Posts Tagged science

Removable Climbing Bolt Stress Under Offset Loading

Posted by Bill Storage in Engineering & Applied Physics on November 13, 2025

A Facebook Group has been discussing how load direction affects the stress state of removable bolts and their integral hangers. Hanger geometry causes axial loads to be applied with a small (~ 20mm) offset from the axis of the bolt. One topic of discussion is whether this offset creates a class-2 leverage effect, thereby increasing the stress in the bolt. Other aspects of the physics of these bolts warrant discussion. This can serve as a good starter, specifically addressing the leveraging/prying concern.

Intuition is a poor guide for this kind of problem. Nature doesn’t answer to consensus or gut feeling, and social reasoning won’t reveal how a bolt actually behaves. The only way to understand what’s happening is to go back to basic physics. That’s not a criticism of anyone’s judgment, it’s just the boundary the world imposes on us.

Examining the problem starts with simple physics (statics). Then you need to model how the system stretches and bends. You need to look at its stress state. So you need to calculate. A quick review of the relevant basics of mechanics might help. They are important to check the validity of the mental models we use to represent the real-world situation.

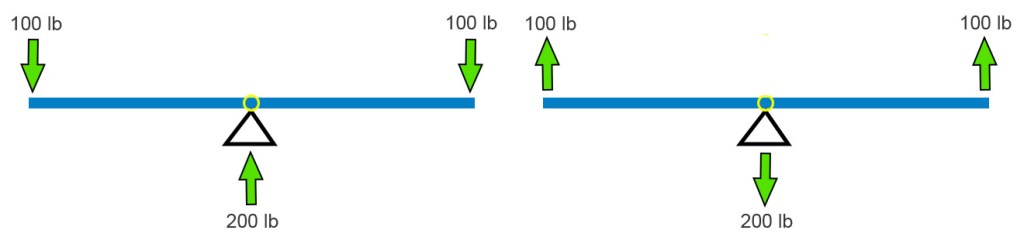

The classic balanced see-saw is at left below. The two 100 lb weights balance each other. The base pushes up on the beam with 200 pounds. We see Newton’s 1st Law in action. Sum of the down forces = sum of the up forces. If we say up forces are positive and down are negative, all the forces on the beam sum to zero. Simple. The see-saw works in tension too. Pull up with 2 ⋅ 100 pounds and the base pulls down by the same amount.

I’m going to stick will pull forces because they fit the bolt example better. A big kid and a little kid can still balance. Move the fulcrum toward the big kid (below left). The force the base pushes up with remains equal to the sum of the downward forces. This has to be in all cases. Newton (1st Law) must be satisfied.

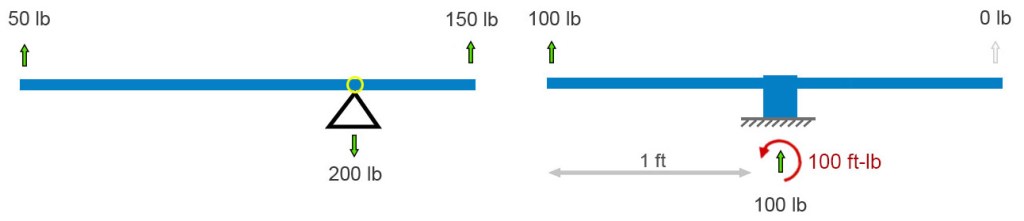

If the fulcrum – the pivot point – freezes up or is otherwise made immobile, the balancing act is no longer needed. The vertical forces still balance each other (cancel each other out), but now their is a twist on the base. Its left side wants to peel up. In addition to the sum of forces equaling zero, the sum of all twists must also sum to zero. A twist – I’ll use its physics name, moment – is defined as a force times the perpendicular distance through which it acts. In the above-right diagram, the 100 lb force is 1 foot from the base, so it applies a 100 ft-lb clockwise moment to the base (1 foot times 100 pounds = 100 ft-lb). (Notice we multiply the numbers and their units.) Therefore, to keep Isaac Newton happy, the ground must apply a 1 ft-lb counterclockwise moment (red curved arrow) to the base and beam that is fixed to it.

Anticipating a common point of confusion, I’ll point out here that, unlike the case where all the force arrows on this sort of “free body” diagram must sum to zero, there won’t necessarily be a visible curved arrow for every moment-balancing effect. Moment balance can exist between (1) a force times distance (100 lb up) and (2) a reaction moment (the counterclockwise moment applied by the ground), not between two drawn curved-arrows. If we focused on the ground and not the frozen see-saw, i.e., if we drew a free-body diagram of the ground and not the see-saw, we’d see a clockwise moment arrow representing the moment applied by the unbalanced base.

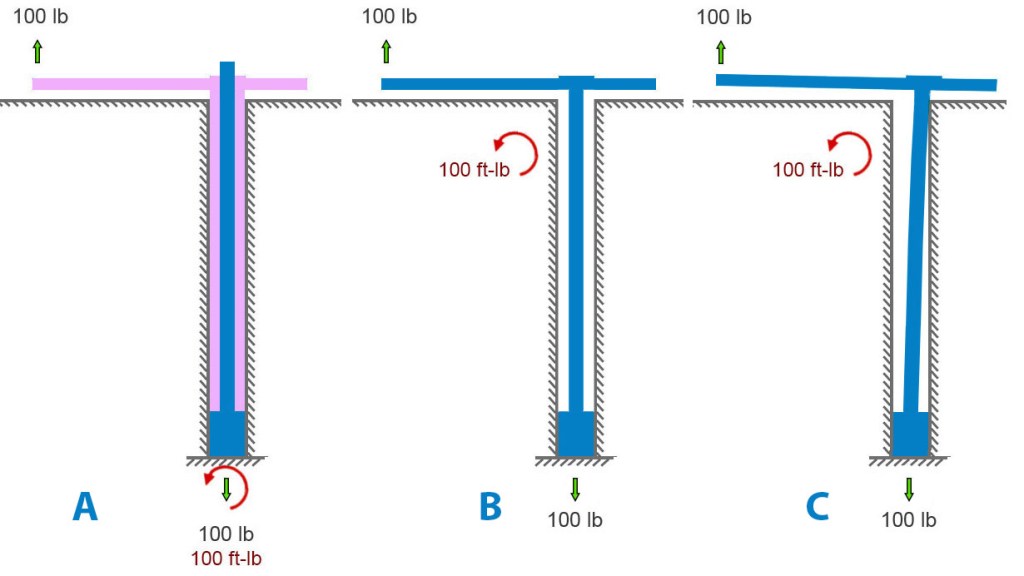

That’s all the pure statics we need to analyze these bolts. We’ll need mechanics of materials to analyze stresses. Let’s look at an idealized removable bolt in a hole. In particular, let’s look at an idealized Climbing Taiwan bolt. CT bolts have their integrated hangers welded to the bolt sleeve – fixed, like the base of the final see-saw above.

Figure A below shows an applied load of 100 pounds upward on the hanger. The bolt is anchored to rock at its base, at the bottom of the hole. A blue bolt is inside a pink hanger-sleeve assembly. The rock is pulling down on the base of the bolt with a force equal and opposite to the applied load. And the rock must apply a 100 ft-lb moment to the assembly to satisfy Newton. In figure A, it’s shown at the bottom of the hole.

But it need not be. Moments are global. Unlike forces, they aren’t applied at a point. We can move the curved arrow representing the moment – the twist the earth reacts to the load offset with – to any spot on the bolt assembly, as in the center diagram below. I further simplified the center diagram by removing the sleeve and modeling the situation as a single bolt-hanger assembly with space around it in the hole. For first-order calculations, given the small deflections involved, this simplification is acceptable. It helps us to see the key points.

We can allow the bolt to bend in the hole until it contacts the outside corner of the hole (figure B below). This changes very little besides adding some small counteracting horizontal forces there.

If we remove the rock and model a very bendy bolt, we get something like diagram D below. This leaves the forces unchanged but, in this extreme example, the moment is somewhat reduced because the moment arm (perpendicular distance between bolt and applied force) is considerably reduced by the bending.

We can also examine the case where the hanger is free to rotate on the bolt and sleeve (diagram E below). This is closer to the case of Petzl Pulse bolts. Here the 2nd-class lever mechanism comes into play. A “force-multiplier” is at work. If force-multiplier sounds like a bit of hand -waving, it is – forces aren’t multiplied per-se. We can do better and make Isaac Newton proud. A lever simply balances moments. If your hand is twice as far from the pivot as the load is, your hand needs only half the force because your longer distance gives your force more moment. Same moment, longer arm, smaller force. The 300-lb force at the hanger-rock (right side of bolt, figure E) contact exactly balances the 100-lb force that is three times farther away on the left side. Since both these forces pull upward on the hanger, the frictional force at the bottom of the whole becomes 400 pounds to balance it out. If no rock is on the right side of the hole, the hanger will rotate until it runs into something else (figure F).

