Posts Tagged History of Science

Can Science Survive?

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science, Philosophy of Science on February 16, 2016

In my last post I ended with the question of whether science in the pure sense can withstand science in the corporate, institutional, and academic senses. Here’s a bit more on the matter.

Ronald Reagan, pandering to a church group in Dallas, famously said about evolution, “Well, it is a theory. It is a scientific theory only.” (George Bush, often “quoted” as saying this, did not.) Reagan was likely ignorant of the distinction between two uses of the word, theory. On the street, “theory” means an unsettled conjecture. In science a theory – gravitation for example – is a body of ideas that explains observations and makes predictions. Reagan’s statement fueled years of appeals to teach creationism in public schools, using titles like creation science and intelligent design. While the push for creation science is usually pinned on southern evangelicals, it was UC Berkeley law professor Phillip E Johnson who brought us intelligent design.

Arkansas was a forerunner in mandating equal time for creation science. But its Act 590 of 1981 (Balanced Treatment for Creation-Science and Evolution-Science Act) was shut down a year later by McLean v. Arkansas Board of Education. Judge William Overton made philosophy of science proud with his set of demarcation criteria. Science, said Overton:

- is guided by natural law

- is explanatory by reference to natural law

- is testable against the empirical world

- holds tentative conclusions

- is falsifiable

For earlier thoughts on each of Overton’s five points, see, respectively, Isaac Newton, Adelard of Bath, Francis Bacon, Thomas Huxley, and Karl Popper.

In the late 20th century, religious fundamentalists were just one facet of hostility toward science. Science was also under attack on the political and social fronts, as well an intellectual or epistemic front.

President Eisenhower, on leaving office in 1960, gave his famous “military industrial complex” speech warning of the “danger that public policy could itself become the captive of a scientific technological elite.” At about the same time the growing anti-establishment movements – perhaps centered around Vietnam war protests – vilified science for selling out to corrupt politicians, military leaders and corporations. The ethics of science and scientists were under attack.

Also at the same time, independently, an intellectual critique of science emerged claiming that scientific knowledge necessarily contained hidden values and judgments not based in either objective observation (see Francis Bacon) or logical deduction (See Rene Descartes). French philosophers and literary critics Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida argued – nontrivially in my view – that objectivity and value-neutrality simply cannot exist; all knowledge has embedded ideology and cultural bias. Sociologists of science ( the “strong program”) were quick to agree.

This intellectual opposition to the methodological validity of science, spurred by the political hostility to the content of science, ultimately erupted as the science wars of the 1990s. To many observers, two battles yielded a decisive victory for science against its critics. The first was publication of Higher Superstition by Gross and Levitt in 1994. The second was a hoax in which Alan Sokal submitted a paper claiming that quantum gravity was a social construct along with other postmodern nonsense to a journal of cultural studies. After it was accepted and published, Sokal revealed the hoax and wrote a book denouncing sociology of science and postmodernism.

Sadly, Sokal’s book, while full of entertaining examples of the worst of postmodern critique of science, really defeats only the most feeble of science’s enemies, revealing a poor grasp of some of the subtler and more valid criticism of science. For example, the postmodernists’ point that experimentation is not exactly the same thing as observation has real consequences, something that many earlier scientists themselves – like Robert Boyle and John Herschel – had wrestled with. Likewise, Higher Superstition, in my view, falls far below what we expect from Gross and Levitt. They deal Bruno Latour a well-deserved thrashing for claiming that science is a completely irrational process, and for the metaphysical conceit of holding that his own ideas on scientific behavior are fact while scientists’ claims about nature are not. But beyond that, Gross and Levitt reveal surprisingly poor knowledge of history and philosophy of science. They think Feyerabend is anti-science, they grossly misread Rorty, and waste time on a lot of strawmen.

Following closely on the postmodern critique of science were the sociologists pursuing the social science of science. Their findings: it is not objectivity or method that delivers the outcome of science. In fact it is the interests of all scientists except social scientists that govern the output of scientific inquiry. This branch of Science and Technology Studies (STS), led by David Bloor at Edinburgh in the late 70s, overplayed both the underdetermination of theory by evidence and the concept of value-laden theories. These scientists also failed to see the irony of claiming a privileged position on the untenability of privileged positions in science. I.e., it is an absolute truth that there are no absolute truths.

While postmodern critique of science and facile politics in STC studies seem to be having a minor revival, the threats to real science from sociology, literary criticism and anthropology (I don’t mean that all sociology and anthropology are non-scientific) are small. But more subtle and possibly more ruinous threats to science may exist; and they come partly from within.

Modern threats to science seem more related to Eisenhower’s concerns than to the postmodernists. While Ike worried about the influence the US military had over corporations and universities (see the highly nuanced history of James Conant, Harvard President and chair of the National Defense Research Committee), Eisenhower’s concern dealt not with the validity of scientific knowledge but with the influence of values and biases on both the subjects of research and on the conclusions reached therein. Science, when biased enough, becomes bad science, even when scientists don’t fudge the data.

Pharmaceutical research is the present poster child of biased science. Accusations take the form of claims that GlaxoSmithKline knew that Helicobacter pylori caused ulcers – not stress and spicy food – but concealed that knowledge to preserve sales of the blockbuster drugs, Zantac and Tagamet. Analysis of those claims over the past twenty years shows them to be largely unsupported. But it seems naïve to deny that years of pharmaceutical companies’ mailings may have contributed to the premature dismissal by MDs and researchers of the possibility that bacteria could in fact thrive in the stomach’s acid environment. But while Big Pharma may have some tidying up to do, its opponents need to learn what a virus is and how vaccines work.

Pharmaceutical firms generally admit that bias, unconscious and of the selection and confirmation sort – motivated reasoning – is a problem. Amgen scientists recently tried to reproduce results considered landmarks in basic cancer research to study why clinical trials in oncology have such high failure rate. They reported in Nature that they were able to reproduce the original results in only six of 53 studies. A similar team at Bayer reported that only about 25% of published preclinical studies could be reproduced. That the big players publish analyses of bias in their own field suggests that the concept of self-correction in science is at least somewhat valid, even in cut-throat corporate science.

Some see another source of bad pharmaceutical science as the almost religious adherence to the 5% (+- 1.96 sigma) definition of statistical significance, probably traceable to RA Fisher’s 1926 The Arrangement of Field Experiments. The 5% false-positive probability criterion is arbitrary, but is institutionalized. It can be seen as a classic case of subjectivity being perceived as objectivity because of arbitrary precision. Repeat any experiment long enough and you’ll get statistically significant results within that experiment. Pharma firms now aim to prevent such bias by participating in a registration process that requires researchers to publish findings, good, bad or inconclusive.

Academic research should take note. As is often reported, the dependence of publishing on tenure and academic prestige has taken a toll (“publish or perish”). Publishers like dramatic and conclusive findings, so there’s a strong incentive to publish impressive results – too strong. Competitive pressure on 2nd tier publishers leads to their publishing poor or even fraudulent study results. Those publishers select lax reviewers, incapable of or unwilling to dispute authors. Karl Popper’s falsification model of scientific behavior, in this scenario, is a poor match for actual behavior in science. The situation has led to hoaxes like Sokal’s, but within – rather than across – disciplines. Publication of the nonsensical “Fuzzy”, Homogeneous Configurations by Marge Simpson and Edna Krabappel (cartoon character names) by the Journal of Computational Intelligence and Electronic Systems in 2014 is a popular example. Following Alan Sokal’s line of argument, should we declare the discipline of computational intelligence to be pseudoscience on this evidence?

Note that here we’re really using Bruno Latour’s definition of science – what scientists and related parties do with a body of knowledge in a network, rather than simply the body of knowledge. Should scientists be held responsible for what corporations and politicians do with their knowledge? It’s complicated. When does flawed science become bad science. It’s hard to draw the line; but does that mean no line needs to be drawn?

