Posts Tagged History of Science

Grains of Truth: Science and Dietary Salt

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science, Philosophy of Science on June 29, 2025

Science doesn’t proceeds in straight lines. It meanders, collides, and battles over its big ideas. Thomas Kuhn’s view of science as cycles of settled consensus punctuated by disruptive challenges is a great way to understand this messiness, though later approaches, like Imre Lakatos’s structured research programs, Paul Feyerabend’s radical skepticism, and Bruno Latour’s focus on science’s social networks have added their worthwhile spins. This piece takes a light look, using Kuhn’s ideas with nudges from Feyerabend, Lakatos, and Latour, at the ongoing debate over dietary salt, a controversy that’s nuanced and long-lived. I’m not looking for “the truth” about salt, just watching science in real time.

Dietary Salt as a Kuhnian Case Study

The debate over salt’s role in blood pressure shows how science progresses, especially when viewed through the lens of Kuhn’s philosophy. It highlights the dynamics of shifting paradigms, consensus overreach, contrarian challenges, and the nonlinear, iterative path toward knowledge. This case reveals much about how science grapples with uncertainty, methodological complexity, and the interplay between evidence, belief, and rhetoric, even when relatively free from concerns about political and institutional influence.

In The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Kuhn proposed that science advances not steadily but through cycles of “normal science,” where a dominant paradigm shapes inquiry, and periods of crisis that can result in paradigm shifts. The salt–blood pressure debate, though not as dramatic in consequence as Einstein displacing Newton or as ideologically loaded as climate science, exemplifies these principles.

Normal Science and Consensus

Since the 1970s, medical authorities like the World Health Organization and the American Heart Association have endorsed the view that high sodium intake contributes to hypertension and thus increases cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk. This consensus stems from clinical trials such as the 2001 DASH-Sodium study, which demonstrated that reducing salt intake significantly (from 8 grams per day to 4) lowered blood pressure, especially among hypertensive individuals. This, in Kuhn’s view, is the dominant paradigm.

This framework – “less salt means better health” – has guided public health policies, including government dietary guidelines and initiatives like the UK’s salt reduction campaign. In Kuhnian terms, this is “normal science” at work. Researchers operate within an accepted model, refining it with meta-analyses and Randomized Control Trials, seeking data to reinforce it, and treating contradictory findings as anomalies or errors. Public health campaigns, like the AHA’s recommendation of less than 2.3 g/day of sodium, reflect this consensus. Governments’ involvement embodies institutional support.

Anomalies and Contrarian Challenges

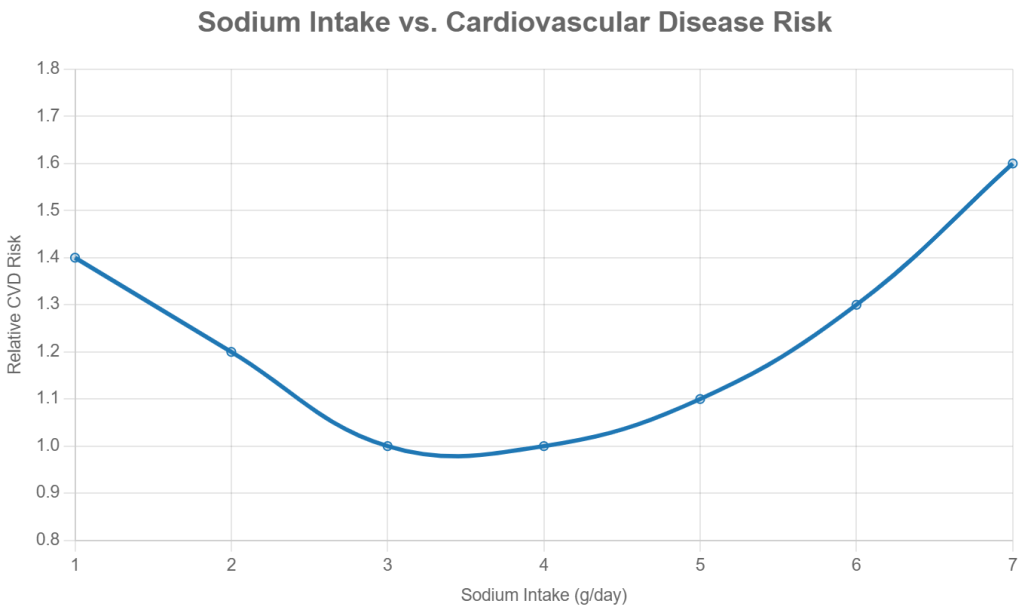

However, anomalies have emerged. For instance, a 2016 study by Mente et al. in The Lancet reported a U-shaped curve; both very low (less than 3 g/day) and very high (more than 5 g/day) sodium intakes appeared to be associated with increased CVD risk. This challenged the linear logic (“less salt, better health”) of the prevailing model. Although the differences in intake were not vast, the implications questioned whether current sodium guidelines were overly restrictive for people with normal blood pressure.

The video Salt & Blood Pressure: How Shady Science Sold America a Lie mirrors Galileo’s rhetorical flair, using provocative language such as “shady science” to challenge the establishment. Like Galileo’s defense of heliocentrism, contrarians in the salt debate (researchers like Mente) amplify anomalies to question dogma, sometimes exaggerating flaws in early studies (e.g., Lewis Dahl’s rat experiments) or alleging conspiracies (e.g., pharmaceutical influence). More in Feyerabend’s view than in Kuhn’s, this exaggeration and rhetoric might be desirable. It’s useful. It provides the challenges that the paradigm should be able to overcome to remain dominant.

These challenges haven’t led to a paradigm shift yet, as the consensus remains robust, supported by RCTs and global health data. But they highlight the Kuhnian tension between entrenched views and emerging evidence, pushing science to refine its understanding.

Framing the issue as a contrarian challenge might go something like this:

Evidence-based medicine sets treatment guidelines, but evidence-based medicine has not translated into evidence-based policy. Governments advise lowering salt intake, but that advice is supported by little robust evidence for the general population. Randomized controlled trials have not strongly supported the benefit of salt reduction for average people. Indeed, we see evidence that low salt might pose as great a risk.

Methodological Challenges

The question “Is salt bad for you?” is ill-posed. Evidence and reasoning say this question oversimplifies a complex issue: sodium’s effects vary by individual (e.g., salt sensitivity, genetics), diet (e.g., processed vs. whole foods), and context (e.g., baseline blood pressure, activity level). Science doesn’t deliver binary truths. Modern science gives probabilistic models, refined through iterative testing.

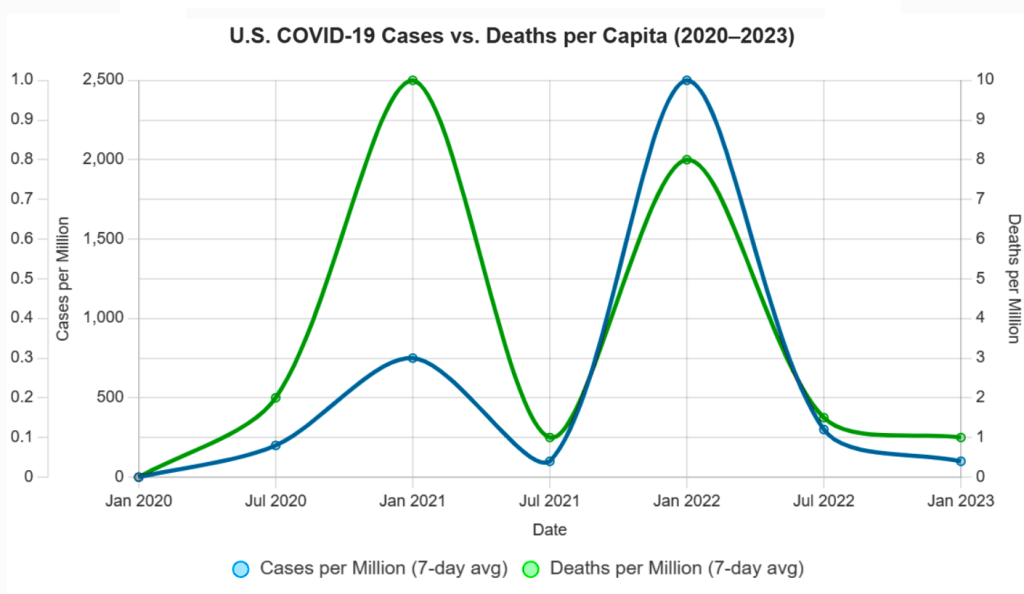

While randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have shown that reducing sodium intake can lower blood pressure, especially in sensitive groups, observational studies show that extremely low sodium is associated with poor health. This association may signal reverse causality, an error in reasoning. The data may simply reveal that sicker people eat less, not that they are harmed by low salt. This complexity reflects the limitations of study design and the challenges of isolating causal relationships in real-world populations. The above graph is a fairly typical dose-response curve for any nutrient.

