Posts Tagged history

Robert Reich, Genius

Posted by Bill Storage in Commentary on December 25, 2025

Is Robert Reich a twit, or does he just play one for money on the internet?

I never cared about Monica Lewinsky. Bill Clinton was a big-picture sort of president, like Ronald Reagan, oddly. Flawed personally, but who are we to be critical? Marriage to Hillary might test anyone’s resolve with cigars and Big Macs. Yet somehow Clinton elevated Robert Reich to Secretary of Labor. Maybe he thought Panetta and Greenspan could keep the ideologue in check.

Reich later resigned and penned Locked in the Cabinet, a “memoir” devoured by left-wing academics despite its fabricated dialogues – proven mismatches with transcripts and C-SPAN tapes. Facts are optional when the narrative sings.

Fast-forward: Reich posted this on December 23:

“Around 70% of the U.S. economy depends on consumer spending. As wealth concentrates in the richest 10%, the rest of America can’t afford to buy enough to keep the economy running.”

Classic Reich: tidy slogan, profound vibe, zero nuance, preached to the CNN faithful.

Yes, consumption is ~70% of GDP. But accounting isn’t causation. Saying the economy “runs on” consumption is like saying a car runs on exhaust because that’s what comes out the back.

Wealth concentration doesn’t vanish spending:

- High earners save more per dollar, true – but they do spend (luxury, services) and, crucially, invest.

- Investment isn’t hoarded in vaults; it funds factories, tech, startups, real estate – creating jobs and future demand. U.S. history proves inequality and growth coexist.

- The economy isn’t a closed moral ecosystem: Government spending, exports, debt expansion, asset bubbles, and credit substitution all prop things up, sometimes for a long time and sometimes disastrously. Reich’s “can’t afford” is doing heroic rhetorical labor here.

Reich smuggles in a fixed “enough” consumption – for full employment? Asset bubbles? Entitlements? That’s the debate, not premise.

His real point is political: Extreme inequality risks instability in a consumption-heavy model. Fair to argue. But he serves it as revealed truth, as if Keynes himself chiseled it.

Reich champions “labor and farmers” while blaming Trump’s tariffs for the price of beef. Thank you Robert, but, as Deming argued (unsuccessfully) to US auto makers, some people will pay more for quality. Detroit disagreed, and Toyota cleaned their clocks. Yes, I’m willing to pay more for local beef. I’m sure Bill Clinton would, had he not gone all vegan on us. Moderation, Bill, like Groucho said about his cigar.

Reich’s got bumper-sticker economics. Feels good, thinks shallow.

Lawlessness Is a Choice, Bugliosi Style

Posted by Bill Storage in Commentary on December 8, 2025

Sloppiness is a choice. Miranda Devine’s essay, Lawlessness Is a Choice, in the October Imprimis is a furious and wordy indictment of progressive criminal-justice policies. Its central claim is valid enough: rising crime in Democratic cities is a deliberate ideological choice. Her piece has two fatal defects, at least from the perspective of a class I’m taking on on persuasive writing. Her piece is argued badly, written worse. Vincent Bugliosi, who prosecuted Charles Manson, comes to mind – specifically, the point made in Outrage, his book about the OJ Simpson trial. Throwing 100 points at the wall dares your opponent to knock down the three weakest, handing them an apparent victory over the entire case.

Devine repeats “lawlessness is a choice” until it sounds like a car alarm. She careens from New York bail reform to Venezuelan gangs to Antifa assassination. Anecdotes are piled on statistics piled on sarcasm until you’re buried under heap of steaming right-wing indignation.

Opponents are “nutty,” “deranged,” “unhinged,” or “turkeys who voted for Thanksgiving.” 20 to 25 million “imported criminals.” Marijuana is the harbinger of civilizational collapse. Blue-city prosecutors personally orchestrate subway assaults. Devine violates Bugliosi’s dictum throughout.

Easily shredded claims:

- Unsourced assertions of “20-25 million imported criminals.”

- Blanket opposition to marijuana decriminalization, conflating licensed dispensaries with open-air drug markets and public defecation as equally obvious “broken windows” offenses, even though two-thirds of Americans now support legal pot and several red states have thriving regulated markets.

- Stating that Antifa was plotting to assassinate Trump with no citation.

- Ignoring red-state violent-crime rates that sometimes exceed those of the blue cities she condemns.

A competent MSNBC segment producer – there may be one for all I know – could demolish the above in five minutes and then declare Devine’s whole law-and-order critique “conspiracy theory.” The stronger arguments – recidivism under New York’s bail reform, collapse of subway policing after 2020, the chilling effect of the Daniel Penny prosecution, the measurable crime drop after Trump’s 2025 D.C. National Guard deployment – are drowned in the noise.

The tragedy is that Devine is mostly right. Progressive reforms since 2020 (no-cash bail with no risk assessment, de facto decriminalization of shoplifting under $950, deliberate non-enforcement of quality-of-life offenses) have produced predictable disorder. The refusal of elite progressive voices to acknowledge personal agency is corrosive.

Bugliosi would choose his ground and his numbers carefully, conceding obvious points (red states have violent crime too), He wouldn’t be temped to merge every culture-war grievance. Devine chose poorly, and will persuade no one who matters. Now if Bugliosi had written it…

Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, the defense will tell you that crime spikes in American cities are complicated – poverty, guns, COVID, racism, underfunding. I lay out five undisputed facts, that in the years 2020–2024 major Democratic cities deliberately chose policies that produced disorder. They were warned. When the predicted outcome happened, they denied responsibility. That is not complexity but choice.

Count 1 – New York’s bail reform (2019–2020): The law eliminated cash bail for most misdemeanors and non-violent felonies, and required judges to release defendants with the “least restrictive” conditions. Funding was unchanged. Result: 2020-2023 saw over 10,000 rearrests of people released under the new law for new felonies while awaiting. In 2022 alone, at least 107 people released under bail reform were rearrested for murder or attempted murder. The legislature was warned. They passed it anyway. Choice.

Count 2 – Subway policing collapse: In January 2020 the NYPD had 2,500 uniformed officers assigned to the subway system. By late 2022 it was under 1,000. Felony assaults in the subway system rose 53 % from 2019 to 2023. This was deliberate de-policing ordered by City Hall and the Manhattan DA. Choice.

Count 3 – San Francisco’s Prop 47 and the $950 rule: California reclassified theft under $950 as a misdemeanor. Shoplifting reports in San Francisco rose 300%. Chain pharmacies closed 20 stores, citing unsustainable theft. The legislature refused every attempt to raise the threshold or mandate prosecution. Choice.

Count 4 – The Daniel Penny prosecution: Marine veteran Daniel Penny restrains a man who was screaming threats on a subway car. The man dies. Manhattan DA Alvin Bragg charges Penny with manslaughter. After two years of trial and massive expense, a jury acquits on the top count and deadlocks on the lesser; Bragg drops the case. Message sent: if you intervene to protect others, you roll the dice on court and possible prison. That chilling effect was the entire point of the prosecution. Choice.

Count 5 – The 2025 Washington, D.C. experiment: President Trump federalizes the D.C. National Guard and surges 3,000 troops plus federal agents into high-crime areas. Result in first 100 days: carjackings down 82%, homicides down 41%, robberies down 31% No gun buybacks – just enforcement. When the policy is reversed by court order, the numbers rose again within weeks. Enforcement works; the absence of enforcement is a choice.

Five exhibits, all public record. No unsourced 25-million-migrant claims, no Antifa conspiracy theories, nothing about Colorado potheads. Five policy decisions, five warnings ignored, five measurable explosions in disorder, and one rapid reversal when enforcement returned.

The defense will now tell you all about root causes. But I remind you that no city was forced to remove all consequences for criminal behavior. They were warned. They chose. They own the results. Lawlessness is a choice.

It’s the Losers Who Write History

Posted by Bill Storage in Commentary on November 24, 2025

The victors write first drafts. They get to seize archives, commission official chronicles, destroy inconvenient records, and shape the immediate public memory. Take Roman accounts of Carthage and Spanish on the Aztecs. What happens afterward and indefinitely is where Humanities departments play an outsized role in canonization.

Such academics are the relativist high priests of the safe-space seminary – tenured custodians of western-cultural suicide. Their scripture is the ever-shifting DEI bulletin. Credentialed barbarians stand behind at the gates they themselves dismantled. They are moral vacationers who turned the university into a daycare for perpetual adolescents. The new scholastic is the aristocracy of mediocrity. Historicist gravediggers have pronouncing the West dead so they can inherit its estate.

Several mechanisms make this possible. Academic historians, not primary sources – whether Cicero or Churchill – decide which questions are worth asking. Since the 1970s especially, new methodologies like social history, postcolonial studies, gender studies, and critical race theory have systematically shifted focus away from political, military, and diplomatic chronicling toward power structures, marginalized voices, and systemic oppression. These are not neutral shifts. They reflect the political priorities of the post-Nixon academic left, which has dominated western humanities departments since.

Peer-reviewed journals, university presses, hiring committees, and tenure standards are overwhelmingly controlled by scholars who share an ideological range scarcely wider than a breath. Studies of political self-identification among historians routinely show ratios of 20:1 or higher in favor of the left – often contented Marxists. Dissenting or traditional interpretations that challenge revisionist views on colonialism, the Soviet Union, or America’s founding are marginalized, denied publication, and labeled “problematic.” A career is erased overnight.

K-12 and undergraduate curricula worship academic consensus. Here, again, is a coherence theory of truth subjugating the correspondence model. When the consensus changes – when a critical mass of scholars finds an even more apologetic lens – textbooks follow, almost instantly. The portrayal of the European Age of Exploration, for example, went overnight from celebration of discovery to exclusive emphasis on conquest and genocide. American Founding Fathers went from flawed but visionary innovators of a unique government to rich slave-owning hypocrites, especially after the 1619 Project gained academic traction. A generation or two of Humanities college grads have no clue that “rich white man” Alexander Hamilton was born illegitimate in the Caribbean, was a lifelong unambiguous abolitionist, despised the slave-based Southern economic model, and died broke. They don’t know that the atheist Gouverneur Morris at the Constitutional Convention called slavery “a nefarious institution … the curse of heaven on the states where it prevailed.” They don’t know this because they’ve never heard of Gouverneur Morris, the author of the final draft of the Constitution. That’s because Ken Burns never mentions Morris in his histories. It doesn’t fit his caricature. Ken Burns is where intellectuals learn history. His The Vietnam War is assigned in thousands of high-school and college courses as authoritative history.

Modern historians openly admit that they mean their work to serve social justice goals. The past is mined for precedents, cautionary tales, or moral leverage rather than reconstructed for its own sake. The American Historical Association’s own statements have emphasized “reckoning with the past” in explicitly activist language. Howard Zinn (A People’s History of the United States) boasted, “I don’t pretend to be neutral.”

The academic elite – professional mourners at the funeral of the mind they themselves poisoned – have graduated an entire generation who believe Nixon escalated (if not started) the Vietnam War. This is a textbook (literally) case of the academic apparatus quietly rewriting the emphasis of history. Safe-space sommeliers surely have access to original historical data, but their sheep are too docile to demand primary sources. Instead, border patrollers of the settler-colonial imagination serve up moral panic by the pronoun to their trauma-informed flock.

The numbers. Troop levels went from 1000 when Kennedy took office to 184,000 in 1965 under Johnson. A year later they hit 385,000, and peaked at 543,000 when Nixon took office in 1969. Nixon’s actual policy was systematic de-escalation; he reduced US troops to 24,000 by early 1973, then withdrew the U.S. from ground combat in March. But widely used texts like The American Pageant, Nation of Nations, and Visions of America ignore Kennedy’s and Johnson’s role while framing Nixon as the primary villain of the war. And a large fraction of the therapeutic sheep with Che Guevara posters in their dorms graze contentedly inside an electric fence of approved opinions. They genuinely believe Nixon started Vietnam, and they’re happy with that belief.