Environmental science, I would argue, is some of the worst science passing for genuine these days. Most of it exists to fill political and ideological roles. The Bush administration pressured scientists to suppress communications on climate change and to remove the terms “global warming” and “climate change” from publications. In 2005 Rick Piltz resigned from the U.S. Climate Change Science Program claiming that Bush appointee Philip Cooney had personally altered US climate change documents to lessen the strength of their conclusions. In a later congressional hearing, Cooney confirmed having done this. Was this bad science, or just bad politics? Was it bad science for those whose conclusions had been altered not to blow the whistle?

The science of climate advocacy looks equally bad. Lack of scientific rigor in the IPCC is appalling – for reasons far deeper than the hockey stick debate. Given that the IPCC started with the assertion that climate change is anthropogenic and then sought confirming evidence, it is not surprising that the evidence it has accumulated supports the assertion. Compelling climate models, like that of Rick Muller at UC Berkeley, have since given strong support for anthropogenic warming. That gives great support for the anthropogenic warming hypothesis; but gives no support for the IPCC’s scientific practices. Unjustified belief, true or false, is not science.

Climate change advocates, many of whom are credentialed scientists, are particularly prone to a mixing bad science with bad philosophy, as when evidence for anthropogenic warming is presented as confirming the hypothesis that wind and solar power will reverse global warming. Stanford’s Mark Jacobson, a pernicious proponent of such activism, does immeasurable damage to his own stated cause with his descent into the renewables fantasy.

Finally, both major climate factions stoop to tying their entire positions to the proposition that climate change has been measured (or not). That is, both sides are in implicit agreement that if no climate change has occurred, then the whole matter of anthropogenic climate-change risk can be put to bed. As a risk man observing the risk vector’s probability/severity axes – and as someone who buys fire insurance though he has a brick house – I think our science dollars might be better spent on mitigation efforts that stand a chance of being effective rather than on 1) winning a debate about temperature change in recent years, or 2) appeasing romantic ideologues with “alternative” energy schemes.

Science survived Abe Lincoln (rain follows the plow), Ronald Reagan (evolution just a theory) and George Bush (coercion of scientists). It will survive Barack Obama (persecution of deniers) and Jerry Brown and Al Gore (science vs. pronouncements). It will survive big pharma, cold fusion, superluminal neutrinos, Mark Jacobson, Brian Greene, and the Stanford propaganda machine. Science will survive bad science because bad science is part of science, and always has been. As Paul Feyerabend noted, Galileo routinely used propaganda, unfair rhetoric, and arguments he knew were invalid to advance his worldview.

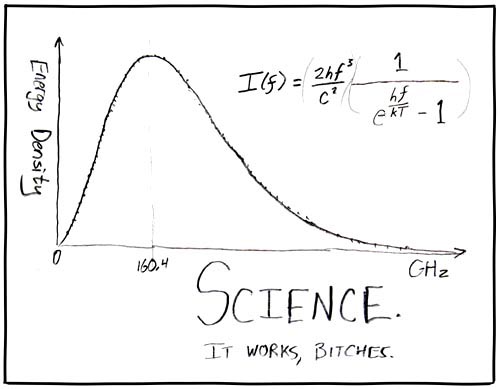

Theory on which no evidence can bear is religion. Theory that is indifferent to evidence is often politics. Granting Bloor, for sake of argument, that all theory is value-laden, and granting Kuhn, for sake of argument, that all observation is theory-laden, science still seems to have an uncanny knack for getting the world right. Planes fly, quantum tunneling makes DVD players work, and vaccines prevent polio. The self-corrective nature of science appears to withstand cranks, frauds, presidents, CEOs, generals and professors. As Carl Sagan Often said, science should withstand vigorous skepticism. Further, science requires skepticism and should welcome it, both from within and from irksome sociologists.

.

.

XKCD cartoon courtesy of xkcd.com

Science, God, and the White House

Posted by Bill Storage in Philosophy of Science on January 9, 2016

Back in the 80s I stumbled upon the book, Scientific Proof of the Existence of God Will Soon Be Announced by the White House!, by Franklin Jones, aka Frederick Jenkins, later Da Free John, later Adi Da Samraj. I bought it on the spot. Likely a typical 70s mystic charlatan, Jones nonetheless saw clearly our poor grasp of tools for seeking truth and saw how deep and misguided is our deference to authority. At least that’s how I took it.

Who’d expect a hippie mystic to be a keen philosopher of science. The book’s title, connecting science, church and state, shrewdly wraps four challenging ideas:

- That there can be such a thing as scientific proof of anything

- That there could be new findings about the existence of God

- That evidence for God could be in the realm of science

- That government should or could accredit a scientific theory

On the first point, few but the uneducated, TIME magazine, and the FDA think that proof is in the domain of science. Proof is deductive. It belongs to math, logic and analytic philosophy. Science uses evidence and induction to make inferences to the best explanation.

Accepting that strong evidence would suffice as proof, point number 2 is a bit trickier. Evidence of God’s existence can’t be ruled out a priori. God could be observable or detectable; we might see him or his consequences. An almighty god could easily have chosen to regularly show himself or to present unambiguous evidence. But Yahweh, at least in modern times, doesn’t play like that (A wicked and adulterous generation demands a sign but none will be given – Matthew 16:4). While believers often say no evidence would satisfy the atheist, I think a focused team could come up with rules for a demonstration that at least some nonbelievers would accept as sufficient evidence.

Barring any new observations that would constitute evidence, point number 3 is tough to tackle without wading deep into philosophy of science. To see why, consider the theory that God exists. Is it even a candidate for a scientific theory, as one WSJ writer thinks (Science Increasingly Makes the Case for God)? I.e., is it the content of a theory or the way it is handled by its advocates that makes the theory scientific? If the latter, it can be surprisingly hard to draw the line between scientific investigations and philosophical ones. Few scientists admit this line is so blurred, but how do string theorists, who make no confirmable or falsifiable predictions, defend that they are scientists? Their fondness for non-empirical theory confirmation puts them squarely in the ranks of the enlightenment empiricist, Bishop Berkeley of Cloyne (namesake of our fair university) who maintained that matter does not exist. Further, do social scientists make falsifiable predictions, or do they just continually adjust their theory to accommodate disconfirming evidence?

That aside, those who work in the God-theory space somehow just don’t seem to qualify as scientific – even the young-earth creationists trained in biology and geology. Their primary theory doesn’t seem to generate research and secondary theories to confirm or falsify. Their papers are aimed at the public, not peers – and mainly aim at disproving evolution. Can a scientific theory be primarily negative? Could plate-tectonics-is-wrong count as a proper scientific endeavor?

Gould held that God was simply outside the realm of science. But if we accept that the existence of God could be a valid topic of science, is it a good theory? Following Karl Popper, a scientific theory can withstand only a few false predictions. On that view the repeated failures of end-of-days predictions by Harold Camping and Herbert Armstrong might be sufficient to kill the theory of God’s existence. Or does their predictive failures simply exclude them from the community of competent practitioners?

Would NASA engineer, Edgar Whisenant be more credible at making predictions based on the theory of God’s existence? All his predictions of rapture also failed. He was accepted by the relevant community (“…in paradigm choice there is no standard higher than the assent of the relevant community” – Thomas Kuhn) since the Trinity Broadcast Network interrupted its normal programming to help watchers prepare. If a NASA engineer has insufficient scientific clout, how about our first scientist? Isaac Newton predicted, in Observations upon the Prophecies of Daniel and the Apocalypse of St. John, that the end would come in 2000 CE. Maybe Newton’s calculator had the millennium bug.

If we can’t reject the theory for any number of wrong predictions, might there be another basis for rejecting it? Some say absence of a clear mechanism is a good reason to reject theories. In the God theory, no one seems to have proposed a mechanism by which such a God could have arisen. Aquinas’s tortured teleology and Anselm’s ontological arguments still fail on this count. But it seems unfair to dismiss the theory of God’s existence on grounds of no clear mechanism, because we have long tolerated other theories deemed scientific with the same weakness. Gravity, for example.

