Posts Tagged Paul Feyerabend

After the Applause: Heilbron Rereads Feyerabend

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science, Philosophy of Science on June 4, 2025

A decade ago, in a Science, Technology and Society (STS) roundtable, I brought up Paul Feyerabend, who was certainly familiar to everyone present. I said that his demand for a separation of science and state – his call to keep science from becoming a tool of political authority – seemed newly relevant in the age of climate science and policy entanglement. Before I could finish the thought, someone cut in: “You can’t use Feyerabend to support republicanism!”

I hadn’t made an argument. Feyerabend was being claimed as someone who belonged to one side of a cultural war. His ideas were secondary. That moment stuck with me, not because I was misunderstood, but because Feyerabend was. And maybe he would have loved that. He was ambiguous by design. The trouble is that his deliberate opacity has hardened, over time, into distortion.

Feyerabend survives in fragments and footnotes. He’s the folk hero who overturned Method and danced on its ruins. He’s a cautionary tale: the man who gave license to science denial, epistemic relativism, and rhetorical chaos. You’ll find him invoked in cultural studies and critiques of scientific rationality, often with little more than the phrase “anything goes” as evidence. He’s also been called “the worst enemy of science.”

Against Method is remembered – or reviled – as a manifesto for intellectual anarchy. But “manifesto” doesn’t fit at all. It didn’t offer a vision, a list of principles, or a path forward. It has no normative component. It offered something stranger: a performance.

Feyerabend warned readers in the preface that the book would contradict itself, that it wasn’t impartial, and that it was meant to persuade, not instruct. He said – plainly and explicitly – that later parts would refute earlier ones. It was, in his words, a “tendentious” argument. And yet neither its admirers nor its critics have taken that warning seriously.

Against Method has become a kind of Rorschach test. For some, it’s license; for others, sabotage. Few ask what Feyerabend was really doing – or why he chose that method to attack Method. A few of us have long argued that Against Method has been misread. It was never meant as a guidebook or a threat, but as a theatrical critique staged to provoke and destabilize something that badly needed destabilizing.

That, I was pleased to learn, is also the argument made quietly and precisely in the last published work of historian John Heilbron. It may be the most honest reading of Feyerabend we’ve ever had.

John once told me that, unlike Kuhn, he had “the metabolism of a historian,” a phrase that struck me later as a perfect self-diagnosis: patient, skeptical, and slow-burning. He’d been at Berkeley when Feyerabend was still strutting the halls in full flair – the accent, the dramatic pronouncements, the partying. John didn’t much like him. He said so over lunch, on walks, at his house or mine. Feyerabend was hungry for applause, and John disapproved of his personal appetites and the way he flaunted them.

And yet… John’s recent piece on Feyerabend – the last thing he ever published – is microscopically delicate, charitable, and clear-eyed. John’s final chapter in Stefano Gattei’s recent book, Feyerabend in Dialogue, contains no score-settling, no demolition. Just a forensic mind trained to separate signal from noise. If Against Method is a performance, Heilbron doesn’t boo it offstage. He watches it again, closely, and tells us how it was done. Feyerabend through Heilbron’s lens is a performance reframed.

If anyone was positioned to make sense of Feyerabend, rhetorically, philosophically, and historically, it was Heilbron – Thomas Kuhn’s first graduate student, a lifelong physicist-turned-historian, and an expert on both early modern science and quantum theory’s conceptual tangles. His work on Galileo, Bohr, and the Scientific Revolution was always precise, occasionally sly, and never impressed by performance for performance’s sake.

That care is clearest in his treatment of Against Method’s most famous figure: Galileo. Feyerabend made Galileo the centerpiece of his case against scientific method – not as a heroic rationalist, but as a cunning rhetorician who won not because of superior evidence, but because of superior style. He compared Galileo to Goebbels, provocatively, to underscore how persuasion, not demonstration, drove the acceptance of heliocentrism. In Feyerabend’s hands, Galileo became a theatrical figure, a counterweight to the myth of Enlightenment rationality.

Heilbron dismantles this with the precision of someone who has lived in Galileo’s archives. He shows that while Galileo lacked a modern theory of optics, he was not blind to his telescope’s limits. He cross-checked, tested, and refined. He triangulated with terrestrial experiments. He understood that instruments could deceive, and worked around that risk with repetition and caution. The image of Galileo as a showman peddling illusions doesn’t hold up. Galileo, flaws acknowledged, was a working proto-scientist, attentive to the fragility of his tools.

Heilbron doesn’t mythologize Galileo; his 2010 Galileo makes that clear. But he rescues Galileo from Feyerabend’s caricature. In doing so, he models something Against Method never offered: a historically grounded, philosophically rigorous account of how science proceeds when tools are new, ideas unstable, and theory underdetermined by data.

To be clear, Galileo was no model of transparency. He framed the Dialogue as a contest between Copernicus and Ptolemy, though he knew Tycho Brahe’s hybrid system was the more serious rival. He pushed his theory of tides past what his evidence could support, ignoring counterarguments – even from Cardinal Bellarmine – and overstating the case for Earth’s motion.

Heilbron doesn’t conceal these. He details them, but not to dismiss. For him, these distortions are strategic flourishes – acts of navigation by someone operating at the edge of available proof. They’re rhetorical, yes, but grounded in observation, subject to revision, and paid for in methodological care.

That’s where the contrast with Feyerabend sharpens. Feyerabend used Galileo not to advance science, but to challenge its authority. More precisely, to challenge Method as the defining feature of science. His distortions – minimizing Galileo’s caution, questioning the telescope, reimagining inquiry as theater – were made not in pursuit of understanding, but in service of a larger philosophical provocation. This is the line Heilbron quietly draws: Galileo bent the rules to make a case about nature; Feyerabend bent the past to make a case about method.

In his final article, Heilbron makes four points. First, that the Galileo material in Against Method – its argumentative keystone – is historically slippery and intellectually inaccurate. Feyerabend downplays empirical discipline and treats rhetorical flourish as deception. Heilbron doesn’t call this dishonest. He calls it stagecraft.

Second, that Feyerabend’s grasp of classical mechanics, optics, and early astronomy was patchy. His critique of Galileo’s telescope rests on anachronistic assumptions about what Galileo “should have” known. He misses the trial-based, improvisational reasoning of early instrumental science. Heilbron restores that context.

Third, Heilbron credits Feyerabend’s early engagement with quantum mechanics – especially his critique of von Neumann’s no-hidden-variables proof and his alignment with David Bohm’s deterministic alternative. Feyerabend’s philosophical instincts were sharp.

And fourth, Heilbron tracks how Feyerabend’s stance unraveled – oscillating between admiration and disdain for Popper, Bohr, and even his earlier selves. He supported Bohm against Bohr in the 1950s, then defended Bohr against Popper in the 1970s. Heilbron doesn’t call this hypocrisy. He calls it instability built into the project itself: Feyerabend didn’t just critique rationalism – he acted out its undoing. If this sounds like a takedown, it isn’t. It’s a reconstruction – calm, slow, impartial. The rare sort that shows us not just what Feyerabend said, but where he came apart.

Heilbron reminds us what some have forgotten and many more never knew: that Feyerabend was once an insider. Before Against Method, he was embedded in the conceptual heart of quantum theory. He studied Bohm’s challenge to Copenhagen while at LSE, helped organize the 1957 Colston symposium in Bristol, and presented a paper there on quantum measurement theory. He stood among physicists of consequence – Bohr, Bohm, Podolsky, Rosen, Dirac, and Pauli – all struggling to articulate alternatives to an orthodoxy – Copenhagen Interpretation – that they found inadequate.