If Allan Bloom – the liberal Democrat author of The Closing of the American Mind (1987) – were somehow resurrected in 2025 and lived through the Great Awokening, I suspect he’d swing pretty far into the counter-revolutionary space of Victor Davis Hanson. He’d scorch the vanguardist curators of the neopuritan archival gaze and their pronoun-pious lambs who bleat “decolonize” while paying $100K a year to be colonized by the university’s endowment.

Ken Burns said he sees cuts to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting as a serious existential threat. He did. The republic – which he calls a democracy – is oh so fragile. He speaks as though he alone has been appointed to heal America’s soul. It’s the same sacerdotal NPR manner that Bloom skewered in the humanities professoriate: the priestly conviction that one is engaged in something higher than mere scholarship, something redemptive. And the nation keeps paying Burns for it, because it’s so much more comfortable to cry over a Burns film than to wrestle with the actual complexity Burns quietly edits out. He’s not a historian. He’s the high priest of the officially sanctioned memory palace. It’s losers like Burns who write history.

Things to See in Palazzo Massimo

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Art, History of Christianity on November 10, 2025

Mike and Andrea visit Rome this week. Here’s what I think they should see in Museo Nazionale Romano, Palazzo Massimo. Not that I’d try to push my taste on anyone.

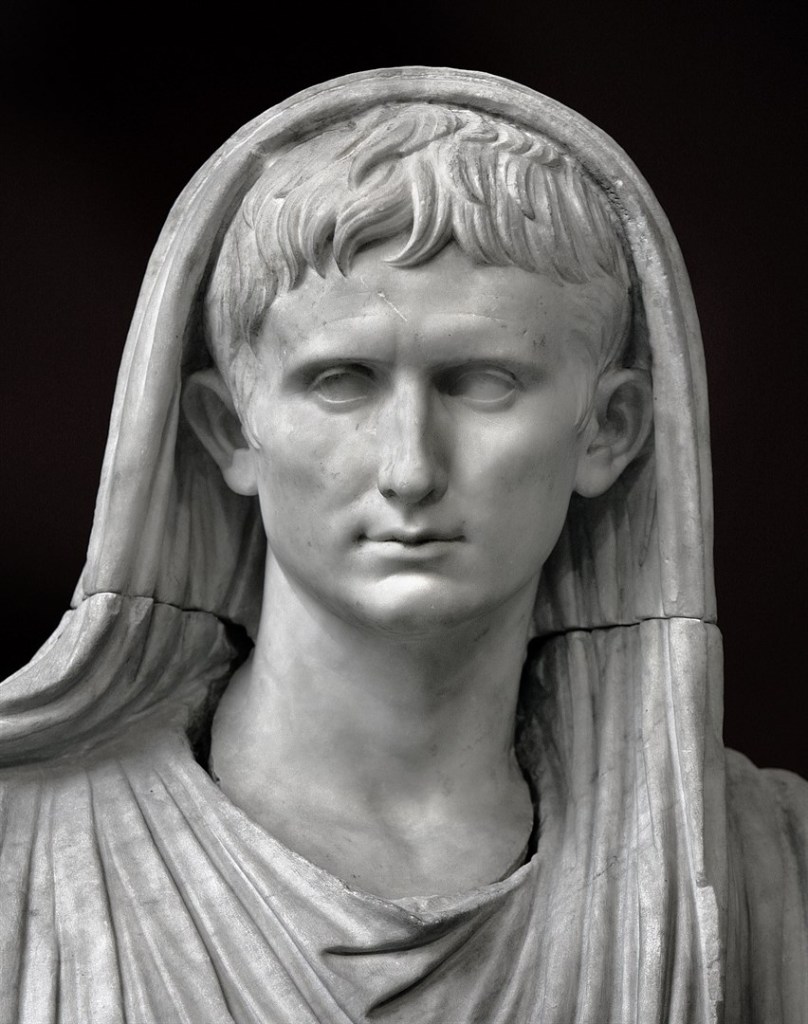

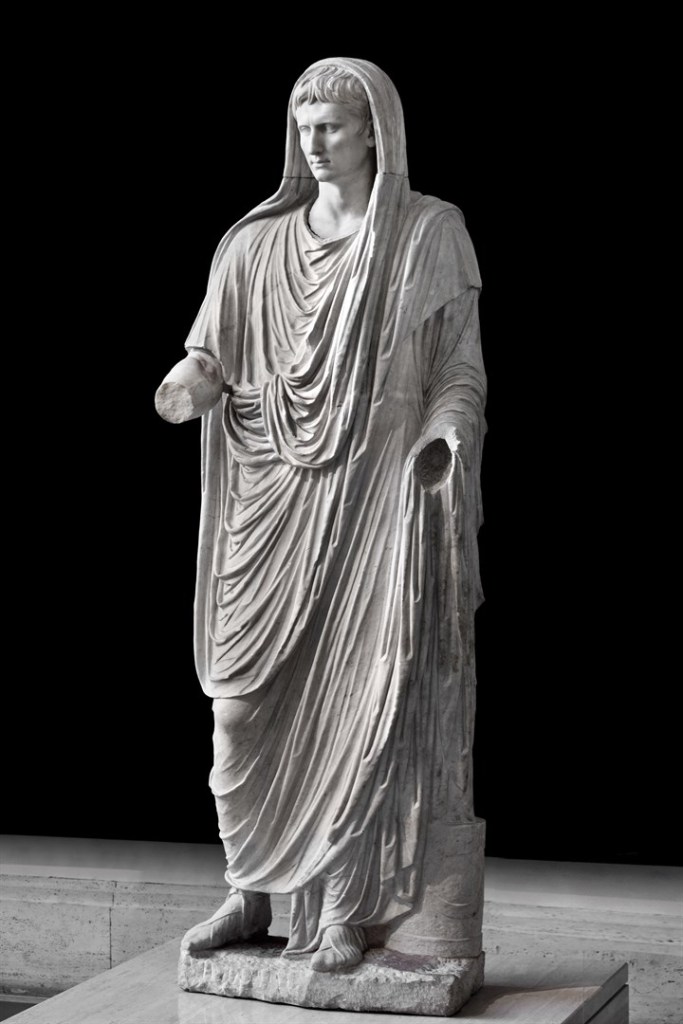

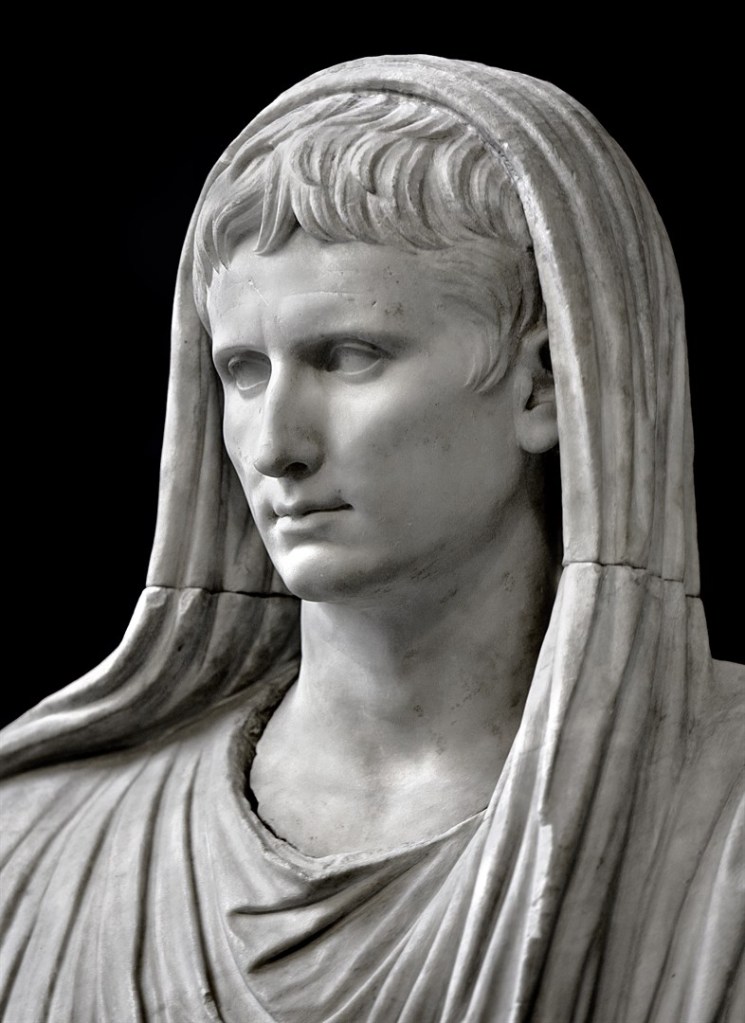

The Via Labicana Augustus

The Via Labicana Augustus was discovered in 1910 near the Via Labicana, southeast of Rome. It probably dates to 12 BCE, the year Augustus became Pontifex Maximus, chief priest of Rome.

The statue shows him veiled, performing a sacrifice, wearing the toga pulled over his head in the ritual gesture known as capite velato. Unlike the heroic, idealized Augustus of Prima Porta, this image presents him not as a godlike conqueror but as the pious restorer of Rome’s religious traditions. The face retains a calm, idealized realism – a softened continuation of late Republican verism – while the body’s smooth drapery and composed stance convey dignity and divine favor.

The piece reveals Augustus’s political strategy of merging personal authority with religious legitimacy. By showing himself as priest rather than warrior, he presented his rule as moral renewal and continuity with the Republic’s sacred traditions, rather than naked monarchy.

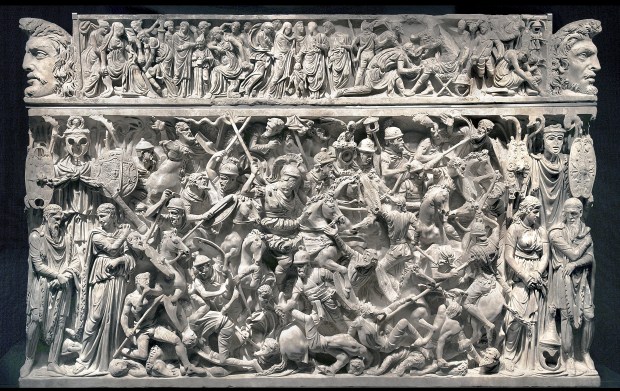

The Portonaccio Sarcophagus

The Portonaccio Sarcophagus, carved in high relief around 180-190 CE, is one of the most elaborate Roman sarcophagi from the late second century CE. It was discovered in a tomb in 1931 near the ancient Via Tiburtina in the Portonaccio area of Rome.

The front is a dense, chaotic battle scene. Roman soldiers clash with barbarians in a tangle of limbs, shields, and horses. There’s no clear spatial depth, just a frenzied mass of combat, carved almost in relief upon relief. At the center stands the Roman general, larger and calmer than the rest, commanding order amid chaos. His face is idealized, yet individualized; his bare head suggests he may have died before receiving a victory crown.

This style marks a shift from the classical order of earlier art to the expressive, almost abstract energy of late imperial sculpture. It reflects the constant warfare and political instability of the era. It likely commemorated General Aulus Iulius Pompilius, who served under Marcus Aurelius.