Does assent of the relevant community grant scientific status to a theory, as Kuhn would have it? If so, who decides which community is the right one? Theologians spend far more time on Armageddon than do biologists and astrophysicists – and theologians are credentialed by their institutions. So why should Hawking and Dawkins get much air time on the matter? Once we’ve identified a relevant community, who gets to participate in its consensus?

This draws in point number 4, above. Should government or the White House have any more claim to a scientific pronouncement than the Council of Bishops? If not, what are we to think of the pronouncements by Al Gore and Jerry Brown that the science of climate is settled? Should they have more clout on the matter than Pope Francis (who, interestingly, has now made similar pronouncements)?

If God is outside the realm of science, should science be outside the jurisdiction of government? What do we make of President Obama’s endorsement of “calling out climate change deniers, one by one”? You don’t have to be Franklin Jones or Da Free John to see signs here of government using the tools of religion (persecution, systematic effort to censure and alienate dissenters) in the name of science. Is it a stretch to see a connection to Jean Bodin, late 16th century French jurist, who argued that only witches deny the existence of witches?

Can you make a meaningful distinction between our government’s pronouncements on the truth or settledness of the climate theory (as opposed to government’s role in addressing it) and the Kremlin’s 1948 pronouncement that only Lamarckian inheritance would be taught, and their call for all geneticists to denounce Mendelian inheritance? Is it scientific behavior for a majority in a relevant community to coerce dissenters?

In trying to draw a distinction between UN and US coercion on climate science and Lysenkoism, some might offer that we (we moderns or we Americans) are somehow different – that only under regimes like Lenin’s and Hitler’s does science get so distorted. In thinking this, it’s probably good to remember that Hitler’s eugenics was born right here, and flourished in the 20th century. It had nearly full academic support in America, including Stanford and Harvard. That is, to use Al Gore’s words, the science was settled. California, always a trendsetter, by the early 1920s, claimed 80% of America’s forced sterilizations. Charles Goethe, founder of Sacramento State University, after visiting Hitler’s Germany in 1934 bragged to a fellow California eugenicist about their program’s influence on Hitler.

If the era of eugenics seems too distant to be relevant to the issue of climate science/politics, consider that living Stanford scientist, Paul Ehrlich, who endorsed compulsory abortion in the 70s, has had a foot in both camps.

As crackpots go, Da Free John was rather harmless.

________

“Indeed, it has been concluded that compulsory population-control laws, even including laws requiring compulsory abortion, could be sustained under the existing Constitution if the population crisis became sufficiently severe to endanger the society.” – Ehrlich, Holdren and Ehrlich, EcoScience, 3rd edn, 1977, p. 837

“You will be interested to know that your work has played a powerful part in shaping the opinions of the group of intellectuals who are behind Hitler in this epoch-making program.” – Charles Goethe, letter to Edwin Black, 1934

Marcus Vitruvius’s Science

Posted by Bill Storage in Engineering & Applied Physics, Philosophy of Science on June 26, 2015

Science, as an enterprise that acquires knowledge and justified beliefs in the form of testable predictions by systematic iterations of observation and math-based theory, started around the 17th century, somewhere between Copernicus and Newton. That, we learned in school, was the beginning of the scientific revolution. Historians of science tend to regard this great revolution as the one that never happened. That is, as Floris Cohen puts it, the scientific revolution, once an innovative and inspiring concept, has since turned into a straight-jacket. Picking this revolution’s starting point, identifying any cause for it, and deciding what concepts and technological innovations belong to it are problematic.

That said, several writers have made good cases for why the pace of evolution – if not revolution – of modern science accelerated dramatically in Europe, only when it did, why it has continuously gained steam rather than petering out, its primary driving force, and the associated transformations in our view of how nature works. Some thought the protestant ethic and capitalism set the stage for science. Others thought science couldn’t emerge until the alliance between Christianity and Aristotelianism was dissolved. Moveable type and mass production of books can certainly claim a role, but was it really a prerequisite? Some think a critical mass of ancient Greek writings had to have been transferred to western Europe by the Muslims. The humanist literary critics that enabled repair and reconstruction of ancient texts mangled in translation from Greek to Syriac to Persian to Latin and botched by illiterate medieval scribes certainly played a part. If this sounds like a stretch, note that those critics seem to mark the first occurrence of a collective effort by a group spread across a large geographic space using shared standards to reach a peer-reviewed consensus – a process sharing much with modern science.

But those reasons given for the scientific revolution all have the feel of post hoc theorizing. Might intellectuals of the day, observing these events, have concluded that a resultant scientific revolution was on the horizon? Francis Bacon comes closest to fitting this bill, but his predictions gave little sense that he was envisioning anything like what really happened.

I’ve wondered why the burst of progress in science – as differentiated from plain know-how, nature-knowledge, art, craft, technique, or engineering knowledge – didn’t happen earlier. Why not just after the period of innovation in from about 1100 to 1300 CE in Europe. In this period Jean Buridan invented calculators and almost got the concept of inertia right. Robert Grosseteste hinted at the experiment-theory model of science. Nicole Oresme debunked astrology and gave arguments for a moving earth. But he was the end of this line. After this brief awakening, which also included the invention of banking and the university, progress came to a screeching halt. Some blame the plague, but that can’t be the culprit. Literature of the time barley mentions the plague. Despite the death toll, politics and war went on as usual; but interest in resurrecting ancient Greek knowledge of all sorts tanked.

Why not in the Islamic world in the time of Ali al-Qushji and al-Birjandi? Certainly the mental capacity was there. A layman would have a hard time distinguishing al-Birjandi’s arguments and thought experiments for the earth’s rotation from those of Galileo. But Islamic civilization at the time had plenty of scholars but no institutions for making practical use of such knowledge and its society would not have tolerated displacement of received wisdom by man-made knowledge.

The most compelling case for civilization having been on the brink of science at an earlier time seems to be the late republic or early imperial Rome. This may seem a stretch, since Rome is much more known for brute force than for finesse, despite their flying buttresses, cranes, fire engines, central heating and indoor plumbing.

Consider the writings of one Vitruvius, likely Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, in the early reign of Augustus. Vitruvius wrote De Architectura, a ten volume guide to Roman engineering knowledge. Architecture, in Latin, translates accurately into what we call engineering. Rediscovered and widely published during the European renaissance as a standard text for engineers, Vitruvius’s work contains text that seems to contradict what we were all taught about the emergence of the – or a – scientific method.

Consider the writings of one Vitruvius, likely Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, in the early reign of Augustus. Vitruvius wrote De Architectura, a ten volume guide to Roman engineering knowledge. Architecture, in Latin, translates accurately into what we call engineering. Rediscovered and widely published during the European renaissance as a standard text for engineers, Vitruvius’s work contains text that seems to contradict what we were all taught about the emergence of the – or a – scientific method.

Vitruvius is full of surprises. He acknowledges that he is not a scientist (an anachronistic but fitting term) but a collator of Greek learning from several preceding centuries. He describes vanishing point perspective: “…the method of sketching a front with the sides withdrawing into the background, the lines all meeting in the center of a circle.” (See photo below of a fresco in the Oecus at Villa Poppea, Oplontis showing construction lines for vanishing point perspective.) He covers acoustic considerations for theater design, explains central heating technology, and the Archimedian water screw used to drain mines. He mentions a steam engine, likely that later described by Hero of Alexandria (aeolipile drawing at right), which turns heat into rotational energy. He describes a heliocentric model passed down from ancient Greeks. To be sure, there is also much that Vitruvius gets wrong about physics. But so does Galileo.

Most of De Architectura is not really science; it could more accurately be called know-how, technology, or engineering knowledge. Yet it’s close. Vitruvius explains the difference between mere machines, which let men do work, and engines, which derive from ingenuity and allow storing energy.

