Posts Tagged physics

Removable Climbing Bolt Stress Under Offset Loading

Posted by Bill Storage in Engineering & Applied Physics on November 13, 2025

A Facebook Group has been discussing how load direction affects the stress state of removable bolts and their integral hangers. Hanger geometry causes axial loads to be applied with a small (~ 20mm) offset from the axis of the bolt. One topic of discussion is whether this offset creates a class-2 leverage effect, thereby increasing the stress in the bolt. Other aspects of the physics of these bolts warrant discussion. This can serve as a good starter, specifically addressing the leveraging/prying concern.

Intuition is a poor guide for this kind of problem. Nature doesn’t answer to consensus or gut feeling, and social reasoning won’t reveal how a bolt actually behaves. The only way to understand what’s happening is to go back to basic physics. That’s not a criticism of anyone’s judgment, it’s just the boundary the world imposes on us.

Examining the problem starts with simple physics (statics). Then you need to model how the system stretches and bends. You need to look at its stress state. So you need to calculate. A quick review of the relevant basics of mechanics might help. They are important to check the validity of the mental models we use to represent the real-world situation.

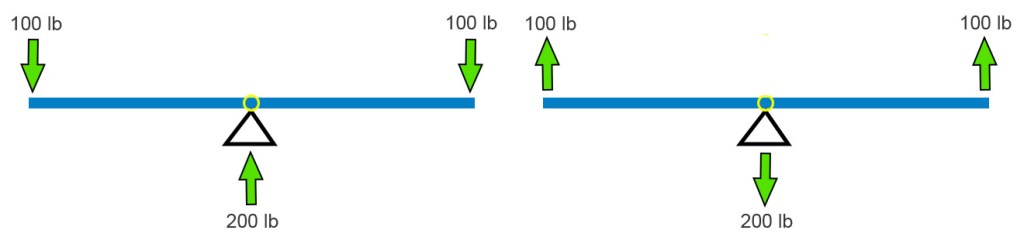

The classic balanced see-saw is at left below. The two 100 lb weights balance each other. The base pushes up on the beam with 200 pounds. We see Newton’s 1st Law in action. Sum of the down forces = sum of the up forces. If we say up forces are positive and down are negative, all the forces on the beam sum to zero. Simple. The see-saw works in tension too. Pull up with 2 ⋅ 100 pounds and the base pulls down by the same amount.

I’m going to stick will pull forces because they fit the bolt example better. A big kid and a little kid can still balance. Move the fulcrum toward the big kid (below left). The force the base pushes up with remains equal to the sum of the downward forces. This has to be in all cases. Newton (1st Law) must be satisfied.

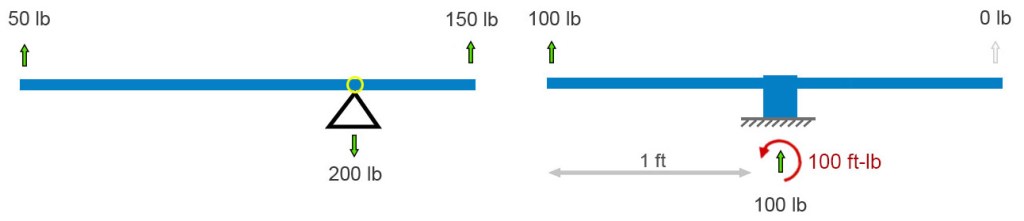

If the fulcrum – the pivot point – freezes up or is otherwise made immobile, the balancing act is no longer needed. The vertical forces still balance each other (cancel each other out), but now their is a twist on the base. Its left side wants to peel up. In addition to the sum of forces equaling zero, the sum of all twists must also sum to zero. A twist – I’ll use its physics name, moment – is defined as a force times the perpendicular distance through which it acts. In the above-right diagram, the 100 lb force is 1 foot from the base, so it applies a 100 ft-lb clockwise moment to the base (1 foot times 100 pounds = 100 ft-lb). (Notice we multiply the numbers and their units.) Therefore, to keep Isaac Newton happy, the ground must apply a 1 ft-lb counterclockwise moment (red curved arrow) to the base and beam that is fixed to it.

Anticipating a common point of confusion, I’ll point out here that, unlike the case where all the force arrows on this sort of “free body” diagram must sum to zero, there won’t necessarily be a visible curved arrow for every moment-balancing effect. Moment balance can exist between (1) a force times distance (100 lb up) and (2) a reaction moment (the counterclockwise moment applied by the ground), not between two drawn curved-arrows. If we focused on the ground and not the frozen see-saw, i.e., if we drew a free-body diagram of the ground and not the see-saw, we’d see a clockwise moment arrow representing the moment applied by the unbalanced base.