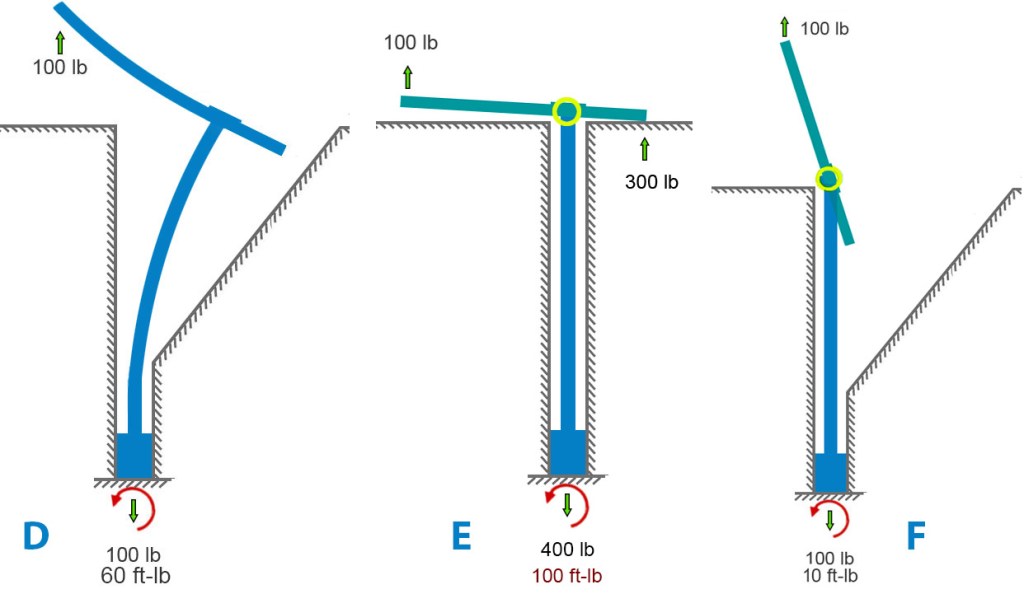

Now we can look at stress, our bottom-line concern. Metal and rock and all other solids can take only so much stress, and then they break. For a material – say 304 steel – the stress at which it breaks is called its material strength. Material strength and stress are both measured in pounds per square inch (English) or Pascals (metric, often Megapascals, MPa). As a reference point, 304 steel breaks at a stress of 515 Mpa or 75,000 lb/sq-in. (75 ksi).

I will focus on figures A, B, C (identical for stress calcs), and E, since they are most like the real-world situations we’re concerned with. The various types of stresses all boil down to load divided by dimensions. Tensile stress is easy: axial load divided by cross sectional area. Since I’ve mixed English and metric units (for US reader familiarity), I’ll convert everything to metric units for stress calculation. Engineers use this symbol for stress: σ

Using σ = P/A to calculate axial stress, the numbers are:

- Axial load P= 100 lb =100 lbf = 444.82 N

- cross sectional area A = πd2/4 = 50.27 mm2

- radius c= 4 mm

Axial stress = σax = P/A = 8.85 MPa ≈ 1280 lb/sq-in.

The offset load imparts bending to the bolt. Calculating bending stress involves the concept of second moment of area (aka “cross-sectional moment of inertia” if you’re old-school). Many have tried to explain this concept simply. Fortunately, grasping its “why” is not essential to the point I want to make about axial vs. bending stress here. Nevertheless, here’s a short intro to the 2nd moment of area.

A beam under bending doesn’t care about how much material you have, it cares about how far that material is from the centerline. If you load a beam anchored at its ends in the middle, the top half (roughly) is in compression, the bottom half in tension. Top half squeezed, bottom stretched. Moment of area is a bookkeeping number that captures how much material you have times how far it sits from the centerline, squared. Add up every tiny patch of area, weighting each one by the square of its distance from the centerline. In shorthand, second moment of area (“I”) looks like this: I=∫y2dA

Now that you understand – or have taken on faith – the concept of second moment of area, we can calculate bending stress for the above scenario given the formula, σ = Mc/I.

Using σ = Mc/I, the numbers are:

- second moment I=πd4/64 = 201.06 mm4

- eccentric moment (i.e., the lever arm) = M = Pe=444.82 ⋅ 20 = 8896.44 N

Bending stress, σbend = Mc/I = 176.99 MPa ≈ 25,670 lb/sq-in.

The total stress of the bolt depends on which side of the bolt we are looking at. The maximum tensile stress is on the side that is getting stretched both by the applied axial load (100 lb) and by the fact that this load is offset. On that side of the bolt, we just add the axial and bending stress components (on the other side we would subtract the bending):

σtotal = σax ± σbend = 8.85 MPa + 176.99 MPa = 185.84 MPa ≈ 26,950 lb/sq-in.

Here we see something startling to folk who don’t do this kind of work. For situations like bolts and fasteners, the stress component due to the pullout force with no offset is insignificant compared to the effect of the offset. Bending completely dominates. By a factor of twenty in this case. Increasing the pure axial stress by increasing the applied axial load has little effect on the total stress in the bolt.

If we compare the A/B/C models with the E model, the pure-axial component grows by 18 MPa because of the higher reactive tensile force:

σtotal = σax ± σbend = 26.55 MPa + 176.99 MPa = 203.54 MPa ≈ 29521 lb/sq-in.

Adding the sleeve back to the model changes very little. It would reduce the force-multiplier effect in case E (thereby making it closer to A, B, and C) for several reasons that would take a lot of writing to explain well.

In the case of axially loaded removable bolts (not the use-case for which they were designed – significantly) the offset axial load greatly increases (completely dominates, in fact) the stress in the bolt. When a bolt carries an axial load that’s offset from its centerline, the problem isn’t any leverage created by the hanger’s prying geometry. That leverage effect is trivial. The offset itself produces a bending moment, and that bending drives the stress. For slender round members like bolts, bending overwhelms everything else.

Furthermore, published pull tests and my analysis of rock-limited vs. bolt-limited combinations of bolt diameter, length and rock strength suggest that bolt stress/strength is not a useful criterion for selecting removables. Based on what I’ve seen and experienced so far, I find the CT removables superior to other models for my concerns – durability, maintainability, reducing rock stress, and most importantly, ensuring that the wedge engages the back of the hole.

The End of Science Again

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science, Philosophy of Science on October 24, 2025

Dad says enough of this biblical exegesis and hermeneutics nonsense. He wants more science and history of science for iconoclasts and Kuhnians. I said that if prophetic exegesis was good enough for Isaac Newton – who spent most of his writing life on it – it’s good enough for me. But to keep the family together around the spectroscope, here’s another look at what’s gone terribly wrong with institutional science.

It’s been thirty years since John Horgan wrote The End of Science, arguing that fundamental discovery was nearing its end. He may have overstated the case, but his diagnosis of scientific fatigue struck a nerve. Horgan claimed that major insights – quantum mechanics, relativity, the big bang, evolution, the double helix – had already given us a comprehensive map of reality unlikely to change much. Science, he said, had become a victim of its own success, entering a phase of permanent normality, to borrow Thomas Kuhn’s term. Future research, in his view, would merely refine existing paradigms, pose unanswerable questions, or spin speculative theories with no empirical anchor.

Horgan still stands by that thesis. He notes the absence of paradigm-shifting revolutions and a decline in disruptive research. A 2023 Nature study analyzed forty-five million papers and nearly four million patents, finding a sharp drop in genuinely groundbreaking work since the mid-twentieth century. Research increasingly consolidates what’s known rather than breaking new ground. Horgan also raises the philosophical point that some puzzles may simply exceed our cognitive reach – a concern with deep historical roots. Consider consciousness, quantum interpretation, or other problems that might mark the brain’s limits. Perhaps AI will push those limits outward.

Students of History of Science will think of Auguste Comte’s famous claim that we’d never know the composition of the stars. He wasn’t stupid, just cautious. Epistemic humility. He knew collecting samples was impossible. What he couldn’t foresee was spectrometry, where the wavelengths of light a star emits reveal the quantum behavior of its electrons. Comte and his peers could never have imagined that; it was data that forced quantum mechanics upon us.

The same confidence of finality carried into the next generation of physics. In 1874, Philipp von Jolly reportedly advised young Max Planck not to pursue physics, since it was “virtually a finished subject,” with only small refinements left in measurement. That position was understandable: Maxwell’s equations unified electromagnetism, thermodynamics was triumphant, and the Newtonian worldview seemed complete. Only a few inconvenient anomalies remained.

Albert Michelson, in 1894, echoed the sentiment. “Most of the grand underlying principles have been firmly established,” he said. Physics had unified light, electricity, magnetism, and heat; the periodic table was filled in; the atom looked tidy. The remaining puzzles – Mercury’s orbit, blackbody radiation – seemed minor, the way dark matter does to some of us now. He was right in one sense: he had interpreted his world as coherently as possible with the evidence he had. Or had he?