With typical wit, Heilbron notes that von Neumann’s no-hidden-variables proof “was widely believed, even by people who had read it.” Feyerabend saw that dogma was hiding inside the math – and tried to smoke it out.

Late in life, Feyerabend’s provocations would ripple outward in unexpected directions. In a 1990 lecture at Sapienza University, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger – later Pope Benedict XVI – quoted Against Method approvingly. He cited Feyerabend’s claim that the Church had been more reasonable than Galileo in the affair that defined their rupture. When Ratzinger’s 2008 return visit was canceled due to protests about that quotation, the irony was hard to miss. The Church, once accused of silencing science, was being silenced by it, and stood accused of quoting a philosopher who spent his life telling scientists to stop pretending they were priests.

We misunderstood Feyerabend not because he misled us, but because we failed to listen the way Heilbron did.

Anarchy and Its Discontents: Paul Feyerabend’s Critics

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science, Philosophy of Science on June 3, 2025

(For and against Against Method)

Paul Feyerabend’s 1975 Against Method and his related works made bold claims about the history of science, particularly the Galileo affair. He argued that science progressed not because of adherence to any specific method, but through what he called epistemological anarchism. He said that Galileo’s success was due in part to rhetoric, metaphor, and politics, not just evidence.

Some critics, especially physicists and historically rigorous philosophers of science, have pointed out technical and historical inaccuracies in Feyerabend’s treatment of physics. Here are some examples of the alleged errors and distortions:

Misunderstanding Inertial Frames in Galileo’s Defense of Copernicanism

Feyerabend argued that Galileo’s arguments for heliocentrism were not based on superior empirical evidence, and that Galileo used rhetorical tricks to win support. He claimed that Galileo simply lacked any means of distinguishing heliocentric from geocentric models empirically, so his arguments were no more rational than those of Tycho Brahe and other opponents.

His critics responded by saying that Galileo’s arguments based on the phases of Venus and Jupiter’s moons were empirically decisive against the Ptolemaic model. This is unarguable, though whether Galileo had empirical evidence to overthrow Tycho Brahe’s hybrid model is a much more nuanced matter.

Critics like Ronald Giere, John Worrall, and Alan Chalmers (What Is This Thing Called Science?) argued that Feyerabend underplayed how strong Galileo’s observational case actually was. They say Feyerabend confused the issue of whether Galileo had a conclusive argument with whether he had a better argument.

This warrants some unpacking. Specifically, what makes an argument – a model, a theory – better? Criteria might include:

- Empirical adequacy – Does the theory fit the data? (Bas van Fraassen)

- Simplicity – Does the theory avoid unnecessary complexity? (Carl Hempel)

- Coherence – Is it internally consistent? (Paul Thagard)

- Explanatory power – Does it explain more than rival theories? (Wesley Salmon)

- Predictive power – Does it generate testable predictions? (Karl Popper, Hempel)

- Fertility – Does it open new lines of research? (Lakatos)

Some argue that Galileo’s model (Copernicanism, heliocentrism) was obviously simpler than Brahe’s. But simplicity opens another can of philosophical worms. What counts as simple? Fewer entities? Fewer laws? More symmetry? Copernicus had simpler planetary order but required a moving Earth. And Copernicus still relied on epicycles, so heliocentrism wasn’t empirically simpler at first. Given the evidence of the time, a static Earth can be seen as simpler; you don’t need to explain the lack of wind and the “straight” path of falling bodies. Ultimately, this point boils down to aesthetics, not math or science. Galileo and later Newtonians valued mathematical elegance and unification. Aristotelians, the church, and Tychonians valued intuitive compatibility with observed motion.

Feyerabend also downplayed Galileo’s use of the principle of inertia, which was a major theoretical advance and central to explaining why we don’t feel the Earth’s motion.

Misuse of Optical Theory in the Case of Galileo’s Telescope

Feyerabend argued that Galileo’s use of the telescope was suspect because Galileo had no good optical theory and thus no firm epistemic ground for trusting what he saw.

His critics say that while Galileo didn’t have a fully developed geometrical optics theory (e.g., no wave theory of light), his empirical testing and calibration of the telescope were rigorous by the standards of the time.

Feyerabend is accused of anachronism – judging Galileo’s knowledge of optics by modern standards and therefore misrepresenting the robustness of his observational claims. Historians like Mario Biagioli and Stillman Drake point out that Galileo cross-verified telescope observations with the naked eye and used repetition, triangulation, and replication by others to build credibility.

Equating All Theories as Rhetorical Equals

Feyerabend in some parts of Against Method claimed that rival theories in the history of science were only judged superior in retrospect, and that even “inferior” theories like astrology or Aristotelian cosmology had equal rational footing at the time.

Historians like Steven Shapin (How to be Antiscientific) and David Wootton (The Invention of Science) say that this relativism erases real differences in how theories were judged even in Galileo’s time. While not elaborated in today’s language, Galileo and his rivals clearly saw predictive power, coherence, and observational support as fundamental criteria for choosing between theories.

Feyerabend’s polemical, theatrical tone often flattened the epistemic distinctions that working scientists and philosophers actually used, especially during the Scientific Revolution. His analysis of “anything goes” often ignored the actual disciplinary practices of science, especially in physics.

Failure to Grasp the Mathematical Structure of Physics

Scientists – those broad enough to know who Feyerabend was – often claim that he misunderstood or ignored the role of mathematics in theory-building, especially in Newtonian mechanics and post-Galilean developments. In Against Method, Feyerabend emphasizes metaphor and persuasion over mathematics. While this critique is valuable when aimed at the rhetorical and political sides of science, it underrates the internal mathematical constraints that shape physical theories, even for Galileo.

Imre Lakatos, his friend and critic, called Feyerabend’s work a form of “intellectual sabotage”, arguing that he distorted both the history and logic of physics.

Misrepresenting Quantum Mechanics

Feyerabend wrote about Bohr and Heisenberg in Philosophical Papers and later essays. Critics like Abner Shimony and Mario Bunge charge that Feyerabend misrepresented or misunderstood Bohr’s complementarity as relativistic, when Bohr’s position was more subtle and aimed at objective constraints on language and measurement.

Feyerabend certainly fails to understand the mathematical formalism underpinning Quantum Mechanics. This weakens his broader claims about theory incommensurability.

Feyerabend’s erroneous critique of Neil’s Bohr is seen in his 1958 Complimentarity:

“Bohr’s point of view may be introduced by saying that it is the exact opposite of [realism]. For Bohr the dual aspect of light and matter is not the deplorable consequence of the absence of a satisfactory theory, but a fundamental feature of the microscopic level. For him the existence of this feature indicates that we have to revise … the [realist] ideal of explanation.” (more on this in an upcoming post)

Epistemic Complaints

Beyond criticisms that he failed to grasp the relevant math and science, Feyerabend is accused of selectively reading or distorting historical episodes to fit the broader rhetorical point that science advances by breaking rules, and that no consistent method governs progress. Feyerabend’s claim that in science “anything goes” can be seen as epistemic relativism, leaving no rational basis to prefer one theory over another or to prefer science over astrology, myth, or pseudoscience.

Critics say Feyerabend blurred the distinction between how theories are argued (rhetoric) and how they are justified (epistemology). He is accused of conflating persuasive strategy with epistemic strength, thereby undermining the very principle of rational theory choice.

Some take this criticism to imply that methodological norms are the sole basis for theory choice. Feyerabend’s “anarchism” may demolish authority, but is anything left in its place except a vague appeal to democratic or cultural pluralism? Norman Levitt and Paul Gross, especially in Higher Superstition: The Academic Left and Its Quarrels with Science (1994), argue this point, along with saying Feyerabend attacked a caricature of science.