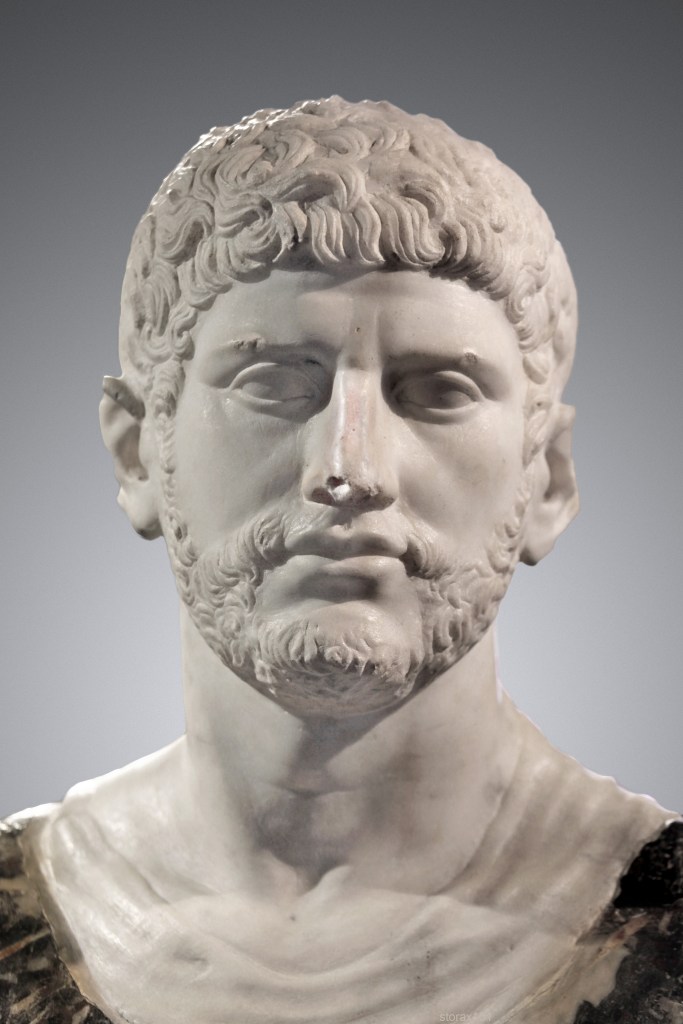

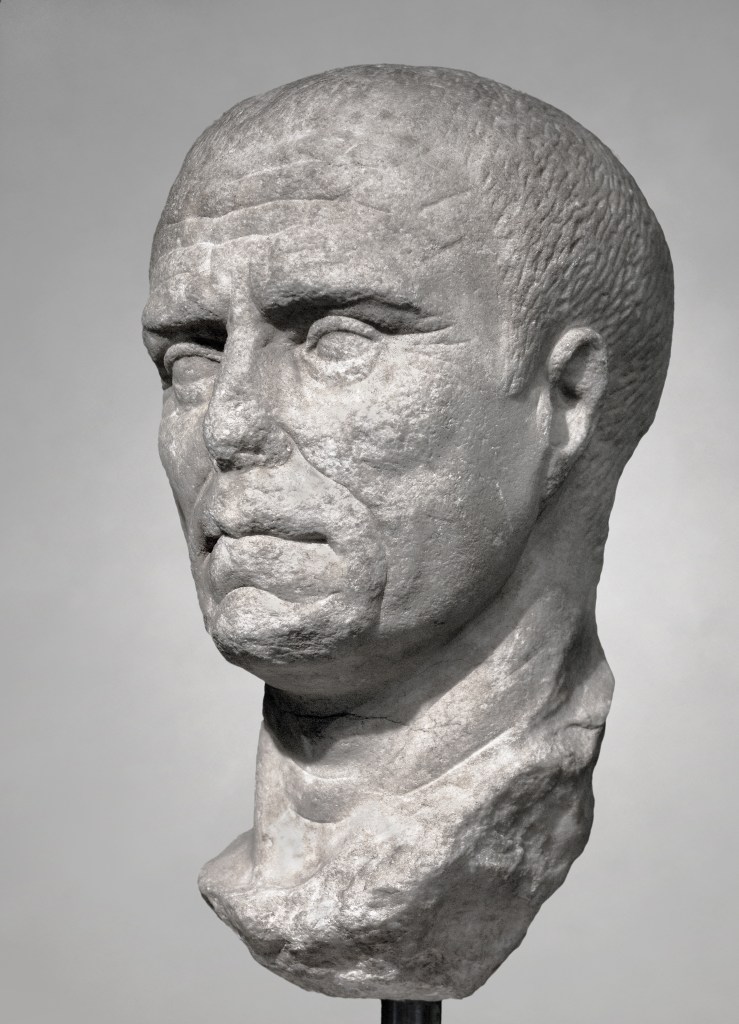

Colossal Bust of Gordian III

The colossal marble bust of Gordian III presents a striking – if not bizarre – image of the boy-emperor struggling to embody imperial gravitas. Created around AD 244, it reflects the tension between youthful vulnerability and the formal ideals of Roman authority.

Gordian III came to the throne after a cascade of assassinations during the “Year of the Six Emperors.” The sculptor has rendered him with the smooth, unlined face of an adolescent, but framed by the austere, hieratic composition typical of imperial portraiture – short military haircut, heavy-lidded eyes gazing slightly upward, and a thick neck suggesting strength he did could not have possessed. The result is almost tragic: the image insists on imperial permanence while hinting at fragility.

Stylistically, the bust belongs to the late Severan, early soldier-emperor phase, where portraiture shifts from the individualized realism of the Antonines to a more schematic, abstract treatment of features. The deep drilling of the hair and the intense, static expression anticipate the hard linearity of third-century imperial art.

The Charioteers

The charioteer portrait busts date from the early fourth century CE and depict professional aurigae – chariot racers who were the sports celebrities of late imperial Rome.

These busts show men with distinctive attributes of their trade: short, tightly curled hair, intense gazes, and tunics bound with leather straps across the chest, used to secure their protective harnesses during races. The faces are individualized, confident, and slightly idealized, conveying both athletic vigor and the proud self-awareness of public fame.

They likely commemorated successful drivers from the great Roman circuses, perhaps freedmen who had risen to wealth and status through racing. The style, with its crisp carving and alert expression, reflects late Roman portraiture’s mix of realism and formal abstraction – an art no longer concerned with classical balance, but with projecting charisma and presence.

