Posts Tagged Thomas Kuhn

Grains of Truth: Science and Dietary Salt

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science, Philosophy of Science on June 29, 2025

Science doesn’t proceeds in straight lines. It meanders, collides, and battles over its big ideas. Thomas Kuhn’s view of science as cycles of settled consensus punctuated by disruptive challenges is a great way to understand this messiness, though later approaches, like Imre Lakatos’s structured research programs, Paul Feyerabend’s radical skepticism, and Bruno Latour’s focus on science’s social networks have added their worthwhile spins. This piece takes a light look, using Kuhn’s ideas with nudges from Feyerabend, Lakatos, and Latour, at the ongoing debate over dietary salt, a controversy that’s nuanced and long-lived. I’m not looking for “the truth” about salt, just watching science in real time.

Dietary Salt as a Kuhnian Case Study

The debate over salt’s role in blood pressure shows how science progresses, especially when viewed through the lens of Kuhn’s philosophy. It highlights the dynamics of shifting paradigms, consensus overreach, contrarian challenges, and the nonlinear, iterative path toward knowledge. This case reveals much about how science grapples with uncertainty, methodological complexity, and the interplay between evidence, belief, and rhetoric, even when relatively free from concerns about political and institutional influence.

In The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Kuhn proposed that science advances not steadily but through cycles of “normal science,” where a dominant paradigm shapes inquiry, and periods of crisis that can result in paradigm shifts. The salt–blood pressure debate, though not as dramatic in consequence as Einstein displacing Newton or as ideologically loaded as climate science, exemplifies these principles.

Normal Science and Consensus

Since the 1970s, medical authorities like the World Health Organization and the American Heart Association have endorsed the view that high sodium intake contributes to hypertension and thus increases cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk. This consensus stems from clinical trials such as the 2001 DASH-Sodium study, which demonstrated that reducing salt intake significantly (from 8 grams per day to 4) lowered blood pressure, especially among hypertensive individuals. This, in Kuhn’s view, is the dominant paradigm.

This framework – “less salt means better health” – has guided public health policies, including government dietary guidelines and initiatives like the UK’s salt reduction campaign. In Kuhnian terms, this is “normal science” at work. Researchers operate within an accepted model, refining it with meta-analyses and Randomized Control Trials, seeking data to reinforce it, and treating contradictory findings as anomalies or errors. Public health campaigns, like the AHA’s recommendation of less than 2.3 g/day of sodium, reflect this consensus. Governments’ involvement embodies institutional support.

Anomalies and Contrarian Challenges

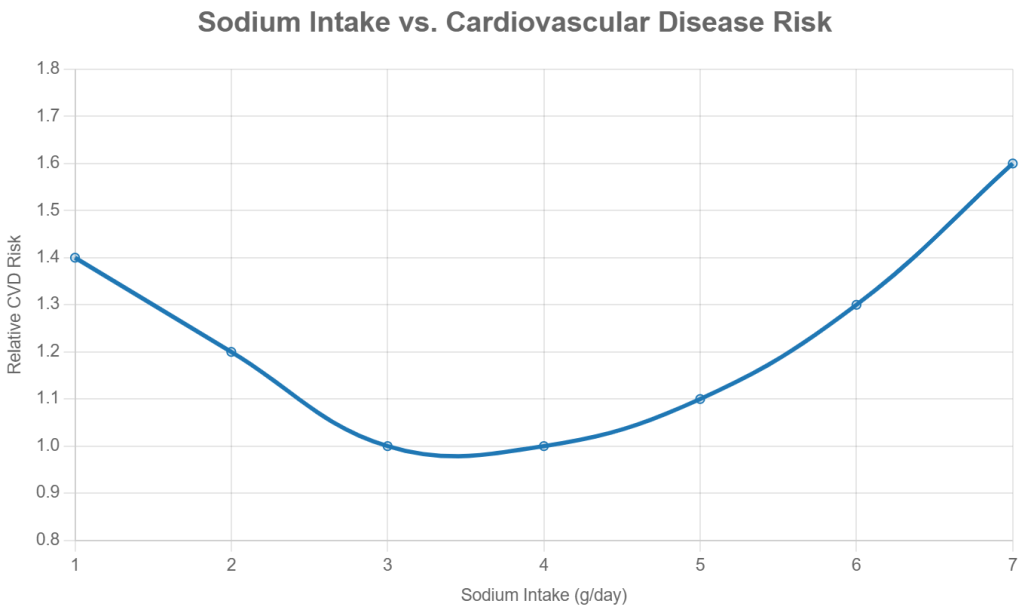

However, anomalies have emerged. For instance, a 2016 study by Mente et al. in The Lancet reported a U-shaped curve; both very low (less than 3 g/day) and very high (more than 5 g/day) sodium intakes appeared to be associated with increased CVD risk. This challenged the linear logic (“less salt, better health”) of the prevailing model. Although the differences in intake were not vast, the implications questioned whether current sodium guidelines were overly restrictive for people with normal blood pressure.

The video Salt & Blood Pressure: How Shady Science Sold America a Lie mirrors Galileo’s rhetorical flair, using provocative language such as “shady science” to challenge the establishment. Like Galileo’s defense of heliocentrism, contrarians in the salt debate (researchers like Mente) amplify anomalies to question dogma, sometimes exaggerating flaws in early studies (e.g., Lewis Dahl’s rat experiments) or alleging conspiracies (e.g., pharmaceutical influence). More in Feyerabend’s view than in Kuhn’s, this exaggeration and rhetoric might be desirable. It’s useful. It provides the challenges that the paradigm should be able to overcome to remain dominant.

These challenges haven’t led to a paradigm shift yet, as the consensus remains robust, supported by RCTs and global health data. But they highlight the Kuhnian tension between entrenched views and emerging evidence, pushing science to refine its understanding.

Framing the issue as a contrarian challenge might go something like this:

Evidence-based medicine sets treatment guidelines, but evidence-based medicine has not translated into evidence-based policy. Governments advise lowering salt intake, but that advice is supported by little robust evidence for the general population. Randomized controlled trials have not strongly supported the benefit of salt reduction for average people. Indeed, we see evidence that low salt might pose as great a risk.

Methodological Challenges

The question “Is salt bad for you?” is ill-posed. Evidence and reasoning say this question oversimplifies a complex issue: sodium’s effects vary by individual (e.g., salt sensitivity, genetics), diet (e.g., processed vs. whole foods), and context (e.g., baseline blood pressure, activity level). Science doesn’t deliver binary truths. Modern science gives probabilistic models, refined through iterative testing.

While randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have shown that reducing sodium intake can lower blood pressure, especially in sensitive groups, observational studies show that extremely low sodium is associated with poor health. This association may signal reverse causality, an error in reasoning. The data may simply reveal that sicker people eat less, not that they are harmed by low salt. This complexity reflects the limitations of study design and the challenges of isolating causal relationships in real-world populations. The above graph is a fairly typical dose-response curve for any nutrient.

The salt debate also underscores the inherent difficulty of studying diet and health. Total caloric intake, physical activity, genetic variation, and compliance all confound the relationship between sodium and health outcomes. Few studies look at salt intake as a fraction of body weight. If sodium recommendations were expressed as sodium density (mg/kcal), it might help accommodate individual energy needs and eating patterns more effectively.

Science as an Iterative Process

Despite flaws in early studies and the polemics of dissenters, the scientific communities continue to refine its understanding. For example, Japan’s national sodium reduction efforts since the 1970s have coincided with significant declines in stroke mortality, suggesting real-world benefits to moderation, even if the exact causal mechanisms remain complex.

Through a Kuhnian lens, we see a dominant paradigm shaped by institutional consensus and refined by accumulating evidence. But we also see the system’s limits: anomalies, confounding variables, and methodological disputes that resist easy resolution.

Contrarians, though sometimes rhetorically provocative or methodologically uneven, play a crucial role. Like the “puzzle-solvers” and “revolutionaries” in Kuhn’s model, they pressure the scientific establishment to reexamine assumptions and tighten methods. This isn’t a flaw in science; it’s the process at work.