The salt debate also underscores the inherent difficulty of studying diet and health. Total caloric intake, physical activity, genetic variation, and compliance all confound the relationship between sodium and health outcomes. Few studies look at salt intake as a fraction of body weight. If sodium recommendations were expressed as sodium density (mg/kcal), it might help accommodate individual energy needs and eating patterns more effectively.

Science as an Iterative Process

Despite flaws in early studies and the polemics of dissenters, the scientific communities continue to refine its understanding. For example, Japan’s national sodium reduction efforts since the 1970s have coincided with significant declines in stroke mortality, suggesting real-world benefits to moderation, even if the exact causal mechanisms remain complex.

Through a Kuhnian lens, we see a dominant paradigm shaped by institutional consensus and refined by accumulating evidence. But we also see the system’s limits: anomalies, confounding variables, and methodological disputes that resist easy resolution.

Contrarians, though sometimes rhetorically provocative or methodologically uneven, play a crucial role. Like the “puzzle-solvers” and “revolutionaries” in Kuhn’s model, they pressure the scientific establishment to reexamine assumptions and tighten methods. This isn’t a flaw in science; it’s the process at work.

Salt isn’t simply “good” or “bad.” The better scientific question is more conditional: How does salt affect different individuals, in which contexts, and through what mechanisms? Answering this requires humility, robust methodology, and the acceptance that progress usually comes in increments. Science moves forward not despite uncertainty, disputation and contradiction but because of them.

After the Applause: Heilbron Rereads Feyerabend

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science, Philosophy of Science on June 4, 2025

A decade ago, in a Science, Technology and Society (STS) roundtable, I brought up Paul Feyerabend, who was certainly familiar to everyone present. I said that his demand for a separation of science and state – his call to keep science from becoming a tool of political authority – seemed newly relevant in the age of climate science and policy entanglement. Before I could finish the thought, someone cut in: “You can’t use Feyerabend to support republicanism!”

I hadn’t made an argument. Feyerabend was being claimed as someone who belonged to one side of a cultural war. His ideas were secondary. That moment stuck with me, not because I was misunderstood, but because Feyerabend was. And maybe he would have loved that. He was ambiguous by design. The trouble is that his deliberate opacity has hardened, over time, into distortion.

Feyerabend survives in fragments and footnotes. He’s the folk hero who overturned Method and danced on its ruins. He’s a cautionary tale: the man who gave license to science denial, epistemic relativism, and rhetorical chaos. You’ll find him invoked in cultural studies and critiques of scientific rationality, often with little more than the phrase “anything goes” as evidence. He’s also been called “the worst enemy of science.”

Against Method is remembered – or reviled – as a manifesto for intellectual anarchy. But “manifesto” doesn’t fit at all. It didn’t offer a vision, a list of principles, or a path forward. It has no normative component. It offered something stranger: a performance.

Feyerabend warned readers in the preface that the book would contradict itself, that it wasn’t impartial, and that it was meant to persuade, not instruct. He said – plainly and explicitly – that later parts would refute earlier ones. It was, in his words, a “tendentious” argument. And yet neither its admirers nor its critics have taken that warning seriously.

Against Method has become a kind of Rorschach test. For some, it’s license; for others, sabotage. Few ask what Feyerabend was really doing – or why he chose that method to attack Method. A few of us have long argued that Against Method has been misread. It was never meant as a guidebook or a threat, but as a theatrical critique staged to provoke and destabilize something that badly needed destabilizing.

That, I was pleased to learn, is also the argument made quietly and precisely in the last published work of historian John Heilbron. It may be the most honest reading of Feyerabend we’ve ever had.

John once told me that, unlike Kuhn, he had “the metabolism of a historian,” a phrase that struck me later as a perfect self-diagnosis: patient, skeptical, and slow-burning. He’d been at Berkeley when Feyerabend was still strutting the halls in full flair – the accent, the dramatic pronouncements, the partying. John didn’t much like him. He said so over lunch, on walks, at his house or mine. Feyerabend was hungry for applause, and John disapproved of his personal appetites and the way he flaunted them.

And yet… John’s recent piece on Feyerabend – the last thing he ever published – is microscopically delicate, charitable, and clear-eyed. John’s final chapter in Stefano Gattei’s recent book, Feyerabend in Dialogue, contains no score-settling, no demolition. Just a forensic mind trained to separate signal from noise. If Against Method is a performance, Heilbron doesn’t boo it offstage. He watches it again, closely, and tells us how it was done. Feyerabend through Heilbron’s lens is a performance reframed.

If anyone was positioned to make sense of Feyerabend, rhetorically, philosophically, and historically, it was Heilbron – Thomas Kuhn’s first graduate student, a lifelong physicist-turned-historian, and an expert on both early modern science and quantum theory’s conceptual tangles. His work on Galileo, Bohr, and the Scientific Revolution was always precise, occasionally sly, and never impressed by performance for performance’s sake.

That care is clearest in his treatment of Against Method’s most famous figure: Galileo. Feyerabend made Galileo the centerpiece of his case against scientific method – not as a heroic rationalist, but as a cunning rhetorician who won not because of superior evidence, but because of superior style. He compared Galileo to Goebbels, provocatively, to underscore how persuasion, not demonstration, drove the acceptance of heliocentrism. In Feyerabend’s hands, Galileo became a theatrical figure, a counterweight to the myth of Enlightenment rationality.

Heilbron dismantles this with the precision of someone who has lived in Galileo’s archives. He shows that while Galileo lacked a modern theory of optics, he was not blind to his telescope’s limits. He cross-checked, tested, and refined. He triangulated with terrestrial experiments. He understood that instruments could deceive, and worked around that risk with repetition and caution. The image of Galileo as a showman peddling illusions doesn’t hold up. Galileo, flaws acknowledged, was a working proto-scientist, attentive to the fragility of his tools.

Heilbron doesn’t mythologize Galileo; his 2010 Galileo makes that clear. But he rescues Galileo from Feyerabend’s caricature. In doing so, he models something Against Method never offered: a historically grounded, philosophically rigorous account of how science proceeds when tools are new, ideas unstable, and theory underdetermined by data.

To be clear, Galileo was no model of transparency. He framed the Dialogue as a contest between Copernicus and Ptolemy, though he knew Tycho Brahe’s hybrid system was the more serious rival. He pushed his theory of tides past what his evidence could support, ignoring counterarguments – even from Cardinal Bellarmine – and overstating the case for Earth’s motion.

Heilbron doesn’t conceal these. He details them, but not to dismiss. For him, these distortions are strategic flourishes – acts of navigation by someone operating at the edge of available proof. They’re rhetorical, yes, but grounded in observation, subject to revision, and paid for in methodological care.

That’s where the contrast with Feyerabend sharpens. Feyerabend used Galileo not to advance science, but to challenge its authority. More precisely, to challenge Method as the defining feature of science. His distortions – minimizing Galileo’s caution, questioning the telescope, reimagining inquiry as theater – were made not in pursuit of understanding, but in service of a larger philosophical provocation. This is the line Heilbron quietly draws: Galileo bent the rules to make a case about nature; Feyerabend bent the past to make a case about method.

In his final article, Heilbron makes four points. First, that the Galileo material in Against Method – its argumentative keystone – is historically slippery and intellectually inaccurate. Feyerabend downplays empirical discipline and treats rhetorical flourish as deception. Heilbron doesn’t call this dishonest. He calls it stagecraft.

Second, that Feyerabend’s grasp of classical mechanics, optics, and early astronomy was patchy. His critique of Galileo’s telescope rests on anachronistic assumptions about what Galileo “should have” known. He misses the trial-based, improvisational reasoning of early instrumental science. Heilbron restores that context.

Third, Heilbron credits Feyerabend’s early engagement with quantum mechanics – especially his critique of von Neumann’s no-hidden-variables proof and his alignment with David Bohm’s deterministic alternative. Feyerabend’s philosophical instincts were sharp.

