given its historical and literary significance. Placing Mark second in the canonical order, after Matthew’s comprehensive narrative, masks any perceived shortcomings of Mark’s ending, allowing readers to encounter Matthew’s resurrection appearances first and thus harmonize the accounts. This positioning may suggest anxiety around Mark’s rhetorical style before the canon was formalized. Note on canonization: It did not occur at the Council of Nicaea as popularly believed, or at any other specific event. The Synod of Hippo in 393 addressed canon directly, but much earlier manuscripts show the modern ordering of books.

One other bit of housekeeping is worth noting here. The debates regarding Markan synthesis and scriptural construction – the claim that the Gospel of Mark constructs its Jesus narrative solely from Old Testament texts – is interesting but tangential to examining Mark’s rhetorical approach. Mark uses OT scripture to narrate meaning, regardless of whether its author was writing history or inventing fiction. He’s producing sacred narrative in a form recognizable to his audience. To narrate meaningfully was to echo scripture. Whether Mark saw the parallels as a signal of divine orchestration (fulfilment of prophecy, loosely) or solely as a literary device doesn’t matter. Mark likely courted that ambiguity like many others in his gospel.

I will argue that Mark is the most strategically self-effacing writer in early Christian literature, canonical or otherwise, hiding his own brilliance so you can experience something mysterious. He hides his craft by separating Mark the author from Mark the narrator, who seems slightly puzzled and slow, so that the reader can outpace the story itself. Differentiating author from narrator is the realm of reader-response criticism.

Coming next: What Is Reader Response Criticism?

Six Days to Failure? A Case Study in Cave Bolt Fatigue

Posted by Bill Storage in Engineering & Applied Physics on July 17, 2025

The terms fatigue failure and stress-corrosion cracking get tossed around in climbing and caving circles, often in ways that would make an engineer or metallurgist cringe. This is an investigation of a bolt failure in a cave that really was fatigue.

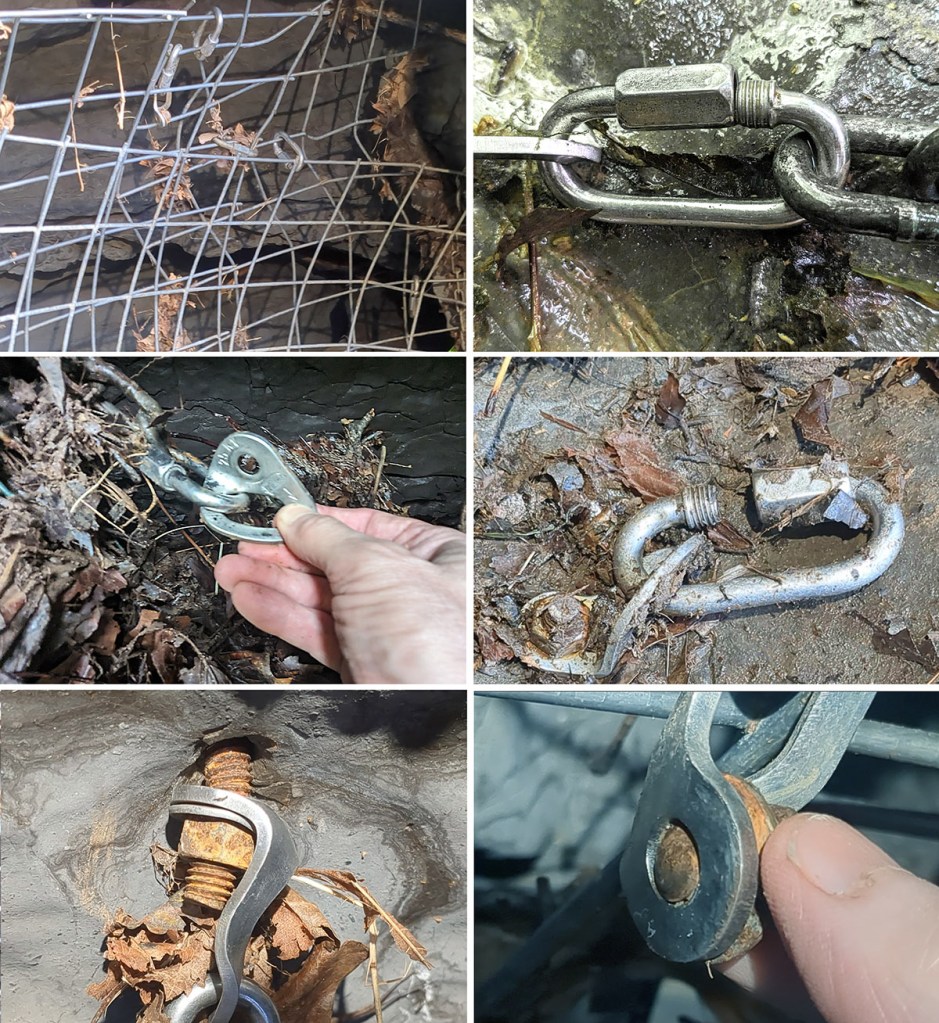

In October, we built a sort of gate to keep large stream debris from jamming the entrance to West Virginia’s Chestnut Ridge Cave. After placing 35 bolts – 3/8 by 3.5-inch, 304 stainless – we ran out. We then placed ten Confast zinc-plated mild steel wedge anchors of the same size. All nuts were torqued to between 20 and 30 foot-pounds.

The gate itself consisted of vertical chains from floor to ceiling, with several horizontal strands. Three layers of 4×4-inch goat panel were mounted upstream of the chains and secured using a mix of 304 stainless quick links and 316 stainless carabiners.

No one visited the entrance from November to July. When I returned in early July and peeled back layers of matted leaves, it was clear the gate had failed. One of the non-stainless bolts had fractured. Another had pulled out about half an inch and was bent nearly 20 degrees. Two other nuts had loosened and were missing. At least four quick links had opened enough to release chain or goat panel rods. Even pairs of carabiners with opposed gates had both opened, freeing whatever they’d been holding.

I recovered the hanger-end of the broken bolt and was surprised to see a fracture surface nearly perpendicular to the bolt’s axis, clearly not a shear break. The plane was flat and relatively smooth, with no sign of necking or the cup-and-cone profile typical of ductile tensile failure. Under magnification, the surface showed slight bumpiness, indicating the smoothness didn’t come from rubbing against the embedded remnant of the bolt. These features rule out a classic shear failure from preload loss (e.g., a nut loosening from vibration) and also rule out simple tensile overload and ductile fracture.

That leaves two possibilities: brittle tensile fracture or fatigue failure under higher-than-expected cyclic tensile load. Brittle fracture seems highly unlikely. Two potential causes exist. One is hydrogen embrittlement, but that’s rare in the low-strength carbon steel used in these bolts. The zinc-plating process likely involved acid cleaning and electroplating, which can introduce hydrogen. But this type of mild steel (probably Grade 2) is far too soft to trap it. Only if the bolt had been severely cold-worked or improperly baked post-plating would embrittlement be plausible.

The second possibility is a gross manufacturing defect or overhardening. That also seems improbable. Confast is a reputable supplier producing these bolts in massive quantities. The manufacturing process is simple, and I found no recall notices or defect reports. Hardness tests on the broken bolt (HRB ~90) confirm proper manufacturing and further suggest embrittlement wasn’t a factor.

While the available hydraulic energy at the cave entrance would seem to be low, and the 8-month time to failure is short, tensile fatigue originating at a corrosion pit emerges as the only remaining option. Its viability is supported by the partially pulled-out and bent bolt, which was placed about a foot away.

The broken bolt remained flush with the hanger, and the fracture lies roughly one hanger thickness from the nut. While the nut hadn’t backed off significantly, it had loosened enough to lose all preload. This left the bolt vulnerable to cyclic tensile loading from the attached chain vibrating in flowing water and from impacts by logs or boulders.