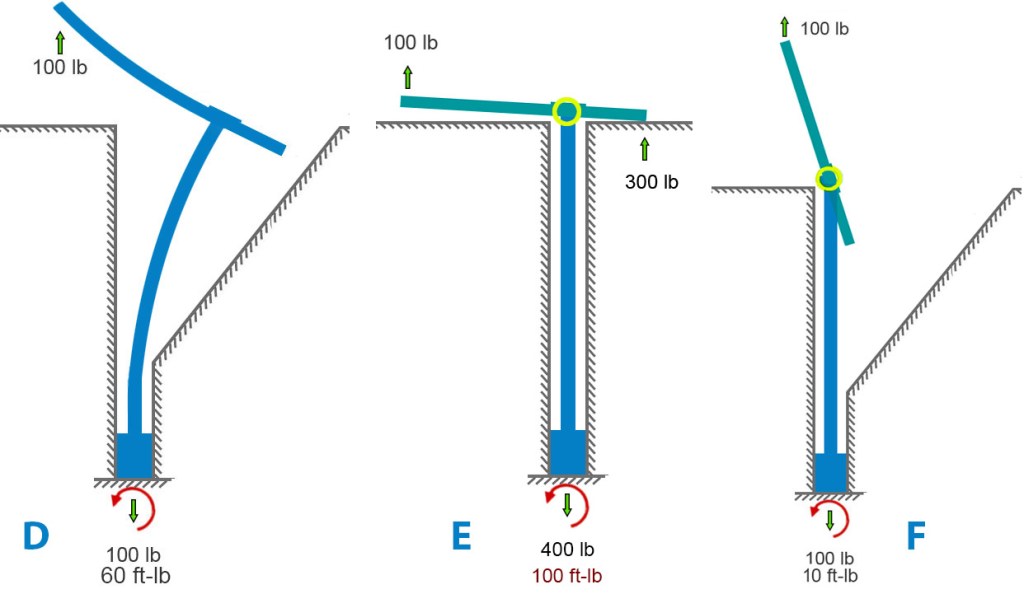

That’s all the pure statics we need to analyze these bolts. We’ll need mechanics of materials to analyze stresses. Let’s look at an idealized removable bolt in a hole. In particular, let’s look at an idealized Climbing Taiwan bolt. CT bolts have their integrated hangers welded to the bolt sleeve – fixed, like the base of the final see-saw above.

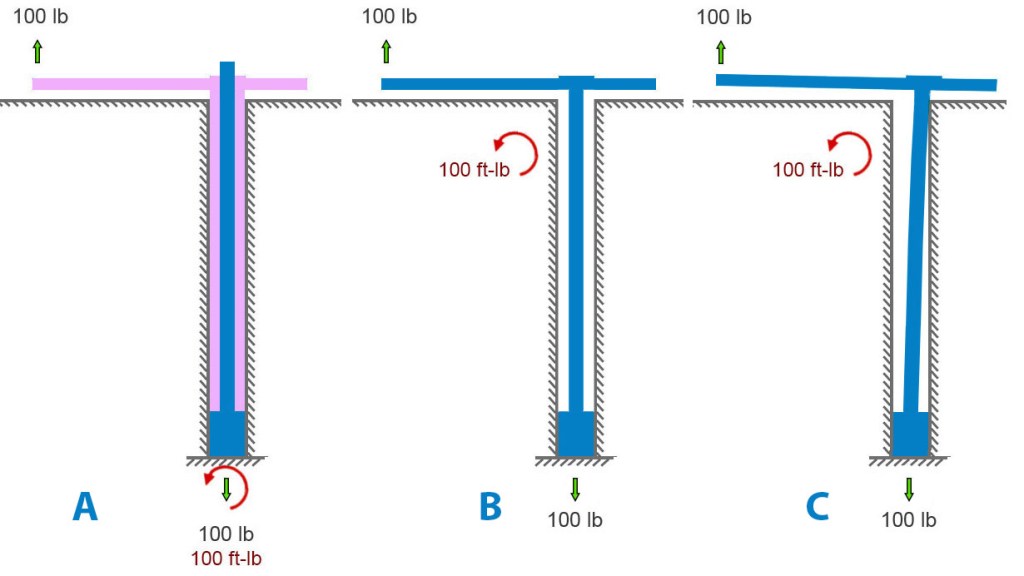

Figure A below shows an applied load of 100 pounds upward on the hanger. The bolt is anchored to rock at its base, at the bottom of the hole. A blue bolt is inside a pink hanger-sleeve assembly. The rock is pulling down on the base of the bolt with a force equal and opposite to the applied load. And the rock must apply a 100 ft-lb moment to the assembly to satisfy Newton. In figure A, it’s shown at the bottom of the hole.

But it need not be. Moments are global. Unlike forces, they aren’t applied at a point. We can move the curved arrow representing the moment – the twist the earth reacts to the load offset with – to any spot on the bolt assembly, as in the center diagram below. I further simplified the center diagram by removing the sleeve and modeling the situation as a single bolt-hanger assembly with space around it in the hole. For first-order calculations, given the small deflections involved, this simplification is acceptable. It helps us to see the key points.

We can allow the bolt to bend in the hole until it contacts the outside corner of the hole (figure B below). This changes very little besides adding some small counteracting horizontal forces there.

If we remove the rock and model a very bendy bolt, we get something like diagram D below. This leaves the forces unchanged but, in this extreme example, the moment is somewhat reduced because the moment arm (perpendicular distance between bolt and applied force) is considerably reduced by the bending.

We can also examine the case where the hanger is free to rotate on the bolt and sleeve (diagram E below). This is closer to the case of Petzl Pulse bolts. Here the 2nd-class lever mechanism comes into play. A “force-multiplier” is at work. If force-multiplier sounds like a bit of hand -waving, it is – forces aren’t multiplied per-se. We can do better and make Isaac Newton proud. A lever simply balances moments. If your hand is twice as far from the pivot as the load is, your hand needs only half the force because your longer distance gives your force more moment. Same moment, longer arm, smaller force. The 300-lb force at the hanger-rock (right side of bolt, figure E) contact exactly balances the 100-lb force that is three times farther away on the left side. Since both these forces pull upward on the hanger, the frictional force at the bottom of the whole becomes 400 pounds to balance it out. If no rock is on the right side of the hole, the hanger will rotate until it runs into something else (figure F).