Personal note/commentary: In my view, Levitt and Gross did some great work, but Higher Superstition isn’t it. I bought the book shortly after its release because I was disgusted with weaponized academic anti-rationalism, postmodernism, relativism, and anti-science tendencies in the humanities, especially those that claimed to be scientific. I was sympathetic to Higher Superstition’s mission but, on reading it, was put off by its oversimplifications and lack of philosophical depth. Their arguments weren’t much better than those of the postmodernists. Critics of science in the humanities critics overreached and argued poorly, but they were responding to legitimate concerns in the philosophy of science. Specifically:

- Underdetermination – Two incompatible theories often fit the same data. Why do scientists prefer one over another? As Kuhn argued, social dynamics play a role.

- Theory-laden Observations – Observations are shaped by prior theory and assumptions, so science is not just “reading the book of nature.”

- Value-laden Theories – Public health metrics like life expectancy and morbidity (opposed to autonomy or quality of life) trickle into epidemiology.

- Historical Variability of Consensus – What’s considered rational or obvious changes over time (phlogiston, luminiferous ether, miasma theory).

- Institutional Interest and Incentives – String theory’s share of limited research funding, climate science in service of energy policy and social agenda.

- The Problem of Reification – IQ as a measure of intelligence has been reified in policy and education, despite deep theoretical and methodological debates about what it measures.

- Political or Ideological Capture – Marxist-Leninist science and eugenics were cases where ideology shaped what counted as science.

Higher Superstition and my unexpected negative reaction to it are what brought me to the discipline of History and Philosophy of Science.

Conclusion

Feyerabend exaggerated the uncertainty of early modern science, downplayed the empirical gains Galileo and others made, and misrepresented or misunderstood some of the technical content of physics. His mischievous rhetorical style made it hard to tell where serious argument ended and performance began. Rather than offering a coherent alternative methodology, Feyerabend’s value lay in exposing the fragility and contingency of scientific norms. He made it harder to treat methodological rules as timeless or universal by showing how easily they fracture under the pressure of real historical cases.

In a following post, I’ll review the last piece John Heilbron wrote before he died, Feyerabend, Bohr and Quantum Physics, which appeared in Stefano Gattei’s Feyerabend in Dialogue, a set of essays marking the 100th anniversary of Feyerabend’s birth.

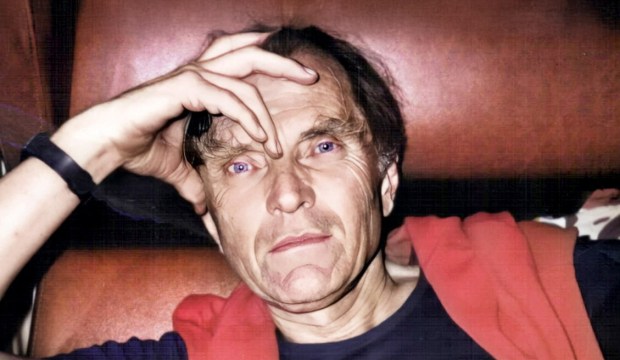

Paul Feyerabend. Photo courtesy of Grazia Borrini-Feyerabend.

John Heilbron Interview – June 2012

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science, Philosophy of Science on June 2, 2025

In 2012, I spoke with John Heilbron, historian of science and Professor Emeritus at UC Berkeley, about his career, his work with Thomas Kuhn, and the legacy of The Structure of Scientific Revolutions on its 50th anniversary. We talked late into the night. The conversation covered his shift from physics to history, his encounters with Kuhn and Paul Feyerabend, and his critical take on the direction of Science and Technology Studies (STS).

The interview marked a key moment. Kuhn and Feyerabend’s legacies were under fresh scrutiny, and STS was in the midst of redefining itself, often leaning toward sociological frameworks at the expense of other approaches.

Thirteen years later, in 2025, this commentary revisits that interview to illuminate its historical context, situate Heilbron’s critiques, and explore their relevance to contemporary STS and broader academic debates.

Over more than a decade, I had ongoing conversations with Heilbron about the evolution of the history of science – history of the history of science – and the complex relationship between History of Science and Science, Technology, and Society (STS) programs. At UC Berkeley, unlike at Harvard or Stanford, STS has long remained a “Designated Emphasis” rather than a department or standalone degree. Academic conservatism in departmental structuring, concerns about reputational risk, and questions about the epistemic rigor of STS may all have contributed to this decision. Moreover, Berkeley already boasted world-class departments in both History and Sociology.

That 2012 interview, the only one we recorded, brought together themes we’d explored over many years. Since then, STS has moved closer to engaging with scientific content itself. But it still draws criticism, both from scientists and from public misunderstanding. In 2012, the field was still heavily influenced by sociological models, particularly the Strong Programme and social constructivism, which stressed how scientific knowledge is shaped by social context. One of the key texts in this tradition, Shapin and Schaffer’s Leviathan and the Air-Pump (1985), argued that even Boyle’s experiments weren’t simply about discovery but about constructing scientific consensus.

Heilbron pushed back against this framing. He believed it sidelined the technical and epistemic depth of science, reducing STS to a sociological critique. He was especially wary of the dense, abstract language common in constructivist work. In his view, it often served as cover for thin arguments, especially from younger scholars who copied the style but not the substance. He saw it as a tactic: establish control of the conversation by embedding a set of terms, then build influence from there.

The influence of Shapin and Schaffer, Heilbron argued, created the impression that STS was dominated by a single paradigm, ironically echoing the very Kuhnian framework they analyzed. His frustration with a then-recent Isis review reflected his concern that constructivism had become doctrinaire, pressuring scholars to conform to its methods even when irrelevant to their work. His reference to “political astuteness” pointed to the way in which key figures in the field successfully advanced their terminology and frameworks, gaining disproportionate influence. While this gave them intellectual clout, Heilbron saw it as a double-edged sword: it strengthened their position while encouraging dogmatism among followers who prioritized jargon over genuine analysis.

Bill Storage: How did you get started in this curious interdisciplinary academic realm?

John Heilbron: Well, it’s not really very interesting, but I was a graduate student in physics but my real interest was history. So at some point I went down to the History department and found the medievalist, because I wanted to do medieval history. I spoke with the medievalist ad he said, “well, that’s very charming but you know the country needs physicists and it doesn’t need medievalists, so why don’t you go back to physics.” Which I duly did. But he didn’t bother to point out that there was this guy Kuhn in the History department who had an entirely different take on the subject than he did. So finally I learned about Kuhn and went to see him. Since Kuhn had very few students, I looked good; and I gradually I worked my way free from the Physics department and went into history. My PhD is in History; and I took a lot history courses and, as I said, history really is my interest. I’m interested in science too of course but I feel that my major concerns are historical and the writing of history is to me much more interesting and pleasant than calculations.

You entered that world at a fascinating time, when history of science – I’m sure to the surprise of most of its scholars – exploded onto the popular scene. Kuhn, Popper, Feyerabend and Lakatos suddenly appeared in The New Yorker, Life Magazine, and The Christian Century. I find that these guys are still being read, misread and misunderstood by many audiences. And that seems to be true even for their intended audiences – sometimes by philosophers and historians of science – certainly by scientists. I see multiple conflicting readings that would seem to show that at least some of them are wrong.

Well if you have two or more different readings then I guess that’s a safe conclusion. (Laughs.)

You have a problem with multiple conflicting truths…? Anyway – misreading Kuhn…

I’m more familiar with the misreading of Kuhn than of the others. I’m familiar with that because he was himself very distressed by many of the uses made of his work – particularly the notion that science is no different from art or has no stronger basis than opinion. And that bothered him a lot.