What convinces me most that Vitruvius – and he surely could not have been alone – truly had the concept of modern scientific method within his grasp is his understanding that a combination of mathematical proof (“demonstration” in his terms) plus theory, plus hands-on practice are needed for real engineering knowledge. Thus he says that what we call science – theory plus math (demonstration) plus observation (practice) – is essential to good engineering.

The engineer should be equipped with knowledge of many branches of study and varied kinds of learning, for it is by his judgement that all work done by the other arts is put to test. This knowledge is the child of practice and theory. Practice is the continuous and regular exercise of employment where manual work is done with any necessary material according to the design of a drawing. Theory, on the other hand, is the ability to demonstrate and explain the productions of dexterity on the principles of proportion.

It follows, therefore, that engineers who have aimed at acquiring manual skill without scholarship have never been able to reach a position of authority to correspond to their pains, while those who relied only upon theories and scholarship were obviously hunting the shadow, not the substance. But those who have a thorough knowledge of both, like men armed at all points, have the sooner attained their object and carried authority with them.

It appears, then, that one who professes himself an engineer should be well versed in both directions. He ought, therefore, to be both naturally gifted and amenable to instruction. Neither natural ability without instruction nor instruction without natural ability can make the perfect artist. Let him be educated, skillful with the pencil, instructed in geometry, know much history, have followed the philosophers with attention, understand music, have some knowledge of medicine, know the opinions of the jurists, and be acquainted with astronomy and the theory of the heavens. – Vitruvius – De Architectura, Book 1

Historians, please correct me if you know otherwise, but I don’t think there’s anything else remotely like this on record before Isaac Newton – anything in writing that comes this close to an understanding of modern scientific method.

So what went wrong in Rome? Many blame Christianity for the demise of knowledge in Rome, but that is not the case here. We can’t know for sure, but the later failure of science in the Islamic world seems to provide a clue. Society simply wasn’t ready. Vitruvius and his ilk may have been ready for science, but after nearly a century of civil war (starting with the Italian social wars), Augustus, the senate, and likely the plebes, had seen too much social innovation that all went bad. The vision of science, so evident during the European Enlightenment, as the primary driver of social change, may have been apparent to influential Romans as well, at a time when social change had lost its luster. As seen in writings of Cicero and the correspondence between Pliny and Trajan, Rome now regarded social innovation with suspicion if not contempt. Roman society, at least its government and aristocracy, simply couldn’t risk the main byproduct of science – progress.

———————————-

History is not merely what happened: it is what happened in the context of what might have happened. – Hugh Trevor-Roper – Oxford Valedictorian Address, 1998

The affairs of the Empire of letters are in a situation in which they never were and never will be again; we are passing now from an old world into the new world, and we are working seriously on the first foundation of the sciences. – Robert Desgabets, Oeuvres complètes de Malebranche, 1676

Newton interjected historical remarks which were neither accurate nor fair. These historical lapses are a reminder that history requires every bit as much attention to detail as does science – and the history of science perhaps twice as much. – Carl Benjamin Boyer, The Rainbow: From Myth to Mathematics, 1957

Text and photos © 2015 William Storage

Sun Follows the Solar Car

Posted by Bill Storage in Engineering & Applied Physics, Sustainable Energy on January 25, 2014

Bill Storage once got an A in high school Physics and suggests no further credentials are needed to evaluate the claims of most eco-fraud.

Once a great debate raged in America over the matter of whether man-mad climate change had occurred. Most Americans believed that it had. There were theories, models, government-sponsored studies, and various factions arguing with religious fervor. The time was 1880 and the subject was whether rain followed the plow – whether the westward expansion of American settlers beyond the 100th meridian had caused an increase in rain that would make agricultural life possible in the west. When the relentless droughts of the 1890s offered conflicting evidence, the belief died off, leavings its adherents embarrassed for having taken part in a mass delusion.

We now know the dramatic greening of the west from 1845 to 1880 was due to weather, not climate. It was not brought on by Mormon settlements, vigorous tilling, or the vast amounts of dynamite blown off to raise dust around which clouds could form. There was a shred of scientific basis for the belief; but the scale was way off.

We now know the dramatic greening of the west from 1845 to 1880 was due to weather, not climate. It was not brought on by Mormon settlements, vigorous tilling, or the vast amounts of dynamite blown off to raise dust around which clouds could form. There was a shred of scientific basis for the belief; but the scale was way off.

It seems that the shred of science was not really a key component of the widespread belief that rain would follow the plow. More important was human myth-making and the madness of crowds. People got swept up in it. As ancient Jewish and Roman writings show, public optimism and pessimism ebbs and flows across decades. People confuse the relationship between man and nature. They either take undue blame or undo credit for processes beyond their influence, or they assign their blunders to implacable cosmic forces. The period of the Western Movement was buoyant, across political views and religions. Some modern writers force-fit the widely held belief about rain following the plow in the 1870s into the doctrine of Manifest Destiny. These embarrassing beliefs were in harmony, but were not tied genetically. In other words, don’t blame the myth that rain followed the plow on the Christian right.

Looking back, one wonders how farmers, investors and politicians, possibly including Abraham Lincoln, could so deeply indulge in belief held on irrational grounds rather than evidence and science. Do modern humans do the same? I’ll vote yes.

Today’s anthropogenic climate theories have a great deal more scientific basis than those of the 1870s. But many of our efforts at climate cure do not. Blame shameless greed for some of the greenwashing; but corporations wouldn’t waste their time if consumers weren’t willing to waste their dollars and hopes.

Take Ford’s solar-powered hybrid car, about which a SmartPlanet writer recently said:

Imagine an electric car that can charge without being plugged into an outlet and without using electricity from dirty energy sources, like coal.

He goes on to report that Ford plans to experiment with such a solar-hybrid concept car having a 620-mile range. I suspect many readers will understand that experimentation to mean experimenting in the science sense rather than in the marketability sense. Likewise I’m guessing many readers will allow themselves to believe that such a car might derive a significant part of the energy used in a 620-mile run from solar cells.

We can be 100% sure that Ford is not now experimenting on – nor will ever experiment on – a solar-powered car that will get a significant portion of its energy from solar cells. It’s impossible now, and always will be. No technology breakthrough can alter the laws of nature. Only so much solar energy hits the top of a car. Even if you collected every photon of it, which is again impossible because of other laws of physics, you couldn’t drive a car very far on it.

Most people – I’d guess – learned as much in high school science. Those who didn’t might ask themselves, based on common sense and perhaps seeing the size of solar panels needed to power a telephone in the desert, if a solar car seems reasonable.

The EPA reports that all-electric cars like the Leaf and Tesla S get about 3 miles per kilowatt-hour of energy. The top of a car is about 25 square feet. At noon on June 21st in Phoenix, a hypothetically perfect, spotless car-top solar panel could in theory generate 30 watts per square foot. You could therefore power half of a standard 1500 watt toaster with that car-top solar panel. If you drove your car in the summer desert sun for 6 hours and the noon sun magically followed it into the shade and into your garage – like rain following the plow – you could accumulate 4500 watt-hours (4.5 kilowatt hours) of energy, on which you could drive 13.5 miles, using the EPA’s numbers. But experience shows that 30 watts per square foot is ridiculously optimistic. Germany’s famous solar parks, for example, average less than one watt per square foot; their output is a few percent of my perpetual-noon-Arizona example. Where you live, it probably doesn’t stay noon, and you’re likely somewhat north of Phoenix, where the sun is far closer to the horizon, and it’s not June 21st all year (hint: sine of 35 degrees times x, assuming it’s not dark). Oh, and then there’s clouds. If you live in Bavaria or Cleveland, or if your car roof’s dirty – well, your mileage may vary.

Recall that this rather dim picture cannot be made much brighter by technology. Physical limits restrict the size of the car-top solar panel, nature limits the amount of sun that hits it, and the Shockley–Queisser limit caps the conversion efficiency of solar cells.