Now we can look at stress, our bottom-line concern. Metal and rock and all other solids can take only so much stress, and then they break. For a material – say 304 steel – the stress at which it breaks is called its material strength. Material strength and stress are both measured in pounds per square inch (English) or Pascals (metric, often Megapascals, MPa). As a reference point, 304 steel breaks at a stress of 515 Mpa or 75,000 lb/sq-in. (75 ksi).

I will focus on figures A, B, C (identical for stress calcs), and E, since they are most like the real-world situations we’re concerned with. The various types of stresses all boil down to load divided by dimensions. Tensile stress is easy: axial load divided by cross sectional area. Since I’ve mixed English and metric units (for US reader familiarity), I’ll convert everything to metric units for stress calculation. Engineers use this symbol for stress: σ

Using σ = P/A to calculate axial stress, the numbers are:

- Axial load P= 100 lb =100 lbf = 444.82 N

- cross sectional area A = πd2/4 = 50.27 mm2

- radius c= 4 mm

Axial stress = σax = P/A = 8.85 MPa ≈ 1280 lb/sq-in.

The offset load imparts bending to the bolt. Calculating bending stress involves the concept of second moment of area (aka “cross-sectional moment of inertia” if you’re old-school). Many have tried to explain this concept simply. Fortunately, grasping its “why” is not essential to the point I want to make about axial vs. bending stress here. Nevertheless, here’s a short intro to the 2nd moment of area.

A beam under bending doesn’t care about how much material you have, it cares about how far that material is from the centerline. If you load a beam anchored at its ends in the middle, the top half (roughly) is in compression, the bottom half in tension. Top half squeezed, bottom stretched. Moment of area is a bookkeeping number that captures how much material you have times how far it sits from the centerline, squared. Add up every tiny patch of area, weighting each one by the square of its distance from the centerline. In shorthand, second moment of area (“I”) looks like this: I=∫y2dA

Now that you understand – or have taken on faith – the concept of second moment of area, we can calculate bending stress for the above scenario given the formula, σ = Mc/I.

Using σ = Mc/I, the numbers are:

- second moment I=πd4/64 = 201.06 mm4

- eccentric moment (i.e., the lever arm) = M = Pe=444.82 ⋅ 20 = 8896.44 N

Bending stress, σbend = Mc/I = 176.99 MPa ≈ 25,670 lb/sq-in.

The total stress of the bolt depends on which side of the bolt we are looking at. The maximum tensile stress is on the side that is getting stretched both by the applied axial load (100 lb) and by the fact that this load is offset. On that side of the bolt, we just add the axial and bending stress components (on the other side we would subtract the bending):

σtotal = σax ± σbend = 8.85 MPa + 176.99 MPa = 185.84 MPa ≈ 26,950 lb/sq-in.

Here we see something startling to folk who don’t do this kind of work. For situations like bolts and fasteners, the stress component due to the pullout force with no offset is insignificant compared to the effect of the offset. Bending completely dominates. By a factor of twenty in this case. Increasing the pure axial stress by increasing the applied axial load has little effect on the total stress in the bolt.

If we compare the A/B/C models with the E model, the pure-axial component grows by 18 MPa because of the higher reactive tensile force:

σtotal = σax ± σbend = 26.55 MPa + 176.99 MPa = 203.54 MPa ≈ 29521 lb/sq-in.

Adding the sleeve back to the model changes very little. It would reduce the force-multiplier effect in case E (thereby making it closer to A, B, and C) for several reasons that would take a lot of writing to explain well.

In the case of axially loaded removable bolts (not the use-case for which they were designed – significantly) the offset axial load greatly increases (completely dominates, in fact) the stress in the bolt. When a bolt carries an axial load that’s offset from its centerline, the problem isn’t any leverage created by the hanger’s prying geometry. That leverage effect is trivial. The offset itself produces a bending moment, and that bending drives the stress. For slender round members like bolts, bending overwhelms everything else.

Furthermore, published pull tests and my analysis of rock-limited vs. bolt-limited combinations of bolt diameter, length and rock strength suggest that bolt stress/strength is not a useful criterion for selecting removables. Based on what I’ve seen and experienced so far, I find the CT removables superior to other models for my concerns – durability, maintainability, reducing rock stress, and most importantly, ensuring that the wedge engages the back of the hole.

The End of Science Again

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science, Philosophy of Science on October 24, 2025

Dad says enough of this biblical exegesis and hermeneutics nonsense. He wants more science and history of science for iconoclasts and Kuhnians. I said that if prophetic exegesis was good enough for Isaac Newton – who spent most of his writing life on it – it’s good enough for me. But to keep the family together around the spectroscope, here’s another look at what’s gone terribly wrong with institutional science.

It’s been thirty years since John Horgan wrote The End of Science, arguing that fundamental discovery was nearing its end. He may have overstated the case, but his diagnosis of scientific fatigue struck a nerve. Horgan claimed that major insights – quantum mechanics, relativity, the big bang, evolution, the double helix – had already given us a comprehensive map of reality unlikely to change much. Science, he said, had become a victim of its own success, entering a phase of permanent normality, to borrow Thomas Kuhn’s term. Future research, in his view, would merely refine existing paradigms, pose unanswerable questions, or spin speculative theories with no empirical anchor.