Michelson’s remark came after his own 1887 experiment with Morley – the one that failed to detect Earth’s motion through the ether and, in hindsight, cracked the door to relativity. The irony is enormous. He had already performed the experiment that revealed something was deeply wrong, yet he didn’t see it that way. The null result struck him as a puzzle within the old paradigm, not a death blow to it. The idea that the speed of light might be constant for all observers, or that time and space themselves might bend, was too far outside the late-Victorian imagination. Lorentz, FitzGerald, and others kept right on patching the luminiferous ether.

Logicians will recognize the case for pessimistic meta-induction here: past prognosticators have always been wrong about the future, and inductive reasoning says they will be wrong again. Horgan may think his case is different, but I can’t see it. He was partially right, but overconfident about completeness – treating current theories as final, just as Comte, von Jolly, and Michelson once did.

Where Horgan was most right – territory he barely touched – is in seeing that institutions now ensure his prediction. Science stagnates not for lack of mystery but because its structures reward safety over risk. Peer review, grant culture, and the fetish for incrementalism make Kuhnian normal science permanent. Scientific American canned Horgan soon after The End of Science appeared. By the mid-90s, the magazine had already crossed the event horizon of integrity.

While researching his book, Horgan interviewed Edward Witten, already the central figure in the string-theory marketing machine. Witten rejected Kuhn’s model of revolutions, preferring a vision of seamless theoretical progress. No surprise. Horgan seemed wary of Witten’s confidence. He sensed that Witten’s serene belief in an ever-tightening net of theory was itself a symptom of closure.

From a Feyerabendian perspective, the irony is perfect. Paul Feyerabend would say that when a scientific culture begins to prize formal coherence, elegance, and mathematical completeness over empirical confrontation, it stops being revolutionary. In that sense, the Witten attitude itself initiates the decline of discovery.

String theory is the perfect case study: an extraordinary mathematical construct that’s absorbed immense intellectual capital without yielding a falsifiable prediction. To a cynic (or realist), it looks like a priesthood refining its liturgy. The Feyerabendian critique would be that modern science has been rationalized to death, more concerned with internal consistency and social prestige than with the rude encounter between theory and world. Witten’s world has continually expanded a body of coherent claims – they hold together, internally consistent. But science does not run on a coherence model of truth. It demands correspondence. (Coherence vs. correspondence models of truth was a big topic in analytic philosophy in the last century.) By correspondence theory of truth, we mean that theories must survive the test against nature. The creation of coherent ideas means nothing without it. Experience trumps theory, always – the scientific revolution in a nutshell.

Horgan didn’t say – though he should have – that Witten’s aesthetic of mathematical beauty has institutionalized epistemic stasis. The problem isn’t that science has run out of mysteries, as Horgan proposed, but that its practitioners have become too self-conscious, too invested in their architectures to risk tearing them down. Galileo rolls over.

Horgan sensed the paradox but never made it central. His End of Science was sociological and cognitive; a Feyerabendian would call it ideological. Science has become the very orthodoxy it once subverted.

From Aqueducts to Algorithms: The Cost of Consensus

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science on July 9, 2025

The Scientific Revolution, we’re taught, began in the 17th century – a European eruption of testable theories, mathematical modeling, and empirical inquiry from Copernicus to Newton. Newton was the first scientist, or rather, the last magician, many historians say. That period undeniably transformed our understanding of nature.

Historians increasingly question whether a discrete “scientific revolution” ever happened. Floris Cohen called the label a straightjacket. It’s too simplistic to explain why modern science, defined as the pursuit of predictive, testable knowledge by way of theory and observation, emerged when and where it did. The search for “why then?” leads to Protestantism, capitalism, printing, discovered Greek texts, scholasticism, even weather. That’s mostly just post hoc theorizing.

Still, science clearly gained unprecedented momentum in early modern Europe. Why there? Why then? Good questions, but what I wonder, is why not earlier – even much earlier.

Europe had intellectual fireworks throughout the medieval period. In 1320, Jean Buridan nearly articulated inertia. His anticipation of Newton is uncanny, three centuries earlier:

“When a mover sets a body in motion he implants into it a certain impetus, that is, a certain force enabling a body to move in the direction in which the mover starts it, be it upwards, downwards, sidewards, or in a circle. The implanted impetus increases in the same ratio as the velocity. It is because of this impetus that a stone moves on after the thrower has ceased moving it. But because of the resistance of the air (and also because of the gravity of the stone) … the impetus will weaken all the time. Therefore the motion of the stone will be gradually slower, and finally the impetus is so diminished or destroyed that the gravity of the stone prevails and moves the stone towards its natural place.”

Robert Grosseteste, in 1220, proposed the experiment-theory iteration loop. In his commentary on Aristotle’s Posterior Analytics, he describes what he calls “resolution and composition”, a method of reasoning that moves from particulars to universals, then from universals back to particulars to make predictions. Crucially, he emphasizes that both phases require experimental verification.

In 1360, Nicole Oresme gave explicit medieval support for a rotating Earth:

“One cannot by any experience whatsoever demonstrate that the heavens … are moved with a diurnal motion… One can not see that truly it is the sky that is moving, since all movement is relative.”

He went on to say that the air moves with the Earth, so no wind results. He challenged astrologers:

“The heavens do not act on the intellect or will… which are superior to corporeal things and not subject to them.”

Even if one granted some influence of the stars on matter, Oresme wrote, their effects would be drowned out by terrestrial causes.

These were dead ends, it seems. Some blame the Black Death, but the plague left surprisingly few marks in the intellectual record. Despite mass mortality, history shows politics, war, and religion marching on. What waned was interest in reviving ancient learning. The cultural machinery required to keep the momentum going stalled. Critical, collaborative, self-correcting inquiry didn’t catch on.

A similar “almost” occurred in the Islamic world between the 10th and 16th centuries. Ali al-Qushji and al-Birjandi developed sophisticated models of planetary motion and even toyed with Earth’s rotation. A layperson would struggle to distinguish some of al-Birjandi’s thought experiments from Galileo’s. But despite a wealth of brilliant scholars, there were few institutions equipped or allowed to convert knowledge into power. The idea that observation could disprove theory or override inherited wisdom was socially and theologically unacceptable. That brings us to a less obvious candidate – ancient Rome.

Rome is famous for infrastructure – aqueducts, cranes, roads, concrete, and central heating – but not scientific theory. The usual story is that Roman thought was too practical, too hierarchical, uninterested in pure understanding.

One text complicates that story: De Architectura, a ten-volume treatise by Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, written during the reign of Augustus. Often described as a manual for builders, De Architectura is far more than a how-to. It is a theoretical framework for knowledge, part engineering handbook, part philosophy of science.

Vitruvius was no scientist, but his ideas come astonishingly close to the scientific method. He describes devices like the Archimedean screw or the aeolipile, a primitive steam engine. He discusses acoustics in theater design, and a cosmological models passed down from the Greeks. He seems to describe vanishing point perspective, something seen in some Roman art of his day. Most importantly, he insists on a synthesis of theory, mathematics, and practice as the foundation of engineering. His describes something remarkably similar to what we now call science:

“The engineer should be equipped with knowledge of many branches of study and varied kinds of learning… This knowledge is the child of practice and theory. Practice is the continuous and regular exercise of employment… according to the design of a drawing. Theory, on the other hand, is the ability to demonstrate and explain the productions of dexterity on the principles of proportion…”

“Engineers who have aimed at acquiring manual skill without scholarship have never been able to reach a position of authority… while those who relied only upon theories and scholarship were obviously hunting the shadow, not the substance. But those who have a thorough knowledge of both… have the sooner attained their object and carried authority with them.”

This is more than just a plea for well-rounded education. H e gives a blueprint for a systematic, testable, collaborative knowledge-making enterprise. If Vitruvius and his peers glimpsed the scientific method, why didn’t Rome take the next step?

The intellectual capacity was clearly there. And Roman engineers, like their later European successors, had real technological success. The problem, it seems, was societal receptiveness.

Science, as Thomas Kuhn famously brough to our attention, is a social institution. It requires the belief that man-made knowledge can displace received wisdom. It depends on openness to revision, structured dissent, and collaborative verification. These were values that the Roman elite culture distrusted.

When Vitruvius was writing, Rome had just emerged from a century of brutal civil war. The Senate and Augustus were engaged in consolidating power, not questioning assumptions. Innovation, especially social innovation, was feared. In a political culture that prized stability, hierarchy, and tradition, the idea that empirical discovery could drive change likely felt dangerous.

We see this in Cicero’s conservative rhetoric, in Seneca’s moralism, and in the correspondence between Pliny and Trajan, where even mild experimentation could be viewed as subversive. The Romans could build aqueducts, but they wouldn’t fund a lab.

Like the Islamic world centuries later, Rome had scholars but not systems. Knowledge existed, but the scaffolding to turn it into science – collective inquiry, reproducibility, peer review, invitations for skeptics to refute – never emerged.