A fatigue crack could have initiated at a corrosion pit. Classic stress-corrosion cracking is rare in low-strength steel, but zinc-plated bolts under tension in corrosive environments sometimes behave unpredictably. The stream entering the cave has a summer pH of 4.6 to 5.0, but during winter, acidic conditions likely intensified, driven by leaf litter decay and the oxidation of pyrites in upstream Mauch Chunk shales after last year’s drought. The bolt’s initial preload would have imposed tensile stresses at 60–80% of yield strength. In that environment, stress-corrosion cracking is at least plausible.

More likely, though, preload was lost early due to vibration, and corrosion initiated a pit where the zinc plating had failed. The crack appears to have originated at the thread root (bottom right in above photo) and propagated across about two-thirds of the cross-section before sudden fracture occurred at the remaining ligament (top left).

The tensile stress area for 3/8 x 16 bolt would be 0.0775 square inches. If 65% was removed by fatigue, the remaining area would be 0.0271 sq. in. Assuming the final overload occurred at a tensile stress of around 60 ksi (SAE J429 Grade 2 bolts), then the final rupture would have required a tensile load of about 1600 pounds, a plausible value for a single jolt from a moving log or sudden boulder impact, especially given the force multiplier effect of the gate geometry, discussed below.

In mild steel, fatigue cracks can propagate under stress ranges as low as 10 to 30 percent of ultimate tensile strength, given a high enough number of cycles. Based on published S–N curves for similar material, we can sketch a basic relationship between stress amplitude and cycles to failure in an idealized steel rod (see columns 1 and 2 below).

Real-world conditions, of course, require adjustments. Threaded regions act as stress risers. Standard references assign a stress concentration factor (Kₜ) of about 3 to 4 for threads, which effectively lowers the endurance limit by roughly 40 percent. That brings the endurance limit down to around 7.5 ksi.

Surface defects from zinc plating and additional concentration at corrosion pits likely reduce it by another 10 percent. Adjusted stress levels for each cycle range are shown in column 3.

Does this match what we saw at the cave gate? If we assume the chain and fencing vibrated at around 2 Hz during periods of strong flow – a reasonable estimate based on turbulence – we get about 172,000 cycles per day. Just six days of sustained high flow would yield over a million cycles, corresponding to a stress amplitude of roughly 7 ksi based on adjusted fatigue data.

Given the bolt’s original cross-sectional area of 0.0775 in², a 7 ksi stress would require a cyclic tensile load of about 540 pounds.

| Cycles to Failure | Stress amplitude (ksi) | Adjusted Stress |

| ~10³ | 40 ksi | 30 ksi |

| ~10⁴ | 30 ksi | 20 ksi |

| ~10⁵ | 20 ksi | 12 ksi |

| ~10⁶ | 15 ksi | 7 ksi |

| Endurance limit | 12 ksi | 5 ksi |

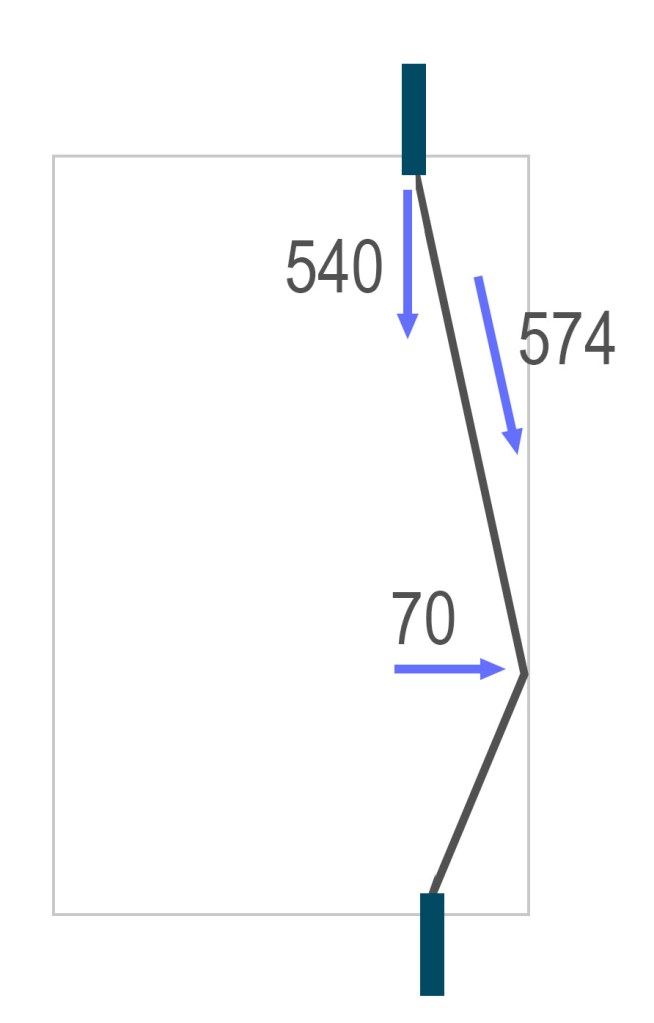

Could our gate setup impose 540-pound axial loads on ceiling bolts? Easily – and the geometry shows how. In load-bearing systems like the so-called “death triangle,” force multiplication depends on the angle between anchor points. This isn’t magic. It’s just static equilibrium: if an object is at rest, the vector sum of forces acting on it in every direction must be zero (as derived from Newton’s first two laws of mechanics).

In our case, if the chain between two vertically aligned bolts sags at a 20-degree angle, the axial force on each bolt is multiplied by about a factor of eight. That means a horizontal force of just 70 pounds – say, from a bouncing log – can produce an axial load (vertical load on the bolt) of 540 pounds.

Under the conditions described above, six days of such cycling would be enough to trigger fatigue failure at one million cycles. If a 100-pound force was applied instead, the number of cycles to failure would drop to around 100,000.

The result was genuinely surprising. I knew the principles, but I hadn’t expected fatigue at such low stress levels and with so few cycles. Yet the evidence is clear. The nearby bolt that pulled partly out likely saw axial loads of over 1,100 pounds, enough to cause failure in just tens of thousands of cycles had the broken bolt been in its place. The final fracture area on the failed bolt suggests a sudden tensile load of around 1,600 pounds. These numbers confirm that the gate was experiencing higher axial forces on bolts than we’d anticipated.

The root cause was likely a corrosion pit, inevitable in this setting, and something stainless bolts (304 or 316) would have prevented, though stainless wouldn’t have stopped pullout. Loctite might help quick links resist opening under impact and vibration, though that’s unproven in this context. Chains, while easy to rig, amplified axial loads due to their geometry and flexibility. Stainless cable might vibrate less in water. Unfortunately, surface conditions at the entrance make a rigid or welded gate impractical. Stronger bolts – ½ or even ⅝ inch – torqued to 55 to 85 foot-pounds may be the only realistic improvement, though installation will be a challenge in that setting.

More broadly, this case illustrates how quickly nature punishes the use of non-stainless anchors underground.

From Aqueducts to Algorithms: The Cost of Consensus

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science on July 9, 2025

The Scientific Revolution, we’re taught, began in the 17th century – a European eruption of testable theories, mathematical modeling, and empirical inquiry from Copernicus to Newton. Newton was the first scientist, or rather, the last magician, many historians say. That period undeniably transformed our understanding of nature.

Historians increasingly question whether a discrete “scientific revolution” ever happened. Floris Cohen called the label a straightjacket. It’s too simplistic to explain why modern science, defined as the pursuit of predictive, testable knowledge by way of theory and observation, emerged when and where it did. The search for “why then?” leads to Protestantism, capitalism, printing, discovered Greek texts, scholasticism, even weather. That’s mostly just post hoc theorizing.

Still, science clearly gained unprecedented momentum in early modern Europe. Why there? Why then? Good questions, but what I wonder, is why not earlier – even much earlier.