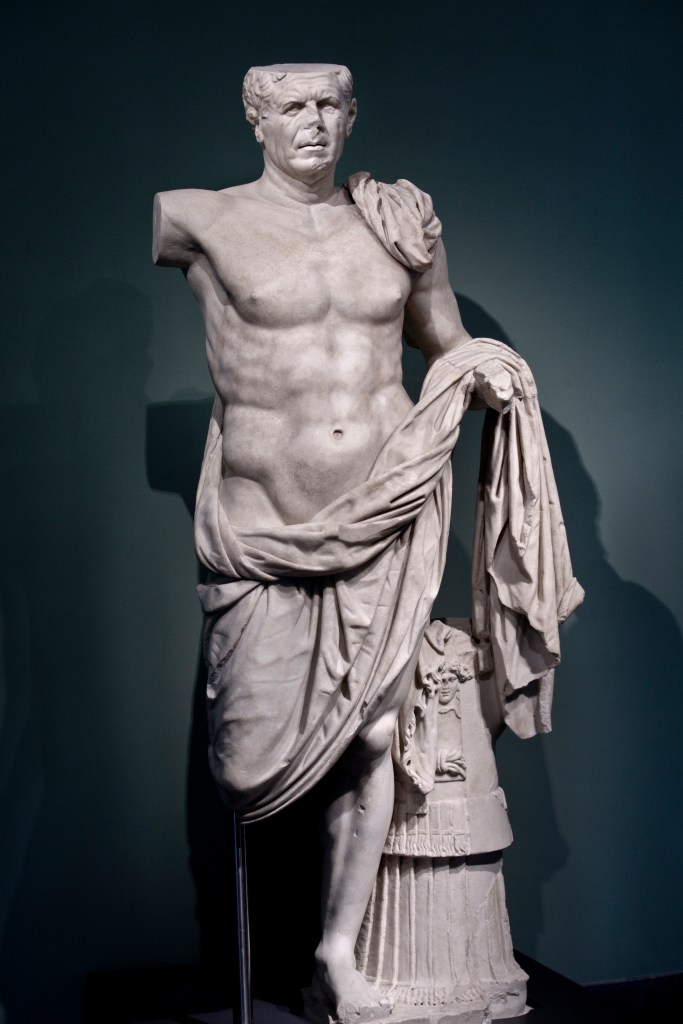

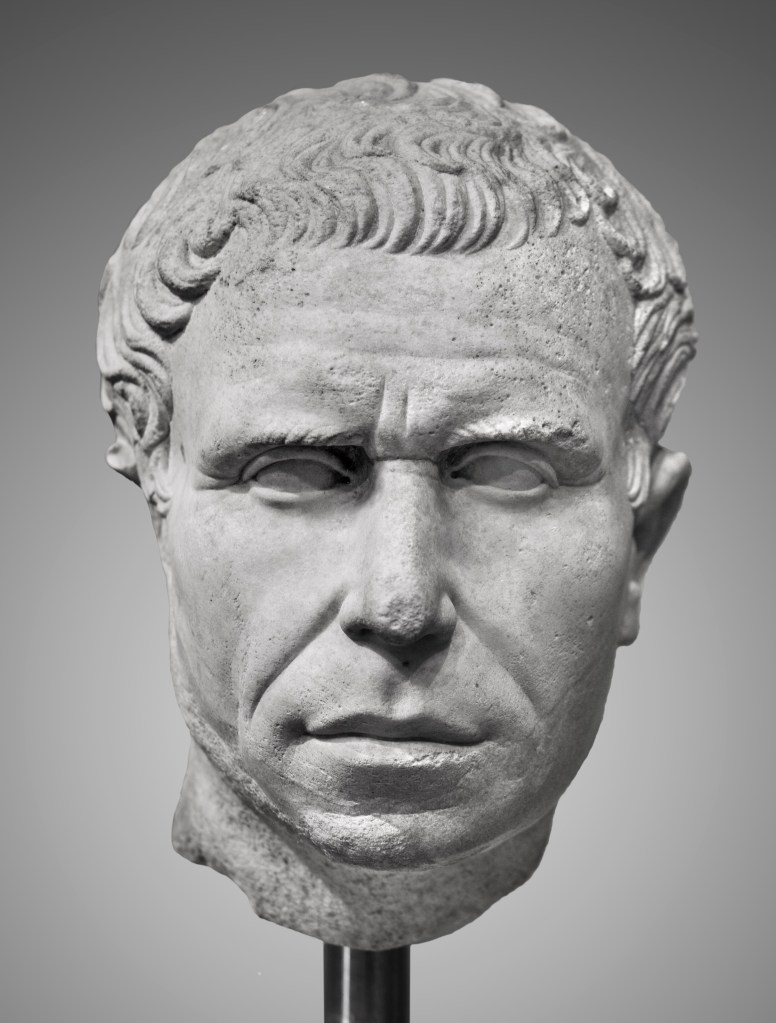

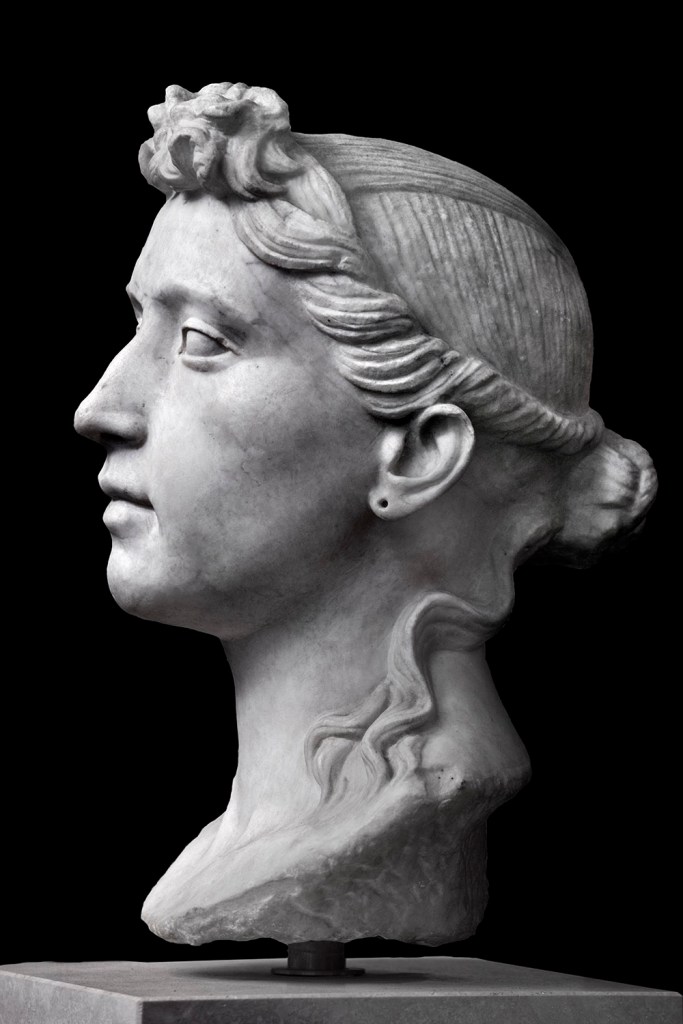

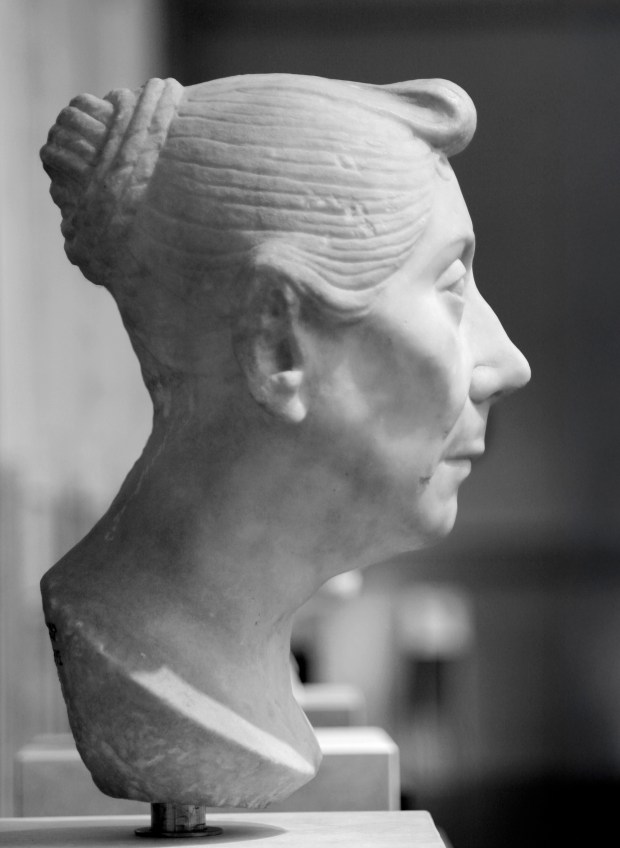

Republicans

The so-called General from Tivoli (Terme inv. 106513) was found beneath the Temple of Hercules in 1925. Dating to about 70 – 90 BC, he was probably a lieutenant of Sulla. The late-Republican portrait busts (Inv. 112301 and 114759) are famous for their verism – a style emphasizing unidealized realism. Rather than the smooth, youthful perfection of Greek sculpture, Roman patrons in this period wanted faces that looked weathered and unmistakably mortal. Eyes were often sharply undercut and hollowed to give depth and intensity. Cheeks could appear gaunt, lips thin and compressed, necks stringy. The overall effect was one of disciplined austerity and civic virtue – a face hardened by service to the Republic.

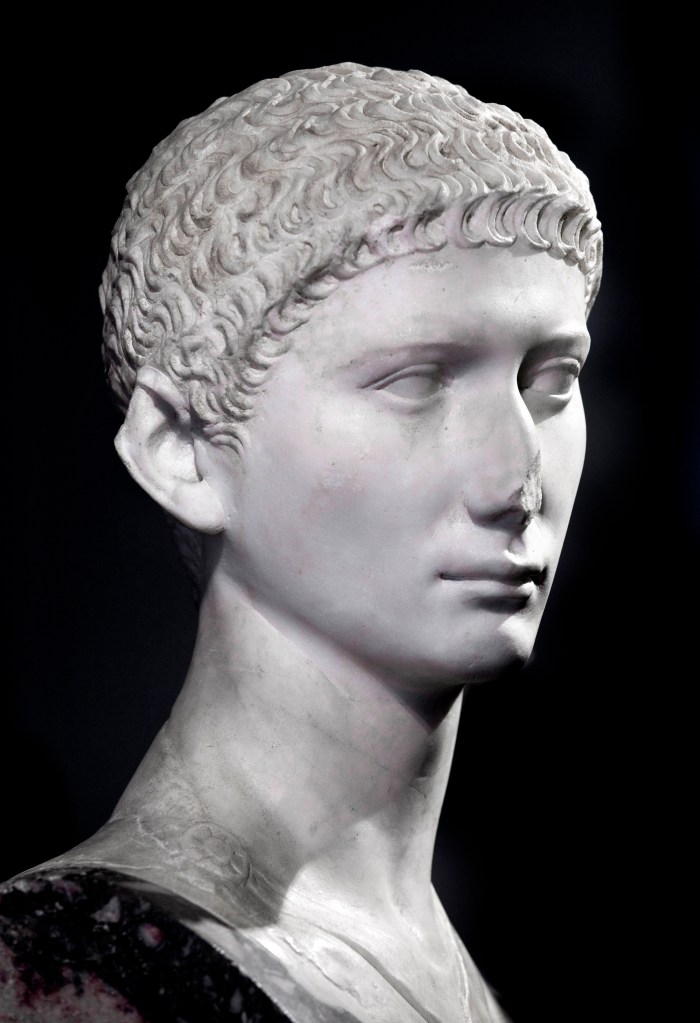

The young woman’s elaborate hairstyle (inv. 125591, just above) is a social signal, suggesting she belonged to a wealthy family or wanted to look the part. The combination of a classicizing ideal face with a detailed fashionable hairstyle suggests a woman who wants to present both grace and her social status. That blend of realism and idealization is typical of the late republic.

This was more selective exaggeration than realism. These men were advertising moral qualities: gravitas, virtus, fides. By the time of Caesar, you see a blending of this verism with a hint of idealization, anticipating the smooth, godlike Augustan portraits to come.

Speaking of late Republicans, this marble portrait of an elderly woman with her hair in a bun brings to mind another later Republican – Ronald Reagan.

The Sarcophagus of Marcus Claudianus

The continuous-frieze sarcophagus of Marcus Claudianus shows New Testament scenes on its front; and New and Old Testament scenes on its lid, along with pagan elements. The grape harvest imagery on the lid is ambiguous; it appears on pagan and Christian sarcophagi with identical elements. From left to right on the lid: Jesus nativity scene, sacrifice of Isaac, inscription naming the deceased, image of the deceased as scholar, grape harvest scene.

Carvings on the front of the sarcophagus: Arrest of Peter (Acts 12:3), miracle of water and wine (with possible baptism reference, John 2:1), orant figure, miracle of loaves (Mark 6:30–44, Matt 14:13–21, Luke 9:10–17, John 6:1–14), healing a man born blind (John 9:1), prediction of Peter’s denial (Mark 14:27–31, Matt 26:30–35, Luke 22:31–34, John 13:36–38), resurrection of Lazarus (John 11:1), and supplication of Lazarus’s sister (John 11:32).

The scenes on this sarcophagus include several apparent departures from scriptural miracle stories. Jesus appears in three places as magician, using a wand to perform miracles. He stands above five baskets of bread, a number consistent with most sarcophagi of its age but inconsistent with either of the loaves-and-fish scriptural pairs, where the remaining baskets number seven and twelve (Matthew 4:17, Matthew 15:34). This could have been a choice made by the sculptor for purely artistic reasons. The orant figure in the center is similar to those seen on earlier gravestones, and does not seem to be a scriptural reference. This posture is similar to that of the three youths in the furnace and the common sarcophagus scene of Jesus passing the new law to Peter and Paul (non-scriptural).

The Marcus Claudianus sarcophagus stands out for the prominence of Johannine-only imagery – Lazarus, the man born blind, Cana – scenes that are either uniquely Johannine or given distinct theological weight in that gospel. I don’t think you’ll hear this from anyone but me. I love this sarc for this reason. Compared to the sarcophagi from the Vatican necropolis, whose iconography often centers on synoptic or composite miracle cycles (feeding, healing, Jonah, Daniel, Good Shepherd), this sarc shows a notable shift toward Christological revelation rather than simple miracle narrative.

That shift says to me: mid-4th-century context, when Johannine motifs had become the backbone of Christian funerary theology. By that time, art was turning from generic symbols of deliverance to narratives that expressed Christ as Logos and life-giver, echoing themes prominent in the theological debates of the post-Nicene generation. The Lazarus scene, for example, takes on explicit resurrection connotations, and the healing of the blind man becomes an emblem of illumination through baptism – precisely the kind of allegorical reading developed in the decades after Constantine.

Earlier dating has been given by some scholars. Bunk. That impulse reflects anxiety over the scarcity of securely dated pre-Constantinian Christian monuments in Rome. Stylistically and iconographically, the Claudianus piece sits more naturally with sarcophagi of the 340s-360s: compressed compositions, monumental heads, frontal orant, and a selective, theological rather than narrative use of miracle scenes. And that’s probably more than you wanted to know about a topic I find fascinating because of what it says about modern Catholicism.

Bronze Athletes

The bronze athletes date from the Hellenistic period (second to first century BCE) convey the victory, exhaustion and fleeting nature of athletic glory.

The most famous of them, the Terme Boxer, was discovered on the Quirinal Hill in 1885. He sits slumped, body still powerful but spent, his face swollen and scarred, his hands wrapped in leather thongs. The artist cast every cut and bruise in bronze, even inlaid copper to suggest blood and wounds. Yet his expression is not defeat but endurance – a man who’s given everything to the arena.

Nearby, the Hellenistic Prince (or Terme Ruler), found in the same area, stands upright and nude, the counterpart to the seated boxer. His stance is heroic but weary, his gaze detached. Together the two figures tell both a moral story and a physical one: the the beauty and cost of strength.

These bronzes were likely imported to Rome as prized Greek originals or high-quality copies for a wealthy patron’s villa. They embody the Greek ideal of athletic excellence reframed through Roman admiration for the discipline and suffering behind it.

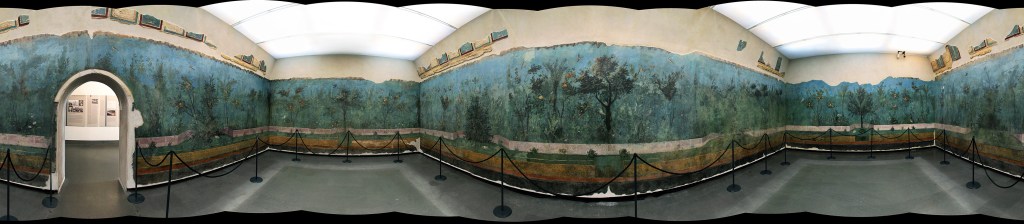

Wall Paintings/Frescoes

The villa wall paintings in Palazzo Massimo form one of the richest surviving narratives of Roman domestic life and taste. Most come from suburban villas around Rome, dating from the late Republic through the early Empire, and they recreate the visual world of elite Roman interiors.

The centerpiece is the set from Livia’s Villa at Prima Porta, discovered in 1863. The walls depict an illusionistic garden in full bloom – fruit trees, flowers, birds, and a soft blue sky.

Other rooms, such as those from the Villa of Farnesina, show mythological scenes, architectural vistas, and richly colored panels framed by columns and imaginary shrines. These follow the Second and Third Styles of Roman wall painting: first creating deep, theatrical perspective, then shifting to flatter, more decorative compositions filled with miniature landscapes and floating figures.

Taken together, the frescoes chart Rome’s transition from the austere republican taste for illusionistic space and Greek motifs to the sophisticated imperial language of myth, luxury, and controlled fantasy.