Horgan still stands by that thesis. He notes the absence of paradigm-shifting revolutions and a decline in disruptive research. A 2023 Nature study analyzed forty-five million papers and nearly four million patents, finding a sharp drop in genuinely groundbreaking work since the mid-twentieth century. Research increasingly consolidates what’s known rather than breaking new ground. Horgan also raises the philosophical point that some puzzles may simply exceed our cognitive reach – a concern with deep historical roots. Consider consciousness, quantum interpretation, or other problems that might mark the brain’s limits. Perhaps AI will push those limits outward.

Students of History of Science will think of Auguste Comte’s famous claim that we’d never know the composition of the stars. He wasn’t stupid, just cautious. Epistemic humility. He knew collecting samples was impossible. What he couldn’t foresee was spectrometry, where the wavelengths of light a star emits reveal the quantum behavior of its electrons. Comte and his peers could never have imagined that; it was data that forced quantum mechanics upon us.

The same confidence of finality carried into the next generation of physics. In 1874, Philipp von Jolly reportedly advised young Max Planck not to pursue physics, since it was “virtually a finished subject,” with only small refinements left in measurement. That position was understandable: Maxwell’s equations unified electromagnetism, thermodynamics was triumphant, and the Newtonian worldview seemed complete. Only a few inconvenient anomalies remained.

Albert Michelson, in 1894, echoed the sentiment. “Most of the grand underlying principles have been firmly established,” he said. Physics had unified light, electricity, magnetism, and heat; the periodic table was filled in; the atom looked tidy. The remaining puzzles – Mercury’s orbit, blackbody radiation – seemed minor, the way dark matter does to some of us now. He was right in one sense: he had interpreted his world as coherently as possible with the evidence he had. Or had he?

Michelson’s remark came after his own 1887 experiment with Morley – the one that failed to detect Earth’s motion through the ether and, in hindsight, cracked the door to relativity. The irony is enormous. He had already performed the experiment that revealed something was deeply wrong, yet he didn’t see it that way. The null result struck him as a puzzle within the old paradigm, not a death blow to it. The idea that the speed of light might be constant for all observers, or that time and space themselves might bend, was too far outside the late-Victorian imagination. Lorentz, FitzGerald, and others kept right on patching the luminiferous ether.

Logicians will recognize the case for pessimistic meta-induction here: past prognosticators have always been wrong about the future, and inductive reasoning says they will be wrong again. Horgan may think his case is different, but I can’t see it. He was partially right, but overconfident about completeness – treating current theories as final, just as Comte, von Jolly, and Michelson once did.

Where Horgan was most right – territory he barely touched – is in seeing that institutions now ensure his prediction. Science stagnates not for lack of mystery but because its structures reward safety over risk. Peer review, grant culture, and the fetish for incrementalism make Kuhnian normal science permanent. Scientific American canned Horgan soon after The End of Science appeared. By the mid-90s, the magazine had already crossed the event horizon of integrity.

While researching his book, Horgan interviewed Edward Witten, already the central figure in the string-theory marketing machine. Witten rejected Kuhn’s model of revolutions, preferring a vision of seamless theoretical progress. No surprise. Horgan seemed wary of Witten’s confidence. He sensed that Witten’s serene belief in an ever-tightening net of theory was itself a symptom of closure.

From a Feyerabendian perspective, the irony is perfect. Paul Feyerabend would say that when a scientific culture begins to prize formal coherence, elegance, and mathematical completeness over empirical confrontation, it stops being revolutionary. In that sense, the Witten attitude itself initiates the decline of discovery.

String theory is the perfect case study: an extraordinary mathematical construct that’s absorbed immense intellectual capital without yielding a falsifiable prediction. To a cynic (or realist), it looks like a priesthood refining its liturgy. The Feyerabendian critique would be that modern science has been rationalized to death, more concerned with internal consistency and social prestige than with the rude encounter between theory and world. Witten’s world has continually expanded a body of coherent claims – they hold together, internally consistent. But science does not run on a coherence model of truth. It demands correspondence. (Coherence vs. correspondence models of truth was a big topic in analytic philosophy in the last century.) By correspondence theory of truth, we mean that theories must survive the test against nature. The creation of coherent ideas means nothing without it. Experience trumps theory, always – the scientific revolution in a nutshell.

Horgan didn’t say – though he should have – that Witten’s aesthetic of mathematical beauty has institutionalized epistemic stasis. The problem isn’t that science has run out of mysteries, as Horgan proposed, but that its practitioners have become too self-conscious, too invested in their architectures to risk tearing them down. Galileo rolls over.

Horgan sensed the paradox but never made it central. His End of Science was sociological and cognitive; a Feyerabendian would call it ideological. Science has become the very orthodoxy it once subverted.

Physics for Cold Cavers: NASA vs Hefty and Husky

Posted by Bill Storage in Engineering & Applied Physics on October 21, 2025

In the old days, every caver I knew carried a space blanket. Many still do. They come vacuum-packed in little squares that look like tea bricks, promising to help prevent hypothermia. They were originally marketed as NASA technology – because, in fact, they were. The original Mylar “space blanket” came out of the 1960s U.S. space program, meant to keep satellites and astronauts thermally stable in the vacuum of orbit. They reflected infrared radiation superbly, but only because they were surrounded by nothing. In a cave, you’re surrounded by something – cold, wet air – and that’s a very different problem.