Europe had intellectual fireworks throughout the medieval period. In 1320, Jean Buridan nearly articulated inertia. His anticipation of Newton is uncanny, three centuries earlier:

“When a mover sets a body in motion he implants into it a certain impetus, that is, a certain force enabling a body to move in the direction in which the mover starts it, be it upwards, downwards, sidewards, or in a circle. The implanted impetus increases in the same ratio as the velocity. It is because of this impetus that a stone moves on after the thrower has ceased moving it. But because of the resistance of the air (and also because of the gravity of the stone) … the impetus will weaken all the time. Therefore the motion of the stone will be gradually slower, and finally the impetus is so diminished or destroyed that the gravity of the stone prevails and moves the stone towards its natural place.”

Robert Grosseteste, in 1220, proposed the experiment-theory iteration loop. In his commentary on Aristotle’s Posterior Analytics, he describes what he calls “resolution and composition”, a method of reasoning that moves from particulars to universals, then from universals back to particulars to make predictions. Crucially, he emphasizes that both phases require experimental verification.

In 1360, Nicole Oresme gave explicit medieval support for a rotating Earth:

“One cannot by any experience whatsoever demonstrate that the heavens … are moved with a diurnal motion… One can not see that truly it is the sky that is moving, since all movement is relative.”

He went on to say that the air moves with the Earth, so no wind results. He challenged astrologers:

“The heavens do not act on the intellect or will… which are superior to corporeal things and not subject to them.”

Even if one granted some influence of the stars on matter, Oresme wrote, their effects would be drowned out by terrestrial causes.

These were dead ends, it seems. Some blame the Black Death, but the plague left surprisingly few marks in the intellectual record. Despite mass mortality, history shows politics, war, and religion marching on. What waned was interest in reviving ancient learning. The cultural machinery required to keep the momentum going stalled. Critical, collaborative, self-correcting inquiry didn’t catch on.

A similar “almost” occurred in the Islamic world between the 10th and 16th centuries. Ali al-Qushji and al-Birjandi developed sophisticated models of planetary motion and even toyed with Earth’s rotation. A layperson would struggle to distinguish some of al-Birjandi’s thought experiments from Galileo’s. But despite a wealth of brilliant scholars, there were few institutions equipped or allowed to convert knowledge into power. The idea that observation could disprove theory or override inherited wisdom was socially and theologically unacceptable. That brings us to a less obvious candidate – ancient Rome.

Rome is famous for infrastructure – aqueducts, cranes, roads, concrete, and central heating – but not scientific theory. The usual story is that Roman thought was too practical, too hierarchical, uninterested in pure understanding.

One text complicates that story: De Architectura, a ten-volume treatise by Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, written during the reign of Augustus. Often described as a manual for builders, De Architectura is far more than a how-to. It is a theoretical framework for knowledge, part engineering handbook, part philosophy of science.

Vitruvius was no scientist, but his ideas come astonishingly close to the scientific method. He describes devices like the Archimedean screw or the aeolipile, a primitive steam engine. He discusses acoustics in theater design, and a cosmological models passed down from the Greeks. He seems to describe vanishing point perspective, something seen in some Roman art of his day. Most importantly, he insists on a synthesis of theory, mathematics, and practice as the foundation of engineering. His describes something remarkably similar to what we now call science:

“The engineer should be equipped with knowledge of many branches of study and varied kinds of learning… This knowledge is the child of practice and theory. Practice is the continuous and regular exercise of employment… according to the design of a drawing. Theory, on the other hand, is the ability to demonstrate and explain the productions of dexterity on the principles of proportion…”

“Engineers who have aimed at acquiring manual skill without scholarship have never been able to reach a position of authority… while those who relied only upon theories and scholarship were obviously hunting the shadow, not the substance. But those who have a thorough knowledge of both… have the sooner attained their object and carried authority with them.”

This is more than just a plea for well-rounded education. H e gives a blueprint for a systematic, testable, collaborative knowledge-making enterprise. If Vitruvius and his peers glimpsed the scientific method, why didn’t Rome take the next step?

The intellectual capacity was clearly there. And Roman engineers, like their later European successors, had real technological success. The problem, it seems, was societal receptiveness.

Science, as Thomas Kuhn famously brough to our attention, is a social institution. It requires the belief that man-made knowledge can displace received wisdom. It depends on openness to revision, structured dissent, and collaborative verification. These were values that the Roman elite culture distrusted.

When Vitruvius was writing, Rome had just emerged from a century of brutal civil war. The Senate and Augustus were engaged in consolidating power, not questioning assumptions. Innovation, especially social innovation, was feared. In a political culture that prized stability, hierarchy, and tradition, the idea that empirical discovery could drive change likely felt dangerous.

We see this in Cicero’s conservative rhetoric, in Seneca’s moralism, and in the correspondence between Pliny and Trajan, where even mild experimentation could be viewed as subversive. The Romans could build aqueducts, but they wouldn’t fund a lab.

Like the Islamic world centuries later, Rome had scholars but not systems. Knowledge existed, but the scaffolding to turn it into science – collective inquiry, reproducibility, peer review, invitations for skeptics to refute – never emerged.

Vitruvius’s De Architectura deserves more attention, not just as a technical manual but as a proto-scientific document. It suggests that the core ideas behind science were not exclusive to early modern Europe. They’ve flickered into existence before, in Alexandria, Baghdad, Paris, and Rome, only to be extinguished by lack of institutional fit.

That science finally took root in the 17th century had less to do with discovery than with a shift in what society was willing to do with discovery. The real revolution wasn’t in Newton’s laboratory, it was in the culture.

Rome’s Modern Echo?

It’s worth asking whether we’re becoming more Roman ourselves. Today, we have massively resourced research institutions, global scientific networks, and generations of accumulated knowledge. Yet, in some domains, science feels oddly stagnant or brittle. Dissenting views are not always engaged but dismissed, not for lack of evidence, but for failing to fit a prevailing narrative.

We face a serious, maybe existential question. Does increasing ideological conformity, especially in academia, foster or hamper science?

Obviously, some level of consensus is essential. Without shared standards, peer review collapses. Climate models, particle accelerators, and epidemiological studies rely on a staggering degree of cooperation and shared assumptions. Consensus can be a hard-won product of good science. And it can run perilously close to dogma. In the past twenty years we’ve seen consensus increasingly enforced by legal action, funding monopolies, and institutional ostracism.

String theory may (or may not) be physics’ great white whale. It’s mathematically exquisite but empirically elusive. For decades, critics like Lee Smolin and Peter Woit have argued that string theory has enjoyed a monopoly on prestige and funding while producing little testable output. Dissenters are often marginalized.

Climate science is solidly evidence-based, but responsible scientists point to constant revision of old evidence. Critics like Judith Curry or Roger Pielke Jr. have raised methodological or interpretive concerns, only to find themselves publicly attacked or professionally sidelined. Their critique is labeled denial. Scientific American called Curry a heretic. Lawsuits, like Michael Mann’s long battle with critics, further signal a shift from scientific to pre-scientific modes of settling disagreement.

Jonathan Haidt, Lee Jussim, and others have documented the sharp political skew of academia, particularly in the humanities and social sciences, but increasingly in hard sciences too. When certain political assumptions are so embedded, they become invisible. Dissent is called heresy in an academic monoculture. This constrains the range of questions scientists are willing to ask, a problem that affects both research and teaching. If the only people allowed to judge your work must first agree with your premises, then peer review becomes a mechanism of consensus enforcement, not knowledge validation.

When Paul Feyerabend argued that “the separation of science and state” might be as important as the separation of church and state, he was pushing back against conservative technocratic arrogance. Ironically, his call for epistemic anarchism now resonates more with critics on the right than the left. Feyerabend warned that uniformity in science, enforced by centralized control, stifles creativity and detaches science from democratic oversight.