And fourth, Heilbron tracks how Feyerabend’s stance unraveled – oscillating between admiration and disdain for Popper, Bohr, and even his earlier selves. He supported Bohm against Bohr in the 1950s, then defended Bohr against Popper in the 1970s. Heilbron doesn’t call this hypocrisy. He calls it instability built into the project itself: Feyerabend didn’t just critique rationalism – he acted out its undoing. If this sounds like a takedown, it isn’t. It’s a reconstruction – calm, slow, impartial. The rare sort that shows us not just what Feyerabend said, but where he came apart.

Heilbron reminds us what some have forgotten and many more never knew: that Feyerabend was once an insider. Before Against Method, he was embedded in the conceptual heart of quantum theory. He studied Bohm’s challenge to Copenhagen while at LSE, helped organize the 1957 Colston symposium in Bristol, and presented a paper there on quantum measurement theory. He stood among physicists of consequence – Bohr, Bohm, Podolsky, Rosen, Dirac, and Pauli – all struggling to articulate alternatives to an orthodoxy – Copenhagen Interpretation – that they found inadequate.

With typical wit, Heilbron notes that von Neumann’s no-hidden-variables proof “was widely believed, even by people who had read it.” Feyerabend saw that dogma was hiding inside the math – and tried to smoke it out.

Late in life, Feyerabend’s provocations would ripple outward in unexpected directions. In a 1990 lecture at Sapienza University, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger – later Pope Benedict XVI – quoted Against Method approvingly. He cited Feyerabend’s claim that the Church had been more reasonable than Galileo in the affair that defined their rupture. When Ratzinger’s 2008 return visit was canceled due to protests about that quotation, the irony was hard to miss. The Church, once accused of silencing science, was being silenced by it, and stood accused of quoting a philosopher who spent his life telling scientists to stop pretending they were priests.

We misunderstood Feyerabend not because he misled us, but because we failed to listen the way Heilbron did.

Anarchy and Its Discontents: Paul Feyerabend’s Critics

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science, Philosophy of Science on June 3, 2025

(For and against Against Method)

Paul Feyerabend’s 1975 Against Method and his related works made bold claims about the history of science, particularly the Galileo affair. He argued that science progressed not because of adherence to any specific method, but through what he called epistemological anarchism. He said that Galileo’s success was due in part to rhetoric, metaphor, and politics, not just evidence.

Some critics, especially physicists and historically rigorous philosophers of science, have pointed out technical and historical inaccuracies in Feyerabend’s treatment of physics. Here are some examples of the alleged errors and distortions:

Misunderstanding Inertial Frames in Galileo’s Defense of Copernicanism

Feyerabend argued that Galileo’s arguments for heliocentrism were not based on superior empirical evidence, and that Galileo used rhetorical tricks to win support. He claimed that Galileo simply lacked any means of distinguishing heliocentric from geocentric models empirically, so his arguments were no more rational than those of Tycho Brahe and other opponents.

His critics responded by saying that Galileo’s arguments based on the phases of Venus and Jupiter’s moons were empirically decisive against the Ptolemaic model. This is unarguable, though whether Galileo had empirical evidence to overthrow Tycho Brahe’s hybrid model is a much more nuanced matter.

Critics like Ronald Giere, John Worrall, and Alan Chalmers (What Is This Thing Called Science?) argued that Feyerabend underplayed how strong Galileo’s observational case actually was. They say Feyerabend confused the issue of whether Galileo had a conclusive argument with whether he had a better argument.

This warrants some unpacking. Specifically, what makes an argument – a model, a theory – better? Criteria might include:

- Empirical adequacy – Does the theory fit the data? (Bas van Fraassen)

- Simplicity – Does the theory avoid unnecessary complexity? (Carl Hempel)

- Coherence – Is it internally consistent? (Paul Thagard)

- Explanatory power – Does it explain more than rival theories? (Wesley Salmon)

- Predictive power – Does it generate testable predictions? (Karl Popper, Hempel)

- Fertility – Does it open new lines of research? (Lakatos)

Some argue that Galileo’s model (Copernicanism, heliocentrism) was obviously simpler than Brahe’s. But simplicity opens another can of philosophical worms. What counts as simple? Fewer entities? Fewer laws? More symmetry? Copernicus had simpler planetary order but required a moving Earth. And Copernicus still relied on epicycles, so heliocentrism wasn’t empirically simpler at first. Given the evidence of the time, a static Earth can be seen as simpler; you don’t need to explain the lack of wind and the “straight” path of falling bodies. Ultimately, this point boils down to aesthetics, not math or science. Galileo and later Newtonians valued mathematical elegance and unification. Aristotelians, the church, and Tychonians valued intuitive compatibility with observed motion.

Feyerabend also downplayed Galileo’s use of the principle of inertia, which was a major theoretical advance and central to explaining why we don’t feel the Earth’s motion.

Misuse of Optical Theory in the Case of Galileo’s Telescope

Feyerabend argued that Galileo’s use of the telescope was suspect because Galileo had no good optical theory and thus no firm epistemic ground for trusting what he saw.

His critics say that while Galileo didn’t have a fully developed geometrical optics theory (e.g., no wave theory of light), his empirical testing and calibration of the telescope were rigorous by the standards of the time.

Feyerabend is accused of anachronism – judging Galileo’s knowledge of optics by modern standards and therefore misrepresenting the robustness of his observational claims. Historians like Mario Biagioli and Stillman Drake point out that Galileo cross-verified telescope observations with the naked eye and used repetition, triangulation, and replication by others to build credibility.

Equating All Theories as Rhetorical Equals

Feyerabend in some parts of Against Method claimed that rival theories in the history of science were only judged superior in retrospect, and that even “inferior” theories like astrology or Aristotelian cosmology had equal rational footing at the time.

Historians like Steven Shapin (How to be Antiscientific) and David Wootton (The Invention of Science) say that this relativism erases real differences in how theories were judged even in Galileo’s time. While not elaborated in today’s language, Galileo and his rivals clearly saw predictive power, coherence, and observational support as fundamental criteria for choosing between theories.

Feyerabend’s polemical, theatrical tone often flattened the epistemic distinctions that working scientists and philosophers actually used, especially during the Scientific Revolution. His analysis of “anything goes” often ignored the actual disciplinary practices of science, especially in physics.

Failure to Grasp the Mathematical Structure of Physics

Scientists – those broad enough to know who Feyerabend was – often claim that he misunderstood or ignored the role of mathematics in theory-building, especially in Newtonian mechanics and post-Galilean developments. In Against Method, Feyerabend emphasizes metaphor and persuasion over mathematics. While this critique is valuable when aimed at the rhetorical and political sides of science, it underrates the internal mathematical constraints that shape physical theories, even for Galileo.

Imre Lakatos, his friend and critic, called Feyerabend’s work a form of “intellectual sabotage”, arguing that he distorted both the history and logic of physics.

Misrepresenting Quantum Mechanics

Feyerabend wrote about Bohr and Heisenberg in Philosophical Papers and later essays. Critics like Abner Shimony and Mario Bunge charge that Feyerabend misrepresented or misunderstood Bohr’s complementarity as relativistic, when Bohr’s position was more subtle and aimed at objective constraints on language and measurement.

Feyerabend certainly fails to understand the mathematical formalism underpinning Quantum Mechanics. This weakens his broader claims about theory incommensurability.

Feyerabend’s erroneous critique of Neil’s Bohr is seen in his 1958 Complimentarity:

“Bohr’s point of view may be introduced by saying that it is the exact opposite of [realism]. For Bohr the dual aspect of light and matter is not the deplorable consequence of the absence of a satisfactory theory, but a fundamental feature of the microscopic level. For him the existence of this feature indicates that we have to revise … the [realist] ideal of explanation.” (more on this in an upcoming post)

Epistemic Complaints

Beyond criticisms that he failed to grasp the relevant math and science, Feyerabend is accused of selectively reading or distorting historical episodes to fit the broader rhetorical point that science advances by breaking rules, and that no consistent method governs progress. Feyerabend’s claim that in science “anything goes” can be seen as epistemic relativism, leaving no rational basis to prefer one theory over another or to prefer science over astrology, myth, or pseudoscience.

Critics say Feyerabend blurred the distinction between how theories are argued (rhetoric) and how they are justified (epistemology). He is accused of conflating persuasive strategy with epistemic strength, thereby undermining the very principle of rational theory choice.

Some take this criticism to imply that methodological norms are the sole basis for theory choice. Feyerabend’s “anarchism” may demolish authority, but is anything left in its place except a vague appeal to democratic or cultural pluralism? Norman Levitt and Paul Gross, especially in Higher Superstition: The Academic Left and Its Quarrels with Science (1994), argue this point, along with saying Feyerabend attacked a caricature of science.