Curbing CO2 emissions is not a lost cause. We can apply real engineering to the problem. Solar panels on cars isn’t real engineering; it’s pandering to public belief. What would Henry Ford think?

—————————-

.

Tom Hight is my name, an old bachelor I am,

You’ll find me out West in the country of fame,

You’ll find me out West on an elegant plain,

And starving to death on my government claim.

Hurrah for Greer County!

The land of the free,

The land of the bed-bug,

Grass-hopper and flea;

I’ll sing of its praises

And tell of its fame,

While starving to death

On my government claim.

Opening lyrics to a folk song by Daniel Kelley, late 1800s

Great Innovative Minds: A Discord on Method

Posted by Bill Storage in Innovation management, Multidisciplinarians on November 19, 2013

Great minds do not think alike. Cognitive diversity has served us well. That’s not news to those who study innovation; but I think you’ll find this to be a different take on the topic, one that gets at its roots.

The two main figures credited with setting the scientific revolution in motion did not agree at all on what the scientific method actually was. It’s not that they differed on the finer points; they disagreed on the most basic aspect of what it meant to do science – though they didn’t yet use that term. At the time of Francis Bacon and Rene Descartes, there were no scientists. There were natural philosophers. This distinction is important for showing just how radical and progressive Descartes and Bacon were.

In Discourse on Method, Descartes argued that philosophers, over thousands of years of study, had achieved absolutely nothing. They pursued knowledge, but they had searched in vain. Descartes shared some views with Aristotle, but denied Aristotelian natural philosophy, which had been woven into Christian beliefs about nature. For Aristotle, rocks fell to earth because the natural order is for rocks to be on the earth, not above it – the Christian version of which was that it was God’s plan. In medieval Europe truths about nature were revealed by divinity or authority, not discovered. Descartes and Bacon were both devout Christians, but believed that Aristotelian philosophy of nature had to go. Observing that there is no real body of knowledge that can be claimed by philosophy, Descartes chose to base his approach to the study of nature on mathematics and reason. A mere 400 years after Descartes, we have trouble grasping just how radical this notion was. Descartes believed that the use of reason could give us knowledge of nature, and thus give us control over nature. His approach was innovative, in the broad sense of that term, which I’ll discuss below. Observation and experience, however, in Descartes’ view, could be deceptive. They had to be subdued by pure reason. His approach can be called rationalism. He sensed that we could use rationalism to develop theories – predictive models – with immense power, which would liberate mankind. He was right.

In Discourse on Method, Descartes argued that philosophers, over thousands of years of study, had achieved absolutely nothing. They pursued knowledge, but they had searched in vain. Descartes shared some views with Aristotle, but denied Aristotelian natural philosophy, which had been woven into Christian beliefs about nature. For Aristotle, rocks fell to earth because the natural order is for rocks to be on the earth, not above it – the Christian version of which was that it was God’s plan. In medieval Europe truths about nature were revealed by divinity or authority, not discovered. Descartes and Bacon were both devout Christians, but believed that Aristotelian philosophy of nature had to go. Observing that there is no real body of knowledge that can be claimed by philosophy, Descartes chose to base his approach to the study of nature on mathematics and reason. A mere 400 years after Descartes, we have trouble grasping just how radical this notion was. Descartes believed that the use of reason could give us knowledge of nature, and thus give us control over nature. His approach was innovative, in the broad sense of that term, which I’ll discuss below. Observation and experience, however, in Descartes’ view, could be deceptive. They had to be subdued by pure reason. His approach can be called rationalism. He sensed that we could use rationalism to develop theories – predictive models – with immense power, which would liberate mankind. He was right.

Francis Bacon, Descartes slightly older counterpart in the scientific revolution, was a British philosopher and statesman who became attorney general in 1613 under James I. He is now credited with being the father of empiricism, the hands-on, experimental basis for modern science, engineering, and technology. Bacon believed that acquiring knowledge of nature had to be rooted in observation and sensory experience alone. Do experiments and then decide what it means. Infer conclusions from the facts. Bacon argued that we must quiet the mind and apply a humble, mechanistic approach to studying nature and developing theories. Reason biases observation, he said. In this sense, the theory-building models of Bacon and Descartes were almost completely opposite. I’ll return to Bacon after a clarification of terms needed to make a point about him.

Innovation has many meanings. Cicero said he regarded it with great suspicion. He saw innovation as the haphazard application of untested methods to important matters. For Cicero, innovators were prone to understating the risks and overstating the potential gains to the public, while the innovators themselves had a more favorable risk/reward quotient. If innovation meant dictatorship for life for Julius Caesar after 500 years of self-governance by the Roman people, Cicero’s position might be understandable.

Today, innovation usually applies specifically to big changes in commercial products and services, involving better consumer value, whether by new features, reduced prices, reduced operator skill level, or breaking into a new market. Peter Drucker, Clayton Christensen and the tech press use innovation in roughly this sense. It is closely tied to markets, and is differentiated from invention (which may not have market impact), improvement (may be merely marginal), and discovery.

That business-oriented definition of innovation is clear and useful, but it leaves me with no word for what earlier generations meant by innovation. In a broader sense, it seems fair that innovation also applies to what vanishing point perspective brought to art during the renaissance. John Locke, a follower of both Bacon and Descartes, and later Thomas Jefferson and crew, conceived of the radical idea that a nation could govern itself by the application of reason. Discovery, invention and improvement don’t seem to capture the work of Locke and Jefferson either. Innovation seems the best fit. So for discussion purposes, I’ll call this innovation in the broader sense as opposed to the narrower sense, where it’s tied directly to markets.

That business-oriented definition of innovation is clear and useful, but it leaves me with no word for what earlier generations meant by innovation. In a broader sense, it seems fair that innovation also applies to what vanishing point perspective brought to art during the renaissance. John Locke, a follower of both Bacon and Descartes, and later Thomas Jefferson and crew, conceived of the radical idea that a nation could govern itself by the application of reason. Discovery, invention and improvement don’t seem to capture the work of Locke and Jefferson either. Innovation seems the best fit. So for discussion purposes, I’ll call this innovation in the broader sense as opposed to the narrower sense, where it’s tied directly to markets.

In the broader sense, Descartes was the innovator of his century. But in the narrow sense (the business and markets sense), Francis Bacon can rightly be called the father of innovation – and it’s first vocal advocate. Bacon envisioned a future where natural philosophy (later called science) could fuel industry, prosperity and human progress. Again, it’s hard to grasp how radical this was; but in those days the dominant view was that mankind had reached its prime in ancient times, and was on a downhill trajectory. Bacon’s vision was a real departure from the reigning view that philosophy, including natural philosophy, was stuff of the mind and the library, not a call to action or a route to improving life. Historian William Hepworth Dixon wrote in 1862 that everyone who rides in a train, sends a telegram or undergoes a painless surgery owes something to Bacon. In 1620, Bacon made, in The Great Instauration, an unprecedented claim in the post-classical world:

“The explanation of which things, and of the true relation between the nature of things and the nature of the mind … may spring helps to man, and a line and race of inventions that may in some degree subdue and overcome the necessities and miseries of humanity.”

In Bacon’s view, such explanations would stem from a mechanistic approach to investigation; and it must steer clear of four dogmas, which he called idols. Idols of the tribe are the set of ambient cultural prejudices. He cites our tendency to respond more strongly to positive evidence than to negative evidence, even if they are equally present; we leap to conclusions. Idols of the cave are one’s individual preconceptions that must be overcome. Idols of the theater refer to dogmatic academic beliefs and outmoded philosophies; and idols of the marketplace are those prejudices stemming from social interactions, specifically semantic equivocation and terminological disputes.