Vitruvius’s De Architectura deserves more attention, not just as a technical manual but as a proto-scientific document. It suggests that the core ideas behind science were not exclusive to early modern Europe. They’ve flickered into existence before, in Alexandria, Baghdad, Paris, and Rome, only to be extinguished by lack of institutional fit.

That science finally took root in the 17th century had less to do with discovery than with a shift in what society was willing to do with discovery. The real revolution wasn’t in Newton’s laboratory, it was in the culture.

Rome’s Modern Echo?

It’s worth asking whether we’re becoming more Roman ourselves. Today, we have massively resourced research institutions, global scientific networks, and generations of accumulated knowledge. Yet, in some domains, science feels oddly stagnant or brittle. Dissenting views are not always engaged but dismissed, not for lack of evidence, but for failing to fit a prevailing narrative.

We face a serious, maybe existential question. Does increasing ideological conformity, especially in academia, foster or hamper science?

Obviously, some level of consensus is essential. Without shared standards, peer review collapses. Climate models, particle accelerators, and epidemiological studies rely on a staggering degree of cooperation and shared assumptions. Consensus can be a hard-won product of good science. And it can run perilously close to dogma. In the past twenty years we’ve seen consensus increasingly enforced by legal action, funding monopolies, and institutional ostracism.

String theory may (or may not) be physics’ great white whale. It’s mathematically exquisite but empirically elusive. For decades, critics like Lee Smolin and Peter Woit have argued that string theory has enjoyed a monopoly on prestige and funding while producing little testable output. Dissenters are often marginalized.

Climate science is solidly evidence-based, but responsible scientists point to constant revision of old evidence. Critics like Judith Curry or Roger Pielke Jr. have raised methodological or interpretive concerns, only to find themselves publicly attacked or professionally sidelined. Their critique is labeled denial. Scientific American called Curry a heretic. Lawsuits, like Michael Mann’s long battle with critics, further signal a shift from scientific to pre-scientific modes of settling disagreement.

Jonathan Haidt, Lee Jussim, and others have documented the sharp political skew of academia, particularly in the humanities and social sciences, but increasingly in hard sciences too. When certain political assumptions are so embedded, they become invisible. Dissent is called heresy in an academic monoculture. This constrains the range of questions scientists are willing to ask, a problem that affects both research and teaching. If the only people allowed to judge your work must first agree with your premises, then peer review becomes a mechanism of consensus enforcement, not knowledge validation.

When Paul Feyerabend argued that “the separation of science and state” might be as important as the separation of church and state, he was pushing back against conservative technocratic arrogance. Ironically, his call for epistemic anarchism now resonates more with critics on the right than the left. Feyerabend warned that uniformity in science, enforced by centralized control, stifles creativity and detaches science from democratic oversight.

Today, science and the state, including state-adjacent institutions like universities, are deeply entangled. Funding decisions, hiring, and even allowable questions are influenced by ideology. This alignment with prevailing norms creates a kind of soft theocracy of expert opinion.

The process by which scientific knowledge is validated must be protected from both politicization and monopolization, whether that comes from the state, the market, or a cultural elite.

Science is only self-correcting if its institutions are structured to allow correction. That means tolerating dissent, funding competing views, and resisting the urge to litigate rather than debate. If Vitruvius teaches us anything, it’s that knowing how science works is not enough. Rome had theory, math, and experimentation. What it lacked was a social system that could tolerate what those tools would eventually uncover. We do not yet lack that system, but we are testing the limits.

Grains of Truth: Science and Dietary Salt

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science, Philosophy of Science on June 29, 2025

Science doesn’t proceeds in straight lines. It meanders, collides, and battles over its big ideas. Thomas Kuhn’s view of science as cycles of settled consensus punctuated by disruptive challenges is a great way to understand this messiness, though later approaches, like Imre Lakatos’s structured research programs, Paul Feyerabend’s radical skepticism, and Bruno Latour’s focus on science’s social networks have added their worthwhile spins. This piece takes a light look, using Kuhn’s ideas with nudges from Feyerabend, Lakatos, and Latour, at the ongoing debate over dietary salt, a controversy that’s nuanced and long-lived. I’m not looking for “the truth” about salt, just watching science in real time.

Dietary Salt as a Kuhnian Case Study

The debate over salt’s role in blood pressure shows how science progresses, especially when viewed through the lens of Kuhn’s philosophy. It highlights the dynamics of shifting paradigms, consensus overreach, contrarian challenges, and the nonlinear, iterative path toward knowledge. This case reveals much about how science grapples with uncertainty, methodological complexity, and the interplay between evidence, belief, and rhetoric, even when relatively free from concerns about political and institutional influence.

In The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Kuhn proposed that science advances not steadily but through cycles of “normal science,” where a dominant paradigm shapes inquiry, and periods of crisis that can result in paradigm shifts. The salt–blood pressure debate, though not as dramatic in consequence as Einstein displacing Newton or as ideologically loaded as climate science, exemplifies these principles.

Normal Science and Consensus

Since the 1970s, medical authorities like the World Health Organization and the American Heart Association have endorsed the view that high sodium intake contributes to hypertension and thus increases cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk. This consensus stems from clinical trials such as the 2001 DASH-Sodium study, which demonstrated that reducing salt intake significantly (from 8 grams per day to 4) lowered blood pressure, especially among hypertensive individuals. This, in Kuhn’s view, is the dominant paradigm.

This framework – “less salt means better health” – has guided public health policies, including government dietary guidelines and initiatives like the UK’s salt reduction campaign. In Kuhnian terms, this is “normal science” at work. Researchers operate within an accepted model, refining it with meta-analyses and Randomized Control Trials, seeking data to reinforce it, and treating contradictory findings as anomalies or errors. Public health campaigns, like the AHA’s recommendation of less than 2.3 g/day of sodium, reflect this consensus. Governments’ involvement embodies institutional support.

Anomalies and Contrarian Challenges

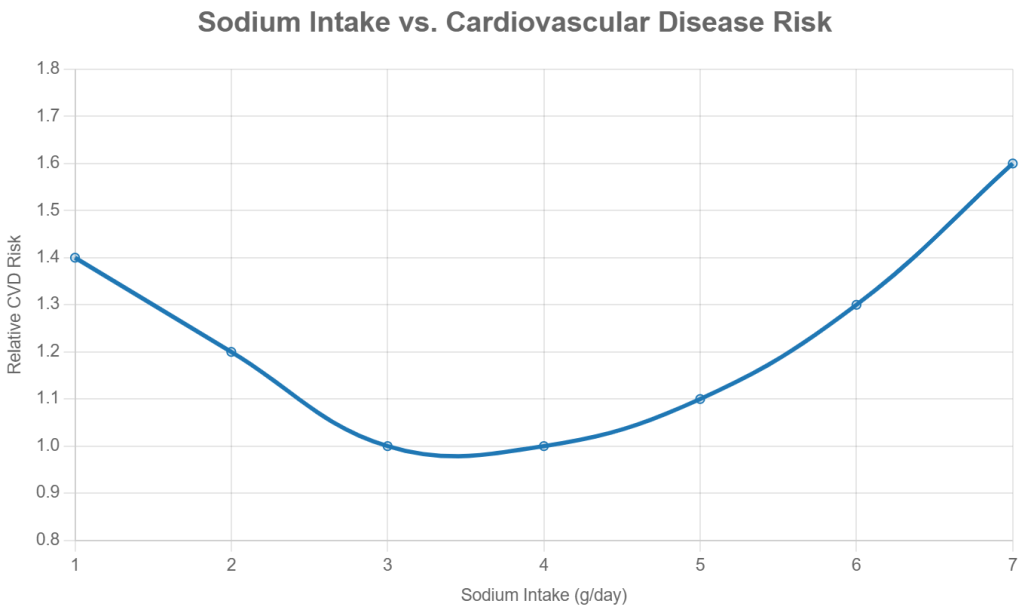

However, anomalies have emerged. For instance, a 2016 study by Mente et al. in The Lancet reported a U-shaped curve; both very low (less than 3 g/day) and very high (more than 5 g/day) sodium intakes appeared to be associated with increased CVD risk. This challenged the linear logic (“less salt, better health”) of the prevailing model. Although the differences in intake were not vast, the implications questioned whether current sodium guidelines were overly restrictive for people with normal blood pressure.

The video Salt & Blood Pressure: How Shady Science Sold America a Lie mirrors Galileo’s rhetorical flair, using provocative language such as “shady science” to challenge the establishment. Like Galileo’s defense of heliocentrism, contrarians in the salt debate (researchers like Mente) amplify anomalies to question dogma, sometimes exaggerating flaws in early studies (e.g., Lewis Dahl’s rat experiments) or alleging conspiracies (e.g., pharmaceutical influence). More in Feyerabend’s view than in Kuhn’s, this exaggeration and rhetoric might be desirable. It’s useful. It provides the challenges that the paradigm should be able to overcome to remain dominant.