Salt isn’t simply “good” or “bad.” The better scientific question is more conditional: How does salt affect different individuals, in which contexts, and through what mechanisms? Answering this requires humility, robust methodology, and the acceptance that progress usually comes in increments. Science moves forward not despite uncertainty, disputation and contradiction but because of them.

Anarchy and Its Discontents: Paul Feyerabend’s Critics

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science, Philosophy of Science on June 3, 2025

(For and against Against Method)

Paul Feyerabend’s 1975 Against Method and his related works made bold claims about the history of science, particularly the Galileo affair. He argued that science progressed not because of adherence to any specific method, but through what he called epistemological anarchism. He said that Galileo’s success was due in part to rhetoric, metaphor, and politics, not just evidence.

Some critics, especially physicists and historically rigorous philosophers of science, have pointed out technical and historical inaccuracies in Feyerabend’s treatment of physics. Here are some examples of the alleged errors and distortions:

Misunderstanding Inertial Frames in Galileo’s Defense of Copernicanism

Feyerabend argued that Galileo’s arguments for heliocentrism were not based on superior empirical evidence, and that Galileo used rhetorical tricks to win support. He claimed that Galileo simply lacked any means of distinguishing heliocentric from geocentric models empirically, so his arguments were no more rational than those of Tycho Brahe and other opponents.

His critics responded by saying that Galileo’s arguments based on the phases of Venus and Jupiter’s moons were empirically decisive against the Ptolemaic model. This is unarguable, though whether Galileo had empirical evidence to overthrow Tycho Brahe’s hybrid model is a much more nuanced matter.

Critics like Ronald Giere, John Worrall, and Alan Chalmers (What Is This Thing Called Science?) argued that Feyerabend underplayed how strong Galileo’s observational case actually was. They say Feyerabend confused the issue of whether Galileo had a conclusive argument with whether he had a better argument.

This warrants some unpacking. Specifically, what makes an argument – a model, a theory – better? Criteria might include:

- Empirical adequacy – Does the theory fit the data? (Bas van Fraassen)

- Simplicity – Does the theory avoid unnecessary complexity? (Carl Hempel)

- Coherence – Is it internally consistent? (Paul Thagard)

- Explanatory power – Does it explain more than rival theories? (Wesley Salmon)

- Predictive power – Does it generate testable predictions? (Karl Popper, Hempel)

- Fertility – Does it open new lines of research? (Lakatos)

Some argue that Galileo’s model (Copernicanism, heliocentrism) was obviously simpler than Brahe’s. But simplicity opens another can of philosophical worms. What counts as simple? Fewer entities? Fewer laws? More symmetry? Copernicus had simpler planetary order but required a moving Earth. And Copernicus still relied on epicycles, so heliocentrism wasn’t empirically simpler at first. Given the evidence of the time, a static Earth can be seen as simpler; you don’t need to explain the lack of wind and the “straight” path of falling bodies. Ultimately, this point boils down to aesthetics, not math or science. Galileo and later Newtonians valued mathematical elegance and unification. Aristotelians, the church, and Tychonians valued intuitive compatibility with observed motion.

Feyerabend also downplayed Galileo’s use of the principle of inertia, which was a major theoretical advance and central to explaining why we don’t feel the Earth’s motion.

Misuse of Optical Theory in the Case of Galileo’s Telescope

Feyerabend argued that Galileo’s use of the telescope was suspect because Galileo had no good optical theory and thus no firm epistemic ground for trusting what he saw.

His critics say that while Galileo didn’t have a fully developed geometrical optics theory (e.g., no wave theory of light), his empirical testing and calibration of the telescope were rigorous by the standards of the time.

Feyerabend is accused of anachronism – judging Galileo’s knowledge of optics by modern standards and therefore misrepresenting the robustness of his observational claims. Historians like Mario Biagioli and Stillman Drake point out that Galileo cross-verified telescope observations with the naked eye and used repetition, triangulation, and replication by others to build credibility.

Equating All Theories as Rhetorical Equals

Feyerabend in some parts of Against Method claimed that rival theories in the history of science were only judged superior in retrospect, and that even “inferior” theories like astrology or Aristotelian cosmology had equal rational footing at the time.

Historians like Steven Shapin (How to be Antiscientific) and David Wootton (The Invention of Science) say that this relativism erases real differences in how theories were judged even in Galileo’s time. While not elaborated in today’s language, Galileo and his rivals clearly saw predictive power, coherence, and observational support as fundamental criteria for choosing between theories.

Feyerabend’s polemical, theatrical tone often flattened the epistemic distinctions that working scientists and philosophers actually used, especially during the Scientific Revolution. His analysis of “anything goes” often ignored the actual disciplinary practices of science, especially in physics.

Failure to Grasp the Mathematical Structure of Physics

Scientists – those broad enough to know who Feyerabend was – often claim that he misunderstood or ignored the role of mathematics in theory-building, especially in Newtonian mechanics and post-Galilean developments. In Against Method, Feyerabend emphasizes metaphor and persuasion over mathematics. While this critique is valuable when aimed at the rhetorical and political sides of science, it underrates the internal mathematical constraints that shape physical theories, even for Galileo.

Imre Lakatos, his friend and critic, called Feyerabend’s work a form of “intellectual sabotage”, arguing that he distorted both the history and logic of physics.

Misrepresenting Quantum Mechanics

Feyerabend wrote about Bohr and Heisenberg in Philosophical Papers and later essays. Critics like Abner Shimony and Mario Bunge charge that Feyerabend misrepresented or misunderstood Bohr’s complementarity as relativistic, when Bohr’s position was more subtle and aimed at objective constraints on language and measurement.

Feyerabend certainly fails to understand the mathematical formalism underpinning Quantum Mechanics. This weakens his broader claims about theory incommensurability.

Feyerabend’s erroneous critique of Neil’s Bohr is seen in his 1958 Complimentarity:

“Bohr’s point of view may be introduced by saying that it is the exact opposite of [realism]. For Bohr the dual aspect of light and matter is not the deplorable consequence of the absence of a satisfactory theory, but a fundamental feature of the microscopic level. For him the existence of this feature indicates that we have to revise … the [realist] ideal of explanation.” (more on this in an upcoming post)

Epistemic Complaints

Beyond criticisms that he failed to grasp the relevant math and science, Feyerabend is accused of selectively reading or distorting historical episodes to fit the broader rhetorical point that science advances by breaking rules, and that no consistent method governs progress. Feyerabend’s claim that in science “anything goes” can be seen as epistemic relativism, leaving no rational basis to prefer one theory over another or to prefer science over astrology, myth, or pseudoscience.

Critics say Feyerabend blurred the distinction between how theories are argued (rhetoric) and how they are justified (epistemology). He is accused of conflating persuasive strategy with epistemic strength, thereby undermining the very principle of rational theory choice.

Some take this criticism to imply that methodological norms are the sole basis for theory choice. Feyerabend’s “anarchism” may demolish authority, but is anything left in its place except a vague appeal to democratic or cultural pluralism? Norman Levitt and Paul Gross, especially in Higher Superstition: The Academic Left and Its Quarrels with Science (1994), argue this point, along with saying Feyerabend attacked a caricature of science.

Personal note/commentary: In my view, Levitt and Gross did some great work, but Higher Superstition isn’t it. I bought the book shortly after its release because I was disgusted with weaponized academic anti-rationalism, postmodernism, relativism, and anti-science tendencies in the humanities, especially those that claimed to be scientific. I was sympathetic to Higher Superstition’s mission but, on reading it, was put off by its oversimplifications and lack of philosophical depth. Their arguments weren’t much better than those of the postmodernists. Critics of science in the humanities critics overreached and argued poorly, but they were responding to legitimate concerns in the philosophy of science. Specifically:

- Underdetermination – Two incompatible theories often fit the same data. Why do scientists prefer one over another? As Kuhn argued, social dynamics play a role.

- Theory-laden Observations – Observations are shaped by prior theory and assumptions, so science is not just “reading the book of nature.”

- Value-laden Theories – Public health metrics like life expectancy and morbidity (opposed to autonomy or quality of life) trickle into epidemiology.