Cristo Docente

The Cristo Docente (Teaching Christ) clearly shows a youthful, androgynous body with small breasts. This is visual language flowing directly from Greco-Roman conventions of the philosopher, ephebe, or Apollo rather than an ethnographically accurate depiction of any historical Jesus. This one of the earliest depictions of Jesus, and a very rare example of Christian art not associated with burial. I wonder what the Vatican would trade for it.

Early Christian artists weren’t attempting realism; they were translating abstract theological ideas into iconic forms the viewer would recognize. The effeminate traits signal spiritual rather than biological qualities – gentleness, wisdom, eternal youth – while the frontal, often seated or teaching pose evokes authority and composure. In that cultural moment, a physically idealized, effeminate figure would convey the moral and divine authority expected of a teacher or savior without challenging Roman notions of masculinity, which were more flexible in the context of idealized youth and divinity.

The Christian anxiety that arises from this piece crack me up. Modern viewers, steeped in historical or doctrinal literalism, try to read the image literally. That’s a projection: the image is a theological construction, not an ethnographic one. Christian art critics, especially in the early 20th century, bristled at the iconography and tried to brush the thing off as a young girl posing as a scholar, rather than relaxing into the idea that early Christians weren’t like them.

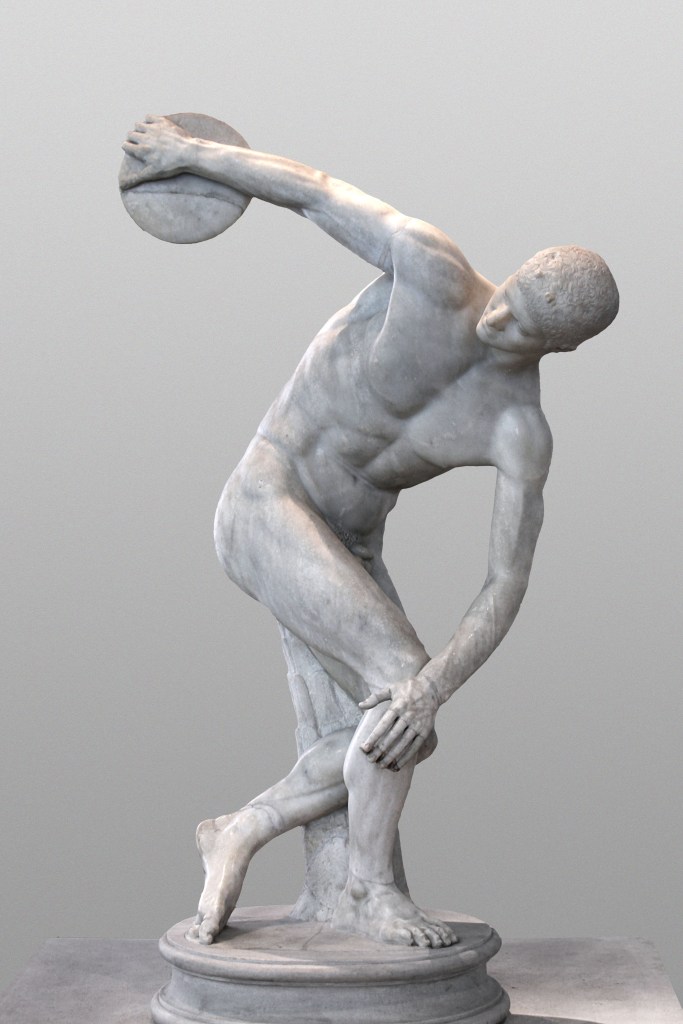

The Discobulus

This discobolus is interesting because it’s a Roman copy of a Greek original (traditionally attributed to Myron, mid-5th century BCE) but reinterpreted in a Roman context. Several points stand out:

Roman taste for idealized athleticism – Unlike the athletes that highlight strain and fatigue, the Discobolus captures frozen, perfect form in mid-action, emphasizing harmony, proportion, and controlled energy. The figure is taut, but serene, a demonstration of mastery over both body and motion.

Technical virtuosity – The sculpture compresses a dynamic twist of the torso and rotation of limbs into a balanced composition. The Massimo copy preserves this elegance while subtly softening the muscular definition compared with Hellenistic copies that exaggerate tension.

Cultural resonance in Rome – Displaying this statue in a Roman villa or public space signaled the moral and civic ideals associated with disciplined youth, athletic virtue, and controlled action—qualities the Roman elite wanted to project.

Roman copy as a lens on reception – we see how Romans interpreted Greek originals, choosing what to preserve, emphasize, or downplay. Unlike more dramatic Hellenistic works, this Discobolus shows restraint, aligning with Roman preferences for clarity, proportion, and intelligibility over theatricality. It’s a visual bridge between Greek athletic ideal and Roman moral-aesthetic ideology.

Bronze from Caligula’s Ships

The bronze fittings come from the two grand ceremonial vessels built in the lake of Lake Nemi, ordered by Gaius Caligula around AD 37-41. By commissioning such a floating palace, Caligula aligned himself with Hellenistic kings and with the mastery of nature. The bronzes speak that language of luxury and sacerdotal authority.

The vessels and their fittings were masterpieces of maritime technology, supported by massive beams, outriggers, twin rudders, and elaborate decoration. The bronze protomes were integrated in the structural and mechanical system of the ship (rudders, beams, mooring rings). Here is the transition from Republic to Imperial ornamentation in full flourish – Roman taste for Hellenistic luxury, combined with native iconography. The bronzes bridge functional object, architectural ornament, and political symbol.

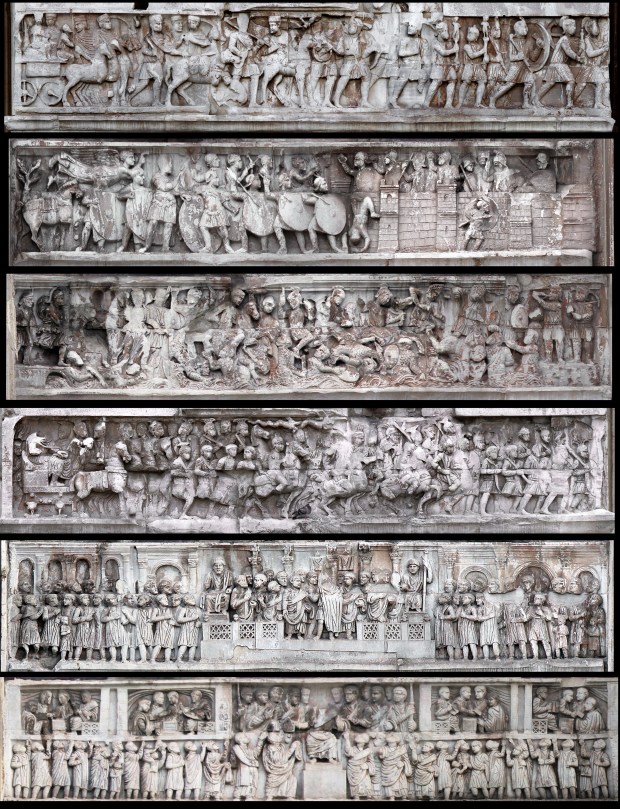

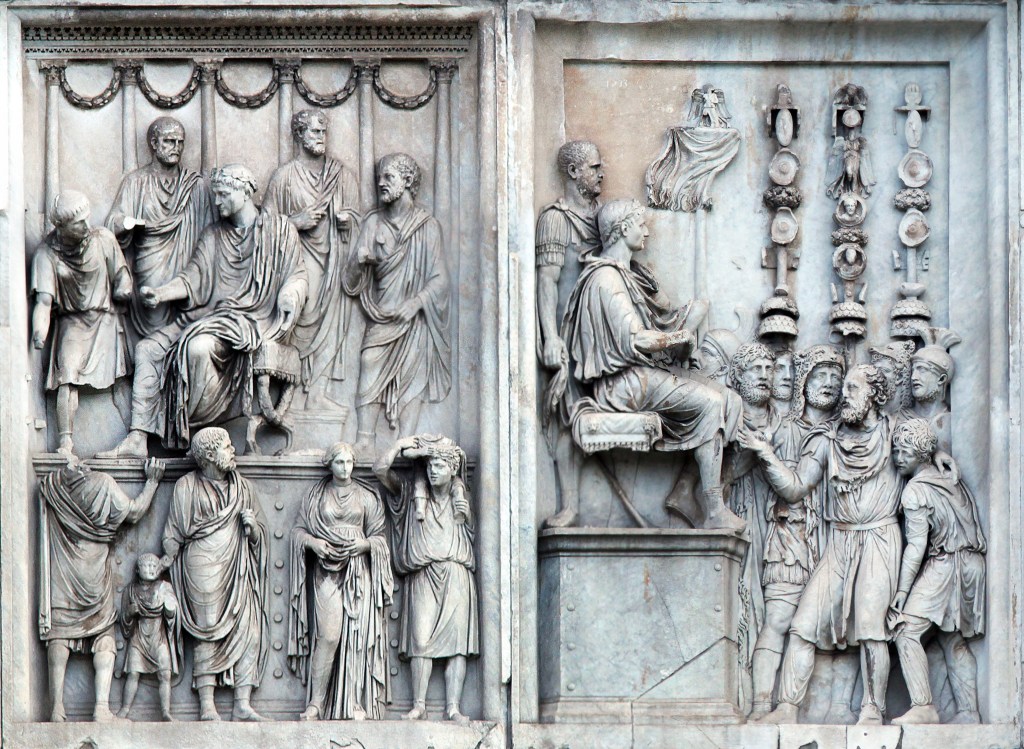

The Arch of Constantine

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Art on October 31, 2025

This is for Mike and Andrea, on their first visit to Rome.

Some people take up gardening. I dug into the Arch of Constantine. Deep. I’ll admit it, I got a little obsessed. What started as a quick look turned into a full dig through the dust of Roman politics as seen by art historians and classicists, writers with a gift for making the obvious sound profound and the profound impenetrable. Think of a collaboration between poets, lawyers, and a Latin thesaurus. One question led to another, and before I knew it, I was knee-deep in relief panels, inscriptions, and bitter academic feuds from 1903. If this teaser does anything for you, order a pizza and head over to my long version, revised today to incorporate recent scholarship, which is making great strides.

The Arch of Constantine stands just beside the Colosseum, massive and pale against the traffic. It was dedicated in 315 CE to celebrate Emperor Constantine’s victory over his rival Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge. On paper it’s a “triumphal arch,” but that’s not quite true. Constantine never held a formal triumph, and the monument itself was assembled partly from spare parts of older imperial projects.

Most of what you see wasn’t made for Constantine at all. His builders raided earlier monuments – especially from the reigns of Hadrian, Trajan, and Marcus Aurelius – and grafted those sculptures onto the new structure. Look closely and you can still spot the mismatches. The heads have been recut. A scene that once showed Emperor Hadrian hunting a lion now shows Constantine doing the honors, with a few clumsy adjustments to the drapery. Other panels, taken from Marcus Aurelius’s monuments, show the emperor addressing troops or granting clemency, only now it’s Constantine’s face and Constantine’s name.

These borrowed panels aren’t just decoration. They were carefully chosen to tie Constantine to the “good emperors” of the past, especially Marcus Aurelius, the philosopher-king. By mixing their images with his own, Constantine claimed continuity with Rome’s golden age while quietly erasing the messy years between.

The long strip of carving that wraps around the lower part of the arch is the one section made entirely for Constantine’s time. It’s a running narrative of his civil war against Maxentius. Starting on the west side, you can see Constantine setting out from Milan, soldiers marching behind his chariot. Around the corner, he besieges a walled city – probably Verona – and towers over his men, twice their size, a new kind of emperor who commands by sheer presence. The next panel shows the chaotic battle at the Milvian Bridge, where Maxentius’s troops drown in the Tiber while Constantine’s army presses forward. The story ends with Constantine entering Rome and addressing the citizens from a raised platform, a ruler both human and divine.