These challenges haven’t led to a paradigm shift yet, as the consensus remains robust, supported by RCTs and global health data. But they highlight the Kuhnian tension between entrenched views and emerging evidence, pushing science to refine its understanding.

Framing the issue as a contrarian challenge might go something like this:

Evidence-based medicine sets treatment guidelines, but evidence-based medicine has not translated into evidence-based policy. Governments advise lowering salt intake, but that advice is supported by little robust evidence for the general population. Randomized controlled trials have not strongly supported the benefit of salt reduction for average people. Indeed, we see evidence that low salt might pose as great a risk.

Methodological Challenges

The question “Is salt bad for you?” is ill-posed. Evidence and reasoning say this question oversimplifies a complex issue: sodium’s effects vary by individual (e.g., salt sensitivity, genetics), diet (e.g., processed vs. whole foods), and context (e.g., baseline blood pressure, activity level). Science doesn’t deliver binary truths. Modern science gives probabilistic models, refined through iterative testing.

While randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have shown that reducing sodium intake can lower blood pressure, especially in sensitive groups, observational studies show that extremely low sodium is associated with poor health. This association may signal reverse causality, an error in reasoning. The data may simply reveal that sicker people eat less, not that they are harmed by low salt. This complexity reflects the limitations of study design and the challenges of isolating causal relationships in real-world populations. The above graph is a fairly typical dose-response curve for any nutrient.

The salt debate also underscores the inherent difficulty of studying diet and health. Total caloric intake, physical activity, genetic variation, and compliance all confound the relationship between sodium and health outcomes. Few studies look at salt intake as a fraction of body weight. If sodium recommendations were expressed as sodium density (mg/kcal), it might help accommodate individual energy needs and eating patterns more effectively.

Science as an Iterative Process

Despite flaws in early studies and the polemics of dissenters, the scientific communities continue to refine its understanding. For example, Japan’s national sodium reduction efforts since the 1970s have coincided with significant declines in stroke mortality, suggesting real-world benefits to moderation, even if the exact causal mechanisms remain complex.

Through a Kuhnian lens, we see a dominant paradigm shaped by institutional consensus and refined by accumulating evidence. But we also see the system’s limits: anomalies, confounding variables, and methodological disputes that resist easy resolution.

Contrarians, though sometimes rhetorically provocative or methodologically uneven, play a crucial role. Like the “puzzle-solvers” and “revolutionaries” in Kuhn’s model, they pressure the scientific establishment to reexamine assumptions and tighten methods. This isn’t a flaw in science; it’s the process at work.

Salt isn’t simply “good” or “bad.” The better scientific question is more conditional: How does salt affect different individuals, in which contexts, and through what mechanisms? Answering this requires humility, robust methodology, and the acceptance that progress usually comes in increments. Science moves forward not despite uncertainty, disputation and contradiction but because of them.

After the Applause: Heilbron Rereads Feyerabend

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science, Philosophy of Science on June 4, 2025

A decade ago, in a Science, Technology and Society (STS) roundtable, I brought up Paul Feyerabend, who was certainly familiar to everyone present. I said that his demand for a separation of science and state – his call to keep science from becoming a tool of political authority – seemed newly relevant in the age of climate science and policy entanglement. Before I could finish the thought, someone cut in: “You can’t use Feyerabend to support republicanism!”

I hadn’t made an argument. Feyerabend was being claimed as someone who belonged to one side of a cultural war. His ideas were secondary. That moment stuck with me, not because I was misunderstood, but because Feyerabend was. And maybe he would have loved that. He was ambiguous by design. The trouble is that his deliberate opacity has hardened, over time, into distortion.

Feyerabend survives in fragments and footnotes. He’s the folk hero who overturned Method and danced on its ruins. He’s a cautionary tale: the man who gave license to science denial, epistemic relativism, and rhetorical chaos. You’ll find him invoked in cultural studies and critiques of scientific rationality, often with little more than the phrase “anything goes” as evidence. He’s also been called “the worst enemy of science.”

Against Method is remembered – or reviled – as a manifesto for intellectual anarchy. But “manifesto” doesn’t fit at all. It didn’t offer a vision, a list of principles, or a path forward. It has no normative component. It offered something stranger: a performance.

Feyerabend warned readers in the preface that the book would contradict itself, that it wasn’t impartial, and that it was meant to persuade, not instruct. He said – plainly and explicitly – that later parts would refute earlier ones. It was, in his words, a “tendentious” argument. And yet neither its admirers nor its critics have taken that warning seriously.

Against Method has become a kind of Rorschach test. For some, it’s license; for others, sabotage. Few ask what Feyerabend was really doing – or why he chose that method to attack Method. A few of us have long argued that Against Method has been misread. It was never meant as a guidebook or a threat, but as a theatrical critique staged to provoke and destabilize something that badly needed destabilizing.

That, I was pleased to learn, is also the argument made quietly and precisely in the last published work of historian John Heilbron. It may be the most honest reading of Feyerabend we’ve ever had.

John once told me that, unlike Kuhn, he had “the metabolism of a historian,” a phrase that struck me later as a perfect self-diagnosis: patient, skeptical, and slow-burning. He’d been at Berkeley when Feyerabend was still strutting the halls in full flair – the accent, the dramatic pronouncements, the partying. John didn’t much like him. He said so over lunch, on walks, at his house or mine. Feyerabend was hungry for applause, and John disapproved of his personal appetites and the way he flaunted them.

And yet… John’s recent piece on Feyerabend – the last thing he ever published – is microscopically delicate, charitable, and clear-eyed. John’s final chapter in Stefano Gattei’s recent book, Feyerabend in Dialogue, contains no score-settling, no demolition. Just a forensic mind trained to separate signal from noise. If Against Method is a performance, Heilbron doesn’t boo it offstage. He watches it again, closely, and tells us how it was done. Feyerabend through Heilbron’s lens is a performance reframed.

If anyone was positioned to make sense of Feyerabend, rhetorically, philosophically, and historically, it was Heilbron – Thomas Kuhn’s first graduate student, a lifelong physicist-turned-historian, and an expert on both early modern science and quantum theory’s conceptual tangles. His work on Galileo, Bohr, and the Scientific Revolution was always precise, occasionally sly, and never impressed by performance for performance’s sake.

That care is clearest in his treatment of Against Method’s most famous figure: Galileo. Feyerabend made Galileo the centerpiece of his case against scientific method – not as a heroic rationalist, but as a cunning rhetorician who won not because of superior evidence, but because of superior style. He compared Galileo to Goebbels, provocatively, to underscore how persuasion, not demonstration, drove the acceptance of heliocentrism. In Feyerabend’s hands, Galileo became a theatrical figure, a counterweight to the myth of Enlightenment rationality.

Heilbron dismantles this with the precision of someone who has lived in Galileo’s archives. He shows that while Galileo lacked a modern theory of optics, he was not blind to his telescope’s limits. He cross-checked, tested, and refined. He triangulated with terrestrial experiments. He understood that instruments could deceive, and worked around that risk with repetition and caution. The image of Galileo as a showman peddling illusions doesn’t hold up. Galileo, flaws acknowledged, was a working proto-scientist, attentive to the fragility of his tools.

Heilbron doesn’t mythologize Galileo; his 2010 Galileo makes that clear. But he rescues Galileo from Feyerabend’s caricature. In doing so, he models something Against Method never offered: a historically grounded, philosophically rigorous account of how science proceeds when tools are new, ideas unstable, and theory underdetermined by data.

To be clear, Galileo was no model of transparency. He framed the Dialogue as a contest between Copernicus and Ptolemy, though he knew Tycho Brahe’s hybrid system was the more serious rival. He pushed his theory of tides past what his evidence could support, ignoring counterarguments – even from Cardinal Bellarmine – and overstating the case for Earth’s motion.

Heilbron doesn’t conceal these. He details them, but not to dismiss. For him, these distortions are strategic flourishes – acts of navigation by someone operating at the edge of available proof. They’re rhetorical, yes, but grounded in observation, subject to revision, and paid for in methodological care.

That’s where the contrast with Feyerabend sharpens. Feyerabend used Galileo not to advance science, but to challenge its authority. More precisely, to challenge Method as the defining feature of science. His distortions – minimizing Galileo’s caution, questioning the telescope, reimagining inquiry as theater – were made not in pursuit of understanding, but in service of a larger philosophical provocation. This is the line Heilbron quietly draws: Galileo bent the rules to make a case about nature; Feyerabend bent the past to make a case about method.

In his final article, Heilbron makes four points. First, that the Galileo material in Against Method – its argumentative keystone – is historically slippery and intellectually inaccurate. Feyerabend downplays empirical discipline and treats rhetorical flourish as deception. Heilbron doesn’t call this dishonest. He calls it stagecraft.

Second, that Feyerabend’s grasp of classical mechanics, optics, and early astronomy was patchy. His critique of Galileo’s telescope rests on anachronistic assumptions about what Galileo “should have” known. He misses the trial-based, improvisational reasoning of early instrumental science. Heilbron restores that context.