- Historical Variability of Consensus – What’s considered rational or obvious changes over time (phlogiston, luminiferous ether, miasma theory).

- Institutional Interest and Incentives – String theory’s share of limited research funding, climate science in service of energy policy and social agenda.

- The Problem of Reification – IQ as a measure of intelligence has been reified in policy and education, despite deep theoretical and methodological debates about what it measures.

- Political or Ideological Capture – Marxist-Leninist science and eugenics were cases where ideology shaped what counted as science.

Higher Superstition and my unexpected negative reaction to it are what brought me to the discipline of History and Philosophy of Science.

Conclusion

Feyerabend exaggerated the uncertainty of early modern science, downplayed the empirical gains Galileo and others made, and misrepresented or misunderstood some of the technical content of physics. His mischievous rhetorical style made it hard to tell where serious argument ended and performance began. Rather than offering a coherent alternative methodology, Feyerabend’s value lay in exposing the fragility and contingency of scientific norms. He made it harder to treat methodological rules as timeless or universal by showing how easily they fracture under the pressure of real historical cases.

In a following post, I’ll review the last piece John Heilbron wrote before he died, Feyerabend, Bohr and Quantum Physics, which appeared in Stefano Gattei’s Feyerabend in Dialogue, a set of essays marking the 100th anniversary of Feyerabend’s birth.

Paul Feyerabend. Photo courtesy of Grazia Borrini-Feyerabend.

John Heilbron Interview – June 2012

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science, Philosophy of Science on June 2, 2025

In 2012, I spoke with John Heilbron, historian of science and Professor Emeritus at UC Berkeley, about his career, his work with Thomas Kuhn, and the legacy of The Structure of Scientific Revolutions on its 50th anniversary. We talked late into the night. The conversation covered his shift from physics to history, his encounters with Kuhn and Paul Feyerabend, and his critical take on the direction of Science and Technology Studies (STS).

The interview marked a key moment. Kuhn and Feyerabend’s legacies were under fresh scrutiny, and STS was in the midst of redefining itself, often leaning toward sociological frameworks at the expense of other approaches.

Thirteen years later, in 2025, this commentary revisits that interview to illuminate its historical context, situate Heilbron’s critiques, and explore their relevance to contemporary STS and broader academic debates.

Over more than a decade, I had ongoing conversations with Heilbron about the evolution of the history of science – history of the history of science – and the complex relationship between History of Science and Science, Technology, and Society (STS) programs. At UC Berkeley, unlike at Harvard or Stanford, STS has long remained a “Designated Emphasis” rather than a department or standalone degree. Academic conservatism in departmental structuring, concerns about reputational risk, and questions about the epistemic rigor of STS may all have contributed to this decision. Moreover, Berkeley already boasted world-class departments in both History and Sociology.

That 2012 interview, the only one we recorded, brought together themes we’d explored over many years. Since then, STS has moved closer to engaging with scientific content itself. But it still draws criticism, both from scientists and from public misunderstanding. In 2012, the field was still heavily influenced by sociological models, particularly the Strong Programme and social constructivism, which stressed how scientific knowledge is shaped by social context. One of the key texts in this tradition, Shapin and Schaffer’s Leviathan and the Air-Pump (1985), argued that even Boyle’s experiments weren’t simply about discovery but about constructing scientific consensus.

Heilbron pushed back against this framing. He believed it sidelined the technical and epistemic depth of science, reducing STS to a sociological critique. He was especially wary of the dense, abstract language common in constructivist work. In his view, it often served as cover for thin arguments, especially from younger scholars who copied the style but not the substance. He saw it as a tactic: establish control of the conversation by embedding a set of terms, then build influence from there.

The influence of Shapin and Schaffer, Heilbron argued, created the impression that STS was dominated by a single paradigm, ironically echoing the very Kuhnian framework they analyzed. His frustration with a then-recent Isis review reflected his concern that constructivism had become doctrinaire, pressuring scholars to conform to its methods even when irrelevant to their work. His reference to “political astuteness” pointed to the way in which key figures in the field successfully advanced their terminology and frameworks, gaining disproportionate influence. While this gave them intellectual clout, Heilbron saw it as a double-edged sword: it strengthened their position while encouraging dogmatism among followers who prioritized jargon over genuine analysis.

Bill Storage: How did you get started in this curious interdisciplinary academic realm?

John Heilbron: Well, it’s not really very interesting, but I was a graduate student in physics but my real interest was history. So at some point I went down to the History department and found the medievalist, because I wanted to do medieval history. I spoke with the medievalist ad he said, “well, that’s very charming but you know the country needs physicists and it doesn’t need medievalists, so why don’t you go back to physics.” Which I duly did. But he didn’t bother to point out that there was this guy Kuhn in the History department who had an entirely different take on the subject than he did. So finally I learned about Kuhn and went to see him. Since Kuhn had very few students, I looked good; and I gradually I worked my way free from the Physics department and went into history. My PhD is in History; and I took a lot history courses and, as I said, history really is my interest. I’m interested in science too of course but I feel that my major concerns are historical and the writing of history is to me much more interesting and pleasant than calculations.

You entered that world at a fascinating time, when history of science – I’m sure to the surprise of most of its scholars – exploded onto the popular scene. Kuhn, Popper, Feyerabend and Lakatos suddenly appeared in The New Yorker, Life Magazine, and The Christian Century. I find that these guys are still being read, misread and misunderstood by many audiences. And that seems to be true even for their intended audiences – sometimes by philosophers and historians of science – certainly by scientists. I see multiple conflicting readings that would seem to show that at least some of them are wrong.

Well if you have two or more different readings then I guess that’s a safe conclusion. (Laughs.)

You have a problem with multiple conflicting truths…? Anyway – misreading Kuhn…

I’m more familiar with the misreading of Kuhn than of the others. I’m familiar with that because he was himself very distressed by many of the uses made of his work – particularly the notion that science is no different from art or has no stronger basis than opinion. And that bothered him a lot.

I don’t know your involvement in his work around that time. Can you tell me how you relate to what he was doing in that era?

I got my PhD under him. In fact my first work with him was hunting up footnotes for Structure. So I knew the text of the final draft well – and I knew him quite well during the initial reception of it. And then we all went off together to Copenhagen for a physics project and we were all thrown together a lot. So that was my personal connection and then of course I’ve been interested subsequently in Structure, as everybody is bound to be in my line of work. So there’s no doubt, as he says so in several places, that he was distressed by the uses made of it. And that includes uses made in the history of science particularly by the social constructionists, who try to do without science altogether or rather just to make it epiphenomenal on political or social forces.

I’ve read opinions by others who were connected with Kuhn saying there was a degree of back-peddling going by Kuhn in the 1970s. The implication there is that he really did intend more sociological commentary than he later claimed. Now I don’t see evidence of that in the text of Structure, and incidents like his telling Freeman Dyson that he (Kuhn) was not a Kuhnian would suggest otherwise. Do you have any thoughts on that?

I think that one should keep in mind the purpose of Structure, or rather the context in which it was produced. It was supposed to have been an article in this encyclopedia of unified science and Kuhn’s main interest was in correcting philosophers. He was not aiming for historians even. His message was that the philosophy practiced by a lot of positivists and their description of science was ridiculous because it didn’t pay any attention to the way science was actually done. So Kuhn was going to tell them how science was done, in order to correct philosophy. But then much to his surprise he got picked up by people for whom it was not written, who derived from it the social constructionist lesson that we’re all familiar with. And that’s why he was an unexpected rebel. But he did expect to be rebellious; that was the whole point. It’s just that the object of his rebellion was not history or science but philosophy.

So in that sense it would seem that Feyerabend’s question on whether Kuhn intended to be prescriptive versus descriptive is answered. It was not prescriptive.

Right – not prescriptive to scientists. But it was meant to be prescriptive to the philosophers – or at least normalizing – so that they would stop being silly and would base their conception of scientific progress on the way in which scientists actually went about their business. But then the whole thing got too big for him and he got into things that, in my opinion, really don’t have anything to do with his main argument. For example, the notion of incommensurability, which was not, it seems to me, in the original program. And it’s a logical construct that I don’t think is really very helpful, and he got quite hung up on that and seemed to regard that as the most important philosophical message from Structure.