I don’t know your involvement in his work around that time. Can you tell me how you relate to what he was doing in that era?

I got my PhD under him. In fact my first work with him was hunting up footnotes for Structure. So I knew the text of the final draft well – and I knew him quite well during the initial reception of it. And then we all went off together to Copenhagen for a physics project and we were all thrown together a lot. So that was my personal connection and then of course I’ve been interested subsequently in Structure, as everybody is bound to be in my line of work. So there’s no doubt, as he says so in several places, that he was distressed by the uses made of it. And that includes uses made in the history of science particularly by the social constructionists, who try to do without science altogether or rather just to make it epiphenomenal on political or social forces.

I’ve read opinions by others who were connected with Kuhn saying there was a degree of back-peddling going by Kuhn in the 1970s. The implication there is that he really did intend more sociological commentary than he later claimed. Now I don’t see evidence of that in the text of Structure, and incidents like his telling Freeman Dyson that he (Kuhn) was not a Kuhnian would suggest otherwise. Do you have any thoughts on that?

I think that one should keep in mind the purpose of Structure, or rather the context in which it was produced. It was supposed to have been an article in this encyclopedia of unified science and Kuhn’s main interest was in correcting philosophers. He was not aiming for historians even. His message was that the philosophy practiced by a lot of positivists and their description of science was ridiculous because it didn’t pay any attention to the way science was actually done. So Kuhn was going to tell them how science was done, in order to correct philosophy. But then much to his surprise he got picked up by people for whom it was not written, who derived from it the social constructionist lesson that we’re all familiar with. And that’s why he was an unexpected rebel. But he did expect to be rebellious; that was the whole point. It’s just that the object of his rebellion was not history or science but philosophy.

So in that sense it would seem that Feyerabend’s question on whether Kuhn intended to be prescriptive versus descriptive is answered. It was not prescriptive.

Right – not prescriptive to scientists. But it was meant to be prescriptive to the philosophers – or at least normalizing – so that they would stop being silly and would base their conception of scientific progress on the way in which scientists actually went about their business. But then the whole thing got too big for him and he got into things that, in my opinion, really don’t have anything to do with his main argument. For example, the notion of incommensurability, which was not, it seems to me, in the original program. And it’s a logical construct that I don’t think is really very helpful, and he got quite hung up on that and seemed to regard that as the most important philosophical message from Structure.

I wasn’t aware that he saw it that way. I’m aware that quite a few others viewed it like that. Paul Feyerabend, in one of his last books, said that he and Kuhn kicked around this idea of commensurability in 1960 and had slightly different ideas about where to go with it. Feyerabend said Kuhn wanted to use it historically whereas his usage was much more abstract. I was surprised at the level of collaboration indicated by Feyerabend.

Well they talked a lot. They were colleagues. I remember parties at Kuhn’s house where Feyerabend would show up with his old white T shirt and several women – but that’s perhaps irrelevant to the main discussion. They were good friends. I got along quite well with Feyerabend too. We had discussions about the history of quantum physics and so on. The published correspondence between Feyerabend and Lakatos is relevant here. It’s rather interesting in that the person we’ve left out of the discussion so far, Karl Popper, was really the lighthouse for Feyerabend and Lakatos, but not for Kuhn. And I think that anybody who wants to get to the bottom of the relationship between Kuhn and Feyerabend needs to consider the guy out of the frame, who is Popper.

It appears Feyerabend was very critical of Kuhn and Structure at the time it was published. I think at that point Feyerabend was still essentially a Popperian. It seems Feyerabend reversed position on that over the next decade or so.

JH: Yes, at the time in question, around 1960, when they had these discussions, I think Feyerabend was still very much in Popper’s camp. Of course like any bright student, he disagreed with his professor about things.

How about you, as a bright student in 1960 – what did you disagree with your professor, Kuhn, about?

Well I believe in the proposition that philosophers and historians have different metabolisms. And I’m metabolically a historian and Kuhn was metabolically a philosopher – even though he did write history. But his most sustained piece of history of science was his book on black body theory; and that’s very narrowly intellectualist in approach. It’s got nothing to do with the themes of the structure of scientific revolutions – which does have something to say for the historian – but he was not by practice a historian. He didn’t like a whole lot of contingent facts. He didn’t like archival and library work. His notion of fun was take a few texts and just analyze and reanalyze them until he felt he had worked his way into the mind of their author. I take that to be a necromantic feat that’s not really possible.

I found that he was a very clever guy and he was excellent as a professor because he was very interested in what you were doing as soon it was something he thought he could make some use of. And that gave you the idea that you were engaged in something important, so I must give him that. On the other hand he just didn’t have the instincts or the knowledge to be a historian and so I found myself not taking much from his own examples. Once I had an argument with him about some way of treating a historical subject and I didn’t feel that I got anything out of him. Quite the contrary; I thought that he just ducked all the interesting issues. But that was because they didn’t concern him.

James Conant, president of Harvard who banned communists, chair of the National Science Foundation, etc.: how about Conant’s influence on Structure?

It’s not just Conant. It was the whole Harvard circle, of which Kuhn was part. There was this guy, Leonard Nash; there was Gerald Holton. And these guys would get together and l talk about various things having to do with the relationship between science and the public sphere. It was a time when Conant was fighting for the National Science Foundation and I think that this notion of “normal science” in which the scientists themselves must be left fully in charge of what they’re doing in order to maximize the progress within the paradigm to bring the profession swiftly to the next revolution – that this is essentially the Conant doctrine with respect to the ground rules of the National Science Foundation, which is “let the scientists run it.” So all those things were discussed. And you can find many bits of Kuhn’s Structure in that discussion. For example, the orthodoxy of normal science in, say, Bernard Cohen, who didn’t make anything of it of course. So there’s a lot of this Harvard group in Structure, as well as certain lessons that Kuhn took from his book on the Copernican Revolution, which was the textbook for the course he gave under Conant. So yes, I think Conant’s influence is very strong there.

So Kuhn was ultimately a philosopher where you are a historian. I think I once heard you say that reading historical documents does not give you history.

Well I agree with that, but I don’t remember that I was clever enough to say it.

Assuming you said it or believe it, then what does give you history?

Well, reading them is essential, but the part contributed by the historian is to make some sense of all the waste paper he’s been reading. This is essentially a construction. And that’s where the art, the science, the technique of the historian comes into play, to try to make a plausible narrative that has to satisfy certain rules. It can’t go against the known facts and it can’t ignore the new facts that have come to light through the study of this waste paper, and it can’t violate rules of verisimilitude, human action and whatnot. But otherwise it’s a construction and you’re free to manipulate your characters, and that’s what I like about it.

So I take it that’s where the historian’s metabolism comes into play – avoidance of leaping to conclusions with the facts.

True, but at some point you’ve got to make up a story about those facts.

Ok, I’ve got a couple questions on the present state of affairs – and this is still related to the aftermath of Kuhn. From attending colloquia, I sense that STS is nearly a euphemism for sociology of science. That bothers me a bit, possibly because I’m interested in the intersection of science, technology and society. Looking at the core STS requirements on Stanford’s website, I see few courses listed that would give a student any hint of what science looks like from the inside.

I’m afraid you’re only too right. I’ve got nothing against sociology of science, the study of scientific institutions, etc. They’re all very good. But they’re tending to leave the science out, and in my opinion, the further they get from science, the worse their arguments become. That’s what bothers me perhaps most of all – the weakness of the evidentiary base of many of the arguments and conclusions that are put forward.

I thought we all learned a bit from the Science Wars – thought that sort of indeterminacy of meaning and obfuscatory language was behind us. Either it’s back, or it never went away.