Personal note/commentary: In my view, Levitt and Gross did some great work, but Higher Superstition isn’t it. I bought the book shortly after its release because I was disgusted with weaponized academic anti-rationalism, postmodernism, relativism, and anti-science tendencies in the humanities, especially those that claimed to be scientific. I was sympathetic to Higher Superstition’s mission but, on reading it, was put off by its oversimplifications and lack of philosophical depth. Their arguments weren’t much better than those of the postmodernists. Critics of science in the humanities critics overreached and argued poorly, but they were responding to legitimate concerns in the philosophy of science. Specifically:

- Underdetermination – Two incompatible theories often fit the same data. Why do scientists prefer one over another? As Kuhn argued, social dynamics play a role.

- Theory-laden Observations – Observations are shaped by prior theory and assumptions, so science is not just “reading the book of nature.”

- Value-laden Theories – Public health metrics like life expectancy and morbidity (opposed to autonomy or quality of life) trickle into epidemiology.

- Historical Variability of Consensus – What’s considered rational or obvious changes over time (phlogiston, luminiferous ether, miasma theory).

- Institutional Interest and Incentives – String theory’s share of limited research funding, climate science in service of energy policy and social agenda.

- The Problem of Reification – IQ as a measure of intelligence has been reified in policy and education, despite deep theoretical and methodological debates about what it measures.

- Political or Ideological Capture – Marxist-Leninist science and eugenics were cases where ideology shaped what counted as science.

Higher Superstition and my unexpected negative reaction to it are what brought me to the discipline of History and Philosophy of Science.

Conclusion

Feyerabend exaggerated the uncertainty of early modern science, downplayed the empirical gains Galileo and others made, and misrepresented or misunderstood some of the technical content of physics. His mischievous rhetorical style made it hard to tell where serious argument ended and performance began. Rather than offering a coherent alternative methodology, Feyerabend’s value lay in exposing the fragility and contingency of scientific norms. He made it harder to treat methodological rules as timeless or universal by showing how easily they fracture under the pressure of real historical cases.

In a following post, I’ll review the last piece John Heilbron wrote before he died, Feyerabend, Bohr and Quantum Physics, which appeared in Stefano Gattei’s Feyerabend in Dialogue, a set of essays marking the 100th anniversary of Feyerabend’s birth.

Paul Feyerabend. Photo courtesy of Grazia Borrini-Feyerabend.

John Heilbron Interview – June 2012

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science, Philosophy of Science on June 2, 2025

In 2012, I spoke with John Heilbron, historian of science and Professor Emeritus at UC Berkeley, about his career, his work with Thomas Kuhn, and the legacy of The Structure of Scientific Revolutions on its 50th anniversary. We talked late into the night. The conversation covered his shift from physics to history, his encounters with Kuhn and Paul Feyerabend, and his critical take on the direction of Science and Technology Studies (STS).

The interview marked a key moment. Kuhn and Feyerabend’s legacies were under fresh scrutiny, and STS was in the midst of redefining itself, often leaning toward sociological frameworks at the expense of other approaches.

Thirteen years later, in 2025, this commentary revisits that interview to illuminate its historical context, situate Heilbron’s critiques, and explore their relevance to contemporary STS and broader academic debates.

Over more than a decade, I had ongoing conversations with Heilbron about the evolution of the history of science – history of the history of science – and the complex relationship between History of Science and Science, Technology, and Society (STS) programs. At UC Berkeley, unlike at Harvard or Stanford, STS has long remained a “Designated Emphasis” rather than a department or standalone degree. Academic conservatism in departmental structuring, concerns about reputational risk, and questions about the epistemic rigor of STS may all have contributed to this decision. Moreover, Berkeley already boasted world-class departments in both History and Sociology.

That 2012 interview, the only one we recorded, brought together themes we’d explored over many years. Since then, STS has moved closer to engaging with scientific content itself. But it still draws criticism, both from scientists and from public misunderstanding. In 2012, the field was still heavily influenced by sociological models, particularly the Strong Programme and social constructivism, which stressed how scientific knowledge is shaped by social context. One of the key texts in this tradition, Shapin and Schaffer’s Leviathan and the Air-Pump (1985), argued that even Boyle’s experiments weren’t simply about discovery but about constructing scientific consensus.

Heilbron pushed back against this framing. He believed it sidelined the technical and epistemic depth of science, reducing STS to a sociological critique. He was especially wary of the dense, abstract language common in constructivist work. In his view, it often served as cover for thin arguments, especially from younger scholars who copied the style but not the substance. He saw it as a tactic: establish control of the conversation by embedding a set of terms, then build influence from there.

The influence of Shapin and Schaffer, Heilbron argued, created the impression that STS was dominated by a single paradigm, ironically echoing the very Kuhnian framework they analyzed. His frustration with a then-recent Isis review reflected his concern that constructivism had become doctrinaire, pressuring scholars to conform to its methods even when irrelevant to their work. His reference to “political astuteness” pointed to the way in which key figures in the field successfully advanced their terminology and frameworks, gaining disproportionate influence. While this gave them intellectual clout, Heilbron saw it as a double-edged sword: it strengthened their position while encouraging dogmatism among followers who prioritized jargon over genuine analysis.

Bill Storage: How did you get started in this curious interdisciplinary academic realm?

John Heilbron: Well, it’s not really very interesting, but I was a graduate student in physics but my real interest was history. So at some point I went down to the History department and found the medievalist, because I wanted to do medieval history. I spoke with the medievalist ad he said, “well, that’s very charming but you know the country needs physicists and it doesn’t need medievalists, so why don’t you go back to physics.” Which I duly did. But he didn’t bother to point out that there was this guy Kuhn in the History department who had an entirely different take on the subject than he did. So finally I learned about Kuhn and went to see him. Since Kuhn had very few students, I looked good; and I gradually I worked my way free from the Physics department and went into history. My PhD is in History; and I took a lot history courses and, as I said, history really is my interest. I’m interested in science too of course but I feel that my major concerns are historical and the writing of history is to me much more interesting and pleasant than calculations.

You entered that world at a fascinating time, when history of science – I’m sure to the surprise of most of its scholars – exploded onto the popular scene. Kuhn, Popper, Feyerabend and Lakatos suddenly appeared in The New Yorker, Life Magazine, and The Christian Century. I find that these guys are still being read, misread and misunderstood by many audiences. And that seems to be true even for their intended audiences – sometimes by philosophers and historians of science – certainly by scientists. I see multiple conflicting readings that would seem to show that at least some of them are wrong.

Well if you have two or more different readings then I guess that’s a safe conclusion. (Laughs.)

You have a problem with multiple conflicting truths…? Anyway – misreading Kuhn…

I’m more familiar with the misreading of Kuhn than of the others. I’m familiar with that because he was himself very distressed by many of the uses made of his work – particularly the notion that science is no different from art or has no stronger basis than opinion. And that bothered him a lot.

I don’t know your involvement in his work around that time. Can you tell me how you relate to what he was doing in that era?

I got my PhD under him. In fact my first work with him was hunting up footnotes for Structure. So I knew the text of the final draft well – and I knew him quite well during the initial reception of it. And then we all went off together to Copenhagen for a physics project and we were all thrown together a lot. So that was my personal connection and then of course I’ve been interested subsequently in Structure, as everybody is bound to be in my line of work. So there’s no doubt, as he says so in several places, that he was distressed by the uses made of it. And that includes uses made in the history of science particularly by the social constructionists, who try to do without science altogether or rather just to make it epiphenomenal on political or social forces.

I’ve read opinions by others who were connected with Kuhn saying there was a degree of back-peddling going by Kuhn in the 1970s. The implication there is that he really did intend more sociological commentary than he later claimed. Now I don’t see evidence of that in the text of Structure, and incidents like his telling Freeman Dyson that he (Kuhn) was not a Kuhnian would suggest otherwise. Do you have any thoughts on that?

I think that one should keep in mind the purpose of Structure, or rather the context in which it was produced. It was supposed to have been an article in this encyclopedia of unified science and Kuhn’s main interest was in correcting philosophers. He was not aiming for historians even. His message was that the philosophy practiced by a lot of positivists and their description of science was ridiculous because it didn’t pay any attention to the way science was actually done. So Kuhn was going to tell them how science was done, in order to correct philosophy. But then much to his surprise he got picked up by people for whom it was not written, who derived from it the social constructionist lesson that we’re all familiar with. And that’s why he was an unexpected rebel. But he did expect to be rebellious; that was the whole point. It’s just that the object of his rebellion was not history or science but philosophy.