I wasn’t aware that he saw it that way. I’m aware that quite a few others viewed it like that. Paul Feyerabend, in one of his last books, said that he and Kuhn kicked around this idea of commensurability in 1960 and had slightly different ideas about where to go with it. Feyerabend said Kuhn wanted to use it historically whereas his usage was much more abstract. I was surprised at the level of collaboration indicated by Feyerabend.

Well they talked a lot. They were colleagues. I remember parties at Kuhn’s house where Feyerabend would show up with his old white T shirt and several women – but that’s perhaps irrelevant to the main discussion. They were good friends. I got along quite well with Feyerabend too. We had discussions about the history of quantum physics and so on. The published correspondence between Feyerabend and Lakatos is relevant here. It’s rather interesting in that the person we’ve left out of the discussion so far, Karl Popper, was really the lighthouse for Feyerabend and Lakatos, but not for Kuhn. And I think that anybody who wants to get to the bottom of the relationship between Kuhn and Feyerabend needs to consider the guy out of the frame, who is Popper.

It appears Feyerabend was very critical of Kuhn and Structure at the time it was published. I think at that point Feyerabend was still essentially a Popperian. It seems Feyerabend reversed position on that over the next decade or so.

JH: Yes, at the time in question, around 1960, when they had these discussions, I think Feyerabend was still very much in Popper’s camp. Of course like any bright student, he disagreed with his professor about things.

How about you, as a bright student in 1960 – what did you disagree with your professor, Kuhn, about?

Well I believe in the proposition that philosophers and historians have different metabolisms. And I’m metabolically a historian and Kuhn was metabolically a philosopher – even though he did write history. But his most sustained piece of history of science was his book on black body theory; and that’s very narrowly intellectualist in approach. It’s got nothing to do with the themes of the structure of scientific revolutions – which does have something to say for the historian – but he was not by practice a historian. He didn’t like a whole lot of contingent facts. He didn’t like archival and library work. His notion of fun was take a few texts and just analyze and reanalyze them until he felt he had worked his way into the mind of their author. I take that to be a necromantic feat that’s not really possible.

I found that he was a very clever guy and he was excellent as a professor because he was very interested in what you were doing as soon it was something he thought he could make some use of. And that gave you the idea that you were engaged in something important, so I must give him that. On the other hand he just didn’t have the instincts or the knowledge to be a historian and so I found myself not taking much from his own examples. Once I had an argument with him about some way of treating a historical subject and I didn’t feel that I got anything out of him. Quite the contrary; I thought that he just ducked all the interesting issues. But that was because they didn’t concern him.

James Conant, president of Harvard who banned communists, chair of the National Science Foundation, etc.: how about Conant’s influence on Structure?

It’s not just Conant. It was the whole Harvard circle, of which Kuhn was part. There was this guy, Leonard Nash; there was Gerald Holton. And these guys would get together and l talk about various things having to do with the relationship between science and the public sphere. It was a time when Conant was fighting for the National Science Foundation and I think that this notion of “normal science” in which the scientists themselves must be left fully in charge of what they’re doing in order to maximize the progress within the paradigm to bring the profession swiftly to the next revolution – that this is essentially the Conant doctrine with respect to the ground rules of the National Science Foundation, which is “let the scientists run it.” So all those things were discussed. And you can find many bits of Kuhn’s Structure in that discussion. For example, the orthodoxy of normal science in, say, Bernard Cohen, who didn’t make anything of it of course. So there’s a lot of this Harvard group in Structure, as well as certain lessons that Kuhn took from his book on the Copernican Revolution, which was the textbook for the course he gave under Conant. So yes, I think Conant’s influence is very strong there.

So Kuhn was ultimately a philosopher where you are a historian. I think I once heard you say that reading historical documents does not give you history.

Well I agree with that, but I don’t remember that I was clever enough to say it.

Assuming you said it or believe it, then what does give you history?

Well, reading them is essential, but the part contributed by the historian is to make some sense of all the waste paper he’s been reading. This is essentially a construction. And that’s where the art, the science, the technique of the historian comes into play, to try to make a plausible narrative that has to satisfy certain rules. It can’t go against the known facts and it can’t ignore the new facts that have come to light through the study of this waste paper, and it can’t violate rules of verisimilitude, human action and whatnot. But otherwise it’s a construction and you’re free to manipulate your characters, and that’s what I like about it.

So I take it that’s where the historian’s metabolism comes into play – avoidance of leaping to conclusions with the facts.

True, but at some point you’ve got to make up a story about those facts.

Ok, I’ve got a couple questions on the present state of affairs – and this is still related to the aftermath of Kuhn. From attending colloquia, I sense that STS is nearly a euphemism for sociology of science. That bothers me a bit, possibly because I’m interested in the intersection of science, technology and society. Looking at the core STS requirements on Stanford’s website, I see few courses listed that would give a student any hint of what science looks like from the inside.

I’m afraid you’re only too right. I’ve got nothing against sociology of science, the study of scientific institutions, etc. They’re all very good. But they’re tending to leave the science out, and in my opinion, the further they get from science, the worse their arguments become. That’s what bothers me perhaps most of all – the weakness of the evidentiary base of many of the arguments and conclusions that are put forward.

I thought we all learned a bit from the Science Wars – thought that sort of indeterminacy of meaning and obfuscatory language was behind us. Either it’s back, or it never went away.

Yeah, the language part is an important aspect of it, and even when the language is relatively comprehensible as I think it is in, say, constructivist history of science – by which I mean the school of Schaffer and Shapin – the insistence on peculiar argot becomes a substitute for thought. You see it quite frequently in people less able than those two guys are, who try to follow in their footsteps. You get words strung together supposedly constituting an argument but which in fact don’t. I find that quite an interesting aspect of the business, and very astute politically on the part of those guys because if you can get your words into the discourse, why, you can still hope to have influence. There’s a doctrinaire aspect to it. I was just reading the current ISIS favorable book review by one of the fellow travelers of this group. The book was not written by one of them. The review was rather complimentary but then at the end says it is a shame that this author did not discuss her views as related to Schaffer and Shapin. Well, why the devil should she? So, yes, there’s issues of language, authority, and poor argumentation. STS is afflicted by this, no doubt.

Extraordinary Popular Miscarriages of Science, Part 6 – String Theory

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science, Philosophy of Science on May 3, 2025

Introduction: A Historical Lens on String Theory

In 2006, I met John Heilbron, widely credited with turning the history of science from an emerging idea into a professional academic discipline. While James Conant and Thomas Kuhn laid the intellectual groundwork, it was Heilbron who helped build the institutions and frameworks that gave the field its shape. Through John I came to see that the history of science is not about names and dates – it’s about how scientific ideas develop, and why. It explores how science is both shaped by and shapes its cultural, social, and philosophical contexts. Science progresses not in isolation but as part of a larger human story.

The “discovery” of oxygen illustrates this beautifully. In the 18th century, Joseph Priestley, working within the phlogiston theory, isolated a gas he called “dephlogisticated air.” Antoine Lavoisier, using a different conceptual lens, reinterpreted it as a new element – oxygen – ushering in modern chemistry. This was not just a change in data, but in worldview.

When I met John, Lee Smolin’s The Trouble with Physics had just been published. Smolin, a physicist, critiques string theory not from outside science but from within its theoretical tensions. Smolin’s concerns echoed what I was learning from the history of science: that scientific revolutions often involve institutional inertia, conceptual blind spots, and sociopolitical entanglements.

My interest in string theory wasn’t about the physics. It became a test case for studying how scientific authority is built, challenged, and sustained. What follows is a distillation of 18 years of notes – string theory seen not from the lab bench, but from a historian’s desk.