The figures look stiff and simplified compared to the older reliefs above them, but that’s part of the shift the arch represents. Art was moving away from naturalism toward symbolism. Constantine isn’t shown as an individual man but as an idea: the chosen ruler, the earthly image of divine authority.

That message runs through the inscription carved across the top. It declares that Constantine won instinctu divinitatis – “by divine inspiration.” The phrase is unique; no one had used it before. It’s deliberately vague, as if leaving room for different gods to take the credit. For pagans, it could mean Apollo or Sol Invictus. For Christians, it sounded like the hand of the one God. Either way, it announced a new kind of emperor, one who ruled not just with the favor of the gods but through them.

The Arch of Constantine isn’t simply a monument to a battle. It’s a scrapbook of Rome’s artistic past and a statement of political legitimacy. Read carefully, it is an early sign that the empire was in for religion, hard times, and down-sizing.

Photos and text copyright 2025 by William K Storage

From Aqueducts to Algorithms: The Cost of Consensus

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science on July 9, 2025

The Scientific Revolution, we’re taught, began in the 17th century – a European eruption of testable theories, mathematical modeling, and empirical inquiry from Copernicus to Newton. Newton was the first scientist, or rather, the last magician, many historians say. That period undeniably transformed our understanding of nature.

Historians increasingly question whether a discrete “scientific revolution” ever happened. Floris Cohen called the label a straightjacket. It’s too simplistic to explain why modern science, defined as the pursuit of predictive, testable knowledge by way of theory and observation, emerged when and where it did. The search for “why then?” leads to Protestantism, capitalism, printing, discovered Greek texts, scholasticism, even weather. That’s mostly just post hoc theorizing.

Still, science clearly gained unprecedented momentum in early modern Europe. Why there? Why then? Good questions, but what I wonder, is why not earlier – even much earlier.

Europe had intellectual fireworks throughout the medieval period. In 1320, Jean Buridan nearly articulated inertia. His anticipation of Newton is uncanny, three centuries earlier:

“When a mover sets a body in motion he implants into it a certain impetus, that is, a certain force enabling a body to move in the direction in which the mover starts it, be it upwards, downwards, sidewards, or in a circle. The implanted impetus increases in the same ratio as the velocity. It is because of this impetus that a stone moves on after the thrower has ceased moving it. But because of the resistance of the air (and also because of the gravity of the stone) … the impetus will weaken all the time. Therefore the motion of the stone will be gradually slower, and finally the impetus is so diminished or destroyed that the gravity of the stone prevails and moves the stone towards its natural place.”

Robert Grosseteste, in 1220, proposed the experiment-theory iteration loop. In his commentary on Aristotle’s Posterior Analytics, he describes what he calls “resolution and composition”, a method of reasoning that moves from particulars to universals, then from universals back to particulars to make predictions. Crucially, he emphasizes that both phases require experimental verification.

In 1360, Nicole Oresme gave explicit medieval support for a rotating Earth:

“One cannot by any experience whatsoever demonstrate that the heavens … are moved with a diurnal motion… One can not see that truly it is the sky that is moving, since all movement is relative.”

He went on to say that the air moves with the Earth, so no wind results. He challenged astrologers:

“The heavens do not act on the intellect or will… which are superior to corporeal things and not subject to them.”

Even if one granted some influence of the stars on matter, Oresme wrote, their effects would be drowned out by terrestrial causes.

These were dead ends, it seems. Some blame the Black Death, but the plague left surprisingly few marks in the intellectual record. Despite mass mortality, history shows politics, war, and religion marching on. What waned was interest in reviving ancient learning. The cultural machinery required to keep the momentum going stalled. Critical, collaborative, self-correcting inquiry didn’t catch on.

A similar “almost” occurred in the Islamic world between the 10th and 16th centuries. Ali al-Qushji and al-Birjandi developed sophisticated models of planetary motion and even toyed with Earth’s rotation. A layperson would struggle to distinguish some of al-Birjandi’s thought experiments from Galileo’s. But despite a wealth of brilliant scholars, there were few institutions equipped or allowed to convert knowledge into power. The idea that observation could disprove theory or override inherited wisdom was socially and theologically unacceptable. That brings us to a less obvious candidate – ancient Rome.

Rome is famous for infrastructure – aqueducts, cranes, roads, concrete, and central heating – but not scientific theory. The usual story is that Roman thought was too practical, too hierarchical, uninterested in pure understanding.

One text complicates that story: De Architectura, a ten-volume treatise by Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, written during the reign of Augustus. Often described as a manual for builders, De Architectura is far more than a how-to. It is a theoretical framework for knowledge, part engineering handbook, part philosophy of science.

Vitruvius was no scientist, but his ideas come astonishingly close to the scientific method. He describes devices like the Archimedean screw or the aeolipile, a primitive steam engine. He discusses acoustics in theater design, and a cosmological models passed down from the Greeks. He seems to describe vanishing point perspective, something seen in some Roman art of his day. Most importantly, he insists on a synthesis of theory, mathematics, and practice as the foundation of engineering. His describes something remarkably similar to what we now call science:

“The engineer should be equipped with knowledge of many branches of study and varied kinds of learning… This knowledge is the child of practice and theory. Practice is the continuous and regular exercise of employment… according to the design of a drawing. Theory, on the other hand, is the ability to demonstrate and explain the productions of dexterity on the principles of proportion…”

“Engineers who have aimed at acquiring manual skill without scholarship have never been able to reach a position of authority… while those who relied only upon theories and scholarship were obviously hunting the shadow, not the substance. But those who have a thorough knowledge of both… have the sooner attained their object and carried authority with them.”

This is more than just a plea for well-rounded education. H e gives a blueprint for a systematic, testable, collaborative knowledge-making enterprise. If Vitruvius and his peers glimpsed the scientific method, why didn’t Rome take the next step?

The intellectual capacity was clearly there. And Roman engineers, like their later European successors, had real technological success. The problem, it seems, was societal receptiveness.

Science, as Thomas Kuhn famously brough to our attention, is a social institution. It requires the belief that man-made knowledge can displace received wisdom. It depends on openness to revision, structured dissent, and collaborative verification. These were values that the Roman elite culture distrusted.

When Vitruvius was writing, Rome had just emerged from a century of brutal civil war. The Senate and Augustus were engaged in consolidating power, not questioning assumptions. Innovation, especially social innovation, was feared. In a political culture that prized stability, hierarchy, and tradition, the idea that empirical discovery could drive change likely felt dangerous.

We see this in Cicero’s conservative rhetoric, in Seneca’s moralism, and in the correspondence between Pliny and Trajan, where even mild experimentation could be viewed as subversive. The Romans could build aqueducts, but they wouldn’t fund a lab.

Like the Islamic world centuries later, Rome had scholars but not systems. Knowledge existed, but the scaffolding to turn it into science – collective inquiry, reproducibility, peer review, invitations for skeptics to refute – never emerged.

Vitruvius’s De Architectura deserves more attention, not just as a technical manual but as a proto-scientific document. It suggests that the core ideas behind science were not exclusive to early modern Europe. They’ve flickered into existence before, in Alexandria, Baghdad, Paris, and Rome, only to be extinguished by lack of institutional fit.

That science finally took root in the 17th century had less to do with discovery than with a shift in what society was willing to do with discovery. The real revolution wasn’t in Newton’s laboratory, it was in the culture.

Rome’s Modern Echo?

It’s worth asking whether we’re becoming more Roman ourselves. Today, we have massively resourced research institutions, global scientific networks, and generations of accumulated knowledge. Yet, in some domains, science feels oddly stagnant or brittle. Dissenting views are not always engaged but dismissed, not for lack of evidence, but for failing to fit a prevailing narrative.

We face a serious, maybe existential question. Does increasing ideological conformity, especially in academia, foster or hamper science?

Obviously, some level of consensus is essential. Without shared standards, peer review collapses. Climate models, particle accelerators, and epidemiological studies rely on a staggering degree of cooperation and shared assumptions. Consensus can be a hard-won product of good science. And it can run perilously close to dogma. In the past twenty years we’ve seen consensus increasingly enforced by legal action, funding monopolies, and institutional ostracism.

String theory may (or may not) be physics’ great white whale. It’s mathematically exquisite but empirically elusive. For decades, critics like Lee Smolin and Peter Woit have argued that string theory has enjoyed a monopoly on prestige and funding while producing little testable output. Dissenters are often marginalized.

Climate science is solidly evidence-based, but responsible scientists point to constant revision of old evidence. Critics like Judith Curry or Roger Pielke Jr. have raised methodological or interpretive concerns, only to find themselves publicly attacked or professionally sidelined. Their critique is labeled denial. Scientific American called Curry a heretic. Lawsuits, like Michael Mann’s long battle with critics, further signal a shift from scientific to pre-scientific modes of settling disagreement.

Jonathan Haidt, Lee Jussim, and others have documented the sharp political skew of academia, particularly in the humanities and social sciences, but increasingly in hard sciences too. When certain political assumptions are so embedded, they become invisible. Dissent is called heresy in an academic monoculture. This constrains the range of questions scientists are willing to ask, a problem that affects both research and teaching. If the only people allowed to judge your work must first agree with your premises, then peer review becomes a mechanism of consensus enforcement, not knowledge validation.

When Paul Feyerabend argued that “the separation of science and state” might be as important as the separation of church and state, he was pushing back against conservative technocratic arrogance. Ironically, his call for epistemic anarchism now resonates more with critics on the right than the left. Feyerabend warned that uniformity in science, enforced by centralized control, stifles creativity and detaches science from democratic oversight.

Today, science and the state, including state-adjacent institutions like universities, are deeply entangled. Funding decisions, hiring, and even allowable questions are influenced by ideology. This alignment with prevailing norms creates a kind of soft theocracy of expert opinion.

The process by which scientific knowledge is validated must be protected from both politicization and monopolization, whether that comes from the state, the market, or a cultural elite.

Science is only self-correcting if its institutions are structured to allow correction. That means tolerating dissent, funding competing views, and resisting the urge to litigate rather than debate. If Vitruvius teaches us anything, it’s that knowing how science works is not enough. Rome had theory, math, and experimentation. What it lacked was a social system that could tolerate what those tools would eventually uncover. We do not yet lack that system, but we are testing the limits.

After the Applause: Heilbron Rereads Feyerabend

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science, Philosophy of Science on June 4, 2025

A decade ago, in a Science, Technology and Society (STS) roundtable, I brought up Paul Feyerabend, who was certainly familiar to everyone present. I said that his demand for a separation of science and state – his call to keep science from becoming a tool of political authority – seemed newly relevant in the age of climate science and policy entanglement. Before I could finish the thought, someone cut in: “You can’t use Feyerabend to support republicanism!”

I hadn’t made an argument. Feyerabend was being claimed as someone who belonged to one side of a cultural war. His ideas were secondary. That moment stuck with me, not because I was misunderstood, but because Feyerabend was. And maybe he would have loved that. He was ambiguous by design. The trouble is that his deliberate opacity has hardened, over time, into distortion.

Feyerabend survives in fragments and footnotes. He’s the folk hero who overturned Method and danced on its ruins. He’s a cautionary tale: the man who gave license to science denial, epistemic relativism, and rhetorical chaos. You’ll find him invoked in cultural studies and critiques of scientific rationality, often with little more than the phrase “anything goes” as evidence. He’s also been called “the worst enemy of science.”

Against Method is remembered – or reviled – as a manifesto for intellectual anarchy. But “manifesto” doesn’t fit at all. It didn’t offer a vision, a list of principles, or a path forward. It has no normative component. It offered something stranger: a performance.

Feyerabend warned readers in the preface that the book would contradict itself, that it wasn’t impartial, and that it was meant to persuade, not instruct. He said – plainly and explicitly – that later parts would refute earlier ones. It was, in his words, a “tendentious” argument. And yet neither its admirers nor its critics have taken that warning seriously.

Against Method has become a kind of Rorschach test. For some, it’s license; for others, sabotage. Few ask what Feyerabend was really doing – or why he chose that method to attack Method. A few of us have long argued that Against Method has been misread. It was never meant as a guidebook or a threat, but as a theatrical critique staged to provoke and destabilize something that badly needed destabilizing.