So in that sense it would seem that Feyerabend’s question on whether Kuhn intended to be prescriptive versus descriptive is answered. It was not prescriptive.

Right – not prescriptive to scientists. But it was meant to be prescriptive to the philosophers – or at least normalizing – so that they would stop being silly and would base their conception of scientific progress on the way in which scientists actually went about their business. But then the whole thing got too big for him and he got into things that, in my opinion, really don’t have anything to do with his main argument. For example, the notion of incommensurability, which was not, it seems to me, in the original program. And it’s a logical construct that I don’t think is really very helpful, and he got quite hung up on that and seemed to regard that as the most important philosophical message from Structure.

I wasn’t aware that he saw it that way. I’m aware that quite a few others viewed it like that. Paul Feyerabend, in one of his last books, said that he and Kuhn kicked around this idea of commensurability in 1960 and had slightly different ideas about where to go with it. Feyerabend said Kuhn wanted to use it historically whereas his usage was much more abstract. I was surprised at the level of collaboration indicated by Feyerabend.

Well they talked a lot. They were colleagues. I remember parties at Kuhn’s house where Feyerabend would show up with his old white T shirt and several women – but that’s perhaps irrelevant to the main discussion. They were good friends. I got along quite well with Feyerabend too. We had discussions about the history of quantum physics and so on. The published correspondence between Feyerabend and Lakatos is relevant here. It’s rather interesting in that the person we’ve left out of the discussion so far, Karl Popper, was really the lighthouse for Feyerabend and Lakatos, but not for Kuhn. And I think that anybody who wants to get to the bottom of the relationship between Kuhn and Feyerabend needs to consider the guy out of the frame, who is Popper.

It appears Feyerabend was very critical of Kuhn and Structure at the time it was published. I think at that point Feyerabend was still essentially a Popperian. It seems Feyerabend reversed position on that over the next decade or so.

JH: Yes, at the time in question, around 1960, when they had these discussions, I think Feyerabend was still very much in Popper’s camp. Of course like any bright student, he disagreed with his professor about things.

How about you, as a bright student in 1960 – what did you disagree with your professor, Kuhn, about?

Well I believe in the proposition that philosophers and historians have different metabolisms. And I’m metabolically a historian and Kuhn was metabolically a philosopher – even though he did write history. But his most sustained piece of history of science was his book on black body theory; and that’s very narrowly intellectualist in approach. It’s got nothing to do with the themes of the structure of scientific revolutions – which does have something to say for the historian – but he was not by practice a historian. He didn’t like a whole lot of contingent facts. He didn’t like archival and library work. His notion of fun was take a few texts and just analyze and reanalyze them until he felt he had worked his way into the mind of their author. I take that to be a necromantic feat that’s not really possible.

I found that he was a very clever guy and he was excellent as a professor because he was very interested in what you were doing as soon it was something he thought he could make some use of. And that gave you the idea that you were engaged in something important, so I must give him that. On the other hand he just didn’t have the instincts or the knowledge to be a historian and so I found myself not taking much from his own examples. Once I had an argument with him about some way of treating a historical subject and I didn’t feel that I got anything out of him. Quite the contrary; I thought that he just ducked all the interesting issues. But that was because they didn’t concern him.

James Conant, president of Harvard who banned communists, chair of the National Science Foundation, etc.: how about Conant’s influence on Structure?

It’s not just Conant. It was the whole Harvard circle, of which Kuhn was part. There was this guy, Leonard Nash; there was Gerald Holton. And these guys would get together and l talk about various things having to do with the relationship between science and the public sphere. It was a time when Conant was fighting for the National Science Foundation and I think that this notion of “normal science” in which the scientists themselves must be left fully in charge of what they’re doing in order to maximize the progress within the paradigm to bring the profession swiftly to the next revolution – that this is essentially the Conant doctrine with respect to the ground rules of the National Science Foundation, which is “let the scientists run it.” So all those things were discussed. And you can find many bits of Kuhn’s Structure in that discussion. For example, the orthodoxy of normal science in, say, Bernard Cohen, who didn’t make anything of it of course. So there’s a lot of this Harvard group in Structure, as well as certain lessons that Kuhn took from his book on the Copernican Revolution, which was the textbook for the course he gave under Conant. So yes, I think Conant’s influence is very strong there.

So Kuhn was ultimately a philosopher where you are a historian. I think I once heard you say that reading historical documents does not give you history.

Well I agree with that, but I don’t remember that I was clever enough to say it.

Assuming you said it or believe it, then what does give you history?

Well, reading them is essential, but the part contributed by the historian is to make some sense of all the waste paper he’s been reading. This is essentially a construction. And that’s where the art, the science, the technique of the historian comes into play, to try to make a plausible narrative that has to satisfy certain rules. It can’t go against the known facts and it can’t ignore the new facts that have come to light through the study of this waste paper, and it can’t violate rules of verisimilitude, human action and whatnot. But otherwise it’s a construction and you’re free to manipulate your characters, and that’s what I like about it.

So I take it that’s where the historian’s metabolism comes into play – avoidance of leaping to conclusions with the facts.

True, but at some point you’ve got to make up a story about those facts.

Ok, I’ve got a couple questions on the present state of affairs – and this is still related to the aftermath of Kuhn. From attending colloquia, I sense that STS is nearly a euphemism for sociology of science. That bothers me a bit, possibly because I’m interested in the intersection of science, technology and society. Looking at the core STS requirements on Stanford’s website, I see few courses listed that would give a student any hint of what science looks like from the inside.

I’m afraid you’re only too right. I’ve got nothing against sociology of science, the study of scientific institutions, etc. They’re all very good. But they’re tending to leave the science out, and in my opinion, the further they get from science, the worse their arguments become. That’s what bothers me perhaps most of all – the weakness of the evidentiary base of many of the arguments and conclusions that are put forward.

I thought we all learned a bit from the Science Wars – thought that sort of indeterminacy of meaning and obfuscatory language was behind us. Either it’s back, or it never went away.

Yeah, the language part is an important aspect of it, and even when the language is relatively comprehensible as I think it is in, say, constructivist history of science – by which I mean the school of Schaffer and Shapin – the insistence on peculiar argot becomes a substitute for thought. You see it quite frequently in people less able than those two guys are, who try to follow in their footsteps. You get words strung together supposedly constituting an argument but which in fact don’t. I find that quite an interesting aspect of the business, and very astute politically on the part of those guys because if you can get your words into the discourse, why, you can still hope to have influence. There’s a doctrinaire aspect to it. I was just reading the current ISIS favorable book review by one of the fellow travelers of this group. The book was not written by one of them. The review was rather complimentary but then at the end says it is a shame that this author did not discuss her views as related to Schaffer and Shapin. Well, why the devil should she? So, yes, there’s issues of language, authority, and poor argumentation. STS is afflicted by this, no doubt.

Bad Science, Broken Trust: Commentary on Pandemic Failure

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science on May 20, 2025

In my three previous posts (1, 2, 3) on the Covid-19 response and statistical reasoning, I deliberately sidestepped a deeper, more uncomfortable truth that emerges from such analysis: that ideologically driven academic and institutional experts – credentialed, celebrated, and deeply embedded in systems of authority – played a central role in promoting flawed statistical narratives that served political agendas and personal advancement. Having defended my claims in two previous posts – from the perspective of a historian of science – I now feel I justified in letting it rip. Bad science, bad statistics, and institutional arrogance directly shaped a public health disaster.

What we witnessed was not just error, but hubris weaponized by institutions. Self-serving ideologues – cloaked in the language of science – shaped policies that led, in no small part, to hundreds of thousands of preventable deaths. This was not a failure of data, but of science and integrity, and it demands a historical reckoning.

The Covid-19 pandemic exacted a devastating toll: a 13% global GDP collapse in Q2 2020, and a 12–15% spike in adolescent suicidal ideation, as reported by Nature Human Behaviour (2020) and JAMA Pediatrics (2021). These catastrophic outcomes –economic freefall and a mental health crisis – can’t be blamed on the pathogen. Its lethality was magnified by avoidable policy blunders rooted in statistical incompetence and institutional cowardice. Five years on, the silence from public health authorities is deafening. The opportunity to learn from these failures – and to prevent their repetition – is being squandered before our eyes.