A current ad says:

Reflects up to 90% of body heat to help prevent hypothermia and maintain core temperature during emergencies.

Another says:

Losing body heat in emergencies can quickly lead to hypothermia. Without understanding the science behind thermal protection, you might not use these tools effectively when they’re needed most.

This is your standard science-washing, techno-fetish, physics-theater advertising. Feynman called it cargo-cult science. But even Google Gemini told me:

For a vapor barrier in an emergency, a space blanket is better than a trash bag because it reflects radiant heat.

Premise true, conclusion false – non sequitur, an ancient Roman would say. It seems likely that advertising narratives played a quiet role in Google’s large-model-based AI system’s space-blanket blunder. That’s a topic for another time I guess.

Back to cold reality. At 50 degrees and 100 percent humidity, radiative heat loss is trivial. Radiative transfer at 10–15°C delta T is a rounding error compared to where your heat really goes. What matters is conduction to damp rock and convection to moving air, both of which a shiny sheet does little to stop. Worse, a rectangle of Mylar always leaks. Every fold and corner is a draft path, and soon you’re sitting in a crinkling echo chamber, shivering and reflecting nothing but a bad decision.

The contractor-size trash bag, meanwhile, is an unsung hero of survival. Poke a face hole near the bottom, pull it over your head, and you have a passable poncho that sheds drips instead of channeling them down your collar. You can sit on it, wrap your feet, and trap a pocket of warm, humid air that actually slows heat loss. Let a little moisture vent, and it works for an hour or two without turning clammy.

The space blanket survives mostly on myth – the glamour of NASA and the gleam of techno-hype. The homely trash bag simply works – better than anything near its size will. One was made for space, the other for the world we actually live in. Losing body heat in emergencies can quickly lead to hypothermia. Without getting the basics of thermal protection, you might not pick the best tool.

—

For those who need the physics, read on…

Heat leaves the body by three routes: conduction, convection, and radiation. Conduction is direct contact – warm skin meeting cool air, damp limestone, and mud. Convection is moving air stealing that warmed boundary layer and replacing it with fresh, cold air. Warm air is lighter. You warm the nearby air. It rises and sucks in fresh, cooler air. A circulating current arises.

At 50°F in a cave, conduction and convection dominate. The air is dense and wet, which means excellent thermal coupling. Each tiny current of air wicks warmth away far more effectively than dry air would. A trash bag stops that process cold. By trapping a thin layer of air and sealing it from drafts, it cuts off convective loss almost completely. It also slows conductive loss because still air, though not as good as down, is a decent insulator.

Radiation is infrared energy emitted from your skin and clothing into the surroundings. It follows the Stefan–Boltzmann law: power scales with the fourth power of absolute temperature. That sounds dramatic until you run the numbers. Between an 85°F body (skin temperature, roughly, 300° Kelvin) and a 50°F cave wall, the difference is about 27 Kelvin.

q = σ T4 A where q is heat transfer per unit time, T is temperature difference in Kelvins, and A is the radiative area.

Plug it in, and the radiative loss is about one percent of total heat loss – barely measurable compared to what you’re losing through air movement. The “90 percent reflection” claim is technically true in a vacuum, but in a cave or in Yosemite it’s a rounding error dressed up as science.

So the short version: the shiny Mylar sheet reflects an irrelevant component of heat loss while ignoring the main ones. The humble and opaque trash bag attacks the real physics of staying warm. It doesn’t sparkle, it gets the job done.

Extraordinary Popular Miscarriages of Science, Part 6 – String Theory

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science, Philosophy of Science on May 3, 2025

Introduction: A Historical Lens on String Theory

In 2006, I met John Heilbron, widely credited with turning the history of science from an emerging idea into a professional academic discipline. While James Conant and Thomas Kuhn laid the intellectual groundwork, it was Heilbron who helped build the institutions and frameworks that gave the field its shape. Through John I came to see that the history of science is not about names and dates – it’s about how scientific ideas develop, and why. It explores how science is both shaped by and shapes its cultural, social, and philosophical contexts. Science progresses not in isolation but as part of a larger human story.

The “discovery” of oxygen illustrates this beautifully. In the 18th century, Joseph Priestley, working within the phlogiston theory, isolated a gas he called “dephlogisticated air.” Antoine Lavoisier, using a different conceptual lens, reinterpreted it as a new element – oxygen – ushering in modern chemistry. This was not just a change in data, but in worldview.

When I met John, Lee Smolin’s The Trouble with Physics had just been published. Smolin, a physicist, critiques string theory not from outside science but from within its theoretical tensions. Smolin’s concerns echoed what I was learning from the history of science: that scientific revolutions often involve institutional inertia, conceptual blind spots, and sociopolitical entanglements.

My interest in string theory wasn’t about the physics. It became a test case for studying how scientific authority is built, challenged, and sustained. What follows is a distillation of 18 years of notes – string theory seen not from the lab bench, but from a historian’s desk.

A Brief History of String Theory

Despite its name, string theory is more accurately described as a theoretical framework – a collection of ideas that might one day lead to testable scientific theories. This alone is not a mark against it; many scientific developments begin as frameworks. Whether we call it a theory or a framework, it remains subject to a crucial question: does it offer useful models or testable predictions – or is it likely to in the foreseeable future?