A Brief History of String Theory

Despite its name, string theory is more accurately described as a theoretical framework – a collection of ideas that might one day lead to testable scientific theories. This alone is not a mark against it; many scientific developments begin as frameworks. Whether we call it a theory or a framework, it remains subject to a crucial question: does it offer useful models or testable predictions – or is it likely to in the foreseeable future?

String theory originated as an attempt to understand the strong nuclear force. In 1968, Gabriele Veneziano introduced a mathematical formula – the Veneziano amplitude – to describe the scattering of strongly interacting particles such as protons and neutrons. By 1970, Pierre Ramond incorporated supersymmetry into this approach, giving rise to superstrings that could account for both fermions and bosons. In 1974, Joël Scherk and John Schwarz discovered that the theory predicted a massless spin-2 particle with the properties of the hypothetical graviton. This led them to propose string theory not as a theory of the strong force, but as a potential theory of quantum gravity – a candidate “theory of everything.”

Around the same time, however, quantum chromodynamics (QCD) successfully explained the strong force via quarks and gluons, rendering the original goal of string theory obsolete. Interest in string theory waned, especially given its dependence on unobservable extra dimensions and lack of empirical confirmation.

That changed in 1984 when Michael Green and John Schwarz demonstrated that superstring theory could be anomaly-free in ten dimensions, reviving interest in its potential to unify all fundamental forces and particles. Researchers soon identified five mathematically consistent versions of superstring theory.

To reconcile ten-dimensional theory with the four-dimensional spacetime we observe, physicists proposed that the extra six dimensions are “compactified” into extremely small, curled-up spaces – typically represented as Calabi-Yau manifolds. This compactification allegedly explains why we don’t observe the extra dimensions.

In 1995, Edward Witten introduced M-theory, showing that the five superstring theories were different limits of a single 11-dimensional theory. By the early 2000s, researchers like Leonard Susskind and Shamit Kachru began exploring the so-called “string landscape” – a space of perhaps 10^500 (1 followed by 500 zeros) possible vacuum states, each corresponding to a different compactification scheme. This introduced serious concerns about underdetermination – the idea that available empirical evidence cannot determine which among many competing theories is correct.

Compactification introduces its own set of philosophical problems. Critics Lee Smolin and Peter Woit argue that compactification is not a prediction but a speculative rationalization: a move designed to save a theory rather than derive consequences from it. The enormous number of possible compactifications (each yielding different physics) makes string theory’s predictive power virtually nonexistent. The related challenge of moduli stabilization – specifying the size and shape of the compact dimensions – remains unresolved.

Despite these issues, string theory has influenced fields beyond high-energy physics. It has informed work in cosmology (e.g., inflation and the cosmic microwave background), condensed matter physics, and mathematics (notably algebraic geometry and topology). How deep and productive these connections run is difficult to assess without domain-specific expertise that I don’t have. String theory has, in any case, produced impressive mathematics. But mathematical fertility is not the same as scientific validity.

The Landscape Problem

Perhaps the most formidable challenge string theory faces is the landscape problem: the theory allows for an enormous number of solutions – on the order of 10^500. Each solution represents a possible universe, or “vacuum,” with its own physical constants and laws.

Why so many possibilities? The extra six dimensions required by string theory can be compactified in myriad ways. Each compactification, combined with possible energy configurations (called fluxes), gives rise to a distinct vacuum. This extreme flexibility means string theory can, in principle, accommodate nearly any observation. But this comes at the cost of predictive power.

Critics argue that if theorists can forever adjust the theory to match observations by choosing the right vacuum, the theory becomes unfalsifiable. On this view, string theory looks more like metaphysics than physics.

Some theorists respond by embracing the multiverse interpretation: all these vacua are real, and our universe is just one among many. The specific conditions we observe are then attributed to anthropic selection – we could only observe a universe that permits life like us. This view aligns with certain cosmological theories, such as eternal inflation, in which different regions of space settle into different vacua. But eternal inflation can exist independent of string theory, and none of this has been experimentally confirmed.

The Problem of Dominance

Since the 1980s, string theory has become a dominant force in theoretical physics. Major research groups at Harvard, Princeton, and Stanford focus heavily on it. Funding and institutional prestige have followed. Prominent figures like Brian Greene have elevated its public profile, helping transform it into both a scientific and cultural phenomenon.

This dominance raises concerns. Critics such as Smolin and Woit argue that string theory has crowded out alternative approaches like loop quantum gravity or causal dynamical triangulations. These alternatives receive less funding and institutional support, despite offering potentially fruitful lines of inquiry.

In The Trouble with Physics, Smolin describes a research culture in which dissent is subtly discouraged and young physicists feel pressure to align with the mainstream. He worries that this suppresses creativity and slows progress.

Estimates suggest that between 1,000 and 5,000 researchers work on string theory globally – a significant share of theoretical physics resources. Reliable numbers are hard to pin down.

Defenders of string theory argue that it has earned its prominence. They note that theoretical work is relatively inexpensive compared to experimental research, and that string theory remains the most developed candidate for unification. Still, the issue of how science sets its priorities – how it chooses what to fund, pursue, and elevate – remains contentious.

Wolfgang Lerche of CERN once called string theory “the Stanford propaganda machine working at its fullest.” As with climate science, 97% of string theorists agree that they don’t want to be defunded.

Thomas Kuhn’s Perspective

The logical positivists and Karl Popper would almost certainly dismiss string theory as unscientific due to its lack of empirical testability and falsifiability – core criteria in their respective philosophies of science. Thomas Kuhn would offer a more nuanced interpretation. He wouldn’t label string theory unscientific outright, but would express concern over its dominance and the marginalization of alternative approaches. In Kuhn’s framework, such conditions resemble the entrenchment of a paradigm during periods of normal science, potentially at the expense of innovation.

Some argue that string theory fits Kuhn’s model of a new paradigm, one that seeks to unify quantum mechanics and general relativity – two pillars of modern physics that remain fundamentally incompatible at high energies. Yet string theory has not brought about a Kuhnian revolution. It has not displaced existing paradigms, and its mathematical formalism is often incommensurable with traditional particle physics. From a Kuhnian perspective, the landscape problem may be seen as a growing accumulation of anomalies. But a paradigm shift requires a viable alternative – and none has yet emerged.

Lakatos and the Degenerating Research Program

Imre Lakatos offered a different lens, seeing science as a series of research programs characterized by a “hard core” of central assumptions and a “protective belt” of auxiliary hypotheses. A program is progressive if it predicts novel facts; it is degenerating if it resorts to ad hoc modifications to preserve the core.

For Lakatos, string theory’s hard core would be the idea that all particles are vibrating strings and that the theory unifies all fundamental forces. The protective belt would include compactification schemes, flux choices, and moduli stabilization – all adjusted to fit observations.

Critics like Sabine Hossenfelder argue that string theory is a degenerating research program: it absorbs anomalies without generating new, testable predictions. Others note that it is progressive in the Lakatosian sense because it has led to advances in mathematics and provided insights into quantum gravity. Historians of science are divided. Johansson and Matsubara (2011) argue that Lakatos would likely judge it degenerating; Cristin Chall (2019) offers a compelling counterpoint.

Perhaps string theory is progressive in mathematics but degenerating in physics.

The Feyerabend Bomb

Paul Feyerabend, who Lee Smolin knew from his time at Harvard, was the iconoclast of 20th-century philosophy of science. Feyerabend would likely have dismissed string theory as a dogmatic, aesthetic fantasy. He might write something like:

“String theory dazzles with equations and lulls physics into a trance. It’s a mathematical cathedral built in the sky, a triumph of elegance over experience. Science flourishes in rebellion. Fund the heretics.”

Even if this caricature overshoots, Feyerabend’s tools offer a powerful critique:

- Untestability: String theory’s predictions remain out of reach. Its core claims – extra dimensions, compactification, vibrational modes – cannot be tested with current or even foreseeable technology. Feyerabend challenged the privileging of untested theories (e.g., Copernicanism in its early days) over empirically grounded alternatives.

- Monopoly and suppression: String theory dominates intellectual and institutional space, crowding out alternatives. Eric Weinstein recently said, in Feyerabendian tones, “its dominance is unjustified and has resulted in a culture that has stifled critique, alternative views, and ultimately has damaged theoretical physics at a catastrophic level.”