Third, Heilbron credits Feyerabend’s early engagement with quantum mechanics – especially his critique of von Neumann’s no-hidden-variables proof and his alignment with David Bohm’s deterministic alternative. Feyerabend’s philosophical instincts were sharp.

And fourth, Heilbron tracks how Feyerabend’s stance unraveled – oscillating between admiration and disdain for Popper, Bohr, and even his earlier selves. He supported Bohm against Bohr in the 1950s, then defended Bohr against Popper in the 1970s. Heilbron doesn’t call this hypocrisy. He calls it instability built into the project itself: Feyerabend didn’t just critique rationalism – he acted out its undoing. If this sounds like a takedown, it isn’t. It’s a reconstruction – calm, slow, impartial. The rare sort that shows us not just what Feyerabend said, but where he came apart.

Heilbron reminds us what some have forgotten and many more never knew: that Feyerabend was once an insider. Before Against Method, he was embedded in the conceptual heart of quantum theory. He studied Bohm’s challenge to Copenhagen while at LSE, helped organize the 1957 Colston symposium in Bristol, and presented a paper there on quantum measurement theory. He stood among physicists of consequence – Bohr, Bohm, Podolsky, Rosen, Dirac, and Pauli – all struggling to articulate alternatives to an orthodoxy – Copenhagen Interpretation – that they found inadequate.

With typical wit, Heilbron notes that von Neumann’s no-hidden-variables proof “was widely believed, even by people who had read it.” Feyerabend saw that dogma was hiding inside the math – and tried to smoke it out.

Late in life, Feyerabend’s provocations would ripple outward in unexpected directions. In a 1990 lecture at Sapienza University, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger – later Pope Benedict XVI – quoted Against Method approvingly. He cited Feyerabend’s claim that the Church had been more reasonable than Galileo in the affair that defined their rupture. When Ratzinger’s 2008 return visit was canceled due to protests about that quotation, the irony was hard to miss. The Church, once accused of silencing science, was being silenced by it, and stood accused of quoting a philosopher who spent his life telling scientists to stop pretending they were priests.

We misunderstood Feyerabend not because he misled us, but because we failed to listen the way Heilbron did.

Anarchy and Its Discontents: Paul Feyerabend’s Critics

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science, Philosophy of Science on June 3, 2025

(For and against Against Method)

Paul Feyerabend’s 1975 Against Method and his related works made bold claims about the history of science, particularly the Galileo affair. He argued that science progressed not because of adherence to any specific method, but through what he called epistemological anarchism. He said that Galileo’s success was due in part to rhetoric, metaphor, and politics, not just evidence.

Some critics, especially physicists and historically rigorous philosophers of science, have pointed out technical and historical inaccuracies in Feyerabend’s treatment of physics. Here are some examples of the alleged errors and distortions:

Misunderstanding Inertial Frames in Galileo’s Defense of Copernicanism

Feyerabend argued that Galileo’s arguments for heliocentrism were not based on superior empirical evidence, and that Galileo used rhetorical tricks to win support. He claimed that Galileo simply lacked any means of distinguishing heliocentric from geocentric models empirically, so his arguments were no more rational than those of Tycho Brahe and other opponents.

His critics responded by saying that Galileo’s arguments based on the phases of Venus and Jupiter’s moons were empirically decisive against the Ptolemaic model. This is unarguable, though whether Galileo had empirical evidence to overthrow Tycho Brahe’s hybrid model is a much more nuanced matter.

Critics like Ronald Giere, John Worrall, and Alan Chalmers (What Is This Thing Called Science?) argued that Feyerabend underplayed how strong Galileo’s observational case actually was. They say Feyerabend confused the issue of whether Galileo had a conclusive argument with whether he had a better argument.

This warrants some unpacking. Specifically, what makes an argument – a model, a theory – better? Criteria might include:

- Empirical adequacy – Does the theory fit the data? (Bas van Fraassen)

- Simplicity – Does the theory avoid unnecessary complexity? (Carl Hempel)

- Coherence – Is it internally consistent? (Paul Thagard)

- Explanatory power – Does it explain more than rival theories? (Wesley Salmon)

- Predictive power – Does it generate testable predictions? (Karl Popper, Hempel)

- Fertility – Does it open new lines of research? (Lakatos)

Some argue that Galileo’s model (Copernicanism, heliocentrism) was obviously simpler than Brahe’s. But simplicity opens another can of philosophical worms. What counts as simple? Fewer entities? Fewer laws? More symmetry? Copernicus had simpler planetary order but required a moving Earth. And Copernicus still relied on epicycles, so heliocentrism wasn’t empirically simpler at first. Given the evidence of the time, a static Earth can be seen as simpler; you don’t need to explain the lack of wind and the “straight” path of falling bodies. Ultimately, this point boils down to aesthetics, not math or science. Galileo and later Newtonians valued mathematical elegance and unification. Aristotelians, the church, and Tychonians valued intuitive compatibility with observed motion.

Feyerabend also downplayed Galileo’s use of the principle of inertia, which was a major theoretical advance and central to explaining why we don’t feel the Earth’s motion.

Misuse of Optical Theory in the Case of Galileo’s Telescope

Feyerabend argued that Galileo’s use of the telescope was suspect because Galileo had no good optical theory and thus no firm epistemic ground for trusting what he saw.

His critics say that while Galileo didn’t have a fully developed geometrical optics theory (e.g., no wave theory of light), his empirical testing and calibration of the telescope were rigorous by the standards of the time.

Feyerabend is accused of anachronism – judging Galileo’s knowledge of optics by modern standards and therefore misrepresenting the robustness of his observational claims. Historians like Mario Biagioli and Stillman Drake point out that Galileo cross-verified telescope observations with the naked eye and used repetition, triangulation, and replication by others to build credibility.

Equating All Theories as Rhetorical Equals

Feyerabend in some parts of Against Method claimed that rival theories in the history of science were only judged superior in retrospect, and that even “inferior” theories like astrology or Aristotelian cosmology had equal rational footing at the time.

Historians like Steven Shapin (How to be Antiscientific) and David Wootton (The Invention of Science) say that this relativism erases real differences in how theories were judged even in Galileo’s time. While not elaborated in today’s language, Galileo and his rivals clearly saw predictive power, coherence, and observational support as fundamental criteria for choosing between theories.

Feyerabend’s polemical, theatrical tone often flattened the epistemic distinctions that working scientists and philosophers actually used, especially during the Scientific Revolution. His analysis of “anything goes” often ignored the actual disciplinary practices of science, especially in physics.

Failure to Grasp the Mathematical Structure of Physics

Scientists – those broad enough to know who Feyerabend was – often claim that he misunderstood or ignored the role of mathematics in theory-building, especially in Newtonian mechanics and post-Galilean developments. In Against Method, Feyerabend emphasizes metaphor and persuasion over mathematics. While this critique is valuable when aimed at the rhetorical and political sides of science, it underrates the internal mathematical constraints that shape physical theories, even for Galileo.

Imre Lakatos, his friend and critic, called Feyerabend’s work a form of “intellectual sabotage”, arguing that he distorted both the history and logic of physics.

Misrepresenting Quantum Mechanics

Feyerabend wrote about Bohr and Heisenberg in Philosophical Papers and later essays. Critics like Abner Shimony and Mario Bunge charge that Feyerabend misrepresented or misunderstood Bohr’s complementarity as relativistic, when Bohr’s position was more subtle and aimed at objective constraints on language and measurement.

Feyerabend certainly fails to understand the mathematical formalism underpinning Quantum Mechanics. This weakens his broader claims about theory incommensurability.

Feyerabend’s erroneous critique of Neil’s Bohr is seen in his 1958 Complimentarity:

“Bohr’s point of view may be introduced by saying that it is the exact opposite of [realism]. For Bohr the dual aspect of light and matter is not the deplorable consequence of the absence of a satisfactory theory, but a fundamental feature of the microscopic level. For him the existence of this feature indicates that we have to revise … the [realist] ideal of explanation.” (more on this in an upcoming post)

Epistemic Complaints

Beyond criticisms that he failed to grasp the relevant math and science, Feyerabend is accused of selectively reading or distorting historical episodes to fit the broader rhetorical point that science advances by breaking rules, and that no consistent method governs progress. Feyerabend’s claim that in science “anything goes” can be seen as epistemic relativism, leaving no rational basis to prefer one theory over another or to prefer science over astrology, myth, or pseudoscience.

Critics say Feyerabend blurred the distinction between how theories are argued (rhetoric) and how they are justified (epistemology). He is accused of conflating persuasive strategy with epistemic strength, thereby undermining the very principle of rational theory choice.