String theory originated as an attempt to understand the strong nuclear force. In 1968, Gabriele Veneziano introduced a mathematical formula – the Veneziano amplitude – to describe the scattering of strongly interacting particles such as protons and neutrons. By 1970, Pierre Ramond incorporated supersymmetry into this approach, giving rise to superstrings that could account for both fermions and bosons. In 1974, Joël Scherk and John Schwarz discovered that the theory predicted a massless spin-2 particle with the properties of the hypothetical graviton. This led them to propose string theory not as a theory of the strong force, but as a potential theory of quantum gravity – a candidate “theory of everything.”

Around the same time, however, quantum chromodynamics (QCD) successfully explained the strong force via quarks and gluons, rendering the original goal of string theory obsolete. Interest in string theory waned, especially given its dependence on unobservable extra dimensions and lack of empirical confirmation.

That changed in 1984 when Michael Green and John Schwarz demonstrated that superstring theory could be anomaly-free in ten dimensions, reviving interest in its potential to unify all fundamental forces and particles. Researchers soon identified five mathematically consistent versions of superstring theory.

To reconcile ten-dimensional theory with the four-dimensional spacetime we observe, physicists proposed that the extra six dimensions are “compactified” into extremely small, curled-up spaces – typically represented as Calabi-Yau manifolds. This compactification allegedly explains why we don’t observe the extra dimensions.

In 1995, Edward Witten introduced M-theory, showing that the five superstring theories were different limits of a single 11-dimensional theory. By the early 2000s, researchers like Leonard Susskind and Shamit Kachru began exploring the so-called “string landscape” – a space of perhaps 10^500 (1 followed by 500 zeros) possible vacuum states, each corresponding to a different compactification scheme. This introduced serious concerns about underdetermination – the idea that available empirical evidence cannot determine which among many competing theories is correct.

Compactification introduces its own set of philosophical problems. Critics Lee Smolin and Peter Woit argue that compactification is not a prediction but a speculative rationalization: a move designed to save a theory rather than derive consequences from it. The enormous number of possible compactifications (each yielding different physics) makes string theory’s predictive power virtually nonexistent. The related challenge of moduli stabilization – specifying the size and shape of the compact dimensions – remains unresolved.

Despite these issues, string theory has influenced fields beyond high-energy physics. It has informed work in cosmology (e.g., inflation and the cosmic microwave background), condensed matter physics, and mathematics (notably algebraic geometry and topology). How deep and productive these connections run is difficult to assess without domain-specific expertise that I don’t have. String theory has, in any case, produced impressive mathematics. But mathematical fertility is not the same as scientific validity.

The Landscape Problem

Perhaps the most formidable challenge string theory faces is the landscape problem: the theory allows for an enormous number of solutions – on the order of 10^500. Each solution represents a possible universe, or “vacuum,” with its own physical constants and laws.

Why so many possibilities? The extra six dimensions required by string theory can be compactified in myriad ways. Each compactification, combined with possible energy configurations (called fluxes), gives rise to a distinct vacuum. This extreme flexibility means string theory can, in principle, accommodate nearly any observation. But this comes at the cost of predictive power.

Critics argue that if theorists can forever adjust the theory to match observations by choosing the right vacuum, the theory becomes unfalsifiable. On this view, string theory looks more like metaphysics than physics.

Some theorists respond by embracing the multiverse interpretation: all these vacua are real, and our universe is just one among many. The specific conditions we observe are then attributed to anthropic selection – we could only observe a universe that permits life like us. This view aligns with certain cosmological theories, such as eternal inflation, in which different regions of space settle into different vacua. But eternal inflation can exist independent of string theory, and none of this has been experimentally confirmed.

The Problem of Dominance

Since the 1980s, string theory has become a dominant force in theoretical physics. Major research groups at Harvard, Princeton, and Stanford focus heavily on it. Funding and institutional prestige have followed. Prominent figures like Brian Greene have elevated its public profile, helping transform it into both a scientific and cultural phenomenon.

This dominance raises concerns. Critics such as Smolin and Woit argue that string theory has crowded out alternative approaches like loop quantum gravity or causal dynamical triangulations. These alternatives receive less funding and institutional support, despite offering potentially fruitful lines of inquiry.

In The Trouble with Physics, Smolin describes a research culture in which dissent is subtly discouraged and young physicists feel pressure to align with the mainstream. He worries that this suppresses creativity and slows progress.

Estimates suggest that between 1,000 and 5,000 researchers work on string theory globally – a significant share of theoretical physics resources. Reliable numbers are hard to pin down.

Defenders of string theory argue that it has earned its prominence. They note that theoretical work is relatively inexpensive compared to experimental research, and that string theory remains the most developed candidate for unification. Still, the issue of how science sets its priorities – how it chooses what to fund, pursue, and elevate – remains contentious.

Wolfgang Lerche of CERN once called string theory “the Stanford propaganda machine working at its fullest.” As with climate science, 97% of string theorists agree that they don’t want to be defunded.

Thomas Kuhn’s Perspective

The logical positivists and Karl Popper would almost certainly dismiss string theory as unscientific due to its lack of empirical testability and falsifiability – core criteria in their respective philosophies of science. Thomas Kuhn would offer a more nuanced interpretation. He wouldn’t label string theory unscientific outright, but would express concern over its dominance and the marginalization of alternative approaches. In Kuhn’s framework, such conditions resemble the entrenchment of a paradigm during periods of normal science, potentially at the expense of innovation.