One of the most glaring missteps was the uncritical use of raw case counts to steer public policy – a volatile metric, heavily distorted by shifting testing rates, as The Lancet (2021, cited earlier) highlighted. More robust measures like deaths per capita or infection fatality rates, advocated by Ioannidis (2020), were sidelined, seemingly for facile politics. The result: fear-driven lockdowns based on ephemeral, tangential data. The infamous “6-foot rule,” based on outdated droplet models, continued to dominate public messaging through 2020 and beyond – even though evidence (e.g., BMJ, 2021) solidly pointed to airborne transmission. This refusal to pivot toward reality delayed life-saving ventilation reforms and needlessly prolonged school closures, economic shutdowns, and the cascading psychological harm they inflicted.

At the risk of veering into anecdote, this example should not be lost to history: In 2020, a surfer was arrested off Malibu Beach and charged with violating the state’s stay-at-home order. As if he might catch or transmit Covid – alone, in the open air, on the windswept Pacific. No individual could possibly believe that posed a threat. It takes a society – its institutions, its culture, its politics – to manufacture collective stupidity on that scale.

The consequences of these reasoning failures were grave. And yet, astonishingly, there has been no comprehensive, transparent institutional reckoning. No systematic audits. No revised models. No meaningful reforms from the CDC, WHO, or major national agencies. Instead, we see a retrenchment: the same narratives, the same faces, and the same smug complacency. The refusal to account for aerosol dynamics, mental health trade-offs, or real-time data continues to compromise our preparedness for future crises. This is not just negligence. It is a betrayal of public trust.

If the past is not confronted, it will be repeated. We can’t afford another round of data-blind panic, policy overreach, and avoidable harm. What’s needed now is not just reflection but action: independent audits of pandemic responses, recalibrated risk models that incorporate full-spectrum health and social impacts, and a ruthless commitment to sound use of data over doctrine.

The suffering of 2020–2022 must mean something. If we want resilience next time, we must demand accountability this time. The era of unexamined expert authority must end – not to reject expertise – but to restore it to a foundation of integrity, humility, and empirical rigor.

It’s time to stop forgetting – and start building a public health framework worthy of the public it is supposed to serve.

___ ___ ___

Covid Response – Case Counts and Failures of Statistical Reasoning

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science on May 19, 2025

In my previous post I defended three claims made in an earlier post about relative successes in statistics and statistical reasoning in the American Covid-19 response. This post gives support for three claims regarding misuse of statistics and poor statistical reasoning during the pandemic.

Misinterpretation of Test Results (4)

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, many clinicians and media figures misunderstood diagnostic test accuracy, misreading PCR and antigen test results by overlooking pre-test probability. This caused false reassurance or unwarranted alarm, though some experts mitigated errors with Bayesian reasoning. This was precisely the type of mistake highlighted in the Harvard study decades earlier. (4)

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests, while considered the gold standard for detecting SARS-CoV-2, were known to have variable sensitivity (70–90%) depending on factors like sample quality, timing of testing relative to infection, and viral load. False negatives were a significant concern, particularly when clinicians or media interpreted a negative result as definitively ruling out infection without considering pre-test probability (the likelihood of disease based on symptoms, exposure, or prevalence). Similarly, antigen tests, which are less sensitive than PCR, were prone to false negatives, especially in low-prevalence settings or early/late stages of infection.

A 2020 article in Journal of General Internal Medicine noted that physicians often placed undue confidence in test results, minimizing clinical reasoning (e.g., pre-test probability) and deferring to imperfect tests. This was particularly problematic for PCR false negatives, which could lead to a false sense of security about infectivity.

A 2020 Nature Reviews Microbiology article reported that during the early pandemic, the rapid development of diagnostic tests led to implementation challenges, including misinterpretation of results due to insufficient consideration of pre-test probability. This was compounded by the lack of clinical validation for many tests at the time.

Media reports often oversimplified test results, presenting PCR or antigen tests as definitive without discussing limitations like sensitivity, specificity, or the role of pre-test probability. Even medical professionals struggled with Bayesian reasoning, leading to public confusion about test reliability.

Antigen tests, such as lateral flow tests, were less sensitive than PCR (pooled sensitivity of 64.2% in pediatric populations) but highly specific (99.1%). Their performance varied significantly with pre-test probability, yet early in the pandemic, they were sometimes used inappropriately in low-prevalence settings, leading to misinterpretations. In low-prevalence settings (e.g., 1% disease prevalence), a positive antigen test with 99% specificity and 64% sensitivity could have a high false-positive rate, but media and some clinicians often reported positives as conclusive without contextualizing prevalence. Conversely, negative antigen tests were sometimes taken as proof of non-infectivity, despite high false-negative rates in early infection.

False negatives in PCR tests were a significant issue, particularly when testing was done too early or late in the infection cycle. A 2020 study in Annals of Internal Medicine found that the false-negative rate of PCR tests varied by time since exposure, peaking at 20–67% depending on the day of testing. Clinicians who relied solely on a negative PCR result without considering symptoms or exposure history often reassured patients they were not infected, potentially allowing transmission.

In low-prevalence settings, even highly specific tests like PCR (specificity ~99%) could produce false positives, especially with high cycle threshold (Ct) values indicating low viral loads. A 2020 study in Clinical Infectious Diseases found that only 15.6% of positive PCR results in low pre-test probability groups (e.g., asymptomatic screening) were confirmed by an alternate assay, suggesting a high false-positive rate. Media amplification of positive cases without context fueled public alarm, particularly during mass testing campaigns.

Antigen tests, while rapid, had lower sensitivity and were prone to false positives in low-prevalence settings. An oddly credible 2021 Guardian article noted that at a prevalence of 0.3% (1 in 340), a lateral flow test with 99.9% specificity could still yield a 5% false-positive rate among positives, causing unnecessary isolation or panic. In early 2020, widespread testing of asymptomatic individuals in low-prevalence areas led to false positives being reported as “new cases,” inflating perceived risk.

Many Covid professionals mitigated errors with Bayesian reasoning, using pre-test probability, test sensitivity, and specificity to calculate the post-test probability of disease. Experts who applied this approach were better equipped to interpret COVID-19 test results accurately, avoiding over-reliance on binary positive/negative outcomes.

Robert Wachter, MD, in a 2020 Medium article, explained Bayesian reasoning for COVID-19 testing, stressing that test results must be interpreted with pre-test probability. For example, a negative PCR in a patient with a 30% pre-test probability (based on symptoms and prevalence) still carried a significant risk of infection, guiding better clinical decisions. In Germany, mathematical models incorporating pre-test probability optimized PCR allocation, ensuring testing was targeted to high-risk groups.

Cases vs. Deaths (5)

One of the most persistent statistical missteps during the pandemic was the policy focus on case counts, devoid of context. Case numbers ballooned or dipped not only due to viral spread but due to shifts in testing volume, availability, and policies. Covid deaths per capita rather than case count would have served as a more stable measure of public health impact. Infection fatality rates would have been better still.

There was a persistent policy emphasis on cases alone. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, public health policies, such as lockdowns, mask mandates, and school closures, were often justified by rising case counts reported by agencies like the CDC, WHO, and national health departments. For example, in March 2020, the WHO’s situation reports emphasized confirmed cases as a primary metric, influencing global policy responses. In the U.S., states like California and New York tied reopening plans to case thresholds (e.g., California’s Blueprint for a Safer Economy, August 2020), prioritizing case numbers over other metrics. Over-reliance on case-based metrics was documented by Trisha Greenhalgh in Lancet (Ten scientific reasons in support of airborne transmission…).

Case counts, without context, were frequently reported without contextualizing factors like testing rates or demographics, leading to misinterpretations. A 2021 BMJ article criticized the overreliance on case counts, noting they were used to “justify public health measures” despite their variability, supporting the claim of a statistical misstep. Media headlines, such as “U.S. Surpasses 100,000 Daily Cases” (CNN, November 4, 2020), amplified case counts, often without clarifying testing changes, fostering fear-driven policy decisions.

Case counts were directly tied to testing volume, which varied widely. In the U.S., testing increased from ~100,000 daily tests in April 2020 to over 2 million by November 2020 (CDC data). Surges in cases often coincided with testing ramps, e.g., the U.S. case peak in July 2020 followed expanded testing in Florida and Texas. Testing access was biased (in the statistical sense). Widespread testing including asymptomatic screening inflated counts. Policies like mandatory testing for hospital admissions or travel (e.g., New York’s travel testing mandate, November 2020) further skewed numbers. 2020 Nature study highlighted that case counts were “heavily influenced by testing capacity,” with countries like South Korea detecting more cases due to aggressive testing, not necessarily higher spread. This supports the claim that testing volume drove case fluctuations beyond viral spread (J Peto, Nature – 2020).