That, I was pleased to learn, is also the argument made quietly and precisely in the last published work of historian John Heilbron. It may be the most honest reading of Feyerabend we’ve ever had.

John once told me that, unlike Kuhn, he had “the metabolism of a historian,” a phrase that struck me later as a perfect self-diagnosis: patient, skeptical, and slow-burning. He’d been at Berkeley when Feyerabend was still strutting the halls in full flair – the accent, the dramatic pronouncements, the partying. John didn’t much like him. He said so over lunch, on walks, at his house or mine. Feyerabend was hungry for applause, and John disapproved of his personal appetites and the way he flaunted them.

And yet… John’s recent piece on Feyerabend – the last thing he ever published – is microscopically delicate, charitable, and clear-eyed. John’s final chapter in Stefano Gattei’s recent book, Feyerabend in Dialogue, contains no score-settling, no demolition. Just a forensic mind trained to separate signal from noise. If Against Method is a performance, Heilbron doesn’t boo it offstage. He watches it again, closely, and tells us how it was done. Feyerabend through Heilbron’s lens is a performance reframed.

If anyone was positioned to make sense of Feyerabend, rhetorically, philosophically, and historically, it was Heilbron – Thomas Kuhn’s first graduate student, a lifelong physicist-turned-historian, and an expert on both early modern science and quantum theory’s conceptual tangles. His work on Galileo, Bohr, and the Scientific Revolution was always precise, occasionally sly, and never impressed by performance for performance’s sake.

That care is clearest in his treatment of Against Method’s most famous figure: Galileo. Feyerabend made Galileo the centerpiece of his case against scientific method – not as a heroic rationalist, but as a cunning rhetorician who won not because of superior evidence, but because of superior style. He compared Galileo to Goebbels, provocatively, to underscore how persuasion, not demonstration, drove the acceptance of heliocentrism. In Feyerabend’s hands, Galileo became a theatrical figure, a counterweight to the myth of Enlightenment rationality.

Heilbron dismantles this with the precision of someone who has lived in Galileo’s archives. He shows that while Galileo lacked a modern theory of optics, he was not blind to his telescope’s limits. He cross-checked, tested, and refined. He triangulated with terrestrial experiments. He understood that instruments could deceive, and worked around that risk with repetition and caution. The image of Galileo as a showman peddling illusions doesn’t hold up. Galileo, flaws acknowledged, was a working proto-scientist, attentive to the fragility of his tools.

Heilbron doesn’t mythologize Galileo; his 2010 Galileo makes that clear. But he rescues Galileo from Feyerabend’s caricature. In doing so, he models something Against Method never offered: a historically grounded, philosophically rigorous account of how science proceeds when tools are new, ideas unstable, and theory underdetermined by data.

To be clear, Galileo was no model of transparency. He framed the Dialogue as a contest between Copernicus and Ptolemy, though he knew Tycho Brahe’s hybrid system was the more serious rival. He pushed his theory of tides past what his evidence could support, ignoring counterarguments – even from Cardinal Bellarmine – and overstating the case for Earth’s motion.

Heilbron doesn’t conceal these. He details them, but not to dismiss. For him, these distortions are strategic flourishes – acts of navigation by someone operating at the edge of available proof. They’re rhetorical, yes, but grounded in observation, subject to revision, and paid for in methodological care.

That’s where the contrast with Feyerabend sharpens. Feyerabend used Galileo not to advance science, but to challenge its authority. More precisely, to challenge Method as the defining feature of science. His distortions – minimizing Galileo’s caution, questioning the telescope, reimagining inquiry as theater – were made not in pursuit of understanding, but in service of a larger philosophical provocation. This is the line Heilbron quietly draws: Galileo bent the rules to make a case about nature; Feyerabend bent the past to make a case about method.

In his final article, Heilbron makes four points. First, that the Galileo material in Against Method – its argumentative keystone – is historically slippery and intellectually inaccurate. Feyerabend downplays empirical discipline and treats rhetorical flourish as deception. Heilbron doesn’t call this dishonest. He calls it stagecraft.

Second, that Feyerabend’s grasp of classical mechanics, optics, and early astronomy was patchy. His critique of Galileo’s telescope rests on anachronistic assumptions about what Galileo “should have” known. He misses the trial-based, improvisational reasoning of early instrumental science. Heilbron restores that context.

Third, Heilbron credits Feyerabend’s early engagement with quantum mechanics – especially his critique of von Neumann’s no-hidden-variables proof and his alignment with David Bohm’s deterministic alternative. Feyerabend’s philosophical instincts were sharp.

And fourth, Heilbron tracks how Feyerabend’s stance unraveled – oscillating between admiration and disdain for Popper, Bohr, and even his earlier selves. He supported Bohm against Bohr in the 1950s, then defended Bohr against Popper in the 1970s. Heilbron doesn’t call this hypocrisy. He calls it instability built into the project itself: Feyerabend didn’t just critique rationalism – he acted out its undoing. If this sounds like a takedown, it isn’t. It’s a reconstruction – calm, slow, impartial. The rare sort that shows us not just what Feyerabend said, but where he came apart.

Heilbron reminds us what some have forgotten and many more never knew: that Feyerabend was once an insider. Before Against Method, he was embedded in the conceptual heart of quantum theory. He studied Bohm’s challenge to Copenhagen while at LSE, helped organize the 1957 Colston symposium in Bristol, and presented a paper there on quantum measurement theory. He stood among physicists of consequence – Bohr, Bohm, Podolsky, Rosen, Dirac, and Pauli – all struggling to articulate alternatives to an orthodoxy – Copenhagen Interpretation – that they found inadequate.

With typical wit, Heilbron notes that von Neumann’s no-hidden-variables proof “was widely believed, even by people who had read it.” Feyerabend saw that dogma was hiding inside the math – and tried to smoke it out.

Late in life, Feyerabend’s provocations would ripple outward in unexpected directions. In a 1990 lecture at Sapienza University, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger – later Pope Benedict XVI – quoted Against Method approvingly. He cited Feyerabend’s claim that the Church had been more reasonable than Galileo in the affair that defined their rupture. When Ratzinger’s 2008 return visit was canceled due to protests about that quotation, the irony was hard to miss. The Church, once accused of silencing science, was being silenced by it, and stood accused of quoting a philosopher who spent his life telling scientists to stop pretending they were priests.

We misunderstood Feyerabend not because he misled us, but because we failed to listen the way Heilbron did.

Anarchy and Its Discontents: Paul Feyerabend’s Critics

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science, Philosophy of Science on June 3, 2025

(For and against Against Method)

Paul Feyerabend’s 1975 Against Method and his related works made bold claims about the history of science, particularly the Galileo affair. He argued that science progressed not because of adherence to any specific method, but through what he called epistemological anarchism. He said that Galileo’s success was due in part to rhetoric, metaphor, and politics, not just evidence.

Some critics, especially physicists and historically rigorous philosophers of science, have pointed out technical and historical inaccuracies in Feyerabend’s treatment of physics. Here are some examples of the alleged errors and distortions:

Misunderstanding Inertial Frames in Galileo’s Defense of Copernicanism

Feyerabend argued that Galileo’s arguments for heliocentrism were not based on superior empirical evidence, and that Galileo used rhetorical tricks to win support. He claimed that Galileo simply lacked any means of distinguishing heliocentric from geocentric models empirically, so his arguments were no more rational than those of Tycho Brahe and other opponents.

His critics responded by saying that Galileo’s arguments based on the phases of Venus and Jupiter’s moons were empirically decisive against the Ptolemaic model. This is unarguable, though whether Galileo had empirical evidence to overthrow Tycho Brahe’s hybrid model is a much more nuanced matter.

Critics like Ronald Giere, John Worrall, and Alan Chalmers (What Is This Thing Called Science?) argued that Feyerabend underplayed how strong Galileo’s observational case actually was. They say Feyerabend confused the issue of whether Galileo had a conclusive argument with whether he had a better argument.

This warrants some unpacking. Specifically, what makes an argument – a model, a theory – better? Criteria might include:

- Empirical adequacy – Does the theory fit the data? (Bas van Fraassen)

- Simplicity – Does the theory avoid unnecessary complexity? (Carl Hempel)

- Coherence – Is it internally consistent? (Paul Thagard)

- Explanatory power – Does it explain more than rival theories? (Wesley Salmon)

- Predictive power – Does it generate testable predictions? (Karl Popper, Hempel)

- Fertility – Does it open new lines of research? (Lakatos)

Some argue that Galileo’s model (Copernicanism, heliocentrism) was obviously simpler than Brahe’s. But simplicity opens another can of philosophical worms. What counts as simple? Fewer entities? Fewer laws? More symmetry? Copernicus had simpler planetary order but required a moving Earth. And Copernicus still relied on epicycles, so heliocentrism wasn’t empirically simpler at first. Given the evidence of the time, a static Earth can be seen as simpler; you don’t need to explain the lack of wind and the “straight” path of falling bodies. Ultimately, this point boils down to aesthetics, not math or science. Galileo and later Newtonians valued mathematical elegance and unification. Aristotelians, the church, and Tychonians valued intuitive compatibility with observed motion.

Feyerabend also downplayed Galileo’s use of the principle of inertia, which was a major theoretical advance and central to explaining why we don’t feel the Earth’s motion.

Misuse of Optical Theory in the Case of Galileo’s Telescope

Feyerabend argued that Galileo’s use of the telescope was suspect because Galileo had no good optical theory and thus no firm epistemic ground for trusting what he saw.

His critics say that while Galileo didn’t have a fully developed geometrical optics theory (e.g., no wave theory of light), his empirical testing and calibration of the telescope were rigorous by the standards of the time.

Feyerabend is accused of anachronism – judging Galileo’s knowledge of optics by modern standards and therefore misrepresenting the robustness of his observational claims. Historians like Mario Biagioli and Stillman Drake point out that Galileo cross-verified telescope observations with the naked eye and used repetition, triangulation, and replication by others to build credibility.

Equating All Theories as Rhetorical Equals

Feyerabend in some parts of Against Method claimed that rival theories in the history of science were only judged superior in retrospect, and that even “inferior” theories like astrology or Aristotelian cosmology had equal rational footing at the time.

Historians like Steven Shapin (How to be Antiscientific) and David Wootton (The Invention of Science) say that this relativism erases real differences in how theories were judged even in Galileo’s time. While not elaborated in today’s language, Galileo and his rivals clearly saw predictive power, coherence, and observational support as fundamental criteria for choosing between theories.

Feyerabend’s polemical, theatrical tone often flattened the epistemic distinctions that working scientists and philosophers actually used, especially during the Scientific Revolution. His analysis of “anything goes” often ignored the actual disciplinary practices of science, especially in physics.

Failure to Grasp the Mathematical Structure of Physics

Scientists – those broad enough to know who Feyerabend was – often claim that he misunderstood or ignored the role of mathematics in theory-building, especially in Newtonian mechanics and post-Galilean developments. In Against Method, Feyerabend emphasizes metaphor and persuasion over mathematics. While this critique is valuable when aimed at the rhetorical and political sides of science, it underrates the internal mathematical constraints that shape physical theories, even for Galileo.

Imre Lakatos, his friend and critic, called Feyerabend’s work a form of “intellectual sabotage”, arguing that he distorted both the history and logic of physics.

Misrepresenting Quantum Mechanics

Feyerabend wrote about Bohr and Heisenberg in Philosophical Papers and later essays. Critics like Abner Shimony and Mario Bunge charge that Feyerabend misrepresented or misunderstood Bohr’s complementarity as relativistic, when Bohr’s position was more subtle and aimed at objective constraints on language and measurement.

Feyerabend certainly fails to understand the mathematical formalism underpinning Quantum Mechanics. This weakens his broader claims about theory incommensurability.