Some argue that string theory fits Kuhn’s model of a new paradigm, one that seeks to unify quantum mechanics and general relativity – two pillars of modern physics that remain fundamentally incompatible at high energies. Yet string theory has not brought about a Kuhnian revolution. It has not displaced existing paradigms, and its mathematical formalism is often incommensurable with traditional particle physics. From a Kuhnian perspective, the landscape problem may be seen as a growing accumulation of anomalies. But a paradigm shift requires a viable alternative – and none has yet emerged.

Lakatos and the Degenerating Research Program

Imre Lakatos offered a different lens, seeing science as a series of research programs characterized by a “hard core” of central assumptions and a “protective belt” of auxiliary hypotheses. A program is progressive if it predicts novel facts; it is degenerating if it resorts to ad hoc modifications to preserve the core.

For Lakatos, string theory’s hard core would be the idea that all particles are vibrating strings and that the theory unifies all fundamental forces. The protective belt would include compactification schemes, flux choices, and moduli stabilization – all adjusted to fit observations.

Critics like Sabine Hossenfelder argue that string theory is a degenerating research program: it absorbs anomalies without generating new, testable predictions. Others note that it is progressive in the Lakatosian sense because it has led to advances in mathematics and provided insights into quantum gravity. Historians of science are divided. Johansson and Matsubara (2011) argue that Lakatos would likely judge it degenerating; Cristin Chall (2019) offers a compelling counterpoint.

Perhaps string theory is progressive in mathematics but degenerating in physics.

The Feyerabend Bomb

Paul Feyerabend, who Lee Smolin knew from his time at Harvard, was the iconoclast of 20th-century philosophy of science. Feyerabend would likely have dismissed string theory as a dogmatic, aesthetic fantasy. He might write something like:

“String theory dazzles with equations and lulls physics into a trance. It’s a mathematical cathedral built in the sky, a triumph of elegance over experience. Science flourishes in rebellion. Fund the heretics.”

Even if this caricature overshoots, Feyerabend’s tools offer a powerful critique:

- Untestability: String theory’s predictions remain out of reach. Its core claims – extra dimensions, compactification, vibrational modes – cannot be tested with current or even foreseeable technology. Feyerabend challenged the privileging of untested theories (e.g., Copernicanism in its early days) over empirically grounded alternatives.

- Monopoly and suppression: String theory dominates intellectual and institutional space, crowding out alternatives. Eric Weinstein recently said, in Feyerabendian tones, “its dominance is unjustified and has resulted in a culture that has stifled critique, alternative views, and ultimately has damaged theoretical physics at a catastrophic level.”

- Methodological rigidity: Progress in string theory is often judged by mathematical consistency rather than by empirical verification – an approach reminiscent of scholasticism. Feyerabend would point to Johannes Kepler’s early attempt to explain planetary orbits using a purely geometric model based on the five Platonic solids. Kepler devoted 17 years to this elegant framework before abandoning it when observational data proved it wrong.

- Sociocultural dynamics: The dominance of string theory stems less from empirical success than from the influence and charisma of prominent advocates. Figures like Brian Greene, with their public appeal and institutional clout, help secure funding and shape the narrative – effectively sustaining the theory’s privileged position within the field.

- Epistemological overreach: The quest for a “theory of everything” may be misguided. Feyerabend would favor many smaller, diverse theories over a single grand narrative.

Historical Comparisons

Proponents say other landmark theories emerging from math predated their experimental confirmation. They compare string theory to historical cases. Examples include:

- Planet Neptune: Predicted by Urbain Le Verrier based on irregularities in Uranus’s orbit, observed in 1846.

- General Relativity: Einstein predicted the bending of light by gravity in 1915, confirmed by Arthur Eddington’s 1919 solar eclipse measurements.

- Higgs Boson: Predicted by the Standard Model in the 1960s, observed at the Large Hadron Collider in 2012.

- Black Holes: Predicted by general relativity, first direct evidence from gravitational waves observed in 2015.

- Cosmic Microwave Background: Predicted by the Big Bang theory (1922), discovered in 1965.

- Gravitational Waves: Predicted by general relativity, detected in 2015 by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO).

But these examples differ in kind. Their predictions were always testable in principle and ultimately tested. String theory, in contrast, operates at the Planck scale (~10^19 GeV), far beyond what current or foreseeable experiments can reach.

Special Concern Over Compactification

A concern I have not seen discussed elsewhere – even among critics like Smolin or Woit – is the epistemological status of compactification itself. Would the idea ever have arisen apart from the need to reconcile string theory’s ten dimensions with the four-dimensional spacetime we experience?

Compactification appears ad hoc, lacking grounding in physical intuition. It asserts that dimensions themselves can be small and curled – yet concepts like “small” and “curled” are defined within dimensions, not of them. Saying a dimension is small is like saying that time – not a moment in time, but time itself – can be “soon” or short in duration. It misapplies the very conceptual framework through which such properties are understood. At best, it’s a strained metaphor; at worst, it’s a category mistake and conceptual error.

This conceptual inversion reflects a logical gulf that proponents overlook or ignore. They say compactification is a mathematical consequence of the theory, not a contrivance. But without grounding in physical intuition – a deeper concern than empirical support – compactification remains a fix, not a forecast.