Descartes realized that if you were to strictly follow Bacon’s method of fact collecting, you’d never get anything done. Without reasoning out some initial theoretical model, you could collect unrelated facts forever with little chance of developing a usable theory. Descartes also saw Bacon’s flaw in logic to be fatal. Bacon’s method (pure empiricism) commits the logical sin of affirming the consequent. That is, the hypothesis, if A then B, is not made true by any number of observations of B. This is because C, D or E (and infinitely more letters) might also cause B, in the absence of A. This logical fallacy had been well documented by the ancient Greeks, whom Bacon and Descartes had both studied. Descartes pressed on with rationalism, developing tools like analytic geometry and symbolic logic along the way.

Interestingly, both Bacon and Descartes were, from our perspective, rather miserable scientists. Bacon denied Copernicanism, refused to accept Kepler’s conclusion that planet orbits were elliptical, and argued against William Harvey’s conclusion that the heart pumped blood to the brain through a circulatory system. Likewise, by avoiding empiricism, Descartes reached some very wrong conclusions about space, matter, souls and biology, even arguing that non-human animals must be considered machines, not organisms. But their failings were all corrected by time and the approaches to investigation they inaugurated. The tension between their approaches didn’t go unnoticed by their successors. Isaac Newton took a lot from Bacon and a little from Descartes; his rival Gottfried Leibniz took a lot from Descartes and a little from Bacon. Both were wildly successful. Science made the best of it, striving for deductive logic where possible, but accepting the problems of Baconian empiricism. Despite reliance on affirming the consequent, inductive science seems to work rather well, especially if theories remain open to revision.

Bacon’s idols seem to be as relevant to the boardroom as they were to the court of James I. Seekers of innovation, whether in the classroom or in the enterprise, might do well to consider the approaches and virtues of Bacon and Descartes, of contrasting and fusing rationalism and observation. Bacon and Descartes envisioned a brighter future through creative problem-solving. They broke the bonds of dogma and showed that a new route forward was possible. Let’s keep moving, with a diversity of perspectives, interpretations, and predictive models.

Just a Moment, Galileo

Posted by Bill Storage in Engineering & Applied Physics, Innovation management on October 29, 2013

Bruce Vojak’s wonderful piece on innovation and the minds of Newton and Goethe got me thinking about another 17th century innovator. Like Newton, Galileo was a superstar in his day – a status he still holds. He was the consummate innovator and iconoclast. I want to take a quick look at two of Galileo’s errors, one technical and one ethical, not to try to knock the great man down a peg, but to see what lessons they can bring to the innovation, engineering and business of this era.

Less well known than his work with telescopes and astronomy was Galileo’s work in mechanics of solids. He seems to have been the first to explicitly identify that the tensile strength of a beam is proportional to its cross-sectional area, but his theory of bending stress was way off the mark. He applied similar logic to cantilever beam loading, getting very incorrect results. Galileo’s bending stress illustration is shown below (you can skip over the physics details, but they’re not all that heavy).

For bending, Galileo concluded that the whole cross section was subjected to tension at the time of failure. He judged that point B in the diagram at right served as a hinge point, and that everything above it along the line A-B was uniformly in horizontal tension. Thus he missed what would be elementary to any mechanical engineering sophomore; this view of the situation’s physics results in an unresolved moment (tendency to twist, in engineer-speak). Since the cantilever is at rest and not spinning, we know that this model of reality cannot be right. In Galileo’s defense, Newton’s 3rd law (equal and opposite reaction) had not yet been formulated; Newton was born a year after Galileo died. But Newton’s law was an assumption derived from common sense, not from testing.

It took more than a hundred years (see Bernoulli and Euler) to finally get the full model of beam bending right. But laboratory testing in Galileo’s day could have shown his theory of bending stress to make grossly conservative predictions. And long before Bernuolli and Euler, Edme Mariotte published an article in which he got the bending stress distribution mostly right, identifying that the neutral axis should be down the center of the beam, from top to bottom. A few decades later Antoine Parent polished up Mariotte’s work, arriving at a modern conception of bending stress.

But Mariotte and Parent weren’t superstars. Manuals of structural design continued to publish Galileo’s equation, and trusting builders continued to use them. Beams broke and people died. Deference to Galileo’s authority, universally across his domain of study, not only led to needless deaths but also to the endless but fruitless pursuit of other causes for reality’s disagreement with theory.

So the problem with Galileo’s error in beam bending was not so much the fact that he made this error, but the fact that for a century it was missed largely for social reasons. The second fault I find with Galileo’s method is intimately tied to his large ego, but that too has a social component. This fault is evident in Galileo’s writing of Dialogue on the Two Chief World Systems, the book that got him condemned for heresy.

Galileo did not invent the sun-centered model of our solar system; Copernicus did. Galileo pointed his telescope to the sky, discovered four moons of Jupiter, and named them after influential members of the Medici family, landing himself a job as the world’s highest paid scholar. No problem there; we all need to make a living. He then published Dialogue arguing for Copernican heliocentrism against the earth-centered Ptolemaic model favored by the church. That is, Galileo for the first time claimed that Copernicanism was not only an accurate predictive model, but was true. This was tough for 17th century Italians to swallow, not only their clergy.

For heliocentrism to be true, the earth would have to spin around at about 1000 miles per hour on its surface. Galileo had no good answer for why we don’t all fly off into space. He couldn’t explain why birds aren’t shredded by supersonic winds. He was at a loss to provide rationale for why balls dropped from towers appeared to fall vertically instead of at an angle, as would seem natural if the earth were spinning. And finally, if the earth is in a very different place in June than in December, why do the stars remain in the same pattern year round (why no parallax)? As UC Berkeley philosopher of science Paul Feyerabend so provocatively stated, “The church at the time of Galileo was much more faithful to reason than Galileo himself.”

At that time, Tycho Brahe’s modified geocentric theory of the planetary system (Mercury and Venus go around the sun, which goes around the earth), may have been a better bet given the evidence. Brahe’s theory is empirically indistinguishable from Copernicus’s. Venus goes through phases, like the moon, in Brahe’s model just as it does in Copernicus’s. No experiment or observation of Galileo could refute Brahe.

Here’s the rub. Galileo never mentions Brahe’s model once in Dialogue on the Two Chief World Systems. Galileo knew about Brahe. His title, Two Systems, seems simply a polemic device – at best a rhetorical ploy to eliminate his most worthy opponent by sleight of hand. He’d rather fight Ptolemy than Brahe.

Likewise, Galileo ignored Johannes Kepler in Dialogue. Kepler’s work (Astronomia Nova) was long established at the time Galileo wrote Dialogue. Kepler correctly identified that the planetary orbits were elliptical rather than circular, as Galileo thought. Kepler also modeled the tides correctly where Galileo got them wrong. Kepler wrote congratulatory letters to Galileo; Galileo’s responses were more reserved.

Galileo was probably a better man (or should have been) than his behavior toward Kepler and Brahe reveal. His fans fed his ego liberally, and he got carried away. Galileo, Brahe, Kepler and everyone else would have been better served by less aggrandizing and more humility. The tech press and the venture capital worlds that fuel what Vivek Wadhwa calls the myth of the 20-year old white male genius CEO should take note.

Moral Truths and True Beliefs

Posted by Bill Storage in Uncategorized on August 23, 2013

Suppose I’m about to flip a coin. Somehow you’re just certain it will be heads; you strongly believe so. I flip and you’e right. Say you’re right five times in a row. Can you claim rightness in any meaningful way, or did you merely hold a true belief on invalid grounds? What if you held a strong belief about a complex social issue with no personal knowledge of its details, but followed your community’s lead?

Were Democritus and Lucretius right in any meaningful way when they told the ancient Greeks and Romans that all matter was made up of “atoms” held together by forces, or did they merely hold true but unwarranted beliefs? Does George Berkeley deserve credit for getting quantum mechanics right in the 18th century?

It is moral truth that slavery is wrong and that women should not be subjugated, though this was once obvious to very few. Jesus, at least as he appears in the New Testament, misses every opportunity to condemn slavery. He tells us only not to beat them overly hard. And he tells slaves to obey their masters. Women fare only slightly better. Sometime between then and now the moral truth about women’s rights and slavery has been revealed. Has the moral truth about nuclear power been yet revealed? Solar power? GMO foods?