Feyerabend’s erroneous critique of Neil’s Bohr is seen in his 1958 Complimentarity:

“Bohr’s point of view may be introduced by saying that it is the exact opposite of [realism]. For Bohr the dual aspect of light and matter is not the deplorable consequence of the absence of a satisfactory theory, but a fundamental feature of the microscopic level. For him the existence of this feature indicates that we have to revise … the [realist] ideal of explanation.” (more on this in an upcoming post)

Epistemic Complaints

Beyond criticisms that he failed to grasp the relevant math and science, Feyerabend is accused of selectively reading or distorting historical episodes to fit the broader rhetorical point that science advances by breaking rules, and that no consistent method governs progress. Feyerabend’s claim that in science “anything goes” can be seen as epistemic relativism, leaving no rational basis to prefer one theory over another or to prefer science over astrology, myth, or pseudoscience.

Critics say Feyerabend blurred the distinction between how theories are argued (rhetoric) and how they are justified (epistemology). He is accused of conflating persuasive strategy with epistemic strength, thereby undermining the very principle of rational theory choice.

Some take this criticism to imply that methodological norms are the sole basis for theory choice. Feyerabend’s “anarchism” may demolish authority, but is anything left in its place except a vague appeal to democratic or cultural pluralism? Norman Levitt and Paul Gross, especially in Higher Superstition: The Academic Left and Its Quarrels with Science (1994), argue this point, along with saying Feyerabend attacked a caricature of science.

Personal note/commentary: In my view, Levitt and Gross did some great work, but Higher Superstition isn’t it. I bought the book shortly after its release because I was disgusted with weaponized academic anti-rationalism, postmodernism, relativism, and anti-science tendencies in the humanities, especially those that claimed to be scientific. I was sympathetic to Higher Superstition’s mission but, on reading it, was put off by its oversimplifications and lack of philosophical depth. Their arguments weren’t much better than those of the postmodernists. Critics of science in the humanities critics overreached and argued poorly, but they were responding to legitimate concerns in the philosophy of science. Specifically:

- Underdetermination – Two incompatible theories often fit the same data. Why do scientists prefer one over another? As Kuhn argued, social dynamics play a role.

- Theory-laden Observations – Observations are shaped by prior theory and assumptions, so science is not just “reading the book of nature.”

- Value-laden Theories – Public health metrics like life expectancy and morbidity (opposed to autonomy or quality of life) trickle into epidemiology.

- Historical Variability of Consensus – What’s considered rational or obvious changes over time (phlogiston, luminiferous ether, miasma theory).

- Institutional Interest and Incentives – String theory’s share of limited research funding, climate science in service of energy policy and social agenda.

- The Problem of Reification – IQ as a measure of intelligence has been reified in policy and education, despite deep theoretical and methodological debates about what it measures.

- Political or Ideological Capture – Marxist-Leninist science and eugenics were cases where ideology shaped what counted as science.

Higher Superstition and my unexpected negative reaction to it are what brought me to the discipline of History and Philosophy of Science.

Conclusion

Feyerabend exaggerated the uncertainty of early modern science, downplayed the empirical gains Galileo and others made, and misrepresented or misunderstood some of the technical content of physics. His mischievous rhetorical style made it hard to tell where serious argument ended and performance began. Rather than offering a coherent alternative methodology, Feyerabend’s value lay in exposing the fragility and contingency of scientific norms. He made it harder to treat methodological rules as timeless or universal by showing how easily they fracture under the pressure of real historical cases.

In a following post, I’ll review the last piece John Heilbron wrote before he died, Feyerabend, Bohr and Quantum Physics, which appeared in Stefano Gattei’s Feyerabend in Dialogue, a set of essays marking the 100th anniversary of Feyerabend’s birth.

Paul Feyerabend. Photo courtesy of Grazia Borrini-Feyerabend.

John Heilbron Interview – June 2012

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science, Philosophy of Science on June 2, 2025

In 2012, I spoke with John Heilbron, historian of science and Professor Emeritus at UC Berkeley, about his career, his work with Thomas Kuhn, and the legacy of The Structure of Scientific Revolutions on its 50th anniversary. We talked late into the night. The conversation covered his shift from physics to history, his encounters with Kuhn and Paul Feyerabend, and his critical take on the direction of Science and Technology Studies (STS).

The interview marked a key moment. Kuhn and Feyerabend’s legacies were under fresh scrutiny, and STS was in the midst of redefining itself, often leaning toward sociological frameworks at the expense of other approaches.

Thirteen years later, in 2025, this commentary revisits that interview to illuminate its historical context, situate Heilbron’s critiques, and explore their relevance to contemporary STS and broader academic debates.

Over more than a decade, I had ongoing conversations with Heilbron about the evolution of the history of science – history of the history of science – and the complex relationship between History of Science and Science, Technology, and Society (STS) programs. At UC Berkeley, unlike at Harvard or Stanford, STS has long remained a “Designated Emphasis” rather than a department or standalone degree. Academic conservatism in departmental structuring, concerns about reputational risk, and questions about the epistemic rigor of STS may all have contributed to this decision. Moreover, Berkeley already boasted world-class departments in both History and Sociology.

That 2012 interview, the only one we recorded, brought together themes we’d explored over many years. Since then, STS has moved closer to engaging with scientific content itself. But it still draws criticism, both from scientists and from public misunderstanding. In 2012, the field was still heavily influenced by sociological models, particularly the Strong Programme and social constructivism, which stressed how scientific knowledge is shaped by social context. One of the key texts in this tradition, Shapin and Schaffer’s Leviathan and the Air-Pump (1985), argued that even Boyle’s experiments weren’t simply about discovery but about constructing scientific consensus.

Heilbron pushed back against this framing. He believed it sidelined the technical and epistemic depth of science, reducing STS to a sociological critique. He was especially wary of the dense, abstract language common in constructivist work. In his view, it often served as cover for thin arguments, especially from younger scholars who copied the style but not the substance. He saw it as a tactic: establish control of the conversation by embedding a set of terms, then build influence from there.

The influence of Shapin and Schaffer, Heilbron argued, created the impression that STS was dominated by a single paradigm, ironically echoing the very Kuhnian framework they analyzed. His frustration with a then-recent Isis review reflected his concern that constructivism had become doctrinaire, pressuring scholars to conform to its methods even when irrelevant to their work. His reference to “political astuteness” pointed to the way in which key figures in the field successfully advanced their terminology and frameworks, gaining disproportionate influence. While this gave them intellectual clout, Heilbron saw it as a double-edged sword: it strengthened their position while encouraging dogmatism among followers who prioritized jargon over genuine analysis.

Bill Storage: How did you get started in this curious interdisciplinary academic realm?

John Heilbron: Well, it’s not really very interesting, but I was a graduate student in physics but my real interest was history. So at some point I went down to the History department and found the medievalist, because I wanted to do medieval history. I spoke with the medievalist ad he said, “well, that’s very charming but you know the country needs physicists and it doesn’t need medievalists, so why don’t you go back to physics.” Which I duly did. But he didn’t bother to point out that there was this guy Kuhn in the History department who had an entirely different take on the subject than he did. So finally I learned about Kuhn and went to see him. Since Kuhn had very few students, I looked good; and I gradually I worked my way free from the Physics department and went into history. My PhD is in History; and I took a lot history courses and, as I said, history really is my interest. I’m interested in science too of course but I feel that my major concerns are historical and the writing of history is to me much more interesting and pleasant than calculations.

You entered that world at a fascinating time, when history of science – I’m sure to the surprise of most of its scholars – exploded onto the popular scene. Kuhn, Popper, Feyerabend and Lakatos suddenly appeared in The New Yorker, Life Magazine, and The Christian Century. I find that these guys are still being read, misread and misunderstood by many audiences. And that seems to be true even for their intended audiences – sometimes by philosophers and historians of science – certainly by scientists. I see multiple conflicting readings that would seem to show that at least some of them are wrong.

Well if you have two or more different readings then I guess that’s a safe conclusion. (Laughs.)

You have a problem with multiple conflicting truths…? Anyway – misreading Kuhn…

I’m more familiar with the misreading of Kuhn than of the others. I’m familiar with that because he was himself very distressed by many of the uses made of his work – particularly the notion that science is no different from art or has no stronger basis than opinion. And that bothered him a lot.

I don’t know your involvement in his work around that time. Can you tell me how you relate to what he was doing in that era?

I got my PhD under him. In fact my first work with him was hunting up footnotes for Structure. So I knew the text of the final draft well – and I knew him quite well during the initial reception of it. And then we all went off together to Copenhagen for a physics project and we were all thrown together a lot. So that was my personal connection and then of course I’ve been interested subsequently in Structure, as everybody is bound to be in my line of work. So there’s no doubt, as he says so in several places, that he was distressed by the uses made of it. And that includes uses made in the history of science particularly by the social constructionists, who try to do without science altogether or rather just to make it epiphenomenal on political or social forces.

I’ve read opinions by others who were connected with Kuhn saying there was a degree of back-peddling going by Kuhn in the 1970s. The implication there is that he really did intend more sociological commentary than he later claimed. Now I don’t see evidence of that in the text of Structure, and incidents like his telling Freeman Dyson that he (Kuhn) was not a Kuhnian would suggest otherwise. Do you have any thoughts on that?

I think that one should keep in mind the purpose of Structure, or rather the context in which it was produced. It was supposed to have been an article in this encyclopedia of unified science and Kuhn’s main interest was in correcting philosophers. He was not aiming for historians even. His message was that the philosophy practiced by a lot of positivists and their description of science was ridiculous because it didn’t pay any attention to the way science was actually done. So Kuhn was going to tell them how science was done, in order to correct philosophy. But then much to his surprise he got picked up by people for whom it was not written, who derived from it the social constructionist lesson that we’re all familiar with. And that’s why he was an unexpected rebel. But he did expect to be rebellious; that was the whole point. It’s just that the object of his rebellion was not history or science but philosophy.

So in that sense it would seem that Feyerabend’s question on whether Kuhn intended to be prescriptive versus descriptive is answered. It was not prescriptive.

Right – not prescriptive to scientists. But it was meant to be prescriptive to the philosophers – or at least normalizing – so that they would stop being silly and would base their conception of scientific progress on the way in which scientists actually went about their business. But then the whole thing got too big for him and he got into things that, in my opinion, really don’t have anything to do with his main argument. For example, the notion of incommensurability, which was not, it seems to me, in the original program. And it’s a logical construct that I don’t think is really very helpful, and he got quite hung up on that and seemed to regard that as the most important philosophical message from Structure.

I wasn’t aware that he saw it that way. I’m aware that quite a few others viewed it like that. Paul Feyerabend, in one of his last books, said that he and Kuhn kicked around this idea of commensurability in 1960 and had slightly different ideas about where to go with it. Feyerabend said Kuhn wanted to use it historically whereas his usage was much more abstract. I was surprised at the level of collaboration indicated by Feyerabend.

Well they talked a lot. They were colleagues. I remember parties at Kuhn’s house where Feyerabend would show up with his old white T shirt and several women – but that’s perhaps irrelevant to the main discussion. They were good friends. I got along quite well with Feyerabend too. We had discussions about the history of quantum physics and so on. The published correspondence between Feyerabend and Lakatos is relevant here. It’s rather interesting in that the person we’ve left out of the discussion so far, Karl Popper, was really the lighthouse for Feyerabend and Lakatos, but not for Kuhn. And I think that anybody who wants to get to the bottom of the relationship between Kuhn and Feyerabend needs to consider the guy out of the frame, who is Popper.

It appears Feyerabend was very critical of Kuhn and Structure at the time it was published. I think at that point Feyerabend was still essentially a Popperian. It seems Feyerabend reversed position on that over the next decade or so.

JH: Yes, at the time in question, around 1960, when they had these discussions, I think Feyerabend was still very much in Popper’s camp. Of course like any bright student, he disagreed with his professor about things.

How about you, as a bright student in 1960 – what did you disagree with your professor, Kuhn, about?