Today, science and the state, including state-adjacent institutions like universities, are deeply entangled. Funding decisions, hiring, and even allowable questions are influenced by ideology. This alignment with prevailing norms creates a kind of soft theocracy of expert opinion.

The process by which scientific knowledge is validated must be protected from both politicization and monopolization, whether that comes from the state, the market, or a cultural elite.

Science is only self-correcting if its institutions are structured to allow correction. That means tolerating dissent, funding competing views, and resisting the urge to litigate rather than debate. If Vitruvius teaches us anything, it’s that knowing how science works is not enough. Rome had theory, math, and experimentation. What it lacked was a social system that could tolerate what those tools would eventually uncover. We do not yet lack that system, but we are testing the limits.

Rational Atrocity?

Posted by Bill Storage in Probability and Risk on July 4, 2025

Bayesian Risk and the Internment of Japanese Americans

We can use Bayes (see previous post) to model the US government’s decision to incarcerate Japanese Americans, 80,000 of which were US citizens, to reduce a perceived security risk. We can then use a quantified risk model to evaluate the internment decision.

We define two primary hypotheses regarding the loyalty of Japanese Americans:

- H1: The population of Japanese Americans are generally loyal to the United States and collectively pose no significant security threat.

- H2: The population of Japanese Americans poses a significant security threat (e.g., potential for espionage or sabotage).

The decision to incarceration Japanese Americans reflects policymakers’ belief in H2 over H1, updated based on evidence like the Niihau Incident.

Prior Probabilities

Before the Niihau Incident, policymakers’ priors were influenced by several factors:

- Historical Context: Anti-Asian sentiment on the West Coast, including the 1907 Gentlemen’s Agreement and 1924 Immigration Act, fostered distrust of Japanese Americans.

- Pearl Harbor: The surprise attack on December 7, 1941, heightened fears of internal threats. No prior evidence of disloyalty existed.

- Lack of Data: No acts of sabotage or espionage by Japanese Americans had been documented before Niihau. Espionage detection and surveillance were limited. Several espionage rings tied to Japanese nationals were active (Itaru Tachibana, Takeo Yoshikawa).

Given this, we can estimate subjective priors:

- P(H1) = 0.99: Policymakers might have initially been 99 percent confident that Japanese Americans were loyal, as they were U.S. citizens or long-term residents with no prior evidence of disloyalty. The pre-Pearl Harbor Munson Report (“There is no Japanese `problem’ on the Coast”) supported this belief.

- P(H2) = 0.01: A minority probability of threat due to racial prejudices, fear of “fifth column” activities, and Japan’s aggression.

These priors are subjective and reflect the mix of rational assessment and bias prevalent at the time. Bayesian reasoning (Subjective Bayes) requires such subjective starting points, which are sometimes critical to the outcome.

Evidence and Likelihoods

The key evidence influencing the internment decision was the Niihau Incident (E1) modeled in my previous post. We focus on this, as it was explicitly cited in justifying internment, though other factors (e.g., other Pearl Harbor details, intelligence reports) played a role.

E1: The Niihau Incident

Yoshio and Irene Harada, Nisei residents, aided Nishikaichi in attempting to destroy his plane, burn papers, and take hostages. This was interpreted by some (e.g., Lt. C.B. Baldwin in a Navy report) as evidence that Japanese Americans might side with Japan in a crisis.

Likelihoods:

P(E1|H1) = 0.01: If Japanese Americans are generally loyal, the likelihood of two individuals aiding an enemy pilot is low. The Haradas’ actions could be seen as an outlier, driven by personal or situational factors (e.g., coercion, cultural affinity). Note that this 1% probability is not the same 1% probability of H1, the prior belief that Japanese Americans weren’t loyal. Instead, P(E1|H1) is the likelihood assigned to whether E1, the Harada event, would have occurred given than Japanese Americans were loyal to the US.

P(E1|H2) = 0.6: High likelihood of observing the Harada evidence if the population of Japanese Americans posed a threat.

Posterior Calculation Using Bayes Theorem:

P(H1∣E1) = P(E1∣H1)⋅P(H1) / [P(E1∣H1)⋅P(H1)+P(E1∣H2)⋅P(H2)]

P(H1∣E1)=0.01⋅0.99 / [(0.01⋅0.99)+(0.6⋅0.01)] = 0.626

P(H2|E1) = 1 – P(H1|E1) = 0.374

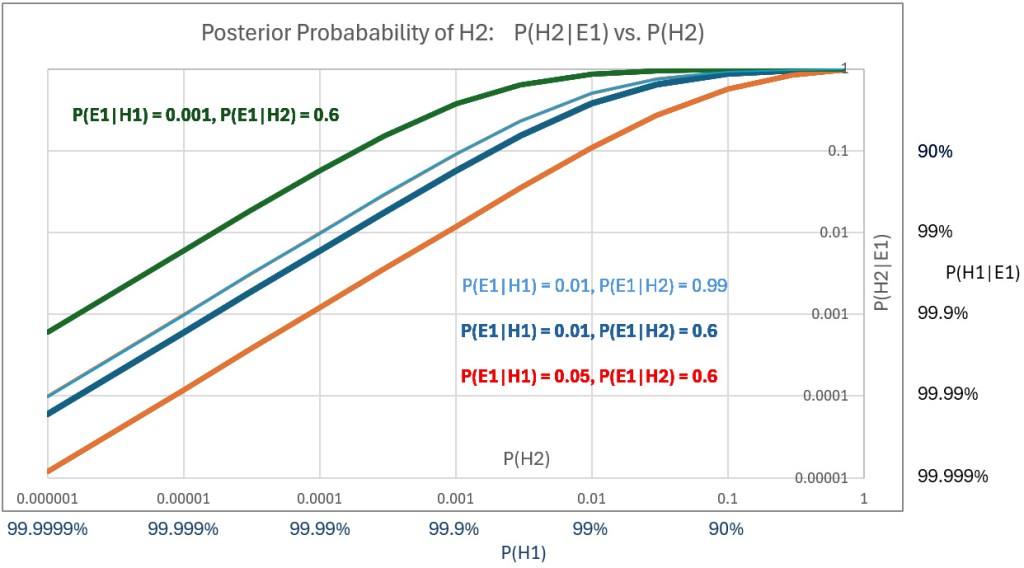

The Niihau Incident significantly increases the probability of H2 (its prior was 0.01), suggesting a high perceived threat. This aligns with the heightened alarm in military and government circles post-Niihau. 62.6% confidence in loyalty is unacceptable by any standards. We should experiment with different priors.

Uncertainty Quantification

- Aleatoric Uncertainty: The Niihau Incident involved only two people.

- Epistemic Uncertainty: Prejudices and wartime fear would amplify P(H2).

Sensitivity to P(H1)

The posterior probability of H2 is highly sensitive to changes in P(H2) – and to P(H1) because they are linearly related: P(H2) = 1.0 – P(H1).

The posterior probability of H2 is somewhat sensitive to the likelihood assigned to P(E1|H1), but in a way that may be counterintuitive – because it is the likelihood assigned to whether E1, the Harada event, would have occurred given than Japanese Americans were loyal. We now know them to have been loyal, but that knowledge can’t be used in this analysis. Increasing this value lowers the posterior probability.

The posterior probability of H2 is relatively insensitive to changes in P(E1|H2), the likelihood of observing the evidence if Japanese Americans posed a threat (which, again, we now know them to have not).

A plot of posterior probability of H2 against the prior probabilities assigned to H2 – that is, P(H2|E1) vs P(H2) – for a range of values of P(H2) using three different values of P(E1|H1) shows the sensitivities. The below plot (scales are log-log) also shows the effect of varying P(E1|H2); compare the thin blue line to the thick blue line.