- Methodological rigidity: Progress in string theory is often judged by mathematical consistency rather than by empirical verification – an approach reminiscent of scholasticism. Feyerabend would point to Johannes Kepler’s early attempt to explain planetary orbits using a purely geometric model based on the five Platonic solids. Kepler devoted 17 years to this elegant framework before abandoning it when observational data proved it wrong.

- Sociocultural dynamics: The dominance of string theory stems less from empirical success than from the influence and charisma of prominent advocates. Figures like Brian Greene, with their public appeal and institutional clout, help secure funding and shape the narrative – effectively sustaining the theory’s privileged position within the field.

- Epistemological overreach: The quest for a “theory of everything” may be misguided. Feyerabend would favor many smaller, diverse theories over a single grand narrative.

Historical Comparisons

Proponents say other landmark theories emerging from math predated their experimental confirmation. They compare string theory to historical cases. Examples include:

- Planet Neptune: Predicted by Urbain Le Verrier based on irregularities in Uranus’s orbit, observed in 1846.

- General Relativity: Einstein predicted the bending of light by gravity in 1915, confirmed by Arthur Eddington’s 1919 solar eclipse measurements.

- Higgs Boson: Predicted by the Standard Model in the 1960s, observed at the Large Hadron Collider in 2012.

- Black Holes: Predicted by general relativity, first direct evidence from gravitational waves observed in 2015.

- Cosmic Microwave Background: Predicted by the Big Bang theory (1922), discovered in 1965.

- Gravitational Waves: Predicted by general relativity, detected in 2015 by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO).

But these examples differ in kind. Their predictions were always testable in principle and ultimately tested. String theory, in contrast, operates at the Planck scale (~10^19 GeV), far beyond what current or foreseeable experiments can reach.

Special Concern Over Compactification

A concern I have not seen discussed elsewhere – even among critics like Smolin or Woit – is the epistemological status of compactification itself. Would the idea ever have arisen apart from the need to reconcile string theory’s ten dimensions with the four-dimensional spacetime we experience?

Compactification appears ad hoc, lacking grounding in physical intuition. It asserts that dimensions themselves can be small and curled – yet concepts like “small” and “curled” are defined within dimensions, not of them. Saying a dimension is small is like saying that time – not a moment in time, but time itself – can be “soon” or short in duration. It misapplies the very conceptual framework through which such properties are understood. At best, it’s a strained metaphor; at worst, it’s a category mistake and conceptual error.

This conceptual inversion reflects a logical gulf that proponents overlook or ignore. They say compactification is a mathematical consequence of the theory, not a contrivance. But without grounding in physical intuition – a deeper concern than empirical support – compactification remains a fix, not a forecast.

Conclusion

String theory may well contain a correct theory of fundamental physics. But without any plausible route to identifying it, string theory as practiced is bad science. It absorbs talent and resources, marginalizes dissent, and stifles alternative research programs. It is extraordinarily popular – and a miscarriage of science.

Extraordinary Popular Miscarriages of Science, Part 5 – Climate Science

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science on April 6, 2025

NASA reports that ninety-seven percent of climate scientists agree that human-caused climate change is happening.

As with earlier posts on popular miscarriages of science, I look at climate science through the lens of the 20th century historians of science and philosophers of science and conclude that climate science is epistemically thin.

To elaborate a bit, most sensible folk accept that climate science addresses a potentially critical concern and that it has many earnest and talented practitioners. Despite those practitioners, it can be critiqued as bad science. We can do that without delving into the levels or claims, disputations, and counterarguments on relationships between ice cores, CO₂ concentrations and temperature. We can instead use the perspectives of prominent historians and philosophers of science of the 20th century, including the Logical Positivists in general, positivist Carl Hempel in particular, Karl Popper, Thomas Kuhn, Imre Lakatos, and Paul Feyerabend. Each perspective offers a distinct philosophical lens that highlights shortcomings in climate science’s methodologies and practices. I’ll explain each of those perspectives, why I think they’re important, and I’ll explore the critiques they would likely advance. These critiques don’t invalidate climate science conceptually as a field of inquiry but they highlight serious logical and philosophical concerns about its methodologies, practices, and epistemic foundations.

The historians and philosophers invoked here were fundamentally concerned with the demarcation problem: how to differentiate good science, bad science, and pseudoscience using a methodological perspective. They didn’t necessarily agree with each other. In some cases, like Kuhn versus Popper, they outright despised each other. All were flawed, but they were giants who shone brightly and presented systematic visions of how science works and what good science is.

Carnap, Ayer and the Positivists: Verification

The early Logical Positivists, particularly Rudolf Carnap and A.J. Ayer, saw empirical verification as the cornerstone of scientific claims. To be meaningful, a claim must be testable through observation or experiment. Climate science, while rooted in empirical data, struggles with verifiability because of its focus on long-term, global phenomena. Predictions about future consequences like sea level change, crop yield, hurricane frequency, and average temperature are not easily verifiable within a human lifespan or with current empirical methods. That might merely suggest that climate science is hard, not that it is bad. But decades of past predictions and retrodictions have been notoriously poor. Consequently, theories have been continuously revised in light of failed predictions. The reliance on indirect evidence – proxy data and computer simulations – rather than controlled experiments (which would be impossible or unethical) would not satisfy the positivists’ demand for direct, observable confirmation. Climatologist Michael Mann (originator of the “hockey stick” graph) often refers to climate simulation results as data. It is not – not in any sense that a positivist would use the term data. Positivists would see these difficulties and predictive failures as falling short of their strict criteria for scientific legitimacy.

Carl Hempel: Absence of Appeal to Universal Laws

The philosophy of Carl Hempel centered on the deductive-nomological model (aka covering-law model), which holds that scientific explanations should be derived from universal, timeless laws of nature combined with deductive logic about specific sense observations (empirical data). For Hempel, explanation and prediction were two sides of the same coin. If you can’t predict, then you cannot explain. For Hempel to judge a scientific explanation valid, deductive logic applied to laws of nature must confer nomic expectability upon the phenomenon being explained.

Climate science rarely operates with the kinds of laws of nature Hempel considered suitably general, simple, and verifiable. Instead, it relies on statistical correlations and computer models such as linking CO₂ concentrations to temperature increases through statistical trends, rather than strict, law-like statements. These approaches contrast with Hempel’s ideal of deductive certifiability. Scientific explanations should, by Hempel’s lights, be structured as deductive arguments, where the truth of the premises (law of nature plus initial conditions plus empirical data) entails the truth of the phenomenon to be explained. Without universal laws to anchor its explanations, climate science would appear to Hempel to lack the logical rigor of good science. On Hempel’s view, climate science’s dependence on complex models having parameters that are constantly re-tuned further weakens its explanatory power.

Hempel’s deductive-nomological model was a solid effort at removing causality from scientific explanations, something the positivists, following David Hume, thought to be too metaphysical. The deductive-nomological model ultimately proved unable to bear the load Hempel wanted it to carry. Scientific explanation doesn’t work in certain cases without appeal to the notion of causality. That failure of Hempel’s model doesn’t weaken its criticism of climate science, or criticism of any other theory, however. It merely limits the deductive-nomological model’s ability to defend a theory by validating its explanations.

Karl Popper: Falsifiability

Karl Popper’s central criterion for demarcating good science from bad science and pseudoscience is falsifiability. A scientific theory, in his view, must make risky predictions that can be tested and potentially proven false. If a theory could not in principle be falsified, it does not belong to the realm of science.

The predictive models of climate science face severe challenges under this criterion. Climate models often project long-term trends, typically, global temperature increases over decades or centuries, which are probabilistic and difficult to test. Shorter-term, climate science has made abundant falsifiable predictions that were in fact falsified. Popper would initially see this as a mark of bad science, rather than pseudoscience.