Yeah, the language part is an important aspect of it, and even when the language is relatively comprehensible as I think it is in, say, constructivist history of science – by which I mean the school of Schaffer and Shapin – the insistence on peculiar argot becomes a substitute for thought. You see it quite frequently in people less able than those two guys are, who try to follow in their footsteps. You get words strung together supposedly constituting an argument but which in fact don’t. I find that quite an interesting aspect of the business, and very astute politically on the part of those guys because if you can get your words into the discourse, why, you can still hope to have influence. There’s a doctrinaire aspect to it. I was just reading the current ISIS favorable book review by one of the fellow travelers of this group. The book was not written by one of them. The review was rather complimentary but then at the end says it is a shame that this author did not discuss her views as related to Schaffer and Shapin. Well, why the devil should she? So, yes, there’s issues of language, authority, and poor argumentation. STS is afflicted by this, no doubt.

Dialogue Concerning a Cup of Cooked Collards

Posted by Bill Storage in Fiction, History of Science on May 27, 2025

in which the estimable Signora Sagreda, guided by the lucid reasoning of Salviatus and the amiable perplexities of Simplicius, doth inquire into the nature of culinary measurement, and wherein is revealed, by turns comic and calamitous, the logical dilemma and profound absurdity of quantifying cooked collards by volume, exposing thereby the nutritional fallacies, atomic impossibilities, and epistemic mischiefs that attend such a practice, whilst invoking with reverence the spectral wisdom of Galileo Galilei.

Scene: A modest parlor, with a view into a well-appointed kitchen. A pot of collards simmers.

Sagreda: Good sirs, I am in possession of a recipe, inherited from a venerable aunt, which instructs me to add one cup of cooked collards to the dish. Yet I find myself arrested by perplexity. How, I ask, can one trust such a measure, given the capricious nature of leaves once cooked?

Salviatus: Ah, Signora, thou hast struck upon a question of more gravity than may at first appear. In that innocent-seeming phrase lies the germ of chaos, the undoing of proportion, and the betrayal of consistency.

Simplicius: But surely, Salviatus, a cup is a cup! Whether one deals with molasses, barley, or leaves of collard! The vessel measures equal, does it not?

Salviatus: Ah, dear Simplicius, how quaint thy faith in vessels. Permit me to elaborate with the fullness this foolishness begs. A cup, as used here, is a measure of volume, not mass. Yet collards, when cooked, submit themselves to the will of the physics most violently. One might say that a plenty of raw collards, verdant and voluminous, upon the fire becomes but a soggy testament to entropy.

Sagreda: And yet if I, with ladle in hand, press them lightly, I may fill a cup with tender grace. But if I should tamp them down, as a banker tamps tobacco, I might squeeze thrice more into the same vessel.

Salviatus: Just so! And here lies its absurdity. The recipe calls for a cup, as though the collards were flour, or water, or some polite ingredient that hold the law of uniformity. But collards — and forgive my speaking plainly — are rogues. One cook’s gentle heap is another’s aggressive compression. Thus, a recipe using such a measure becomes not a method, but a riddle, a culinary Sphinx.

Simplicius: But might not tradition account for this? For is it not the case that housewives and cooks of yore prepared these dishes with their senses and not with scales?

Salviatus: A fair point, though flawed in its application. While the tongue and eye may suffice for the seasoned cook, the written recipe aspires to universality. It must serve the neophyte, the scholar, the gentleman abroad who seeks to replicate his mother’s collard pie with exactitude. And for these noble aims, only the scale may speak truth. Grams! Ounces! Units immutable, not subject to whim or squish!

Sagreda: You speak as though the collards, once cooked, engage in a deceit, cloaking their true nature.

Salviatus: Precisely. Cooked collards are like old courtiers — soft, pliable, and accustomed to hiding their substance beneath a veneer of humility. Only by weight can one know their worth. Or, more precisely, by its mass, the measure we know to not affect the rate at which objects fall.

Simplicius: But if all this be so, then is not every cookbook a liar? Is not every recipe suspect?

Salviatus: Not every recipe — only those who trade in volumetric folly where mass would bring enlightenment. The fault lies not in the recipe’s heart, but in its measurement. And this, dear Simplicius, we may yet amend.

Sagreda: Then shall we henceforth mark in our books, “Not a cup, but a weight; not a guess, but a truth“? For a measure of collards, like men, must be judged not by appearance, but by their substance.

Sagreda (reflecting): And yet, gentlemen, if I may permit a musing most unorthodox, does not all this emphasis on precision edge us perilously close to an unyielding, mechanical conception of science? Dare we call it… dogmatic?

Simplicius: Dogmatic? You surprise me, Signora. I thought it only the religion of Bellarmino and Barberini could carry such a charge.

Salviatus: Ha! Then you have not read the scribblings of Herr Paulus Feyerabend, who, proclaims with no small glee — and with more than of a trace of Giordano Bruno — that anything goes in the pursuit of knowledge. He teaches that the science, when constrained by method, becomes no different from myth.

Sagreda: Fascinating! And would this Feyerabend defend, then, the use of “a cup of cooked collards” as a sound epistemic act?

Salviatus: Indeed, he might. He would argue that inexactitude, even vagueness, can have its place. That Sagreda’s venerable aunt, the old wives, the village cooks, with their pinches and handfuls and mysteriously gestured “quanta bastas,” have no less a claim to truth than a chef armed with scales and thermocouples. He might well praise the “cup of cooked collards” as a liberating epistemology, a rejection of culinary tyranny.

Simplicius: Then Feyerabend would have me trust Sagreda’s aunt over the chemist?

Salviatus: Just so — he would, and be half right at least! Feyerabend’s quarrel is not with truth, but with monopoly over its definition. He seeks not the destruction of science, but the dethronement of science enthroned as sacred law. In this spirit, he might say: “Let the collards be measured by weight, or not at all, for the joy of the dish may reside not in precision, but in a dance of taste and memory.”

Sagreda: A heady notion! And perhaps, like a stew, the truth lies in the balance — one must permit both the grammar of measurement and the poetry of intuition. The recipe, then, is both science and art, its ambiguity not a flaw, but sometimes an invitation.

Salviatus: Beautifully said, Signora. Yet let us remember: Feyerabend champions chaos as a remedy for tyranny, not as an end in itself. He might defend the cook who ignores the scale, but not the recipe which claims false precision where none is due. And so, if we declare “a cup of cooked collards,” we ought either to define it, or admit with humility that we have no idea how many leaves is right to each observer.

Simplicius: Then science and the guessing of aunts may coexist — so long as neither pretends to be the other?

Salviatus: Precisely. The scale must not scorn the hunch, nor the cup dethrone the scale. But let us not forget: when preparing a dish to be replicated, mass is our anchor in the storm of leafy deception.

Sagreda (opening her laptop): Ah! Then let us dedicate this dish — to Feyerabend, to Bruno, to my venerable aunt. I will append to her recipe, notations from these reasonings on contradiction and harmony.

Cooked collards are like old courtiers — soft, pliable, and accustomed to hiding their substance beneath a veneer of humility — Salviatus

Sagreda (looking up from her laptop with astonishment): Gentlemen! I have stumbled upon a most curious nutritional claim. This USDA document — penned by government scientist or rogue dietitian — declares with solemn authority that a cup of cooked collards contains 266 grams calcium and a cup raw only 52.

Salviatus (arching an eyebrow): More calcium? From whence, pray, does this mineral bounty emerge? For collards, like men, cannot give what they do not possess.

Simplicius (waving a wooden spoon): It is well known, is it not, that cooking enhances healthfulness? The heat releases the virtues hidden within the leaf, like Barberini stirring the piety of his reluctant congregation!