Prior hypotheses with probabilities greater the 99% represent confidence levels that are rarely justified. Nevertheless, we plot high posteriors for priors of H1 (i.e., posteriors of H2 down to 0.00001 (1E-5). Using P(E1|H1) = 0.05 and P(E1|H2 = 0.6, we get a posterior P(H2|E1) = 0.0001 – or P(H1|E1) = 99.99%, which might be initially judged as not supporting incarceration of US citizens in what were effectively concentration camps.

Risk

While there is no evidence of either explicit Bayesian reasoning or risk quantification by Franklin D. Roosevelt or military analysts, we can examine their decisions using reasonable ranges of numerical values that would have been used if numerical analysis had been employed.

We can model risk, as is common in military analysis, by defining it as the product of severity and probability – probability equal to that calculated as the posterior probability that a threat existed in the population of 120,000 who were interned.

Having established a range of probabilities for threat events above, we can now estimate severity – the cost of a loss – based on lost lives and lost defense capability resulting from a threat brought to life.

The Pearl Harbor attack itself tells us what a potential hazard might look like. Eight U.S. Navy battleships were at Pearl Harbor: Arizona, Oklahoma, West Virginia, California, Nevada, Tennessee, Maryland, and Pennsylvania. Typical peacetime crew sizes ranged from 1,200 to 1,500 per battleship, though wartime complements could exceed that. About 8,000–10,000 sailors were assigned to the battleships. More sailors would have been on board had the attack not happened on a Sunday morning.

About 37,000 Navy and 14,000 Army personnel were stationed at Pearl Harbor. 2,403 were killed in the attack, most of them aboard battleships. Four battleships were sunk. The Arizona suffered a catastrophic magazine explosion from a direct bomb hit. Over 1,170 crew members were killed. 400 were killed on the Oklahoma when it sank. None of the three aircraft carriers of the Pacific Fleet were in Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7. The USS Enterprise was due to be in port on Dec. 6 but was delayed by weather. Its crew was about 2,300 men.

Had circumstances differed slightly, the attack would not have been a surprise, and casualties would have been fewer. But in other conceivable turns of events, they could have been far greater. A modern impact analysis of an attack on Pearl Harbor or other bases would consider an invasion’s “cost” to be 10 to 20,000 lives and the loss of defense capability due to destroyed ships and aircraft. Better weather could have meant destruction of one third of US aircraft carriers in the Pacific.

Using a linear risk model, an analyst, if such analysis was done back then, might have used the above calculated P(H2|E1) as the probability of loss and 10,000 lives as one cost of the espionage. Using probability P(H1) in the range of 99.99% confidence in loyalty – i.e., P(H2) = 1E-4 – and severity = 10,000 lives yields quantified risk.

As a 1941 risk analyst, you would be considering a one-in-10,000 chance of losing 10,000 lives and loss of maybe 25% of US defense capacity. Another view of the risk would be that each of 120,000 Japanese Americans poses a one-in-10,000 chance of causing 10,000 deaths, an expected cost of roughly 120,000 lives (roughly, because the math isn’t quite as direct as it looks in this example).

While I’ve modeled the decision using a linear expected value approach, it’s important to note that real-world policy, especially in safety-critical domains, is rarely risk-neutral. For instance, Federal Aviation Regulation AC 25.1309 states that “no single failure, regardless of probability, shall result in a catastrophic condition”, a clear example of a threshold risk model overriding probabilistic reasoning. In national defense or public safety, similar thinking applies. A leader might deem a one-in-10,000 chance of catastrophic loss (say, 10,000 deaths and 25% loss of Pacific Fleet capability) intolerable, even if the expected value (loss) were only one life. This is not strictly about math; it reflects public psychology and political reality. A risk-averse or ambiguity-intolerant government could rationally act under such assumptions.

Would you take that risk, or would you incarcerate? Would your answer change if you used P(H1) = 99.999 percent? Could a prior of that magnitude ever be justified?

From the perspective of quantified risk analysis (as laid out in documents like FAR AC 25.1309), President Roosevelt, acting in early 1942 would have been justified even if P(H1) had been 99.999%.

In a society so loudly committed to consequentialist reasoning, this choice ought to seem defensible. That it doesn’t may reveal more about our moral bookkeeping than about Roosevelt’s logic. Racism existed in California in 1941, but it unlikely increased scrutiny by spy watchers. The fact that prejudice existed does not bear on the decision, because the prejudice did not motivate any action that would have born – beyond the Munson Report – on the prior probabilities used. That the Japanese Americans were held far too long is irrelevant to Roosevelt’s decision.

Since the rationality of Roosevelt’s decision, as modeled by Bayesian reasoning and quantified risk, ultimately hinges on P(H1), and since H1’s primary input was the Munson Report, we might scrutinize the way the Munson Report informs H1.

The Munson Report is often summarized with its most quoted line: “There is no Japanese ‘problem’ on the Coast.” And that was indeed its primary conclusion. Munson found Japanese American citizens broadly loyal and recommended against mass incarceration. However, if we assume the report to be wholly credible – our only source of empirical grounding at the time – then certain passages remain relevant for establishing a prior. Munson warned of possible sabotage by Japanese nationals and acknowledged the existence of a few “fanatical” individuals willing to act violently on Japan’s behalf. He recommended federal control over Japanese-owned property and proposed using loyal Nisei to monitor potentially disloyal relatives. These were not the report’s focus, but they were part of it. Critics often accuse John Franklin Carter of distorting Munson’s message when advising Roosevelt. Carter’s motives are beside the point. Whether his selective quotations were the product of prejudice or caution, the statements he cited were in the report. Even if we accept Munson’s assessment in full – affirming the loyalty of Japanese American citizens and acknowledging only rare threats – the two qualifiers Carter cited are enough to undercut extreme confidence. In modern Bayesian practice, priors above 99.999% are virtually unheard of, even in high-certainty domains like particle physics and medical diagnostics. From a decision-theoretic standpoint, Munson’s own language renders such priors unjustifiable. With confidence lower than that, Roosevelt made the rational decision – clear in its logic, devastating in its consequences.

Bayes Theorem, Pearl Harbor, and the Niihau Incident

Posted by Bill Storage in Probability and Risk on July 2, 2025

The Niihau Incident of December 7–13, 1941 provides a good case study for applying Bayesian reasoning to historical events, particularly in assessing decision-making under uncertainty. Bayesian reasoning involves updating probabilities based on new evidence, using Bayes’ theorem: P(A∣B) = P(B∣A) ⋅ P(A)P(B) / P(A|B), where:

- P(E∣H) is the likelihood of observing E given H

- P(H∣E) is the posterior probability of hypothesis H given evidence E

- P(H) is the prior probability of H

- P(E) is the marginal probability of E.

Terms like P(E∣H), the probability of evidence given a hypothesis, can be confusing. Alternative phrasings may help:

- The probability of observing evidence E if hypothesis H were true

- The likelihood of E given H

- The conditional probability of E under H

These variations clarify that we’re assessing how likely the evidence is under a specific scenario, not the probability of the hypothesis itself, which is P(H∣E).

In the context of the Niihau Incident, we can use Bayesian reasoning to analyze the decisions made by the island’s residents, particularly the Native Hawaiians and the Harada family, in response to the crash-landing of Japanese pilot Shigenori Nishikaichi. Below, I’ll break down the analysis, focusing on key decisions and quantifying probabilities while acknowledging the limitations of historical data.

Context of the Niihau Incident

On December 7, 1941, after participating in the Pearl Harbor attack, Japanese pilot Shigenori Nishikaichi crash-landed his damaged A6M2 Zero aircraft on Niihau, a privately owned Hawaiian island with a population of 136, mostly Native Hawaiians. The Japanese Navy had mistakenly designated Niihau as an uninhabited island for emergency landings, expecting pilots to await rescue there. The residents, unaware of the Pearl Harbor attack, initially treated Nishikaichi as a guest but confiscating his weapons. Over the next few days, tensions escalated as Nishikaichi, with the help of Yoshio Harada and his wife Irene, attempted to destroy his plane and papers, took hostages, and engaged in violence. The incident culminated in the Kanaheles, a Hawaiian couple, overpowering and killing Nishikaichi. Yoshio Harada committing suicide.