But climate scientists have frequently adjusted their models or invoked external factors like previously unknown aerosol concentrations or volcanic eruptions to explain discrepancies. This would make climate science look, to Popper, too much like scientific Marxism and psychoanalysis, both of which he condemned for accommodating all possible outcomes to a prediction. When global temperatures temporarily stabilize or decrease, climate scientists often argue that natural variability is masking a long-term trend, rather than conceding a flaw in the theory. On this point, Popper would see climate science more akin to pseudoscience, since it lacks clear, testable predictions that could definitively refute its core claims.

For Popper, climate science must vigorously court skepticism and invite attempts at disputation and refutation, especially from dissenting insiders like Tol, Curry, and Michaels (more on below). Instead, climate science brands them as traitors.

Thomas Kuhn: Paradigm Rigidity

Thomas Kuhn agreed that Popper’s notion of falsifiability was how scientists think they behave, eager to subject their theories to disconfirmation. But scientific institutions don’t behave like that. Kuhn described science as progressing through paradigms, the frameworks, shared within a scientific community, that define normal scientific practice, periodically interrupted by revolutionary shifts, with a new theory displacing an older one.

A popular criticism of climate science is that science is not based on consensus. Kuhn would disagree, arguing that all scientific paradigms are fundamentally consensus-based.

“Normal science” for Kuhn was the state of things in a paradigm where most activity is aimed at defending the paradigm, thereby rationalizing the rejection of any evidence that disconfirms its theories. In this sense, everyday lab-coat scientists are some of the least scientific of professionals.

“Even in physics,” wrote Kuhn, “there is no standard higher than the assent of the relevant community.” So for Kuhn, evidence does not completely speak for itself, since assent about what evidence exists (Is that blip on the chart a Higgs boson or isn’t it?) must exist within the community for a theory to show consistency with observation. Climate science, more than any current paradigm except possibly string theory, has built high walls around its dominant theory.

That theory is the judgement, conclusion, or belief that human activity, particularly CO₂ emissions, has driven climate change for 150 years and will do so at an accelerated pace in the future. The paradigm virtually ensures that the vast majority of climate scientists agree with the theory because the theory is the heart of the paradigm, as Kuhn would see it. Within a paradigm, Kuhn accepts the role of consensus, but he wants outsiders to be able to overthrow the paradigm.

Given the relevant community’s insularity, Kuhn would see climate scientists’ claim that the anthropogenic warming theory is consistent with all their data as a case of anomalies being rationalized to preserve the paradigm. He would point to Michael Mann’s resistance to disclose his hockey stick data and simulation code as brutal shielding of the paradigm, regardless of Mann’s being found innocent of ethics violations.

Climate science’s tendency to dismiss solar influence and alternative hypotheses would likely be interpreted by Kuhn as the marginalization of dissent and paradigm rigidity. Kuhn might not see this rigidity as a sign of dishonesty or interest – as Paul Feyerabend (below) would – but would see the prevailing framework as stifling the revolutionary thinking he believed necessary for scientific advancement. From Kuhn’s perspective, climate science’s entrenched consensus could make it deeply flawed by prioritizing conformity too heavily over innovation.

Imre Lakatos: Climate as “Research Programme”

Lakatos developed his concept of “research programmes” to evaluate scientific progress. He blended ideas from Popper’s falsification and Kuhn’s paradigm shifts. Lakatos distinguished between progressive and degenerating research programs based on their ability to predict new facts and handle challenges effectively.

Lakatos viewed scientific progress as developing within research programs having two main components. The hard core, for Lakatos, was the set of central assumptions that define the program, which are not easily abandoned. The protective belt is a flexible layer of auxiliary hypotheses, methods, and data interpretations that can be adjusted to defend the hard core from anomalies. A research program is progressive if it predicts novel phenomena and those predictions are confirmed empirically. It is degenerating if its predictions fail and it relies on ad hoc modifications to explain away anomalies.

In climate science, the hard core would be that global climate is changing, that greenhouse gas emissions drive this change, and that climate models can reliably predict future trends. Its protective belt would be the evolving methods of collecting, revising, and interpreting weather data adjustments due to new evidence such as volcanic activity.

Lakatos would be more lenient than Popper about continual theory revision and model-tweaking on the grounds that a progressive research agenda’s revision of its protective belt is justified by the complexity of the topic. Signs of potential degeneration of the program would include the “pause” in warming from 1998–2012, explained ad hoc as natural variability, particularly since natural variability was invoked too early to know whether the pause would continue. I.e., it was called a pause with no knowledge of whether the pause would end.

I suspect Lakatos would be on the fence about climate science, seeing it as more progressive (in his terms, not political ones) than rival programs, but would be concerned about its level of dogmatism.

Paul Feyerabend: Tyranny of Methodological Monism

Kuhn, Lakatos, and Paul Feyerabend were close friends who, while drawing on each other’s work, differed greatly in viewpoint. Feyerabend advocated epistemological anarchism, defending his claim that no scientific advancement ever proceeds purely within what is taught as “the scientific method.” He argued that science should be open to diverse approaches and that imposing methodological rules suppresses necessary creativity and innovation. Feyerabend often cited Galileo’s methodology, which bears little in common with what is called the scientific method. He famously claimed that anything goes in science, emphasizing the importance of methodological pluralism.

From Feyerabend’s perspective, climate science excessively relies on a narrow set of methodologies, particularly computer modeling and statistical analysis. The field’s heavy dependence on these tools and its discounting of historical climatology is a form of methodological monism. Its emphasis on consensus, rigid practices, and public hostility to dissent (more on below) would be viewed as stifling the kind of creative, unorthodox thinking that Feyerabend believed essential for scientific breakthroughs. The pressure to conform coupled with the politicization of climate science has led to a homogenized field that lacks cognitive diversity.

Feyerabend distrusted the orthodoxy of the social practices in what Kuhn termed “normal science” – what scientific institutions do in their laboratories. Against Lakatos, Feyerabend distrusted any rule-based scientific method at all. Science in the mid 1900’s had fallen prey to the “tyranny of tightly knit, highly corroborated, and gracelessly presented theoretical systems.”

Viewing science as an institution, he said that science was a threat to democracy and that there must be “a separation of state and science just as there is a separation between state and religious institutions.” He called 20th century science “the most aggressive, and most dogmatic religious institution.” He wrote that institutional science resembled more the church of Galileo’s day than it resembled Galileo. I think he would say the same of climate science.

Feyerabend complained that university research requires “a willingness to subordinate one’s ideas to those of a team leader.” In the case of global warming, government and government-funded scientists are deciding not only what is important as a scientific program but what is important as energy policy and social agenda. Feyerabend would be utterly horrified.

Feyerabend’s biggest concern, I suspect, would be the frequent alignment of climate scientists with alternative energy initiatives. Climate scientists who advocate for solar, wind, and hydrogen step beyond their expertise in diagnosing climate change into prescribing solutions, a policy domain involving engineering and economics. Michael Mann still prioritizes “100% renewable energy,” despite all evidence of its engineering and economical infeasibility.

Further, advocacy for a specific solution over others (nuclear power is often still shunned) suggests a theoretical precommitment likely to introduce observational bias. Climate research grants from renewable energy advocates including NGOs the Department of Energy’s ARPA-E program create incentives for scientists to emphasize climate problems that those technologies could cure. Climate science has been a gravy train for bogus green tech, such as Solyndra and Abound Solar.

Why Not Naomi Oreskes?

All my science history gods are dead white men. Why not include a prominent living historian? Naomi Oreskes at Harvard is the obvious choice. We need not speculate about how she would view climate science. She has been happy to tell us. Her activism and writings suggest she functions more as an advocate for the climate political cause than a historian of science. Her role extends past documenting the past to shaping contemporary debate.

Oreskes testified before U.S. congressional committees (House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis, 2019, and the Senate Budget Committee, 2023), as a Democratic-invited witness. There she accused political figures of harassing scientists and pushed for action against fossil fuel companies. She aligns with progressive anti-nuclear leanings. An objective historian would limit herself to historical facts and the resulting predictions and explanations rather than advocating specific legislative actions. She embraces the term “climate activist,” arguing that citizen engagement is essential for democracy.