Last weekend while biking in the Marin Headlands I happened upon a group of unusual tourists. An old man with a long white beard wore high-wasted wool pants and a plain flannel shirt. His wife was in plain garb, clearly separating her from modern society, just as intended by Jakob Ammann, the tailor who inspired it. A younger man also wore a long beard, high wool pants and a plain shirt. I asked him if they were visiting and he said yes, from Ohio. I thought so, I said. He told me they were from Holmes County, naming a tiny town I knew from having grown up in Ohio. They were Amish, on tour in San Francisco.

We talked about the bay area’s curious summer weather, the Golden Gate Bridge and so on, I wished them a nice visit and rode out to Conzulman Road, where I stopped to add a jacket for the cold ride downhill. Two spandex clad local riders did the same. I overheard their snide condemnation of the “Mennonite” (they were Amish) religious zealots and their backward attitudes toward women and cosmology. The more I pondered this, the more it irked me. I think the I can explain why. With no more risk of unwarranted inference than that of my fellow San Franciscans about the Amish visitors, I can observe this about these socially-just bikers.

Get off your morally superior San Francisco high horses. The Amish visitors are far less wedded to dogma than you are. They have consciously broken with their clan and its rigid traditions in several visible ways; while you march straight down the party line. If your beliefs are less destructive to the environment, your cosmology more consistent with scientific evidence, and your position on women’s rights more enlightened than theirs, it is merely because of geography. You are fortunate that your community of influences have made more moral progress than theirs have. As it should be. Your community of influencers is larger and more educated. You can take no credit for your proximity to a better set of influencers. You hold your beliefs on purely social grounds, just like they do. But they examined their dogma and boldly took a few steps away from it – a mega-Rumspringa into a place that invites fellowship with lawlessness[1], where separation from the desires of the modern world[2] is not an option.

[1] Do not be unequally yoked together with unbelievers. For what fellowship has righteousness with lawlessness? And what communion has light with darkness? – 2 Corinthians 6:14

[2] And do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your mind, that you may prove what is that good and acceptable and perfect will of God. – Romans 12:2

Richard Rorty: A Matter for the Engineers

Posted by Bill Storage in Multidisciplinarians, Philosophy of Science on September 13, 2012

William Storage 13 Sep 2012

Visiting Scholar, UC Berkeley Science, Technology & Society Center

Richard Rorty (1931-2007) was arguably the most controversial philosopher in recent history. Unarguably, he was the most entertaining. Profoundly influenced by Thomas Kuhn, Rorty is fascinating and inspirational, even for engineers and scientists.

Richard Rorty (1931-2007) was arguably the most controversial philosopher in recent history. Unarguably, he was the most entertaining. Profoundly influenced by Thomas Kuhn, Rorty is fascinating and inspirational, even for engineers and scientists.

Rorty’s thought defied classification – literally; encyclopedias struggle to pin philosophical categories to him. He felt that confining yourself to a single category leads to personal stagnation on all levels. An interview excerpt at the end of this post ends with a casual yet weighty statement of his confidence in engineers’ ability to save the world.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Rorty looked at familiar things in different light – and could explain his position in plain English. I never found much of Heidegger to be coherent, let alone important. No such problem with Dick Rorty.

Rorty could simplify arcane philosophical concepts. He saw similarities where others saw differences, being mostly rejected by schools of thought he drew from. This was especially true for pragmatism. Often accused of hijacking this term, Rorty offered that pragmatism is a vague, ambiguous, and overworked word, but nonetheless, “it names the chief glory of our country’s intellectual tradition.” He was enamored with moral and scientific progress, and often glowed with optimism and hope while his contemporaries brooded in murky, nihilistic dungeons.

Richard Rorty photo by Mary Rorty. Used by permission.

Richard Rorty photo by Mary Rorty. Used by permission.

Rorty called himself a “Kuhnian” apart from those Kuhnians for whom The Structure of Scientific Revolution justified moral relativism and epistemic nihilism. Rorty’s critics in the hard sciences – at least those who embrace Kuhn – have gone to great lengths to distance Kuhn from Rorty. Philosophers have done the same, perhaps a bit sore from Rorty’s denigration of analytic philosophy and his insistence that philosophers have no special claim to wisdom. Kyle Cavagnini in the Spring 2012 issue of Stance (“Descriptions of Scientific Revolutions: Rorty’s Failure at Redescribing Scientific Progress”) finds that Rorty tries too hard to make Kuhn a relativist:

“Kuhn’s work provided a new framework in philosophy of science that garnered much attention, leading some of his theories to be adopted outside of the natural sciences. Unfortunately, some of these adoptions have not been faithful to Kuhn’s original theories, and at times just plain erroneous conclusions are drawn that use Kuhn as their justification. These misreadings not only detract from the power of Kuhn’s argument, but also serve to add false support for theories that Kuhn was very much against; Rorty was one such individual.”

Cavagnini may have some valid technical points. But it’s as easy to misread Rorty as to misread Kuhn. As I read Rorty, he derives from Kuhn that the authority of science has no basis beyond scientific consensus. It then follows for Rorty that instituational science and scientists have no basis for a privileged status in acquiring truth. Scientist who know their stuff shouldn’t disagree on this point. Rorty’s position is not cultural constructivism applied to science. He doesn’t remotely imply that one claim of truth – scientific or otherwise – is as good as another. In fact, Rorty explicitly argues against that position as applied to both science and ethics. Rorty then takes ideas he got from Kuhn to places that Kuhn would not have gone, without projecting his philosophical ideas onto Kuhn:

“To say that the study of the history of science, like the study of the rest of history, must be hermeneutical, and to deny (as I, but not Kuhn, would) that there is something extra called ‘rational reconstruction’ which can legitimize current scientific practice, is still not to say that the atoms, wave packages, etc., discovered by the physical scientists are creations of the human spirit.” – Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature

“I hope to convince the reader that the dialectic within analytical philosophy, which has carried … philosophy of science from Carnap to Kuhn, needs to be carried a few steps further.” – Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature

What Rorty calls “leveling down science” is aimed at the scientism of logical positivists in philosophy – those who try to “science-up” analytic philosophy:

“I tend to view natural science as in the business of controlling and predicting things, and as largely useless for philosophical purposes” – Rorty and Pragmatism: The Philosopher Responds to his Critics

For Rorty, both modern science and modern western ethics can claim superiority over their precursors and competitors. In other words, we are perfectly capable of judging that we’ve made moral and scientific progress without a need for a privileged position of any discipline, and without any basis beyond consensus. This line of thought enabled the political right to accuse Rorty of moral relativism and at the same time the left to accuse him of bigotry and ethnocentrism. Both did vigorously. [note]

You can get a taste of Rorty from the sound and video snippets available on the web, e.g. this clip where he dresses down the standard philosophical theory of truth with an argument that would thrill mathematician Kurt Gödel:

In his 2006 Dewey Lecture in Law and Philosophy at the University of Chicago, he explains his position, neither moral absolutist nor moral relativist (though accused of being both by different factions), in praise of western progress in science and ethics.

Another example of Rorty’s nuanced position is captured on tape in Stanford’s archives of the Entitled Opinions radio program. Host Robert Harrison is an eloquent scholar and announcer, but in a 2005 Entitled Opinions interview, Rorty frustrates Harrison to the point of being tongue-tied. At some point in the discussion Rorty offers that the rest of the world should become more like America. This strikes Harrison as perverse. Harrison asks for clarification, getting a response he finds even more perverse:

Harrison: What do you mean that the rest of the world should become a lot more like America? Would it be desirable to have all the various cultures across the globe Americanize? Would that not entail some sort of loss at least at the level of diversity or certain wisdoms that go back through their own particular traditions. What would be lost in the Americanization or Norwegianization of the world?