Salviatus: Simplicius, your faith outpaces your chemistry. Let us dissect this. Calcium, as an element, is not born anew in the pot. It is not conjured by flame nor summoned by steam. It is either present, or it is not.

Simplicius: So how, then, can it be that the cooked collards have more calcium than their raw counterparts — cup for cup?

Sagreda: Surely, again, the explanation is compression. The cooking drives out water, collapses volume, and fills the cup more densely with matter formerly bulked by air and hubris.

Salviatus: Exactly so! A cup of cooked collards is, in truth, the compacted corpse of many cups raw — and with them, their calcium. The mineral content has not changed; only the volume has bowed before heat’s stern hand.

Simplicius: But surely the USDA, a most probable power, must be seen as sovereign on the matter. Is there no means, other than admitting the slackness of their decree, by which we can serve its authority?

Salviatus: Then, Simplicius, let us entertain absurdity. Suppose for a moment — as a thought experiment — that the cooking process does, in fact, create calcium.

By what alchemy? What transmutation?

Let us assume, in a spirit of lunatic (and no measure anachronous) generosity, that the humble collard leaf contains also magnesium — plentiful, impudent magnesium — and that during cooking, it undergoes nuclear transformation. Though they have the same number of valence electrons, to turn magnesium (atomic number 12) into calcium (atomic number 20), we must add 8 protons and a healthy complement of neutrons.

Sagreda: But whence come these subatomic parts? Shall we pluck nucleons from the steam?

Salviatus (solemnly): We must raid the kitchen for protons as a burglar raids a larder. Perhaps the protons are drawn from the salt, or the neutrons from baking powder, or perhaps our microwave is a covert collider, transforming our soup pot into CERN-by-candlelight.

But alas — this would take more energy than a dozen suns, and the vaporizing of the collards in a burst of gamma rays, leaving not calcium-rich greens but a crater and a letter of apology due. But, we know, do we not, that the universe is indifferent to apology; the earth still goes round the sun.

Sagreda: Then let us admit: the calcium remains the same. The difference is illusion — an artifact of measurement, not of matter.

Salviatus: Precisely. And the USDA, like other sovereigns, commits nutritional sophistry — comparing unlike volumes and implying health gained by heat alone, or, still worse, that we hold it true by unquestioned authority.

Let this be our final counsel: whenever the cup is invoked, ask, “Cup of what?” If it be cooked, know that you measure the ghost of raw things past, condensed, wilted, and innocent of transmutation.

The scale must not scorn the hunch, nor the cup dethrone the scale. – Salviatus

Thus ends the matter of the calcium-generating cauldron, in which it hath been demonstrated to the satisfaction of reason and the dismay of the USDA that no transmutation of elements occurs in the course of stewing collards, unless one can posit a kitchen fire worthy of nuclear alchemy; and furthermore, that the measure of leafy matter must be governed not by the capricious vulgarity of volume, but by the steady hand of mass, or else be entrusted to the most excellent judgment of aunts and cooks, whose intuitive faculties may triumph over quantification outright. The universe, for its part, remains intact, and the collards, alas, are overcooked.

Giordano Bruno discusses alchemy with Paul Feyerabend. Campo de’ Fiori, Rome, May 1591.

Galileo’s Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems is a proto-scientific work presented as a conversation among three characters: Salviati, Sagredo, and Simplicio. It compares the Copernican heliocentric model (Earth revolves around Sun) and the traditional Ptolemaic geocentric model (Earth as center). Salviati represents Galileo’s own views and advocates for the Copernican system, using logic, mathematics, observation, and rhetoric. Sagredo is an intelligent, neutral layman who asks questions and weighs the arguments, representing the open-minded reader. Simplicio, a supporter of Aristotle and the geocentric model held by the church, struggles to defend his views and is portrayed as naive. Through their discussion, Galileo gives evidence for the heliocentric model and critiques the shortcomings of the geocentric, making a strong case for scientific reasoning based on observation rather than tradition and authority. Cardinal Roberto Bellarmino and Maffeo Barberini (Pope Urban VIII) were the central clergy figures in Galileo’s trial. In 1970 Paul Feyerabend argued that modern institutional science resembled the church more than it did Galileo. The Dominican monk, Giordano Bruno, held unorthodox ideas in science and theology. Bellarmino framed the decision leading to his conviction of heresy in 1600. He was burned at the stake in the plaza of Campo de’ Fiori, where I stood not one hour before writing this.

Galileo with collard vendors in Pisa

Extraordinary Popular Miscarriages of Science (part 1)

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science, Uncategorized on January 18, 2024

By Bill Storage, Jan. 18, 2024

I’ve been collecting examples of bad science. Many came from friends and scientists I’ve talked to. Bad science can cover several aspects of science depending on what one means by science. At least three very different things are called science now:

- An approach or set of rules and methods used to understand and predict nature

- A body of knowledge about nature and natural processes

- An institution, culture or community of people, including academic, government and corporate professionals, who are involved, or are said to be involved, in 1. or 2. above

Many of my examples of bad science fall under the 3rd category and involve, or are dominated by, the academicians, government offices, and corporations. Below are a few of my favorites from the past century or so. I think many people tend to think that bad science happened in medieval times and that the modern western world is immune to that sort of thing. On the contrary, bad science may be on the rise. For the record, I don’t judge a theory bad merely because it was shown to be wrong, even if spectacularly wrong. Geocentricity was a good theory. Phlogiston (17th century theoretical substance believed to escape from matter during combustion), caloric theory (18th century theory of a weightless fluid that flows from hot matter to cold), and the luminiferous ether (17-19th century postulated medium for the propagation of light waves) were all good theories, though we now have robust evidence against them. All had substantial predictive power. All posited unobservable entities to explain phenomena. But predictive success alone cannot justify belief in unobservable entities. Creation science and astrology were always bad science.

To clarify the distinction between bad science and wrong theories, consider Trofim Lysenko. He was nominally a scientist. Some of his theories appear to be right. He wore the uniform, held the office, and published sciencey papers. But he did not behave scientifically (consistent with definition 1 above) when he ignored the boundless evidence and prior art about heredity. Wikipedia dubs him a pseudoscientist, despite his having some successful theories and making testable hypotheses. Pseudoscience, says Wikipedia, makes unfalsifiable claims. Lysenko’s bold claims were falsifiable, and they were falsified. Wikipedia talks as if the demarcation problem – knowing science from pseudoscience – is a closed case. Nah. Rather than tackle that matter of metaphysics and philosophy, I’ll offer that Lysenkoism, like creation science, and astrology, are all sciences but they are bad science. While they all make some testable predictions, they also make a lot of vague ones, their interest in causation is puny, and their research agendas are scant.

Good science entails testable, falsifiable theories and bold predictions. Most philosophers of science, notably excluding Karl Popper, who thought that only withstanding falsification mattered, have held that making succinct, correct prediction makes a theory good, and that successful theories make for good science. Larry Laudan gave, in my view, a fine definition of a successful theory in his 1984 Philosophy of Science: A theory is successful provided it makes substantially more correct predictions, that it leads to efficacious interventions in the natural order, or that it passes a suitable battery of tests.

Concerns over positing unobservables opens a debate on the question of just how observable are electrons, quarks, and the Higgs Field. Not here though. I am more interested in bad science (in the larger senses of science) than I am with wrong theories. Badness often stems not from seeking to explain and predict nature and failing out of refusal to read the evidence fairly, but from cloaking a non-scientific agenda in the trappings of science. I’m interested in what Kuhn, Feyerabend, and Lakatos dealt with – the non-scientific interests of academicians, government offices, and corporations and their impact on what gets studied and how it gets studied, how confirming evidence is sought and processed, how disconfirming evidence is processed, avoided, or dismissed, and whether Popperian falsifiability was ever on the table.