Oreskes’s scholarship, notably her 2004 “The Scientific Consensus on Climate Change” and her book Merchants of Doubt, employ the narrative of universal scientific agreement on anthropogenic climate change while portraying dissent solely as industry-driven disinformation. She wrote that 100% of 928 peer-reviewed papers supported the IPCC’s position on climate change. Conflicting peer-reviewed papers show Oreskes to have, at best, cherry-picked data to bolster a political point. Pursuing legal attacks on fossil fuel companies is activism, not analysis.

Acts of the “Relevant Community”

Countless scientists themselves engage in climate advocacy, even in the analysis of effectiveness of advocacy. Advocacy backed by science, and science applied to advocacy. A paradigmatic example – using Kuhn’s term literally – is Dr. James Lawrence Powell’s 2017 “The Consensus on Anthropogenic Global Warming Matters.” In it, Powell addresses a critic’s response to Powell’s earlier report on the degree of scientific consensus. Powell argues that 99.99% of scientists accept anthropogenic warming, rather than 97% as his critic claims. But the thrust of Powell’s paper is that the degree of consensus matters greatly, “because scholars have shown that the stronger the public believe the consensus to be, the more they support the action on global warming that human society so desperately needs.” Powell goes on for seven fine-print pages, citing Oreskes’ work, with charts and appendices on the degree of scientific consensus. He not only focuses on consensus, he seeks consensus about consensus.

Of particular interest to anyone with Kuhn’s perspective – let alone Feyerabend’s – is the way climate science treats its backsliders. Dissenters are damned from the start, but those who have left the institution (literally, in the case of The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) are further vilified.

Dr. Richard Tol, lead author for the Fifth IPCC Assessment Report, later identified methodological flaws in IPCC work. Dr. Judith Curry, lead author for the Third Assessment Report, later became a prominent critic of the IPCC’s consensus-driven process. She criticized climate models and the IPCC’s dismissal of natural climate variability. She believes (in Kuhnian terms) that the IPCC’s theories are value-laden and that their observations are theory-laden, the theory being human causation. Scientific American, a once agenda-less publication, called Curry a “climate heretic.” Dr. Patrick Michaels, contributor to the Second Assessment Report later emerged as a vocal climate change skeptic, arguing that the IPCC ignores natural climate variability and uses a poor representation of climate dynamics.

These scientists represent a small minority of the relevant community. But that community has challenged the motives and credentials of Tol, Curry, and Michaels more than their science. Michael Mann accused Curry of undermining science with “confusionism and denialism” in a 2017 congressional testimony. Mann said that any past legitimate work by Curry was invalidated by her “boilerplate denial drivel.” Mann said her exit strengthened the field by removing a disruptive voice. Indeed.

Tampering with Evidence

Everything above deals with methodological and social issues in climate science. Kuhn, Feyerabend, and even the Strong Program sociologists of science, assumed that scientists were above fudging the data. Tony Heller, Harvard emeritus professor of Geophysics, has, for over a decade, assembled screenshots of NASA and NOAA temperature records that prove continual revision of historic data, making the past look colder and the present look hotter. Heller’s opponents relentlessly engage in ad hominem attacks and character-based dismissals, rather than focusing on the substance of his arguments. If I can pick substance from his opponents’ positions, it would be that Heller cherry-picks U.S.-only examples and dismisses global evidence and corroboration of climate theory by evidence beyond temperature data. Heller may be guilty of cherry-picking. I haven’t followed the debate closely for many years.

But in 2013, I wrote to Judith Curry on the topic, assuming she was close to the issue. I asked her what fraction of NASA’s adjustments were consistent with strengthening the argument for 20th-century global warming, i.e., what fraction was consistent with Heller’s argument. She said the vast majority of it was.

Curry acknowledged that adjustments like those for urban heat-island effects and differences in observation times are justified in principle, but she challenged their implementation. In a 2016 interview with The Spectator, she said, “The temperature record has been adjusted in ways that make the past look cooler and the present warmer – it’s not a conspiracy, but it’s not neutral either.” She ties the bias to institutional pressures like funding and peer expectations. Feyerabend would smirk and remark that a conspiracy is not needed when the paradigm is ideologically aligned from the start.

In a 2017 testimony before the U.S. House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology, Curry said, “Adjustments to historical temperature data have been substantial, and in many cases, these adjustments enhance the warming trend.” She cited this as evidence of bias, implying the process lacks transparency and independent validation.

Conclusion

From the historical and philosophical perspectives discussed above, climate science can be critiqued as bad science. For the Logical Positivists, its global, far-future claims are hard to verify directly, challenging their empirical basis. For Hempel, its reliance on models and statistical trends rather than universal laws undermines its deductive explanatory power. For Popper, its long-term predictions resist falsification, blurring the line between science and non-science. For Kuhn, its dominant paradigm suppresses alternative viewpoints, hindering progress. Lakatos would likely endorse its progressive program, but would challenge its dogmatism. Feyerabend would be disgusted by its narrow methodology and its institutional rigidness. He would call it a religion – a bad one. He would quip that 97% of climate scientists agree that they do not want to be defunded. Naomi Oreskes thinks climate science is vital. I think it’s crap.

Fuck Trump: The Road to Retarded Representation

Posted by Bill Storage in History of Science on April 2, 2025

-Bill Storage, Apr 2, 2025

On February 11, 2025, the American Federation of Government Employees (AFGE) staged a “Rally to Save the Civil Service” at the U.S. Capitol. The event aimed to protest proposed budget cuts and personnel changes affecting federal agencies under the Trump administration. Notable attendees included Senators Brian Schatz (D-HI) and Chris Van Hollen (D-MD), and Representatives Donald Norcross (D-NJ) and Maxine Dexter (D-OR).

Dexter took the mic and said that “we have to fuck Trump.” Later Norcross led a “Fuck Trump” chant. The senators and representatives then joined a song with the refrain, “We want Trump in jail.” “Fuck Donald Trump and Elon Musk,” added Rep. Mark Pocan (D-WI).

This sort of locution might be seen as a paradigmatic example of free speech and authenticity in a moment of candid frustration, devised to align the representatives with a community that is highly critical of Trump. On this view, “Fuck Trump” should be understood within the context of political discourse and rhetorical appeal to a specific audience’s emotions and cultural values.

It might also be seen as a sad reflection of how low the Democratic Party has sunk and how low the intellectual bar has dropped to become a representative in the US congress.

I mostly write here about the history of science, more precisely, about History of Science, the academic field focused on the development of scientific knowledge and the ways that scientific ideas, theories, and discoveries have evolved over time. And how they shape and are shaped by cultural, social, political, and philosophical contexts. I held a Visiting Scholar appointment in the field at UC Berkeley for a few years.

The Department of the History of Science at UC Berkeley was created in 1960. There in 1961, Thomas Kuhn (1922 – 1996) completed the draft of The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, which very unexpectedly became the most cited academic book of the 20th century. I was fortunate to have second-hand access to Kuhn through an 18-year association with John Heilbron (1924 – 2023), who, outside of family, was by far the greatest influence on what I spend my time thinking about. John, Vice-Chancellor Emeritus of the UC System and senior research fellow at Oxford, was Kuhn’s grad student and researcher while Kuhn was writing Structure.

I want to discuss here the uncannily direct ties between Thomas Kuhn’s analysis of scientific revolutions and Rep. Norcross’s chanting “Fuck Trump,” along with two related aspects of the Kuhnian aftermath. The second is academic precedents that might be seen as giving justification to Norcross’s pronouncements. Third is the decline in academic standards over the time since Kuhn was first understood to be a validation of cultural relativism. To make this case, I need to explain why Thomas Kuhn became such a big deal, what relativism means in this context, and what Kuhn had to do with relativism.

To do that I need to use the term epistemology. I can’t do without it. Epistemology deals with questions that were more at home with the ancient Greeks than with modern folk. What counts as knowledge? How do we come to know things? What can be known for certain? What counts as evidence? What do we mean by probable? Where does knowledge come from, and what justifies it?

These questions are key to History of Science because science claims to have special epistemic status. Scientists and most historians of science, including Thomas Kuhn, believe that most science deserves that status.