Conclusion

String theory may well contain a correct theory of fundamental physics. But without any plausible route to identifying it, string theory as practiced is bad science. It absorbs talent and resources, marginalizes dissent, and stifles alternative research programs. It is extraordinarily popular – and a miscarriage of science.

Let’s just fix the trolley

Posted by Bill Storage in Ethics, Philosophy on August 23, 2019

The classic formulation of the trolley-problem thought experiment goes something like this:

A runaway trolley hurtles toward five tied-up people on the main track. You see a lever that controls the switch. Pull it and the trolley switches to a side track, saving the five people, but will kill one person tied up on the side track. Your choices:

- Do nothing and let the trolley kill the five on the main track.

- Pull the lever, diverting the trolley onto the side track causing it to kill one person.

At this point the Ethics 101 class debates the issue and dives down the rabbit hole of deontology, virtue ethics, and consequentialism. That’s probably what Philippa Foot, who created the problem, expected. At this point engineers probably figure that the ethicists mean cable-cars (below right), not trolleys (streetcars, left), since the cable cars run on steep hills and rely on a single, crude mechanical brake while trolleys tend to stick to flatlands. But I digress.

At this point the Ethics 101 class debates the issue and dives down the rabbit hole of deontology, virtue ethics, and consequentialism. That’s probably what Philippa Foot, who created the problem, expected. At this point engineers probably figure that the ethicists mean cable-cars (below right), not trolleys (streetcars, left), since the cable cars run on steep hills and rely on a single, crude mechanical brake while trolleys tend to stick to flatlands. But I digress.

Many trolley problem variants exist. The first twist usually thrust upon trolley-problem rookies was called “the fat man variant” back in the mid 1970s when it first appeared. I’m not sure what it’s called now.

Many trolley problem variants exist. The first twist usually thrust upon trolley-problem rookies was called “the fat man variant” back in the mid 1970s when it first appeared. I’m not sure what it’s called now.

The same trolley and five people, but you’re on a bridge over the tracks, and you can block it with a very heavy object. You see a very fat man next to you. Your only timely option is to push him over the bridge and onto the track, which will certainly kill him and will certainly save the five. To push or not to push.

Ethicists debate the moral distinction between the two versions, focusing on intentionality, double-effect reasoning etc. Here I leave the trolley problems in the competent hands of said ethicists.

But psychologists and behavioral economists do not. They appropriate the trolley problems as an apparatus for contrasting emotion-based and reason-based cognitive subsystems. At other times it becomes all about the framing effect, one of the countless cognitive biases afflicting the subset of souls having no psych education. This bias is cited as the reason most people fail to see the two trolley problems as morally equivalent.

The degree of epistemological presumptuousness displayed by the behavioral economist here is mind-boggling. (Baby, you don’t know my mind…, as an old Doc Watson song goes.) Just because it’s a thought experiment doesn’t mean it’s immune to the rules of good design of experiments. The fat-man variant is radically different from the original trolley formulation. It is radically different in what the cognizing subject imagines upon hearing/reading the problem statement. The first scenario is at least plausible in the real world, the second isn’t remotely.

First off, pulling the lever is about as binary as it gets: it’s either in position A or position B and any middle choice is excluded outright. One can perhaps imagine a real-world switch sticking in the middle, causing an electrical short, but that possibility is remote from the minds of all but reliability engineers, who, without cracking open MIL-HDBK-217, know the likelihood of that failure mode to be around one per 10 million operations.

Pushing someone, a very heavy someone, over the railing of the bridge is a complex action, introducing all sorts of uncertainty. Of course the bridge has a railing; you’ve never seen one that didn’t. There’s a good chance the fat man’s center of gravity is lower than the top of the railing because it was designed to keep people from toppling over it. That means you can’t merely push him over; you more have to lift him up to the point where his CG is higher than the top of railing. But he’s heavy, not particularly passive, and stronger than you are. You can’t just push him into the railing expecting it to break either. Bridge railings are robust. Experience has told you this for your entire life. You know it even if you know nothing of civil engineering and pedestrian bridge safety codes. And if the term center of gravity (CG) is foreign to you, by age six you have grounded intuitions on the concept, along with moment of inertia and fulcrums.

Assume you believe you can somehow overcome the railing obstacle. Trolleys weigh about 100,000 pounds. The problem statement said the trolley is hurtling toward five people. That sounds like 10 miles per hour at minimum. Your intuitive sense of momentum (mass times velocity) and your intuitive sense of what it takes to decelerate the hurtling mass (Newton’s 2nd law, f = ma) simply don’t line up with the devious psychologist’s claim that the heavy person’s death will save five lives. The experimenter’s saying it – even in a thought experiment – doesn’t make it so, or even make it plausible. Your rational subsystem, whether thinking fast or slow, screams out that the chance of success with this plan is tiny. So you’re very likely to needlessly kill your bridge mate, and then watch five victims get squashed all by yourself.

The test subjects’ failure to see moral equivalence between the two trolley problems speaks to their rationality, not their cognitive bias. They know an absurd hypothetical when they see one. What looks like humanity’s logical ineptitude to so many behavioral economists appears to the engineers as humanity’s cultivated pragmatism and an intuitive grasp of physics, factor-relevance evaluation, and probability.

There’s book smart, and then there’s street smart, or trolley-tracks smart, as it were.

Recent Comments