Recap of Kuhn, Feyerabend, and Lakatos

Thomas Kuhn claimed that normal (day-to-day lab-coat) science consisted of showing how nature can be fit into the existing theory. That is, normal science is decidedly unscientific. It is bad science, aimed at protecting the reigning paradigm from disconfirming evidence. On Kuhn’s view, your scientific education teaches you how to see things as your field requires them to be seen. He noted that medieval and renaissance astronomers never saw the supernovae that were seen in China. Europeans “knew” that the heavens were unchanging. Kuhn used the terms dogma and indoctrination to piss off scientists of his day. He thought that during scientific crises (Newton vs. Einstein being the exemplar) scientists clutched at new theories, often irrationally, and then vicious competition ended when scientific methods determined the winner of a new paradigm. Kuhn was, unknown to most of his social-science groupies, a firm believer that the scientific enterprise ultimately worked. Kuhn says normal science is bad science. He thought this was okay because crisis science reverted to good science, and in crisis, the paradigm was overthrown when the scientists got interested in philosophy of science. When Kuhn was all the rage in the early 1960s, radical sociologists of science, all at the time very left leaning, had their doubts that science could stay good under the influence of government and business. Recall worries about the military industrial complex. They thought that interest, whether economic or political, could keep science bad. I think history has sided with those sociologists; though today’s professional sociologists, now overwhelmingly employed by the the US and state governments, are astonishingly silent on the matter. Granting, for sake of argument, that social science is science, its practitioners seem to be living proof that interest can dominate not only research agendas but what counts as evidence, along with the handling of evidence toward what becomes dogma in the paradigm.

Paul Feyerabend, though also no enemy of science, thought Kuhn stopped short of exposing the biggest problems with science. Feyerabend called science, referring to science as an institution, a threat to democracy. He called for “a separation of state and science just as there is a separation between state and religious institutions.” He thought that 1960s institutional science resembled more the church of Galileo’s day than it resembled Galileo. Feyerabend thought theories should be tested against each other, not merely against the world. He called institutional science a threat because it increasingly held complete control over what is deemed scientifically important for society. Historically, he observed, individuals, by voting with their attention and their dollars, have chosen what counts as being socially valuable. Feyerabend leaned rather far left. In my History of Science appointment at UC Berkeley I was often challenged for invoking him against bad-science environmentalism because Feyerabend wouldn’t have supported a right-winger. Such is the state of H of S at Berkeley, now subsumed by Science and Technology Studies, i.e., same social studies bullshit (it all ends in “Studies”), different pile. John Heilbronn rest in peace.

Imre Lakatos had been imprisoned by the Nazis for revisionism. Through that experience he saw Kuhn’s assent of the relevant community as a valid criterion for establishing a new post-crisis paradigm as not much of a virtue. It sounded a bit too much like Nazis and risked becoming “mob psychology.” If the relevant community has excessive organizational or political power, it can put overpowering demands on individual scientists and force them to subordinate their ideas to the community (see String Theory’s attack on Lee Smolin below). Lakatos saw the quality of a science’s research agenda as a strong indicator of quality. Thin research agendas, like those of astrology and creation science, revealed bad science.

Selected Bad Science

Race Science and Eugenics

Eugenics is an all time favorite, not just of mine. It is a poster child for evil-agenda science driven by a fascist. That seems enough knowledge of the matter for the average student of political science. But eugenics did not emerge from fascism and support for it was overwhelming in progressive circles, particularly in American universities and the liberal elite. Alfred Binet of IQ-test fame, H. G. Wells, Margaret Sanger, John Harvey Kellogg, George Bernard Shaw, Theodore Roosevelt, and apparently Oliver Wendell Holmes, based on his decision that compulsory sterilization was within a state’s rights, found eugenics attractive. Financial support for the eugenics movement included the Carnegie Foundation, Rockefeller Institute, and the State Department. Harvard endorsed it, as did Stanford’s first president, David S Jordan. Yale’s famed economist and social reformer Irving Fisher was a supporter. Most aspects of eugenics in the United States ended abruptly when we discovered that Hitler had embraced it and was using it to defend the extermination of Jews. Hitler borrowed from our 1933 Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Defective Offspring drawn up by Harry Laughlin. Eugenics was a class case of advocates and activists, clueless of any sense of science, broadcasting that the science (the term “race science” exploded onto the scene as if if had always been a thing) had been settled. In an era where many Americans enjoy blaming the living – and some of the living enjoy accepting that blame – for the sins of our fathers, one wonders why these noble academic institutions have not come forth to offer recompense for their eugenics transgressions.

The War on Fat

In 1977 a Senate committee led by George McGovern published “Dietary Goals for the United States,” imploring us to eat less red meat, eggs, and dairy products. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) then issued its first dietary guidelines, which focused on cutting cholesterol and not only meat fat but fat from any source. The National Institutes of Health recommended that all Americans, including young kids, cut fat consumption. In 1980 the US government broadcast that eating less fat and cholesterol would reduce your risk of heart attack. Evidence then and ever since has not supported this edict. A low-fat diet was alleged to mitigate many metabolic risk factors and to be essential for achieving a healthy body weight. However, over the past 45 years, obesity in the US climbed dramatically while dietary fat levels fell. Europeans with higher fat diets, having the same genetic makeup, are far thinner. The science of low-fat diets and the tenets of related institutions like insurance, healthcare, and school lunches have seemed utterly immune to evidence. Word is finally trickling out. The NIH has not begged pardon.

The DDT Ban

Rachel Carson appeared before the Department of Commerce in 1963, asking for a “Pesticide Commission” to regulate the DDT. Ten years later, Carson’s “Pesticide Commission” became the Environmental Protection Agency, which banned DDT in the US. The rest of the world followed, including Africa, which was bullied by European environmentalists and aid agencies to do so.

By 1960, DDT use had eliminated malaria from eleven countries. Crop production, land values, and personal wealth rose. In eight years of DDT use, Nepal’s malaria rate dropped from over two million to 2,500. Life expectancy rose from 28 to 42 years.

Malaria reemerged when DDT was banned. Since the ban, tens of millions of people have died from malaria. Following Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring narrative, environmentalists claimed that, with DDT, cancer deaths would have negated the malaria survival rates. No evidence supported this. It was fiction invented by Carson. The only type of cancer that increased during DDT use in the US was lung cancer, which correlated cigarette use. But Carson instructed citizens and governments that DDT caused leukemia, liver disease, birth defects, premature births, and other chronic illnesses. If you “know” that DDT altered the structure of eggs, causing bird populations to dwindle, it is Carson’s doing.

Banning DDT didn’t save the birds, because DDT wasn’t the cause of US bird death as Carson reported. While bird populations had plunged prior to DDT’s first use, the bird death at the center of her impassioned plea never happened. We know this from bird count data and many subsequent studies. Carson, in her work at Fish and Wildlife Service and through her participation in Audubon bird counts, certainly knew that during US DDT use, the eagle population doubled, and robin, dove, and catbird counts increased by 500%. Carson lied like hell and we showered her with praise and money. Africans paid with their lives.

In 1969 the Environmental Defense Fund demanded a hearing on DDT. The 8-month investigation concluded DDT was not mutagenic or teratogenic. No cancer, no birth defects. In found no “deleterious effect on freshwater fish, estuarine organisms, wild birds or other wildlife.” Yet William Ruckleshaus, first director of the EPA, who never read the transcript, chose to ban DDT anyway. Joni Mitchell was thrilled. DDT was replaced by more harmful pesticides. NPR, the NY Times, and the Puget Sound Institute still report a “preponderance of evidence” of DDT’s dangers.