Some take this criticism to imply that methodological norms are the sole basis for theory choice. Feyerabend’s “anarchism” may demolish authority, but is anything left in its place except a vague appeal to democratic or cultural pluralism? Norman Levitt and Paul Gross, especially in Higher Superstition: The Academic Left and Its Quarrels with Science (1994), argue this point, along with saying Feyerabend attacked a caricature of science.

Personal note/commentary: In my view, Levitt and Gross did some great work, but Higher Superstition isn’t it. I bought the book shortly after its release because I was disgusted with weaponized academic anti-rationalism, postmodernism, relativism, and anti-science tendencies in the humanities, especially those that claimed to be scientific. I was sympathetic to Higher Superstition’s mission but, on reading it, was put off by its oversimplifications and lack of philosophical depth. Their arguments weren’t much better than those of the postmodernists. Critics of science in the humanities critics overreached and argued poorly, but they were responding to legitimate concerns in the philosophy of science. Specifically:

- Underdetermination – Two incompatible theories often fit the same data. Why do scientists prefer one over another? As Kuhn argued, social dynamics play a role.

- Theory-laden Observations – Observations are shaped by prior theory and assumptions, so science is not just “reading the book of nature.”

- Value-laden Theories – Public health metrics like life expectancy and morbidity (opposed to autonomy or quality of life) trickle into epidemiology.

- Historical Variability of Consensus – What’s considered rational or obvious changes over time (phlogiston, luminiferous ether, miasma theory).

- Institutional Interest and Incentives – String theory’s share of limited research funding, climate science in service of energy policy and social agenda.

- The Problem of Reification – IQ as a measure of intelligence has been reified in policy and education, despite deep theoretical and methodological debates about what it measures.

- Political or Ideological Capture – Marxist-Leninist science and eugenics were cases where ideology shaped what counted as science.

Higher Superstition and my unexpected negative reaction to it are what brought me to the discipline of History and Philosophy of Science.

Conclusion

Feyerabend exaggerated the uncertainty of early modern science, downplayed the empirical gains Galileo and others made, and misrepresented or misunderstood some of the technical content of physics. His mischievous rhetorical style made it hard to tell where serious argument ended and performance began. Rather than offering a coherent alternative methodology, Feyerabend’s value lay in exposing the fragility and contingency of scientific norms. He made it harder to treat methodological rules as timeless or universal by showing how easily they fracture under the pressure of real historical cases.

In a following post, I’ll review the last piece John Heilbron wrote before he died, Feyerabend, Bohr and Quantum Physics, which appeared in Stefano Gattei’s Feyerabend in Dialogue, a set of essays marking the 100th anniversary of Feyerabend’s birth.

Paul Feyerabend. Photo courtesy of Grazia Borrini-Feyerabend.

John Heilbron Interview – June 2012

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science, Philosophy of Science on June 2, 2025

In 2012, I spoke with John Heilbron, historian of science and Professor Emeritus at UC Berkeley, about his career, his work with Thomas Kuhn, and the legacy of The Structure of Scientific Revolutions on its 50th anniversary. We talked late into the night. The conversation covered his shift from physics to history, his encounters with Kuhn and Paul Feyerabend, and his critical take on the direction of Science and Technology Studies (STS).

The interview marked a key moment. Kuhn and Feyerabend’s legacies were under fresh scrutiny, and STS was in the midst of redefining itself, often leaning toward sociological frameworks at the expense of other approaches.

Thirteen years later, in 2025, this commentary revisits that interview to illuminate its historical context, situate Heilbron’s critiques, and explore their relevance to contemporary STS and broader academic debates.

Over more than a decade, I had ongoing conversations with Heilbron about the evolution of the history of science – history of the history of science – and the complex relationship between History of Science and Science, Technology, and Society (STS) programs. At UC Berkeley, unlike at Harvard or Stanford, STS has long remained a “Designated Emphasis” rather than a department or standalone degree. Academic conservatism in departmental structuring, concerns about reputational risk, and questions about the epistemic rigor of STS may all have contributed to this decision. Moreover, Berkeley already boasted world-class departments in both History and Sociology.

That 2012 interview, the only one we recorded, brought together themes we’d explored over many years. Since then, STS has moved closer to engaging with scientific content itself. But it still draws criticism, both from scientists and from public misunderstanding. In 2012, the field was still heavily influenced by sociological models, particularly the Strong Programme and social constructivism, which stressed how scientific knowledge is shaped by social context. One of the key texts in this tradition, Shapin and Schaffer’s Leviathan and the Air-Pump (1985), argued that even Boyle’s experiments weren’t simply about discovery but about constructing scientific consensus.

Heilbron pushed back against this framing. He believed it sidelined the technical and epistemic depth of science, reducing STS to a sociological critique. He was especially wary of the dense, abstract language common in constructivist work. In his view, it often served as cover for thin arguments, especially from younger scholars who copied the style but not the substance. He saw it as a tactic: establish control of the conversation by embedding a set of terms, then build influence from there.

The influence of Shapin and Schaffer, Heilbron argued, created the impression that STS was dominated by a single paradigm, ironically echoing the very Kuhnian framework they analyzed. His frustration with a then-recent Isis review reflected his concern that constructivism had become doctrinaire, pressuring scholars to conform to its methods even when irrelevant to their work. His reference to “political astuteness” pointed to the way in which key figures in the field successfully advanced their terminology and frameworks, gaining disproportionate influence. While this gave them intellectual clout, Heilbron saw it as a double-edged sword: it strengthened their position while encouraging dogmatism among followers who prioritized jargon over genuine analysis.

Bill Storage: How did you get started in this curious interdisciplinary academic realm?

John Heilbron: Well, it’s not really very interesting, but I was a graduate student in physics but my real interest was history. So at some point I went down to the History department and found the medievalist, because I wanted to do medieval history. I spoke with the medievalist ad he said, “well, that’s very charming but you know the country needs physicists and it doesn’t need medievalists, so why don’t you go back to physics.” Which I duly did. But he didn’t bother to point out that there was this guy Kuhn in the History department who had an entirely different take on the subject than he did. So finally I learned about Kuhn and went to see him. Since Kuhn had very few students, I looked good; and I gradually I worked my way free from the Physics department and went into history. My PhD is in History; and I took a lot history courses and, as I said, history really is my interest. I’m interested in science too of course but I feel that my major concerns are historical and the writing of history is to me much more interesting and pleasant than calculations.

You entered that world at a fascinating time, when history of science – I’m sure to the surprise of most of its scholars – exploded onto the popular scene. Kuhn, Popper, Feyerabend and Lakatos suddenly appeared in The New Yorker, Life Magazine, and The Christian Century. I find that these guys are still being read, misread and misunderstood by many audiences. And that seems to be true even for their intended audiences – sometimes by philosophers and historians of science – certainly by scientists. I see multiple conflicting readings that would seem to show that at least some of them are wrong.

Well if you have two or more different readings then I guess that’s a safe conclusion. (Laughs.)

You have a problem with multiple conflicting truths…? Anyway – misreading Kuhn…

I’m more familiar with the misreading of Kuhn than of the others. I’m familiar with that because he was himself very distressed by many of the uses made of his work – particularly the notion that science is no different from art or has no stronger basis than opinion. And that bothered him a lot.

I don’t know your involvement in his work around that time. Can you tell me how you relate to what he was doing in that era?

I got my PhD under him. In fact my first work with him was hunting up footnotes for Structure. So I knew the text of the final draft well – and I knew him quite well during the initial reception of it. And then we all went off together to Copenhagen for a physics project and we were all thrown together a lot. So that was my personal connection and then of course I’ve been interested subsequently in Structure, as everybody is bound to be in my line of work. So there’s no doubt, as he says so in several places, that he was distressed by the uses made of it. And that includes uses made in the history of science particularly by the social constructionists, who try to do without science altogether or rather just to make it epiphenomenal on political or social forces.

I’ve read opinions by others who were connected with Kuhn saying there was a degree of back-peddling going by Kuhn in the 1970s. The implication there is that he really did intend more sociological commentary than he later claimed. Now I don’t see evidence of that in the text of Structure, and incidents like his telling Freeman Dyson that he (Kuhn) was not a Kuhnian would suggest otherwise. Do you have any thoughts on that?

I think that one should keep in mind the purpose of Structure, or rather the context in which it was produced. It was supposed to have been an article in this encyclopedia of unified science and Kuhn’s main interest was in correcting philosophers. He was not aiming for historians even. His message was that the philosophy practiced by a lot of positivists and their description of science was ridiculous because it didn’t pay any attention to the way science was actually done. So Kuhn was going to tell them how science was done, in order to correct philosophy. But then much to his surprise he got picked up by people for whom it was not written, who derived from it the social constructionist lesson that we’re all familiar with. And that’s why he was an unexpected rebel. But he did expect to be rebellious; that was the whole point. It’s just that the object of his rebellion was not history or science but philosophy.

So in that sense it would seem that Feyerabend’s question on whether Kuhn intended to be prescriptive versus descriptive is answered. It was not prescriptive.