From a Bayesian perspective, we can analyze the residents updating their beliefs as new evidence emerged.

We define two primary hypotheses regarding Nishikaichi’s intentions:

- H1: Nishikaichi is a neutral (non-threatening) lost pilot needing assistance.

- H2: Nishikaichi is an enemy combatant with hostile intentions.

The residents’ decisions reflect the updating of beliefs about (credence in) these hypotheses.

Prior Probabilities

At the outset, the residents had no knowledge of the Pearl Harbor attack. Thus, their prior probability for P(H1) (Nishikaichi is non-threatening) would likely be high, as a crash-landed pilot could reasonably be seen as a distressed individual. Conversely, P(H2) (Nishikaichi is a threat) would be low due to the lack of context about the war.

We can assign initial priors based on this context:

- P(H1) = 0.9: The residents initially assume Nishikaichi is a non-threatening guest, given their cultural emphasis on hospitality and lack of information about the attack.

- P(H2) = 0.1: The possibility of hostility exists but is less likely without evidence of war.

These priors are subjective, reflecting the residents’ initial state of knowledge, consistent with the Bayesian interpretation of probability as a degree of belief.

We identify key pieces of evidence that influenced the residents’ beliefs:

E1: Nishikaichi’s Crash-Landing and Initial Behavior

Nishikaichi crash-landed in a field near Hawila Kaleohano, who disarmed him and treated him as a guest. His initial behavior (not hostile) supports H1.

Likelihoods:

- P(E1∣H1) = 0.95: A non-threatening pilot is highly likely to crash-land and appear cooperative.

- P(E1∣H2) = 0.3: A hostile pilot could be expected to act more aggressively, though deception is possible.

Posterior Calculation:

P(H1∣E1) = [P(E1∣H1)⋅P(H1)] / [P(E1∣H1)⋅P(H1) + P(E1∣H2)⋅P(H2) ]

P(H1|E1) = 0.95⋅0.9 / [(0.95⋅0.9) + (0.3⋅0.1)] = 0.97

After the crash, the residents’ belief in H1 justifies hospitality.

E2: News of the Pearl Harbor Attack

That night, the residents learned of the Pearl Harbor attack via radio, revealing Japan’s aggression. This significantly increases the likelihood that Nishikaichi was a threat.

Likelihoods:

- P(E2∣H1) = 0.1 P(E2|H1) = 0.1 P(E2∣H1) = 0.1: A non-threatening pilot is unlikely to be associated with a surprise attack.

- P(E2∣H2) = 0.9 P(E2|H2) = 0.9 P(E2∣H2) = 0.9: A hostile pilot is highly likely to be linked to the attack.

Posterior Calculation (using updated priors from E1):

P(H1∣E2) = P(E2∣H1)⋅P(H1∣E1) / [P(E2∣H1)⋅P(H1∣E1) + P(E2∣H2)⋅P(H2∣E1)]

P(H1∣E2) = 0.1⋅0.97 / [(0.1⋅0.97) + (0.9⋅0.03)] = 0.76

P(H2∣E2) = 0.24

The news shifts the probability toward H2, prompting the residents to apprehend Nishikaichi and put him under guard with the Haradas.

E3: Nishikaichi’s Collusion with the Haradas

Nishikaichi convinced Yoshio and Irene Harada to help him escape, destroy his plane, and burn Kaleohano’s house to eliminate his papers.

Likelihoods:

- P(E3∣H1) = 0.01: A non-threatening pilot is extremely unlikely to do this.

- P(E3∣H2) = 0.95: A hostile pilot is likely to attempt to destroy evidence and escape.

Posterior Calculation (using updated priors from E2):

P(H1∣E3) = P(E3∣H1)⋅P(H1∣E2) / [P(E3∣H1)⋅P(H1∣E2) + P(E3∣H2)⋅P(H2∣E2)]

P(H1∣E3) = 0.01⋅0.759 / [(0.01⋅0.759) + (0.95⋅0.241)] = 0.032

P(H2∣E3) = 0.968

This evidence dramatically increases the probability of H2, aligning with the residents’ decision to confront Nishikaichi.

E4: Nishikaichi Takes Hostages and Engages in Violence

Nishikaichi and Harada took Ben and Ella Kanahele hostage, and Nishikaichi fired a machine gun. Hostile intent is confirmed.

Likelihoods:

- P(E4∣H1) = 0.001: A non-threatening pilot is virtually certain not to take hostages or use weapons.

- P(E4∣H2) = 0.99: A hostile pilot is extremely likely to resort to violence.

Posterior Calculation (using updated priors from E3):

P(H1∣E4) = P(E4∣H1)⋅P(H1∣E3)/ [P(E4∣H1)⋅P(H1∣E3) + P(E4∣H2)⋅P(H2∣E3)P(H1|E4)]

P(H1∣E4) = 0.001⋅0.032 / [(0.001⋅0.032)+(0.99⋅0.968)] =0.00003

P(H2∣E4) = 1.0 – P(H1∣E4) = 0.99997

At this point, the residents’ belief in H2 is near certainty, justifying the Kanaheles’ decisive action to overpower Nishikaichi.

Uncertainty Quantification

Bayesian reasoning also involves quantifying uncertainty, particularly aleatoric (inherent randomness) and epistemic (model uncertainty) components.

Aleatoric Uncertainty: The randomness in Nishikaichi’s actions (e.g., whether he would escalate to violence) was initially high due to the residents’ lack of context. As evidence accumulated, this uncertainty decreased, as seen in the near-certain posterior for H2 after E4.

Epistemic Uncertainty: The residents’ model of Nishikaichi’s intentions was initially flawed due to their isolation and lack of knowledge about the war. This uncertainty reduced as they incorporated news of Pearl Harbor and observed Nishikaichi’s actions, refining their model of his behavior.

Analysis of Decision-Making

The residents’ actions align with Bayesian updating:

Initial Hospitality (E1): High prior for H1 led to treating Nishikaichi as a guest, with precautions (disarming him) reflecting slight uncertainty.

Apprehension (E2): News of Pearl Harbor shifted probabilities toward H2, prompting guards and confinement with the Haradas.

Confrontations (E3, E4): Nishikaichi’s hostile actions (collusion, hostage-taking) pushed P(H2) to near 1, leading to the Kanaheles’ lethal response.

The Haradas’ decision to assist Nishikaichi complicates the analysis. Their priors may have been influenced by cultural or personal ties to Japan, increasing their P(H1) or introducing a separate hypothesis of loyalty to Japan. Lack of detailed psychological data makes quantifying their reasoning speculative.

Limitations and Assumptions

Subjective Priors: The assigned priors (e.g., P(H1) = 0.9) are estimates based on historical context, not precise measurements. Bayesian reasoning allows subjective priors, but different assumptions could alter results.

Likelihood Estimates: Likelihoods (e.g., P(E1∣H1) = 0.95) are informed guesses, as historical records lack data on residents’ perceptions.

Simplified Hypotheses: I used two hypotheses for simplicity. In reality, residents may have considered nuanced possibilities, e.g., Nishikaichi being coerced or acting out of desperation.

Historical Bias: may exaggerate or omit details, affecting our understanding of evidence.