When challenged with the claim that DDT never killed kids, the Rachel Carson Landmark Alliance responded in 2017 that indeed it had. A two-year old drank and ounce of 5% DDT in a solution of kerosene and died. Now there’s scientific integrity.

Vilification of Cannabis

I got this one from my dentist; I had never considered it before. White-collar, or rather, work-from-home, California potheads think this problem has been overcome. Far from it. Cannabis use violates federal law. Republicans are too stupid to repeal it, and Democrats are too afraid of looking like hippies. According to Quest Diagnostics, in 2020, 4.4% of workers failed their employers’ drug tests. Blue-collar Americans, particularly those who might be a sub-sub-subcontractor on a government project, are subject to drug tests. Testing positive for weed can cost you your job. So instead of partying on pot, the shop floor consumes immense amounts of alcohol, increasing its risk of accidents at work and in the car, harming its health, and raising its risk of hard drug use. To the admittedly small sense in which the concept of a gateway drug is valid, marijuana is probably not one and alcohol almost certainly is. Racism, big pharma lobbyists, and social-control are typically blamed for keeping cannabis illegal. Governments may also have concluded that tolerating weed at the state level while maintaining federal prohibition is an optimal tax revenue strategy. Cannabis tolerance at state level appears to have reduced opioid use and opioid related ER admissions.

Stoners who scoff at anti-cannabis propaganda like Reefer Madness might be unaware that a strong correlation between psychosis and cannabis use has been known for decades. But inferring causation from that correlation was always either highly insincere (huh huh) or very bad science. Recent analysis of study participants’ genomes showed that those with the strongest genetic profile for schizophrenia were also more likely to use cannabis in large amounts. So unless you follow Lysenko, who thought acquired traits were passed to offspring, pot is unlikely to cause psychosis. When A and B correlate, either A causes B, B causes A, or C causes both, as appears to be the case with schizophrenic potheads.

To be continued.

Deficient Discipleship in Environmental Science

Posted by Bill Storage in Commentary, Philosophy of Science on October 28, 2025

Bear with me here.

Daniel Oprean’s “Portraits of Deficient Discipleship” (Kairos, 2024) argues that Gospel Matthew 8:18–27 presents three kinds of failed or immature discipleship, each corrected by Jesus’s response.

Oprean reads Matthew 19–20 as discipleship without costs. The “enthusiastic scribe” volunteers to follow Jesus but misunderstands the teacher he’s addressing. His zeal lacks awareness of cost. Jesus’s lament about having “nowhere to lay his head,” Oprean says, reveals that true discipleship entails homelessness, marginalization, and suffering.

As an instance of discipleship without commitment (vv. 21–22), a second disciple hesitates. His request to bury his father provokes Jesus’s radical command: “Follow me, and let the dead bury their own dead.” Oprean takes this as divided loyalty, a failure of commitment even among genuine followers.

Finally comes discipleship without hardships (vv. 23–27). The boat-bound disciples obey but panic in the storm. Their fear shows lack of trust. Jesus rebukes their “little faith.” His calming of the sea becomes a paradigm of faith maturing only through trial.

Across these scenes, Matthew’s Jesus confronts enthusiasm without realism, religiosity without surrender, faith without endurance. Authentic discipleship, Oprean concludes, must include cost, commitment, and hardship.

Oprean’s essay is clear and perfectly conventional evangelical exegesis. The tripartite symmetry – cost, commitment, hardship – works neatly, though it imposes a moral taxonomy on what Matthew presents as narrative tension (a pale echo of Mark’s deeper ironies). Each scene may concern not moral failure but stages of revelation: curiosity, obedience, awe. By moralizing them, Oprean flattens Matthew’s literary dynamism and theological ambiguity for devotional ends.

His dependence on the standard commentators – Gundry, Keener, Bruner – keeps him in the well-worn groove. There’s no attention to Matthew’s redactional strategy, the eschatological charge of “Son of Man” in v. 20, or the symbolic link between the sea miracle and Israel’s deliverance. The piece is descriptive, not interpretive; homiletic rather than analytic. The unsettling portrait of discipleship becomes a sermon outline about piety instead of a crisis in perception.

Fair enough, you say – there’s nothing wrong with devotional writing. True. The problem is devotional writing costumed as analysis and published as scholarship. He isn’t interrogating the text. If he were, he’d ask: Why does Matthew place these episodes together? How does “Son of Man” invoke Danielic or apocalyptic motifs? What does the sea episode reveal about Jesus’s authority over creation itself? Instead, Oprean turns inward, toward exhortation.

It’s an odd hybrid genre – half sermon, half commentary – anchored in evangelical assumptions about the text’s unity and moral purpose. Critical possibilities are excluded from the start. There’s no discussion of redactional intent, no engagement with Second-Temple expectations of the huios tou anthrōpou, no awareness that “stilling the sea” echoes both Genesis and Exodus motifs of creation and deliverance.

This is scholarship only in the confessional sense of “biblical studies,” where the aim is to explain what discipleship should mean according to current theological norms. It’s homiletics, not analysis.

But my quarrel isn’t really with Oprean. He’s the symptom, not the cause. His paper stands for a broader phenomenon – pseudonymous scholarship: writing that borrows the visual grammar of academic work (citations, subheadings, DOIs, statistical jargon) while serving ideological ends.

You can find parallels across the sciences. In the early 2000s, string theory was on the altar. Articles in Foundations of Physics or in Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics carried the trappings of rigor but were effectively apologias for the “beauty” of untestable theories. “Mathematical consistency,” we were told, “is experimental evidence.” The logic matches Oprean’s: inward coherence replaces external test.

Climate science has its mirror image in policy-driven venues like Energy & Environment or think-tank white papers formatted as peer-reviewed studies. They reproduce the scaffolding of scholarship while narrowing inquiry to confirm prior skepticism.

The rhetorical pattern is the same:

This month’s Sage journal offers a case that makes Oprean look like Richard Feynman. “Dynamic Effect of Green Financing, Economic Development, Renewable Energy and Trade Facilitation on Environmental Sustainability in Developing and Developed Countries” by Usman Ali et al. exhibits the same performative scholarship. The surface polish of method and technical vocabulary hides an absence of real inquiry.

Written in the formal cadence of econometrics – Dynamic Fixed Effects, GEE, co-integration, Sargan tests – it brandishes its methods as credentials rather than arguments. No model specifications, variable definitions, or theoretical tensions appear. “Dynamic” and “robustness” are prestige words, not analytic ones.

Ali’s paper deploys three grand frameworks – Sustainable Development Theory, Innovation Theory, and the Environmental Kuznets Curve – as if piling them together produced insight. But these models conflict! The EKC’s inverted-U relationship between income and pollution is empirically shaky, and no attempt is made to reconcile contradictions. The gesture is interdisciplinary theater: breadth without synthesis.

At least Oprean’s homiletics are harmless. Ali’s conclusion doubles as policy: developed countries must integrate renewables – “science says so.” It’s a sermon in technocratic garb.

Across these domains, and unfortunately many others, we see the creeping genre of methodological theater: environmental-finance papers that treat regressions as theology; equations and robustness tests as icons of faith. The altar may change – from Galilee to global sustainability – but the liturgy is the same.

“The separation of state and church must be complemented by the separation of state and science, that most recent, most aggressive, and most dogmatic religious institution.” Paul Feyerabend, Against Method, 1975

clean energy, energy policy, evangelism, Paul Feyerabend, pseudoscience, religion, science

3 Comments