Right – not prescriptive to scientists. But it was meant to be prescriptive to the philosophers – or at least normalizing – so that they would stop being silly and would base their conception of scientific progress on the way in which scientists actually went about their business. But then the whole thing got too big for him and he got into things that, in my opinion, really don’t have anything to do with his main argument. For example, the notion of incommensurability, which was not, it seems to me, in the original program. And it’s a logical construct that I don’t think is really very helpful, and he got quite hung up on that and seemed to regard that as the most important philosophical message from Structure.

I wasn’t aware that he saw it that way. I’m aware that quite a few others viewed it like that. Paul Feyerabend, in one of his last books, said that he and Kuhn kicked around this idea of commensurability in 1960 and had slightly different ideas about where to go with it. Feyerabend said Kuhn wanted to use it historically whereas his usage was much more abstract. I was surprised at the level of collaboration indicated by Feyerabend.

Well they talked a lot. They were colleagues. I remember parties at Kuhn’s house where Feyerabend would show up with his old white T shirt and several women – but that’s perhaps irrelevant to the main discussion. They were good friends. I got along quite well with Feyerabend too. We had discussions about the history of quantum physics and so on. The published correspondence between Feyerabend and Lakatos is relevant here. It’s rather interesting in that the person we’ve left out of the discussion so far, Karl Popper, was really the lighthouse for Feyerabend and Lakatos, but not for Kuhn. And I think that anybody who wants to get to the bottom of the relationship between Kuhn and Feyerabend needs to consider the guy out of the frame, who is Popper.

It appears Feyerabend was very critical of Kuhn and Structure at the time it was published. I think at that point Feyerabend was still essentially a Popperian. It seems Feyerabend reversed position on that over the next decade or so.

JH: Yes, at the time in question, around 1960, when they had these discussions, I think Feyerabend was still very much in Popper’s camp. Of course like any bright student, he disagreed with his professor about things.

How about you, as a bright student in 1960 – what did you disagree with your professor, Kuhn, about?

Well I believe in the proposition that philosophers and historians have different metabolisms. And I’m metabolically a historian and Kuhn was metabolically a philosopher – even though he did write history. But his most sustained piece of history of science was his book on black body theory; and that’s very narrowly intellectualist in approach. It’s got nothing to do with the themes of the structure of scientific revolutions – which does have something to say for the historian – but he was not by practice a historian. He didn’t like a whole lot of contingent facts. He didn’t like archival and library work. His notion of fun was take a few texts and just analyze and reanalyze them until he felt he had worked his way into the mind of their author. I take that to be a necromantic feat that’s not really possible.

I found that he was a very clever guy and he was excellent as a professor because he was very interested in what you were doing as soon it was something he thought he could make some use of. And that gave you the idea that you were engaged in something important, so I must give him that. On the other hand he just didn’t have the instincts or the knowledge to be a historian and so I found myself not taking much from his own examples. Once I had an argument with him about some way of treating a historical subject and I didn’t feel that I got anything out of him. Quite the contrary; I thought that he just ducked all the interesting issues. But that was because they didn’t concern him.

James Conant, president of Harvard who banned communists, chair of the National Science Foundation, etc.: how about Conant’s influence on Structure?

It’s not just Conant. It was the whole Harvard circle, of which Kuhn was part. There was this guy, Leonard Nash; there was Gerald Holton. And these guys would get together and l talk about various things having to do with the relationship between science and the public sphere. It was a time when Conant was fighting for the National Science Foundation and I think that this notion of “normal science” in which the scientists themselves must be left fully in charge of what they’re doing in order to maximize the progress within the paradigm to bring the profession swiftly to the next revolution – that this is essentially the Conant doctrine with respect to the ground rules of the National Science Foundation, which is “let the scientists run it.” So all those things were discussed. And you can find many bits of Kuhn’s Structure in that discussion. For example, the orthodoxy of normal science in, say, Bernard Cohen, who didn’t make anything of it of course. So there’s a lot of this Harvard group in Structure, as well as certain lessons that Kuhn took from his book on the Copernican Revolution, which was the textbook for the course he gave under Conant. So yes, I think Conant’s influence is very strong there.

So Kuhn was ultimately a philosopher where you are a historian. I think I once heard you say that reading historical documents does not give you history.

Well I agree with that, but I don’t remember that I was clever enough to say it.

Assuming you said it or believe it, then what does give you history?

Well, reading them is essential, but the part contributed by the historian is to make some sense of all the waste paper he’s been reading. This is essentially a construction. And that’s where the art, the science, the technique of the historian comes into play, to try to make a plausible narrative that has to satisfy certain rules. It can’t go against the known facts and it can’t ignore the new facts that have come to light through the study of this waste paper, and it can’t violate rules of verisimilitude, human action and whatnot. But otherwise it’s a construction and you’re free to manipulate your characters, and that’s what I like about it.

So I take it that’s where the historian’s metabolism comes into play – avoidance of leaping to conclusions with the facts.

True, but at some point you’ve got to make up a story about those facts.

Ok, I’ve got a couple questions on the present state of affairs – and this is still related to the aftermath of Kuhn. From attending colloquia, I sense that STS is nearly a euphemism for sociology of science. That bothers me a bit, possibly because I’m interested in the intersection of science, technology and society. Looking at the core STS requirements on Stanford’s website, I see few courses listed that would give a student any hint of what science looks like from the inside.

I’m afraid you’re only too right. I’ve got nothing against sociology of science, the study of scientific institutions, etc. They’re all very good. But they’re tending to leave the science out, and in my opinion, the further they get from science, the worse their arguments become. That’s what bothers me perhaps most of all – the weakness of the evidentiary base of many of the arguments and conclusions that are put forward.

I thought we all learned a bit from the Science Wars – thought that sort of indeterminacy of meaning and obfuscatory language was behind us. Either it’s back, or it never went away.

Yeah, the language part is an important aspect of it, and even when the language is relatively comprehensible as I think it is in, say, constructivist history of science – by which I mean the school of Schaffer and Shapin – the insistence on peculiar argot becomes a substitute for thought. You see it quite frequently in people less able than those two guys are, who try to follow in their footsteps. You get words strung together supposedly constituting an argument but which in fact don’t. I find that quite an interesting aspect of the business, and very astute politically on the part of those guys because if you can get your words into the discourse, why, you can still hope to have influence. There’s a doctrinaire aspect to it. I was just reading the current ISIS favorable book review by one of the fellow travelers of this group. The book was not written by one of them. The review was rather complimentary but then at the end says it is a shame that this author did not discuss her views as related to Schaffer and Shapin. Well, why the devil should she? So, yes, there’s issues of language, authority, and poor argumentation. STS is afflicted by this, no doubt.

Dialogue Concerning a Cup of Cooked Collards

Posted by Bill Storage in Fiction, History of Science on May 27, 2025

in which the estimable Signora Sagreda, guided by the lucid reasoning of Salviatus and the amiable perplexities of Simplicius, doth inquire into the nature of culinary measurement, and wherein is revealed, by turns comic and calamitous, the logical dilemma and profound absurdity of quantifying cooked collards by volume, exposing thereby the nutritional fallacies, atomic impossibilities, and epistemic mischiefs that attend such a practice, whilst invoking with reverence the spectral wisdom of Galileo Galilei.

Scene: A modest parlor, with a view into a well-appointed kitchen. A pot of collards simmers.

Sagreda: Good sirs, I am in possession of a recipe, inherited from a venerable aunt, which instructs me to add one cup of cooked collards to the dish. Yet I find myself arrested by perplexity. How, I ask, can one trust such a measure, given the capricious nature of leaves once cooked?

Salviatus: Ah, Signora, thou hast struck upon a question of more gravity than may at first appear. In that innocent-seeming phrase lies the germ of chaos, the undoing of proportion, and the betrayal of consistency.

Simplicius: But surely, Salviatus, a cup is a cup! Whether one deals with molasses, barley, or leaves of collard! The vessel measures equal, does it not?

Salviatus: Ah, dear Simplicius, how quaint thy faith in vessels. Permit me to elaborate with the fullness this foolishness begs. A cup, as used here, is a measure of volume, not mass. Yet collards, when cooked, submit themselves to the will of the physics most violently. One might say that a plenty of raw collards, verdant and voluminous, upon the fire becomes but a soggy testament to entropy.

Sagreda: And yet if I, with ladle in hand, press them lightly, I may fill a cup with tender grace. But if I should tamp them down, as a banker tamps tobacco, I might squeeze thrice more into the same vessel.

Salviatus: Just so! And here lies its absurdity. The recipe calls for a cup, as though the collards were flour, or water, or some polite ingredient that hold the law of uniformity. But collards — and forgive my speaking plainly — are rogues. One cook’s gentle heap is another’s aggressive compression. Thus, a recipe using such a measure becomes not a method, but a riddle, a culinary Sphinx.

Simplicius: But might not tradition account for this? For is it not the case that housewives and cooks of yore prepared these dishes with their senses and not with scales?