Conclusion

Bayesian reasoning (Subjective Bayes) provides a structured framework to understand how Niihau’s residents updated their beliefs about Nishikaichi’s intentions. Initially, a high prior for him being non-threatening (P(H1)=0.9) was reasonable given their isolation. As evidence accumulated (news of Pearl Harbor, Nishikaichi’s collusion with the Haradas, and his violent actions) the posterior probability of hostility, P(H2) approached certainty, justifying their escalating responses. Quantifying this process highlights the rationality of their decisions under uncertainty, despite limited information. This analysis demonstrates Bayesian inference used to model historical decision-making, assuming the deciders were rational agents.

Next

The Niihau Incident influenced U.S. policy decisions regarding the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. It heightened fears of disloyalty among Japanese Americans. Applying Bayesian reasoning to the decision to intern Japanese Americans after the Niihau Incident might provide insight on how policymakers updated their beliefs about the potential threat posed by this population based on limited evidence and priors. In a future post, I’ll use Bayes’ theorem to model this decision-making process to model the quantification of risk.

If the Good Lord’s Willing and the Creek Don’t Rise

Posted by Bill Storage in Commentary on June 30, 2025

Feller said don’t try writin dialect less you have a good ear. Now do I think my ear’s good? Well, I do and I don’t. Problem is, younguns ain’t mindin this store. I’m afeared we don’t get it down on paper we gonna lose it. So I went up the holler to ask Clare his mind on it.

We set a spell. He et his biscuits cold, sittin on the porch, not sayin’ much, piddlin with a pocketknife like he had a mind to whittle but couldn’t commit. Clare looked like sumpin the cat drug in. He was wore slap out from clearing the dreen so he don’t hafta tote firewood from up where the gator can’t git. “Reckon it’ll come up a cloud,” he allowed, squinting yonder at the ridge. “Might could,” I said. He nodded slow. “Don’t fret none,” he said. “That haint don’t stir in the holler less it’s fixin ta storm proper.” Then he leaned back, tuckered, fagged-out, and let the breeze do the talkin.

Now old Clare, he called it alright. Well, I’ll swan! The wind took up directly, then down it come. We watched the brown water push a wall of dead leaves and branches down yon valley. Dry Branch, they call it, and that’s a fact. Ain’t dry now. Feature it. One minute dry as dust, then come a gully-washer, bless yer heart. That was right smart of time ago.

If you got tolerable horse sense for Appalachian colloquialism, you’ll have understood most of that. A haint, by the way, is a spirit, a ghost, a spell, or a hex. Two terms used above make me wonder if all the technology we direct toward capturing our own shreds of actual American culture still fail to record these treasured regionalisms.

A “dreen,” according to Merriam-Webster, is “a dialectal variation of ‘drain,’ especially in Southern and South Midland American English.” Nah, not in West Virginia. That definition is a perfect example of how dictionaries flatten regional terms into their nearest Standard English cousin and, in doing so, miss the real story. It’s too broad and bland to capture what was, in practice, a topographic and occupational term used by loggers.

A dreen, down home, is a narrow, shallow but steep-sided and steeply sloping valley used to slide logs down. It’s recognized in local place-names and oral descriptions. Clear out the gully – the drain – for logs and you got yourself a dreen. The ravine’s water flow, combined with exposed shards of shale, make it slick. Drop logs off up top, catch them in a basin at the bottom. An economical means for moving logs down rough terrain without a second team of horses, specialized whiffletrees, and a slip-tongue skidder. How is it that there is zero record of what a dreen is on the web?

To “feature” something means to picture it in your mind. Like, “imagine,” but more concrete. “Picture this” + “feature picture” → “feature this.” Maybe? I found a handful of online forums where someone wrote, “I can’t feature it,” but the dictionaries are silent. What do I not pay you people for?

It’s not just words and phrases that our compulsive documentation and data ingestion have failed to capture about Appalachia. Its expressive traditions rarely survive the smooshing that comes with cinematic stereotypes. Poverty, moonshine, fiddles, a nerdy preacher and, more lately, mobile meth labs, are easy signals for “rural and backward.” Meanwhile, the texture of Appalachian life is left out.

Ever hear of shape-note music? How about lined-out singing? The style is raw and slow, not that polished gospel stuff you hear down in Alabama. The leader “lines out” a hymn, and the congregation follows in a full, droning response. It sounds like a mixture of Gaelic and plain chant – and probably is.

Hill witch. Granny women, often midwives, were herbalists and folk doctors. Their knowledge was empirical, intergenerational, and somehow female-owned. They were healers with an oral pharmacopoeia rooted in a mix of Native American and Scottish traditions. Hints of it, beyond the ginseng, still pop up here and there.

Jack tales. They pick up where Jack Frost, Jack and Jill, and Little Jack Horner left off. To my knowledge, those origins are completely unrelated to each other. Jack tales use these starting points to spin yarns about seemingly low-ambition or foolish folk who outfox them what think they’re smart. (Pronounce “smart” with a short “o” and a really long “r” that stretches itself into two distinct syllables.)

Now, I know that in most ways, none of that amounts to a hill of beans, but beyond the dialect, I fear we’re going to lose some novel expressions. Down home,

“You can’t get there from here” means it is metaphorically impossible or will require a lot of explaining.

“Puny” doesn’t mean you’re small; it means you look sick.

“That dog won’t hunt” means an idea, particularly a rebuttal or excuse, that isn’t plausible.

“Tighter than Dick’s hatband” means that someone is stingy or has proposed an unfair trade.

“Come day, go day, God send Sunday” means living day to day, e.g., hoping the drought lets up.

“He’s got the big eye” means he can’t sleep.

“He’s ate up with it” means he’s obsessed – could be jealousy, could be pride.

“Well, I do and I don’t” says more than indecision. You deliver it as a percussive anapest (da-da-DUM!, da-da-DUM!), granting it a kind of rhythmic, folksy authority. It’s a measured fence-sitting phrase that buys time while saying something real. It’s a compact way to acknowledge nuance, to say, “I agree… to a point,” followed with “It’s complicated…” Use it to acknowledge an issue as more personal and moral, less analytical. You can avoid full commitment while showing thoughtfulness. It weighs individual judgment. See also:

“There’s no pancake so thin it ain’t got two sides.”

The stoics got nothin on this baby. I don’t want you think I’m uppity – gettin above my raisin, I mean – but this one’s powerful subtle. There’s a conflict between principle and sympathy. It flattens disagreement by framing it as something natural. Its double negative ain’t no accident. Deploy it if you’re slightly cornered but not ready to concede. You acknowledge fairness, appear to hover above the matter at hand, seemingly without taking sides. Both parties know you have taken a side, of course. And that’s ok. That’s how we do it down here. This is de-escalation of conflict through folk epistemology: nothing is so simple that it doesn’t deserve a second look. Even a blind hog finds an acorn now and then. Just ‘cause the cat’s a-sittin still don’t mean it ain’t plannin.

Appalachia is America’s most misunderstood archive, its stories tucked away in hollers like songs no one’s sung for decades.

Grains of Truth: Science and Dietary Salt

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science, Philosophy of Science on June 29, 2025

Science doesn’t proceeds in straight lines. It meanders, collides, and battles over its big ideas. Thomas Kuhn’s view of science as cycles of settled consensus punctuated by disruptive challenges is a great way to understand this messiness, though later approaches, like Imre Lakatos’s structured research programs, Paul Feyerabend’s radical skepticism, and Bruno Latour’s focus on science’s social networks have added their worthwhile spins. This piece takes a light look, using Kuhn’s ideas with nudges from Feyerabend, Lakatos, and Latour, at the ongoing debate over dietary salt, a controversy that’s nuanced and long-lived. I’m not looking for “the truth” about salt, just watching science in real time.

Dietary Salt as a Kuhnian Case Study

The debate over salt’s role in blood pressure shows how science progresses, especially when viewed through the lens of Kuhn’s philosophy. It highlights the dynamics of shifting paradigms, consensus overreach, contrarian challenges, and the nonlinear, iterative path toward knowledge. This case reveals much about how science grapples with uncertainty, methodological complexity, and the interplay between evidence, belief, and rhetoric, even when relatively free from concerns about political and institutional influence.