Early in the pandemic, testing was limited due to supply chain issues and regulatory delays. For example, in March 2020, the U.S. conducted fewer than 10,000 tests daily due to shortages of reagents and swabs, underreporting cases (Johns Hopkins data). This artificially suppressed case counts. A 2021 Lancet article (R Horton) noted that “changes in testing availability distorted case trends,” with low availability early on masking true spread and later increases detecting more asymptomatic cases, aligning with the claim.

Testing policies, such as screening asymptomatic populations or requiring tests for specific activities, directly impacted case counts. For example, in China, mass testing of entire cities like Wuhan in May 2020 identified thousands of cases, many asymptomatic, inflating counts. In contrast, restrictive policies early on (e.g., U.S. CDC’s initial criteria limiting tests to symptomatic travelers, February 2020) suppressed case detection.

In the U.S., college campuses implementing mandatory weekly testing in fall 2020 reported case spikes, often driven by asymptomatic positives (e.g., University of Wisconsin’s 3,000+ cases, September 2020). A 2020 Science study (Assessment of SARS-CoV-2 screening) emphasized that “testing policy changes, such as expanded screening, directly alter reported case numbers,” supporting the claim that policy shifts drove case variability.

Deaths per capita, calculated as total Covid-19 deaths divided by population, are less sensitive to testing variations than case counts. For example, Sweden’s deaths per capita (1,437 per million by December 2020, Our World in Data) provided a clearer picture of impact than its case counts, which fluctuated with testing policies. Belgium and the U.K. used deaths per capita to compare regional impacts, guiding resource allocation. A 2021 JAMA study argued deaths per capita were a “more reliable indicator” of pandemic severity, as they reflected severe outcomes less influenced by testing artifacts. Death reporting had gross inconsistencies (e.g., defining “Covid-19 death”), but it was more standardized than case detection.

Infection Fatality Rates (IFR) reports the proportion of infections resulting in death, making it less prone to testing biases. A 2020 Bulletin of the WHO meta-analysis estimated a global IFR of ~0.6% (range 0.3-1.0%), varying by age and region. IFR gave a truer measure of lethality. Seroprevalence studies in New York City (April 2020) estimated an IFR of ~0.7%, offering insight into true mortality risk compared to case fatality rates (CFR), which were inflated by low testing (e.g., CFR ~6% in the U.S., March 2020).

Shifting Guidelines and Aerosol Transmission (6)

The “6-foot rule” was based on outdated models of droplet transmission. When evidence of aerosol spread emerged, guidance failed to adapt. Critics pointed out the statistical conservatism in risk modeling, its impact on mental health and the economy. Institutional inertia and politics prevented vital course corrections.

The 6-foot (or 2-meter) social distancing guideline, widely adopted by the CDC and WHO in early 2020, stemmed from historical models of respiratory disease transmission, particularly the 1930s work of William F. Wells on tuberculosis. Wells’ droplet model posited that large respiratory droplets fall within 1–2 meters, implying that maintaining this distance reduces transmission risk. The CDC’s March 2020 guidance explicitly recommended “at least 6 feet” based on this model, assuming most SARS-CoV-2 transmission occurred via droplets.

The droplet model was developed before modern understanding of aerosol dynamics. It assumed that only large droplets (>100 μm) were significant, ignoring smaller aerosols (<5–10 μm) that can travel farther and remain airborne longer. A 2020 Nature article noted that the 6-foot rule was rooted in “decades-old assumptions” about droplet size, which did not account for SARS-CoV-2’s aerosol properties, such as its ability to spread in poorly ventilated spaces beyond 6 feet.

Studies, like a 2020 Lancet article by Morawska and Milton, argued that the 6-foot rule was inadequate for aerosolized viruses, as aerosols could travel tens of meters in certain conditions (e.g., indoor settings with low air exchange). Real-world examples, such as choir outbreaks (e.g., Skagit Valley, March 2020, where 53 of 61 singers were infected despite spacing), highlighted transmission beyond 6 feet, undermining the droplet-only model.

The WHO initially downplayed aerosol transmission, stating in March 2020 that COVID-19 was “not airborne” except in specific medical procedures (e.g., intubation). After the July 2020 letter, the WHO updated its guidance on July 9, 2020, to acknowledge “emerging evidence” of airborne spread but maintained droplet-focused measures (e.g., 1-meter distancing) without emphasizing ventilation or masks for aerosols. A 2021 BMJ article criticized the WHO for “slow and risk-averse” updates, noting that full acknowledgment of aerosol spread was delayed until May 2021.

The CDC also failed to update its guidance. In May 2020, it emphasized droplet transmission and 6-foot distancing. A brief September 2020 update mentioning “small particles” was retracted days later, reportedly due to internal disagreement. The CDC fully updated its guidance to include aerosol transmission in May 2021, recommending improved ventilation, but retained the 6-foot rule in many contexts (e.g., schools) until 2022. Despite aerosol evidence, the 6-foot rule remained a cornerstone of policies. For example, U.S. schools enforced 6-foot desk spacing in 2020–2021, delaying reopenings despite studies (e.g., a 2021 Clinical Infectious Diseases study).

Early CDC and WHO models overestimated droplet transmission risks while underestimating aerosol spread, leading to rigid distancing rules. A 2021 PNAS article by Prather et al. criticized these models as “overly conservative,” noting they ignored aerosol physics and real-world data showing low outdoor transmission risks. Risk models overemphasized close-contact droplet spread, neglecting long-range aerosol risks in indoor settings. John Ioannidis, in a 2020 European Journal of Clinical Investigation commentary, criticized the “precautionary principle” in modeling, which prioritized avoiding any risk over data-driven adjustments, leading to policies like prolonged school closures based on conservative assumptions about transmission.

Risk models rarely incorporated Bayesian updates with new data, specifically low transmission in well-ventilated spaces. A 2020 Nature commentary by Tang et al. noted that models failed to adjust for aerosol decay rates or ventilation, overestimating risks in outdoor settings while underestimating them indoors.

Researchers and public figures criticized prolonged social distancing and lockdowns, driven by conservative risk models, for exacerbating mental health issues. A 2021 The Lancet Psychiatry study reported a 25% global increase in anxiety and depression in 2020, attributing it to isolation from distancing measures. Jay Bhattacharya, co-author of the Great Barrington Declaration, argued in 2020 that rigid distancing rules, like the 6-foot mandate, contributed to social isolation without proportional benefits.

Tragically, A 2021 JAMA Pediatrics study concluded that Covid school closures increased adolescent suicide ideation by 12–15%. Economists and policy analysts, such as those at the American Institute for Economic Research (AIER), criticized the economic fallout of distancing policies. The 6-foot rule led to capacity restrictions in businesses (e.g., restaurants, retail), contributing to economic losses. A 2020 Nature Human Behaviour study estimated a 13% global GDP decline in Q2 2020 due to lockdowns and distancing measures.

Institutional inertia and political agendas prevented course corrections, such as prioritizing ventilation over rigid distancing. The WHO’s delay in acknowledging aerosols was attributed to political sensitivities. A 2020 Nature article (Lewis) reported that WHO advisors faced pressure to align with member states’ policies, slowing updates.

Next post, I’ll offer commentary on Covid policy from the perspective of a historian of science.

Statistical Reasoning in Healthcare: Lessons from Covid-19

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science, Philosophy of Science, Probability and Risk on May 6, 2025

For centuries, medicine has navigated the tension between science and uncertainty. The Covid pandemic exposed this dynamic vividly, revealing both the limits and possibilities of statistical reasoning. From diagnostic errors to vaccine communication, the crisis showed that statistics is not just a technical skill but a philosophical challenge, shaping what counts as knowledge, how certainty is conveyed, and who society trusts.

Historical Blind Spot

Medicine’s struggle with uncertainty has deep roots. In antiquity, Galen’s reliance on reasoning over empirical testing set a precedent for overconfidence insulated by circular logic. If his treatments failed, it was because the patient was incurable. Enlightenment physicians, like those who bled George Washington to death, perpetuated this resistance to scrutiny. Voltaire wrote, “The art of medicine consists in amusing the patient while nature cures the disease.” The scientific revolution and the Enlightenment inverted Galen’s hierarchy, yet the importance of that reversal is often neglected, even by practitioners. Even in the 20th century, pioneers like Ernest Codman faced ostracism for advocating outcome tracking, highlighting a medical culture that prized prestige over evidence. While evidence-based practice has since gained traction, a statistical blind spot persists, rooted in training and tradition.