Rorty: A great deal would be lost. A great deal was lost when the Roman Empire suppressed a lot of native cultures. A great deal was lost when the Han Empire in China suppressed a lot of native cultures […]. Whenever there’s a rise in a great power a lot of great cultures get suppressed. That’s the price we pay for history.

Asked if this is not too high a price to pay, Rorty answers that if you could get American-style democracy around the globe, it would be a small price to have paid. Harrison is astounded, if not offended:

Harrison: Well here I’m going to speak in my own proper voice and to really disagree in this sense: that I think governments and forms of government are the result of a whole host of contingent geographical historical factors whereby western bourgeois liberalism or democracy arose through a whole set of circumstances that played themselves out over time, and I think that [there is in] America a certain set of presumptions that our form of democracy is infinitely exportable … [and] that we can just take this model of American democracy and make it work elsewhere. I think experience has shown us that it’s not that easy.

Rorty: We can’t make it work elsewhere but people coming to our country and finding out how things are done in the democratic west can go back and try to imitate that in their own countries. They’ve often done so with considerable success. I was very impressed on a visit to Guangzhou to see a replica of the statue of Liberty in one of the city parks. It was built by the first generation of Chinese students to visit America when they got back. They built a replica of the Statue of Liberty in order to help to try to explain to the other Chinese what was so great about the country they’d come back from. And remember that a replica of the Statue of Liberty was carried by the students in Tiananmen Square.

Harrison (agitated): Well OK but that’s one way. What if you… Why can’t we go to China and see a beautiful statue of the Buddha or something, and understand equally – have a moment of enlightenment and bring that statue back and say that we have something to learn from this other culture out there. And why is the statue of liberty the final transcend[ant] – you say yourself as a philosopher that you don’t – that there are no absolutes and that part of the misunderstanding in the history of philosophy is that there are no absolutes. It sounds like that for you the Statue of Liberty is an absolute.

Rorty: How about it’s the best thing anybody has come up with so far. It’s done more for humanity than the Buddha ever did. And it gives us something that … [interrupted]

Harrison: How can we know that!?

Rorty: From history.

Harrison: Well, for example, what do we know about the happiness of the Buddhist cultures from the inside? Can we really know from the outside that we’re happier than they are?

Rorty: I suspect so. We’ve all had experiences in moving around from culture to culture. They’re not closed off entities, opaque to outsiders. You can talk to people raised in lots of different places about how happy they are and what they’d like.

Then it spirals down a bit further. Harrison asks Rorty if he thinks capitalism is a neutral phenomenon. Rorty replies that capitalism is the worst system imaginable except for all the others that have been tried so far. He offers that communism, nationalization of production and state capitalism were utter disasters, adding that private property and private business are the only option left until some genius comes up with a new model.

Harrison then reveals his deep concern over the environment and the free market’s effect on it, suggesting that since the human story is now shown to be embedded in the world of nature, that philosophy might entertain the topic of “life” – specifically, progressing beyond 20th century humanist utopian values in light of climate change and resource usage. Rorty offers that unless we develop fusion energy or similar, we’ve had it just as much as if the terrorists get their hands on nuclear bombs. Rorty says human life and nature are valid concerns, but that he doesn’t see that they give any reason for philosophers to start talking about life, a topic he says philosophy has thus far failed to illuminate.

This irritates Harrison greatly. At one point he curtly addresses Rorty as “my dear Dick.” Rorty’s clarification, his apparent detachment, and his brevity seem to make things worse:

Rorty: “Well suppose that we find out that it’s all going to be wiped out by an asteroid. Would you want philosophers to suddenly start thinking about asteroids? We may well collapse due to the exhaustion of natural resources but what good is it going to do for philosophers to start thinking about natural resources?”

Harrison: “Yeah but Dick there’s a difference between thinking of asteroids, which is something that is outside of human control and which is not submitted to human decision and doesn’t enter into the political sphere, and talking about something which is completely under the governance of human action. I don’t say it’s under the governance of human will, but it is human action which is bringing about the asteroid, if you like. And therefore it’s not a question of waiting around for some kind of natural disaster to happen, because we are the disaster – or one could say that we are the disaster – and that the maximization of wealth for the maximum amount of people is exactly what is putting us on this track toward a disaster.

Rorty: Well, we’ve accommodated environmental change before. Maybe we can accommodate it again; maybe we can’t. But surely this is a matter for the engineers rather than the philosophers.

A matter for the engineers indeed.

.

————————————————-

.

Notes

1) Rorty and politics: The academic left cheered as Rorty shelled Ollie North’s run for the US Senate. As usual, not mincing words, Rorty called North a liar, a claim later repeated by Nancy Reagan. There was little cheering from the right when Rorty later had the academic left in his crosshairs; perhaps they failed to notice.. In 1997 Rorty wrote that the academic left must shed its anti-Americanism and its quest for even more abusive names for “The System.” “Outside the academy, Americans still want to feel patriotic,” observed Rorty. “They still want to feel part of a nation which can take control of its destiny and make itself a better place.”

On racism, Rorty observed that the left once promoted equality by saying we were all Americans, regardless of color. By contrast, he said, the contemporary left now “urges that America should not be a melting-pot, because we need to respect one another in our differences.” He chastised the academic left for destroying any hope for a sense of commonality by highlighting differences and preserving otherness. “National pride is to countries what self-respect is to individuals,” wrote Rorty.

For Dinesh D’Souza, patriotism is no substitute for religion. D’Souza still today seems obsessed with Rorty’s having once stated his intent “to arrange things so that students who enter as bigoted, homophobic religious fundamentalists will leave college with views more like our own.” This assault on Christianity lands Rorty on a D’Souza enemy list that includes Sam Harris, Christopher Hitchens, and Richard Dawkins, D’Souza apparently unaware that Rorty’s final understanding of pragmatism included an accomodation of liberal Christianity.

2) See Richard Rorty bibliographical material and photos maintained by the Rorty family on the Stanford web site.

Paul Feyerabend – The Worst Enemy of Science

Posted by Bill Storage in Philosophy of Science on August 7, 2012

Science, Holism and Easter

Posted by Bill Storage in Multidisciplinarians, Systems Thinking on April 8, 2012

Thomas E. Woods, Jr., in How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization, credits the church as being the primary sponsor of western science throughout most of the church’s existence. His point is valid, though many might find his presentation very economical with the truth. With a view that everything in the universe was interconnected, the church was content to ascribe the plague to sin. The church’s interest in science had something to do with Easter. I’ll get to that after a small diversion to relate this topic to one from a recent blog post.

Thomas E. Woods, Jr., in How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization, credits the church as being the primary sponsor of western science throughout most of the church’s existence. His point is valid, though many might find his presentation very economical with the truth. With a view that everything in the universe was interconnected, the church was content to ascribe the plague to sin. The church’s interest in science had something to do with Easter. I’ll get to that after a small diversion to relate this topic to one from a recent blog post.

Catholic theologians, right up until very recent times, have held a totally holistic view, seeing properties and attributes as belonging to high level objects and their context, and opposing reductionism and analysis by decomposition. In God’s universe (as they saw it), behavior of the parts was determined by the whole, not the other way around. Catholic holy men might well be seen as champions of “Systems Thinking” – at least in the popular modern use of that term. Like many systems thinking advocates in business and politics today, the church of the middle ages wasn’t merely pragmatic-anti-reductionist, it was philosophically anti-reductionist. I.e., their view was not that it is too difficult to analyze the inner workings of a thing to understand its properties, but that it is fundamentally impossible to do so.

Santa Maria degli Angeli, a Catholic solar observatory

Unlike modern anti-reductionists, whose movement has been from reductionism toward something variously called collectivism, pluralism or holism, the Vatican has been forced in the opposite direction. The Catholics were dragged kicking and screaming into the realm of reductionist science because one of their core values – throwing really big parties – demanded it.