In The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Kuhn proposed that science advances not steadily but through cycles of “normal science,” where a dominant paradigm shapes inquiry, and periods of crisis that can result in paradigm shifts. The salt–blood pressure debate, though not as dramatic in consequence as Einstein displacing Newton or as ideologically loaded as climate science, exemplifies these principles.

Normal Science and Consensus

Since the 1970s, medical authorities like the World Health Organization and the American Heart Association have endorsed the view that high sodium intake contributes to hypertension and thus increases cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk. This consensus stems from clinical trials such as the 2001 DASH-Sodium study, which demonstrated that reducing salt intake significantly (from 8 grams per day to 4) lowered blood pressure, especially among hypertensive individuals. This, in Kuhn’s view, is the dominant paradigm.

This framework – “less salt means better health” – has guided public health policies, including government dietary guidelines and initiatives like the UK’s salt reduction campaign. In Kuhnian terms, this is “normal science” at work. Researchers operate within an accepted model, refining it with meta-analyses and Randomized Control Trials, seeking data to reinforce it, and treating contradictory findings as anomalies or errors. Public health campaigns, like the AHA’s recommendation of less than 2.3 g/day of sodium, reflect this consensus. Governments’ involvement embodies institutional support.

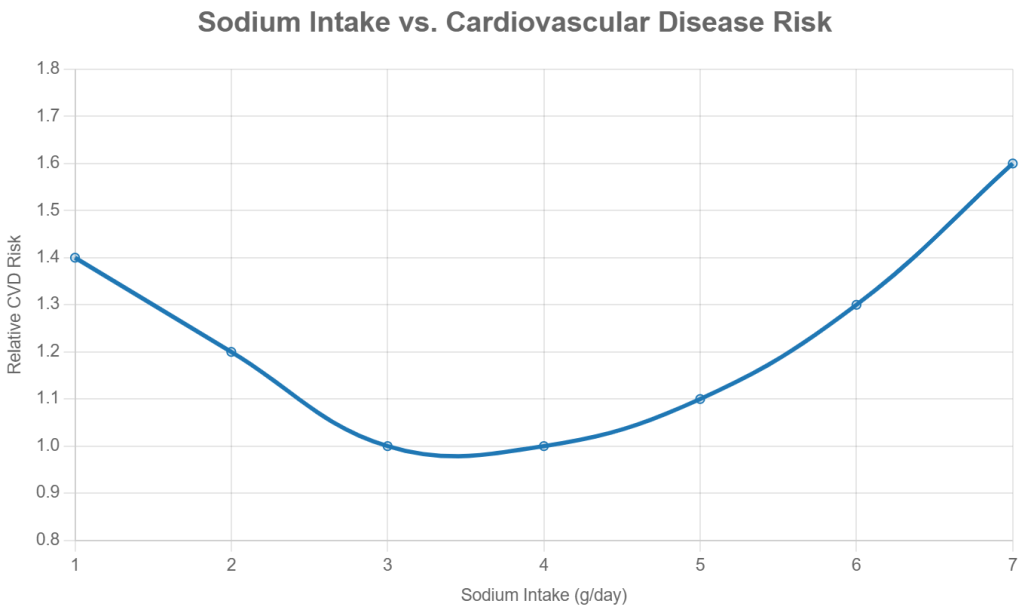

Anomalies and Contrarian Challenges

However, anomalies have emerged. For instance, a 2016 study by Mente et al. in The Lancet reported a U-shaped curve; both very low (less than 3 g/day) and very high (more than 5 g/day) sodium intakes appeared to be associated with increased CVD risk. This challenged the linear logic (“less salt, better health”) of the prevailing model. Although the differences in intake were not vast, the implications questioned whether current sodium guidelines were overly restrictive for people with normal blood pressure.

The video Salt & Blood Pressure: How Shady Science Sold America a Lie mirrors Galileo’s rhetorical flair, using provocative language such as “shady science” to challenge the establishment. Like Galileo’s defense of heliocentrism, contrarians in the salt debate (researchers like Mente) amplify anomalies to question dogma, sometimes exaggerating flaws in early studies (e.g., Lewis Dahl’s rat experiments) or alleging conspiracies (e.g., pharmaceutical influence). More in Feyerabend’s view than in Kuhn’s, this exaggeration and rhetoric might be desirable. It’s useful. It provides the challenges that the paradigm should be able to overcome to remain dominant.

These challenges haven’t led to a paradigm shift yet, as the consensus remains robust, supported by RCTs and global health data. But they highlight the Kuhnian tension between entrenched views and emerging evidence, pushing science to refine its understanding.

Framing the issue as a contrarian challenge might go something like this:

Evidence-based medicine sets treatment guidelines, but evidence-based medicine has not translated into evidence-based policy. Governments advise lowering salt intake, but that advice is supported by little robust evidence for the general population. Randomized controlled trials have not strongly supported the benefit of salt reduction for average people. Indeed, we see evidence that low salt might pose as great a risk.

Methodological Challenges

The question “Is salt bad for you?” is ill-posed. Evidence and reasoning say this question oversimplifies a complex issue: sodium’s effects vary by individual (e.g., salt sensitivity, genetics), diet (e.g., processed vs. whole foods), and context (e.g., baseline blood pressure, activity level). Science doesn’t deliver binary truths. Modern science gives probabilistic models, refined through iterative testing.

While randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have shown that reducing sodium intake can lower blood pressure, especially in sensitive groups, observational studies show that extremely low sodium is associated with poor health. This association may signal reverse causality, an error in reasoning. The data may simply reveal that sicker people eat less, not that they are harmed by low salt. This complexity reflects the limitations of study design and the challenges of isolating causal relationships in real-world populations. The above graph is a fairly typical dose-response curve for any nutrient.

The salt debate also underscores the inherent difficulty of studying diet and health. Total caloric intake, physical activity, genetic variation, and compliance all confound the relationship between sodium and health outcomes. Few studies look at salt intake as a fraction of body weight. If sodium recommendations were expressed as sodium density (mg/kcal), it might help accommodate individual energy needs and eating patterns more effectively.

Science as an Iterative Process

Despite flaws in early studies and the polemics of dissenters, the scientific communities continue to refine its understanding. For example, Japan’s national sodium reduction efforts since the 1970s have coincided with significant declines in stroke mortality, suggesting real-world benefits to moderation, even if the exact causal mechanisms remain complex.

Through a Kuhnian lens, we see a dominant paradigm shaped by institutional consensus and refined by accumulating evidence. But we also see the system’s limits: anomalies, confounding variables, and methodological disputes that resist easy resolution.

Contrarians, though sometimes rhetorically provocative or methodologically uneven, play a crucial role. Like the “puzzle-solvers” and “revolutionaries” in Kuhn’s model, they pressure the scientific establishment to reexamine assumptions and tighten methods. This isn’t a flaw in science; it’s the process at work.

Salt isn’t simply “good” or “bad.” The better scientific question is more conditional: How does salt affect different individuals, in which contexts, and through what mechanisms? Answering this requires humility, robust methodology, and the acceptance that progress usually comes in increments. Science moves forward not despite uncertainty, disputation and contradiction but because of them.

Content Strategy Beyond the Core Use Case

Posted by Bill Storage in Strategy on June 27, 2025

Introduction

In 2022, we wrote, as consultants to a startup, a proposal for an article exploring how graph computing could be applied to Bulk Metallic Glass (BMG), a class of advanced materials with an unusual atomic structure and high combinatorial complexity. The post tied a scientific domain to the strengths of the client’s graph computing platform – in this case, its ability to model deeply structured, non-obvious relationships that defy conventional flat-data systems.

This analysis is an invitation to reflect on the frameworks we use to shape our messaging – especially when we’re speaking to several audiences at once.