The Statistical Challenge

Physicians often struggle with probabilistic reasoning, as shown in a 1978 Harvard study where only 18% correctly applied Bayes’ Theorem to a diagnostic test scenario (a disease with 1/1,000 prevalence and a 5% false positive rate yields a ~2% chance of disease given a positive test). A 2013 follow-up showed marginal improvement (23% correct). Medical education, which prioritizes biochemistry over probability, is partly to blame. Abusive lawsuits, cultural pressures for decisiveness, and patient demands for certainty further discourage embracing doubt, as Daniel Kahneman’s work on overconfidence suggests.

Neil Ferguson and the Authority of Statistical Models

Epidemiologist Neil Ferguson and his team at Imperial College London produced a model in March 2020 predicting up to 500,000 UK deaths without intervention. The US figure could top 2 million. These weren’t forecasts in the strict sense but scenario models, conditional on various assumptions about disease spread and response.

Ferguson’s model was extraordinarily influential, shifting the UK and US from containment to lockdown strategies. It also drew criticism for opaque code, unverified assumptions, and the sheer weight of its political influence. His eventual resignation from the UK’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) over a personal lockdown violation further politicized the science.

From the perspective of history of science, Ferguson’s case raises critical questions: When is a model scientific enough to guide policy? How do we weigh expert uncertainty under crisis? Ferguson’s case shows that modeling straddles a line between science and advocacy. It is, in Kuhnian terms, value-laden theory.

The Pandemic as a Pedagogical Mirror

The pandemic was a crucible for statistical reasoning. Successes included the clear communication of mRNA vaccine efficacy (95% relative risk reduction) and data-driven ICU triage using the SOFA score, though both had limitations. Failures were stark: clinicians misread PCR test results by ignoring pre-test probability, echoing the Harvard study’s findings, while policymakers fixated on case counts over deaths per capita. The “6-foot rule,” based on outdated droplet models, persisted despite disconfirming evidence, reflecting resistance to updating models, inability to apply statistical insights, and institutional inertia. Specifics of these issues are revealing.

Mostly Positive Examples:

- Risk Communication in Vaccine Trials (1)

The early mRNA vaccine announcements in 2020 offered clear statistical framing by emphasizing a 95% relative risk reduction in symptomatic COVID-19 for vaccinated individuals compared to placebo, sidelining raw case counts for a punchy headline. While clearer than many public health campaigns, this focus omitted absolute risk reduction and uncertainties about asymptomatic spread, falling short of the full precision needed to avoid misinterpretation. - Clinical Triage via Quantitative Models (2)

During peak ICU shortages, hospitals adopted the SOFA score, originally a tool for assessing organ dysfunction, to guide resource allocation with a semi-objective, data-driven approach. While an improvement over ad hoc clinical judgment, SOFA faced challenges like inconsistent application and biases that disadvantaged older or chronically ill patients, limiting its ability to achieve fully equitable triage. - Wastewater Epidemiology (3)

Public health researchers used viral RNA in wastewater to monitor community spread, reducing the sampling biases of clinical testing. This statistical surveillance, conducted outside clinics, offered high public health relevance but faced biases and interpretive challenges that tempered its precision.

Mostly Negative Examples:

- Misinterpretation of Test Results (4)

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, many clinicians and media figures misunderstood diagnostic test accuracy, misreading PCR and antigen test results by overlooking pre-test probability. This caused false reassurance or unwarranted alarm, though some experts mitigated errors with Bayesian reasoning. This was precisely the type of mistake highlighted in the Harvard study decades earlier. - Cases vs. Deaths (5)

One of the most persistent statistical missteps during the pandemic was the policy focus on case counts, devoid of context. Case numbers ballooned or dipped not only due to viral spread but due to shifts in testing volume, availability, and policies. COVID deaths per capita rather than case count would have served as a more stable measure of public health impact. Infection fatality rates would have been better still. - Shifting Guidelines and Aerosol Transmission (6)

The “6-foot rule” was based on outdated models of droplet transmission. When evidence of aerosol spread emerged, guidance failed to adapt. Critics pointed out the statistical conservatism in risk modeling, its impact on mental health and the economy. Institutional inertia and politics prevented vital course corrections.

(I’ll defend these six examples in another post.)

A Philosophical Reckoning

Statistical reasoning is not just a mathematical tool – it’s a window into how science progresses, how it builds trust, and its special epistemic status. In Kuhnian terms, the pandemic exposed the fragility of our current normal science. We should expect methodological chaos and pluralism within medical knowledge-making. Science during COVID-19 was messy, iterative, and often uncertain – and that’s in some ways just how science works.

This doesn’t excuse failures in statistical reasoning. It suggests that training in medicine should not only include formal biostatistics, but also an eye toward history of science – so future clinicians understand the ways that doubt, revision, and context are intrinsic to knowledge.

A Path Forward

Medical education must evolve. First, integrate Bayesian philosophy into clinical training, using relatable case studies to teach probabilistic thinking. Second, foster epistemic humility, framing uncertainty as a strength rather than a flaw. Third, incorporate the history of science – figures like Codman and Cochrane – to contextualize medicine’s empirical evolution. These steps can equip physicians to navigate uncertainty and communicate it effectively.

Conclusion

Covid was a lesson in the fragility and potential of statistical reasoning. It revealed medicine’s statistical struggles while highlighting its capacity for progress. By training physicians to think probabilistically, embrace doubt, and learn from history, medicine can better manage uncertainty – not as a liability, but as a cornerstone of responsible science. As John Heilbron might say, medicine’s future depends not only on better data – but on better historical memory, and the nerve to rethink what counts as knowledge.

______

All who drink of this treatment recover in a short time, except those whom it does not help, all of whom die. It is obvious, therefore, that it fails only in incurable cases. – Galen

Extraordinary Popular Miscarriages of Science, Part 6 – String Theory

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science, Philosophy of Science on May 3, 2025

Introduction: A Historical Lens on String Theory

In 2006, I met John Heilbron, widely credited with turning the history of science from an emerging idea into a professional academic discipline. While James Conant and Thomas Kuhn laid the intellectual groundwork, it was Heilbron who helped build the institutions and frameworks that gave the field its shape. Through John I came to see that the history of science is not about names and dates – it’s about how scientific ideas develop, and why. It explores how science is both shaped by and shapes its cultural, social, and philosophical contexts. Science progresses not in isolation but as part of a larger human story.

The “discovery” of oxygen illustrates this beautifully. In the 18th century, Joseph Priestley, working within the phlogiston theory, isolated a gas he called “dephlogisticated air.” Antoine Lavoisier, using a different conceptual lens, reinterpreted it as a new element – oxygen – ushering in modern chemistry. This was not just a change in data, but in worldview.

When I met John, Lee Smolin’s The Trouble with Physics had just been published. Smolin, a physicist, critiques string theory not from outside science but from within its theoretical tensions. Smolin’s concerns echoed what I was learning from the history of science: that scientific revolutions often involve institutional inertia, conceptual blind spots, and sociopolitical entanglements.

My interest in string theory wasn’t about the physics. It became a test case for studying how scientific authority is built, challenged, and sustained. What follows is a distillation of 18 years of notes – string theory seen not from the lab bench, but from a historian’s desk.

A Brief History of String Theory

Despite its name, string theory is more accurately described as a theoretical framework – a collection of ideas that might one day lead to testable scientific theories. This alone is not a mark against it; many scientific developments begin as frameworks. Whether we call it a theory or a framework, it remains subject to a crucial question: does it offer useful models or testable predictions – or is it likely to in the foreseeable future?

String theory originated as an attempt to understand the strong nuclear force. In 1968, Gabriele Veneziano introduced a mathematical formula – the Veneziano amplitude – to describe the scattering of strongly interacting particles such as protons and neutrons. By 1970, Pierre Ramond incorporated supersymmetry into this approach, giving rise to superstrings that could account for both fermions and bosons. In 1974, Joël Scherk and John Schwarz discovered that the theory predicted a massless spin-2 particle with the properties of the hypothetical graviton. This led them to propose string theory not as a theory of the strong force, but as a potential theory of quantum gravity – a candidate “theory of everything.”

Around the same time, however, quantum chromodynamics (QCD) successfully explained the strong force via quarks and gluons, rendering the original goal of string theory obsolete. Interest in string theory waned, especially given its dependence on unobservable extra dimensions and lack of empirical confirmation.